Ranabir Singh Thapa

Ranabir Singh Thapa | |

|---|---|

| श्री जनरल काजी रणवीर सिंह थापा | |

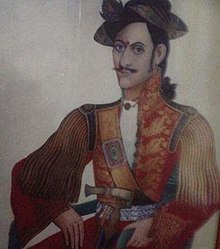

Ranabir Singh Thapa c. 1830 | |

| Acting Mukhtiyar (Acting PM) of Nepal[1] | |

| Preceded by | Bhimsen Thapa |

| Succeeded by | Bhimsen Thapa |

| Personal details | |

| Relations | see Thapa dynasty |

| Parents |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | Kalibaksh Battalion, Shree Sabuj Battalion |

| Battles/wars | Anglo-Nepalese war |

Ranabir Singh Thapa (Template:Lang-ne) also spelled Ranbir, Ranavir or Ranvir also known by the late ascetic name Swami Abhayananda (Template:Lang-ne) was a Nepalese Army General, prominent politician and minister of state. In 1837, he became Acting Mukhtiyar (equivalent to Prime Minister) of Nepal for a brief period. He was a prominent member of Thapa dynasty. He later turned ascetic and was known by the Sanyasi name Swami Abhayananda.

Early life

Ranabir Singh was born as the youngest son of Sanukaji Amar Singh Thapa and Satyarupa Maya.[2] He was the brother of Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa.[3]

Life as politician and military officer

He was the Commander of the Makwanpur-Hariharpur axis during Anglo-Nepalese war.[4] In 1871 BS (1814 AD) he was deputed to Makwanpur to command the troops. He was leading 4000 soldiers against Major General Marley and Major General Woods. They were lured to major killing area by Ranabir Singh but Major-General Woods did not advance from Bara Gadhi. [4] After the war he became the administrator of Palpa and the general of Kalibash and Sabuj battalion.

He was appointed chief member at the Royal Palace to keep observation on the King and Queen.[6][5] After the death of Queen Tripurasundari of Nepal, the royal seal by which government orders were approved naturally went into the hands of the senior queen Samrajya Lakshmi Devi, who knew all too well of its powers and wanted to emulate the queens of the past by establishing her own regency.[7][8] Sensing Samrajya Laxmi's ambition, Ranbir Singh started to stroke her dislike of Bhimsen in the hopes of becoming the Mukhtiyar himself.[7] There was a quarrel between Mathabar Singh Thapa and Ranabir Singh regarding the latter's loyalty shift towards the senior Queen Samrajya Lakshmi resulting in Mathabar resigning from the commandership of Sri Nath Regiment.[9] Getting a whiff of this matter, Bhimsen strongly reprimanded Ranbir Singh which caused him to resign from his General's position and live in retirement in his house at Sipamandan.[10] However, Bhimsen later managed to placate his brother, by giving him the title of Chota (Little) General, and send him to Palpa as its governor.[11][12] King Rajendra supported Bhimsen instead of Ranabir Singh and the removal of Ranabir Singh sabotaged the Queen's plan.[12]

In April 1835, Bhimsen also hatched a plan to make a state visit to Great Britain, hoping to secure recognition of the sovereignty of Nepal; but since he could not make the visit himself, his nephew Colonel Mathabar Singh Thapa was chosen as the representative of Nepal, bearing a few gifts and a letter from King Rajendra addressed to King William IV.[13][14][15] In this process, Ranbir Singh, the governor of Palpa, was made Full General beside the promotion of Mathabar Singh Thapa and Sher Jung Thapa.[15] After the annual muster at the beginning of 1837, an investigation was also started to check Bhimsen's expenditures in establishing various battalions.[16] Such events led the courtiers to feel that Bhimsen's Mukhtiyari would not last very long; thus Ranbir Singh Thapa, in the hopes of becoming the next Mukhtiyar, wrote a letter to the King asking him to be recalled to Kathmandu from Palpa. His wish was granted; and Bhimsen, pleased to see his brother after many years, made Ranbir Singh the acting Mukhtiyar and decided to go to his ancestral home in Borlang Gorkha for the sake of pilgrimage.[1] On 24 July 1837, Rajendra's youngest son, Devendra Bikram Shah, an infant of six months, died suddenly.[17][18] It was at once rumored that the child had died of poison intended for his mother the Senior Queen Samrajya Laxmi Devi: given at the instigation of Bhimsen, or someone of his party.[18][19][20] On this charge, Bhimsen, his brother Ranbir Singh, his nephew Mathbar Singh, their families, the court physicians, Ekdev and Eksurya Upadhyay, and his deputy Bhajuman Baidya, with a few more of the nearest relatives of the Thapas were incarcerated, proclaimed outcasts, and their properties confiscated.[18][19][21][22]

Release and ascetic life

Fearful that the Pandes would re-establish their power, Fatte Jang Shah, Ranganath Poudel, and the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi Devi obtained from the King the liberation of Bhimsen, Mathabar, and the rest of the party, about eight months after they were incarcerated for the poisoning case.[23][24][25] Sensing that a catastrophe was going to befall the Thapas, Mathabar Singh fled to India while pretending to go on a hunting trip; Ranbir Singh gave up all his property and became a sanyasi, titling himself Abhayanand Puri; but Bhimsen Thapa preferred to remain in his old home in Gorkha.[25][26] He was rendered by the following full name in his ascetic life Shreemant Paramahamsa Paribrajakacharya Swami Abhayananda Giri Nepali.

Gallery

-

Ranabir Singh Thapa as Swami Abhayananda

References

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 157.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 23.

- ^ a b "Nepalese Army | नेपाली सेना". nepalarmy.mil.np. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ a b "Ranabir Singh Thapa".

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 148.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 149.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 147.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 151.

- ^ a b Pradhan 2012, p. 148.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Rana 1988, p. 18.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 158.

- ^ a b c Nepal 2007, p. 105.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 159.

- ^ Whelpton 2004, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Acharya 1971, p. 13.

- ^ Oldfield 1880, p. 310.

- ^ Oldfield 1880, p. 311.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 109.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 161.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 110.

Bibliography

- Acharya, Baburam (1971), "The Fall of Bhimsen Thapa and The Rise of Jang Bahadur Rana" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 3, Kathmandu: 214–219

- Acharya, Baburam (2012), Acharya, Shri Krishna (ed.), Janaral Bhimsen Thapa : Yinko Utthan Tatha Pattan (in Nepali), Kathmandu: Education Book House, p. 228, ISBN 9789937241748

- Nepal, Gyanmani (2007), Nepal ko Mahabharat (in Nepali) (3rd ed.), Kathmandu: Sajha, p. 314, ISBN 9789993325857

- Oldfield, Henry Ambrose (1880), Sketches from Nipal, Vol 1, vol. 1, London: W.H. Allan & Co.

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

- Rana, Rukmani (April–May 1988), "B.H. Hogson as a factor for the fall of Bhimsen Thapa" (PDF), Ancient Nepal (105), Kathmandu: 13–20, retrieved Jan 11, 2013

- Whelpton, John (2004), "The Political Role of Brian Hodgson", in Waterhouse, David (ed.), Origins of Himalayan Studies: Brian Houghton Hodgson in Nepal and Darjeeling, Royal Asiatic Society Books (1 ed.), Taylor & Francis, p. 320, ISBN 9781134383634