Iyad ibn Ghanm

ʿIyāḍ ibn Ghanm ibn Zuhayr al-Fihrī | |

|---|---|

| Born | Mecca, Hejaz, Arabia |

| Died | c. 641 CE Hims, Syria |

| Allegiance | Rashidun Caliphate (632–641) |

| Service | Rashidun army |

| Battles / wars |

|

| Relations | |

| Other work |

|

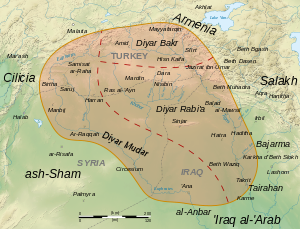

ʿIyāḍ ibn Ghanm ibn Zuhayr al-Fihrī (Template:Lang-ar) (died 641), was an Arab general who played a leading role in the Muslim conquests of al-Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) and northern Syria. He was among the handful of Qurayshi tribesmen to embrace Islam before the mass conversion of the tribe in 630, and was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In 634, under Caliph Abu Bakr, he governed the north Arabian oasis town of Dumat al-Jandal. Later, in 637, he became governor of al-Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia), but was dismissed by Caliph Umar (r. 634–644) for alleged improprieties. Afterward, he became a close military aide of his cousin and nephew, Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, under whose direction Iyad conquered much of Byzantine-held northern Syria, including Aleppo, Manbij and Cyrrhus.

When Abu Ubayda died in 639, Iyad succeeded him as governor of Hims, Qinnasrin and al-Jazira. In the latter territory, he launched a campaign to assert Muslim rule, first capturing Raqqa after conquering the countryside. This was followed by the conquests of Edessa, Harran and Samosata under similar circumstances. With the exception of heavy fighting at Ras al-Ayn and Dara, Iyad received the surrenders of a string of other Mesopotamian towns with relatively little blood spilled. Overall, Iyad's conquest of Upper Mesopotamia left much of the captured towns intact and their inhabitants unharmed to maintain their tax payments to the nascent caliphate. According to historian Leif Inge Ree Petersen, Iyad "has received little attention" but was "clearly of great ability".

Early life

Iyad was the son of a certain 'Abd Ghanm ibn Zuhayr al-Fihri. He belonged to the al-Harith ibn Fihr ibn Malik branch of the Quraysh tribe.[1][2] The latter were a mercantile Arab tribe based in Mecca in the western Arabian Peninsula.[3] Iyad was among the few members of the Quraysh to have embraced Islam prior to the truce at Hudaybiyya between the Islamic prophet Muhammad and the largely pagan Quraysh in 628, and was present alongside Muhammad during the peace negotiations.[4] Upon accepting Islam, Iyad had his name changed from "ibn ʿAbd Ghanm" to "ibn Ghanm"; "ʿAbd Ghanm", the name of his father, translates in Arabic as "servant of Ghanm", an idol worshiped by the pagan Arabs.[5] The latter was an association that Iyad detested, according to 9th-century historian al-Baladhuri.[5] The rest of the Quraysh converted to Islam in 630.[6]

Campaigns in Syria

Iyad may have been the Muslim commander who defeated an Arab tribal revolt in the oasis town of Dumat al-Jandal during the Ridda wars of 632–633.[7][8] The tribes involved in the revolt were the Banu Kalb, Banu Salīh, Tanukh and Ghassan.[8] Other medieval reports attribute this victory to 'Amr ibn al-'As.[7] In any case, according to 9th-century historian al-Tabari, Iyad was governor of Dumat al-Jandal in 634, during the reign of Caliph Abu Bakr.[7] In 637, Iyad was made governor of al-Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) by Caliph Umar (r. 634–644),[9] but was dismissed by the latter due to allegations that he had used his office to accept gifts or bribes.[10] Afterward, he became a close aide and lieutenant commander of his paternal cousin and maternal nephew, Abu Ubayda ibn al-Jarrah, who had military authority over Syria.[10][11]

In 638, Iyad was dispatched by Abu Ubayda to subdue Aleppo (Beroea) in northern Syria, then part of the Byzantine Empire.[5] Abu Ubayda himself arrived later, but as soon as he set up camp around the city, the townspeople signaled their desire to negotiate terms.[5] Iyad, who was sanctioned by Abu Ubayda to negotiate on his behalf, agreed to the proposed terms guaranteeing the safety of Aleppo's inhabitants and properties, but with the condition that a site be made available for the construction of a mosque.[5] Abu Ubayda later sent Iyad at the head of an army to capture Cyrrhus, whose inhabitants sent out a monk to meet Iyad; following this meeting, Iyad had the monk meet Abu Ubayda and arrange the surrender of Cyrrhus.[12] Iyad continued on northward and eastward, overseeing the capitulation of Manbij (Hierapolis), Ra'ban and Duluk.[13]

Conquest of Upper Mesopotamia

As response of the siege toward Emesa by Byzantine and Christian Arabs coalition in around 638, Iyad was tasked by caliph Umar through his superior, Abu Ubaydah to invade Al-Jazira.m[14][15][16]

When Abu Ubayda died in 639, Caliph Umar appointed Iyad in his place as the ʿamal (governor) of Hims, Qinnasrin (Chalcis) and al-Jazira with directions to conquer the latter territory from its Byzantine commanders because they had refused to pay the tributes promised to the Muslims in 638.[17][18][19] By the time Iyad was given his assignment, all of Syria had been conquered by the Muslims, leaving the Byzantine garrisons in al-Jazira isolated from the empire.[20] In August 639, Iyad led a 5,000-strong army toward Raqqa (Kallinikos) in al-Jazira and raided the city's environs.[17] He encountered resistance from its defenders,[17] prompting him to withdraw and send smaller units to make raids around Raqqa, seizing captives and harvests.[21] After five or six days of these raids, Raqqa's patrician negotiated the surrender of the city to Iyad.[21] According to historian Michael Meinecke, Iyad captured the city in 639 or 640.[22]

After Raqqa, Iyad proceeded toward Harran, where his progress was stalled. He diverted part of his army to Edessa, which ultimately capitulated after negotiations.[23] Iyad then received Harran's surrender and dispatched Safwan ibn Mu'attal al-Sulami and his own kinsman Habib ibn Maslama al-Fihri to seize Samosata, which also ended in a negotiated surrender after Muslim raiding of its countryside.[24][25] By 640, Iyad had successively conquered Saruj, Jisr Manbij and Tell Mawzin.[26] Before the capture of Tell Mawzin, Iyad attempted to take Ras al-Ayn, but retreated after stiff resistance.[26][27] Later, he dispatched Umayr ibn Sa'd al-Ansari to take the city.[28][29] Umayr first assaulted the rural peasantry and seized cattle in the town's vicinity.[28] The inhabitants barricaded inside the walled city and inflicted heavy losses on the Muslim forces, before ultimately capitulating.[28] About the same time, Iyad besieged Samosata in response to a rebellion, the nature of which is not specified by al-Baladhuri,[30] and stationed a small garrison in Edessa after the city's inhabitants violated their terms of surrender.[26]

After Samosata, al-Baladhuri, who gives a detailed but triumphalist account of the Mesopotamian campaign, maintains that Iyad subdued a string of villages "on the same terms" as Edessa's surrender.[27] Between the end of 639 and December 640, Iyad and his lieutenants subdued, in succession, Circesium (al-Qarqisiya), Amid, Mayyafariqin, Nisibin, Tur Abdin, Mardin, Dara, Qarda and Bazabda.[31] According to al-Baladhuri, with the exception of Nisibin, which put up resistance, all these cities and fortresses fell to the Muslims after negotiated surrenders.[31] In contrast to al-Baladhuri's passive account of Iyad's capture of Dara, 10th-century historian Agapius of Hierapolis wrote that many were slain on both sides, particularly among the Muslims, but the city ultimately fell after a negotiated surrender.[27] Iyad continued toward Arzanene, then to Bitlis and finally to Khilat; all three cities surrendered after negotiations with their patricians.[31] Shortly after, Iyad entrusted the leader of Bitlis with collecting the land tax from Khilat, and left for Raqqa.[31] On the way there, one medieval Muslim report holds that Iyad dispatched a force to capture Sinjar, after which he settled it with Arabs.[32]

Iyad died in Hims in 641.[31] According to al-Tabari, Iyad was succeeded as governor of Hims and Qinnasrin by a certain Sa'id ibn Hidhyam al-Jumahi, but the latter died soon after and Umayr ibn Sa'd, one of Iyad's lieutenants, was appointed in his place by Caliph Umar.[33]

Assessment

According to 9th-century biographer Ibn Sa'd, "not a foot was left of Mesopotamia unsubdued by Iyad ibn Ghanm", and Iyad "effected the conquest of Mesopotamia and its towns by capitulation, but its land by force".[34] Petersen describes Iyad as "a commander who has received little attention, but who clearly was of great ability".[19] The tactics used by Iyad in his Mesopotamian campaign were similar to those employed by the Muslims in Palestine, though in Iyad's case the contemporary accounts reveal his specific modus operandi, particularly in Raqqa.[30] The operation to capture that city entailed positioning cavalry forces near its entrances, preventing its defenders and residents from leaving or rural refugees from entering.[30] Concurrently, the remainder of Iyad's forces cleared the surrounding countryside of supplies and took captives.[30] These dual tactics were employed in several other cities in al-Jazira.[30] They proved effective in gaining surrenders from targeted cities running low on supplies and whose satellite villages were trapped by hostile troops.[30] Iyad's overall goal was to conquer al-Jazira with minimal damage to ensure the flow of revenue to the caliphate.[30] In the agreements he reached with the patricians of Raqqa, Edessa, Harran and Samosata, payments came in various forms, including cash, wheat, oil, vinegar, honey, labor services to maintain roads and bridges, and guides and intelligence for the Muslim newcomers.[30]

Ultimately, Iyad's settlements with Mesopotamia's cities "to a large extent left most of local society untouched".[35] In the view of Petersen, Iyad's campaign partially diverted the Byzantines' attention away from the Muslims' central offensive against Syria's port cities and the province of Egypt, while also "demonstrating to the Armenian nobility that the Caliphate had become a viable alternative to the Persian Empire".[36]

References

- ^ Ibn 'Abd Rabbih 2011, p. 233.

- ^ Theophilus of Edessa 2011, p. 118, n. 271.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 51.

- ^ Muhammad ibn Sa'd 1997, p. 247.

- ^ a b c d e Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 226.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 77.

- ^ a b c Vaglieri 1965, p. 625.

- ^ a b Shahid 1989, p. 304.

- ^ Juynboll 1989, pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b Humphreys 1990, p. 72.

- ^ Juynboll 1989, p. 80.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 230.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 231.

- ^ Ibrahim Akram, Agha; Ibn Kathir, Abu al-Fiḍā ‘Imād Ad-Din Ismā‘īl (October 18, 2017). The Sword of Allah Khalid Bin Al-Waleed, His Life and Campaigns. American Eagle Animal Rescue. p. 310. ISBN 9781948117272. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ El Hareir, Idris; Mbaye, Ravane (2011). The Spread of Islam Throughout the World. UNESCO Pub. p. 949. ISBN 9789231041532. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Donner, Fred (July 14, 2014). The Early Islamic Conquests (electronic ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 512. ISBN 9781400847877. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 270.

- ^ Friedmann 1992, p. 134 n. 452.

- ^ a b Petersen 2013, p. 434.

- ^ Canard 1965, p. 574.

- ^ a b Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 271.

- ^ Meinecke 1995, p. 410.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 272.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 273.

- ^ Haase 1997, p. 871.

- ^ a b c Al-Baladhuri 1916, pp. 274–275.

- ^ a b c Petersen 2013, p. 436.

- ^ a b c Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 276.

- ^ Honigmann 1995, p. 433.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Petersen 2013, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d e Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 275.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 277.

- ^ Humphreys 1990, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Al-Baladhuri 1916, p. 273–274.

- ^ Petersen 2013, pp. 437–438.

- ^ Petersen 2013, p. 439.

Bibliography

- Al-Baladhuri (1916). Hitti, Philip Khuri (ed.). The Origins of the Islamic State, Volume 1. London: Columbia University, Longmans, Green & Co. OCLC 622246259.

- Canard, M. (1965). "Al-Djazīra". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 523–524. OCLC 495469475.OCLC 192262392

- Ibn 'Abd Rabbih (2011). Boullata, Emeritus Issa J. (ed.). The Unique Necklace, Volume III. Reading: Garnet Publishing Limited & Southern Court. ISBN 978-1-85964-240-5.

- Donner, Fred M. (1981). The Early Islamic Conquests. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4787-7.

- Haase, C. P. (1997). "Sumaysāṭ". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume IX: San–Sze. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 871–872. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Honigmann, M. (1995). "Raʾs al-ʿAyn". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 433–435. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Meinecke, M. (1995). "Al-Rakka". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume VIII: Ned–Sam. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 410–414. ISBN 978-90-04-09834-3.

- Muhammad ibn Sa'd (1997). Bewley, Aisha (ed.). The Men of Madina, Volume 1. London: Ta-Ha Publishers. ISBN 978-1-897940-68-6.

- Petersen, Leif Inge Ree (2013). Siege Warfare and Military Organization in the Successor States (400-800 AD): Byzantium, the West and Islam. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-25199-1.

- Shahid, Irfan (1989). Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fifth Century. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Trustees for Harvard University. ISBN 978-0-88402-152-0.

- Juynboll, Gautier H.A., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XIII: The Conquest of Iraq, Southwestern Persia, and Egypt: The Middle Years of ʿUmar's Caliphate, A.D. 636–642/A.H. 15–21. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-876-8.

- Humphreys, R. Stephen, ed. (1990). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XV: The Crisis of the Early Caliphate: The Reign of ʿUthmān, A.D. 644–656/A.H. 24–35. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0154-5.

- Friedmann, Yohanan, ed. (1992). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XII: The Battle of al-Qādisīyyah and the Conquest of Syria and Palestine. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0733-2.

- Theophilus of Edessa (2011). Hoyland, Robert G. (ed.). Theophilus of Edessa's Chronicle and the Circulation of Historical Knowledge in Late Antiquity and Early Islam. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-697-5.

- Vaglieri, L. Veccia (1965). "Dūmat al-Djandal". In Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Volume II: C–G. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 624–626. OCLC 495469475.