Chichester Canal

| Chichester Canal | |

|---|---|

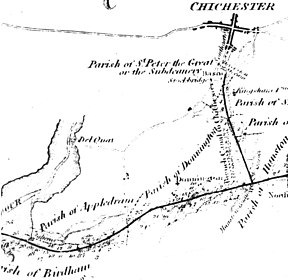

A map of the planned route of the canal from 1815 | |

| |

| Specifications | |

| Maximum boat length | 85 ft 0 in (25.91 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 18 ft 0 in (5.49 m) |

| Locks | 2 |

| Status | part navigable |

| Navigation authority | West Sussex County Council |

| History | |

| Date of act | 1819 |

| Date of first use | 1822 |

| Date closed | 1928 |

| Date restored | 1984 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Chichester |

| End point | Chichester Harbour |

The Chichester Canal is a ship canal in England, currently navigable at either end, save for two low-level modern bridges obstructing the middle of the route. Its course is essentially intact, 3.8 miles (6.1 km) from the sea at Birdham on Chichester Harbour to Chichester through two locks. The canal (originally part of the Portsmouth and Arundel Canal) was opened in 1822 and took three years to build. The canal could take ships of up to 100 long tons (100 t). Dimensions were limited to 85 feet (26 metres) long, 18 feet (5.5 m) wide and a draft of up to 7 feet (2.1 m).[1] As denoted by the suffix -chester, Chichester is a Roman settlement (Noviomagus Reginorum), and 300 Denarii were unearthed when Chichester Basin was formed in the 1820s.

History

Planning, construction and early operation

Chichester Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Proposals for a canal linking Chichester directly to the sea go back as least as far as 1585 when an act of parliament was passed allowing a cut linking Chichester with the sea.[2] Further proposals were made in the early 19th century, with schemes being proposed in 1801, 1802, 1803 and 1811, but none of these came to pass and as a result the first link to the sea was via a branch of the Portsmouth and Arundel Canal opened in 1822.[2] In 1817 it had been decided that the section between Chichester and Chichester Harbour, unlike the rest of the canal, would be built large enough to carry boats of 100 tons.[2] Putting this into practice required a new act of parliament which was obtained in 1819.[3] In the same year the construction of the Chichester branch began.[4] In digging out of the basin a hoard of 300 Denarii was found.[5] The section of the canal that would become the Chichester Canal was formally opened on 9 April 1822[6]

The Portsmouth and Arundel Canal was conceived as part of a bigger plan to provide a secure inland canal route from London to Portsmouth, but by the time the route was completed, the war with France had ended. With the reason for its construction removed, the canal was not a commercial success, and apart from the Chichester section, it had fallen into disuse by 1847.[7]

Under the ownership of the Corporation of Chichester

The canal was transferred to the Corporation of Chichester in 1892.[8] In November of that year the City Surveyor gave a figure of £1000 to put the canal back into full working order; key tasks were repair of locks, bridges and the removal of weeds and mud from the channel.[9] By 1898 only 704 tons of goods were carried – tolls for the year were £18.[10] The last recorded commercial traffic was in 1906 when a load of shingle was carried from the Harbour to the basin.[11] In the same year it was found that the swing bridge at Donnington and Birdham needed to be repaired or replaced. Westhampnett Rural District Council wanted to replace them with fixed bridges (which would have blocked the canal) but the Corporation of Chichester wanted to keep the canal open to traffic. By 1923 the Corporation appears to have accepted that there would be no further great loads; it authorised and funded fixed bridges.[9]

The canal was officially open for trade until June 1928 before being formally abandoned.[11]

In 1932 the section of the canal between Cutfield Bridge and Salterns lock was reopened to allow yachts to be berthed there.[12] The open section was initially leased by D.S. Vernon but in 1934 he transferred it to the Chichester Yacht Company.[13]

World War II

In Britain in World War II the canal towpath was made an anti-tank and anti-barge route by the 4th Infantry Division (United Kingdom) to militate against a German invasion. This entailed dismantling 4 swing bridges, diversion of some of the Lavant to raise the water by 3 feet (0.91 m) (thus over the towpath) and a low dam above Cutfield bridge.[14][13] The partial diversion proved hard to control and the fluctuations damaged the canal and a houseboat;[13] argument as to the duty to compensate lasted until June 1947.[15]

Post war

In 1953 the canal and surrounding lands were sold to West Sussex County Council for £7,500.[16] The council let plans be known to use part of the canal for road improvement, on opposition and with higher priority issues for funds, these never took place.[16] The section below Cutfield Bridge continued to be leased to the Chichester Yacht Company while the upper part of the canal was leased to Chichester Canal Angling Association.[16]

In January 1994 floodwaters in lower Chichester were diverted into the canal.[17]

A 2009 restoration of Casher's Lock was halted due to the presence of water voles.[18] This is not necessarily an insurmountable obstacle; see ecology work on the Stroudwater Navigation, where in partnership with Gloucestershire Wildlife Trust, new wetland habitats alongside canal construction are helping to extend the range of endangered species.

As of 2021 the sea lock is no longer in working order and is beginning to collapse at the harbour end.[needs update][citation needed]

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chichester Basin | 50°49′49″N 0°46′54″W / 50.8304°N 0.7817°W | SU859041 | |

| Junction with disused Portsmouth and Arundel Canal | 50°48′47″N 0°46′29″W / 50.8131°N 0.7746°W | SU864022 | |

| Site of Casher Lock | 50°48′12″N 0°48′45″W / 50.8033°N 0.8126°W | SU837010 | |

| Salterns Lock | 50°48′14″N 0°49′41″W / 50.8040°N 0.8281°W | SU826011 | Chichester Channel |

See also

Bibliography

- Green, Alan H.J. (2006). The History of Chichester's Canal. Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society. ISBN 978-0-9512036-1-3.

- Hadfield, Charles (1969). The Canals of South and South East England. David and Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-4693-8.

- Heneghan, F. D. (1958). The Chichester Canal. Chichester City Council. ASIN B000XCT5Z6.

- Vine, P.A.L (1985). West Sussex waterways. Middleton Press. ISBN 978-0-906520-24-6.

- Vine, P.A.L (2005). London's Lost Route to Portsmouth. Phillimore & Co. ISBN 978-1-86077-283-2.

References

- ^ Heneghan 1958, p. 15

- ^ a b c Heneghan 1958, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 24.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 26.

- ^ Green 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Vine 1985

- ^ Vine 2005, p. 153.

- ^ a b Heneghan 1958, p. 19.

- ^ Vine 2005, p. 155.

- ^ a b Vine 2005, p. 161.

- ^ Hadfield 1969, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Green 2006, p. 65

- ^ Vine 2005, p. 163

- ^ Green 2006, pp. 65–70

- ^ a b c Green 2006, pp. 73–74

- ^ Chaudhary, Vivek (11 January 1994). "Sales boom helps trader overcome that sinking feeling". The Guardian. Manchester.

- ^ "Voles Halt Chichester Restoration". Waterways (226): 32. Winter 2009.

External links

![]() Media related to Chichester Canal at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chichester Canal at Wikimedia Commons