Hawkins County, Tennessee

Hawkins County | |

|---|---|

The Hawkins County Courthouse in Rogersville, built c. 1836, is the oldest courthouse in Tennessee | |

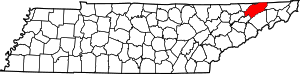

Location within the U.S. state of Tennessee | |

Tennessee's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 36°26′N 82°57′W / 36.44°N 82.95°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1787[1] |

| Named for | Benjamin Hawkins[2] |

| Seat | Rogersville |

| Largest city | Kingsport |

| Area | |

• Total | 500 sq mi (1,000 km2) |

| • Land | 487 sq mi (1,260 km2) |

| • Water | 13 sq mi (30 km2) 2.5% |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 56,721 |

| • Density | 117/sq mi (45/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional district | 1st |

| Website | www |

Hawkins County is a county located in the U.S. state of Tennessee. As of the 2020 census, the population was 56,721.[3] Its county seat is Rogersville,[4] Hawkins County is part of the Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is a component of the Johnson City-Kingsport-Bristol, TN-VA Combined Statistical Area, commonly known as the "Tri-Cities" region.

History

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2018) |

The land was given to William Armstrong as a land grant in the 1780s.[5] Armstrong built Stony Point.[5] Armstrong's landholding was established as a county in 1787.[1][6] It was named for Benjamin Hawkins, a U.S. Senator from North Carolina, the state which it was a part of at that time.[7] In 1797, Louis Philippe (who would become King of the French in 1830) visited Armstrong's estate.[5]

During the American Civil War, Hawkins County saw combat. The Battle of Rogersville took place on November 6, 1863.

Since the 1940s, a 1,900-2,200 acre area western Hawkins County was proposed and planned as state park known as Poor Valley State Park in order to promote economic development efforts in the upper East Tennessee region, the plan would stall in the 1970s.[8][9]

Law and government

Hawkins County is governed by a 21-member County Commission, whose members are elected from geographic districts. The chief executive officer of the county is the County Mayor.

Executive Branch

The Tennessee Constitution provides for the election of an executive officer – now referred to as the County Mayor – in each county. The County Mayor is elected by popular vote at the regular August election every four years, coinciding with the Governor's election, and may serve an unlimited number of terms. The County Mayor (formerly County Executive) is chief executive officer of the county. The County Mayor exercises a role of leadership in county government and is responsible for the county's fiscal management and other executive functions; however, the other principal officers of the county such as the Sheriff, Trustee, Assessor and most of the various Court Clerks are separately elected, responsible directly to the county's voters, and not under the direct supervision of the county mayor.

The County Mayor is the general agent of the county and may draw warrants upon the General Fund. The County Mayor has custody of county property not placed with other officers, and may also examine the accounts of county officers. The County Mayor is a nonvoting ex-officio member of the County Commission and of all its committees, and may be elected chairman of the county legislative body (a post that the County Mayor is not required to seek or accept). The County Mayor may call special meetings of the County Commission. Unless an optional general law or private act provides otherwise, the County Mayor compiles a budget for all county departments, offices, and agencies, which is presented to the County Commission.

The current Mayor of Hawkins County is Mark DeWitte (R-Rogersville).

Legislative Branch

Composition

The Hawkins County Board of Commissioners, also called the County Commission, is the legislative body of the County government and the primary policy-making body in the county. It consists of 21 elected members, three from each of the seven civil districts of Hawkins County. Each member serves a four-year term of office.

The County Commission operates with a committee structure; most Commission business is first considered by a committee of its members before coming to the full Commission. The County Clerk serves as the Secretary to the Board of Commissioners and is responsible for maintaining all official records of the meetings.

Powers and responsibilities

The most important function of the county legislative body is the annual adoption of a budget to allocate expenditures within the three major funds of county government - general, school, and highway - and any other funds (such as debt service) that may be in existence in that particular county. The county legislative body has considerable discretion in dealing with the budget for all funds except the school budget, which in most counties must be accepted or rejected as a whole. If rejected, the school board must continue to propose alternatives until a budget is adopted by both the county school board and the county legislative body.

The county legislative body sets a property tax rate which, along with revenues from other county taxes and fees as well as state and federal monies allocated to the county, are used to fund the budget. The county legislative body is subject to various restrictions in imposing most taxes (such as referendum approval or rate limits, for example), although these do not apply to the property tax. The University of Tennessee's County Technical Assistance Service (CTAS) publishes the County Revenue Manual to assist county officials in identifying sources of county revenue.

The county legislative body serves an important role in exercising local approval authority for private acts when the private act does not call for referendum approval. Private acts, which often give additional authority to counties, must be approved by a two-thirds vote of the members of the county legislative body or be approved by a referendum in order to become effective. The form of local approval required is specified in the private act. The county legislative body annually elects a chair and a chair pro tempore.

The county legislative body may elect the county executive or a member of the body to be the chair, although the county executive may refuse to serve. The county executive may veto most resolutions of the county legislative body, subject to a vote to override by a majority of the entire county legislative body. The county executive may break a tie vote while serving as chair of the county legislative body.

Another important function of the county legislative body is its role in electing county officers when there is a vacancy in an elected county office. The person elected by the county legislative body serves in the office for the remainder of the term or until a successor is elected, depending upon when the vacancy occurred. When filling a vacancy in a county office, the county legislative body must publish a notice in a newspaper of general circulation in the county at least one week prior to the meeting in which the vote will be taken. This notice must state the time, place and date of the meeting and the office to be filled. Also, members of the county legislative body must have at least ten days notice. The legislative body holds an open election to fill the vacancy and allows all citizens the privilege of offering as candidates.

Current members as of 2020:[10]

- District 1: Allandale, Kingsport, & Mount Carmel

- George Bridwell (Kingsport)

- Raymond Jessee (Mount Carmel])

- Syble Vaughan-Trent (Kingsport)

- District 2: Church Hill & McPheeter's Bend

- Fred Castle (McPheeter's Bend)

- Jeff Barrett (Church Hill)

- Keith Gibson (Church Hill)

- District 3: Carter's Valley, Wallace, & Watterson

- Danny Alvis (Surgoinsville)

- Charles Housewright (Church Hill)

- Charles Thacker (Surgoinsville)

- District 4: Dykes, Keplar, North Rogersville, Surgoinsville, & Upper Beech

- Valerie Goins (Rogersville)

- Hannah Speaks (Surgoinsville)

- Dawson Fields (Rogersville)

- District 5: Rogersville

- Glenda Davis (Rogersville)

- Mark Dewitte (Rogersville)

- John C. Metz (Rogersville)

- District 6: Bean Station, Mooresburg and West Rogersville

- Nancy Barker (Rogersville)

- Larry Clonce (Rogersville)

- Rick Brewer (Mooresburg)

- District 7: Bulls Gap, Cherokee, & St. Clair

- Bob Edens (Bulls Gap)

- Charlie Newton (Rogersville)

- Robert Palmer (Rogersville)

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 500 square miles (1,300 km2), of which 487 square miles (1,260 km2) is land and 13 square miles (34 km2) (2.5%) is water.[11]

Adjacent counties

- Scott County, Virginia (north)

- Sullivan County (east)

- Washington County (southeast)

- Greene County (south)

- Hamblen County and Grainger County (southwest)

- Hancock County (west)

State protected area

- Kyles Ford Wildlife Management Area (part)

Other protected area

- Bays Mountain Park (part)

Other historic sites

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 6,563 | — | |

| 1810 | 7,643 | 16.5% | |

| 1820 | 10,949 | 43.3% | |

| 1830 | 13,683 | 25.0% | |

| 1840 | 15,035 | 9.9% | |

| 1850 | 13,370 | −11.1% | |

| 1860 | 16,162 | 20.9% | |

| 1870 | 15,837 | −2.0% | |

| 1880 | 20,610 | 30.1% | |

| 1890 | 22,246 | 7.9% | |

| 1900 | 24,267 | 9.1% | |

| 1910 | 23,587 | −2.8% | |

| 1920 | 22,918 | −2.8% | |

| 1930 | 24,117 | 5.2% | |

| 1940 | 28,523 | 18.3% | |

| 1950 | 30,494 | 6.9% | |

| 1960 | 30,468 | −0.1% | |

| 1970 | 33,726 | 10.7% | |

| 1980 | 43,751 | 29.7% | |

| 1990 | 44,565 | 1.9% | |

| 2000 | 53,563 | 20.2% | |

| 2010 | 56,833 | 6.1% | |

| 2020 | 56,721 | −0.2% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[12] 1790-1960[13] 1900-1990[14] 1990-2000[15] 2010-2014[3] | |||

2020 census

| Race | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 52,824 | 93.13% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 671 | 1.18% |

| Native American | 104 | 0.18% |

| Asian | 256 | 0.45% |

| Pacific Islander | 13 | 0.02% |

| Other/Mixed | 1,964 | 3.46% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 889 | 1.57% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 56,721 people, 23,135 households, and 15,917 families residing in the county.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 56,833 people living in the county. 96.5% were White, 1.3% Black or African American, 0.5% Asian, 0.2% Native American, 0.4% of some other race and 1.1% of two or more races. 1.2% were Hispanic or Latino (of any race). 47.0% were of American, 9.0% English, 8.0% German and 7.4% Irish ancestry.[19]

2000 census

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 53,563 people, 21,936 households, and 15,925 families living in the county. The population density was 110 people per square mile (42 people/km2). There were 24,416 housing units at an average density of 50 units per square mile (19/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 97.24% White, 1.55% Black or African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.23% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 0.23% from other races, and 0.56% from two or more races. 0.78% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 21,936 households, out of which 31.30% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 59.30% were married couples living together, 9.80% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.40% were non-families. 24.40% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.60% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 2.86.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 23.30% under the, 7.50% from 18 to 24, 30.00% from 25 to 44, 25.90% from 45 to 64, and 13.20% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 38 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.70 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 92.50 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $31,300, and the median income for a family was $37,557. Males had a median income of $30,959 versus $22,082 for females. The per capita income for the county was $16,073. About 12.70% of families and 15.80% of the population were below the poverty line, including 20.40% of those under age 18 and 17.70% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

According to a data profile produced by the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development in 2018,[21] the top employers in the county are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hawkins County Board of Education | 1,100 |

| 2 | BAE Systems Inc. | 850 |

| 3 | AGC Flat Glass North America, Inc. | 550 |

| 4 | Barrette Outdoor Living, Inc. | 500 |

| 5 | Cooper-Standard Automotive | 450 |

| 6 | Hutchinson Sealing Systems | 370 |

| 7 | TRW Automotive | 335 |

| 8 | Walmart (Kingsport) | 300 |

| 9 | Sam Dong, Inc. | 215 |

| 10 | Baldor Electric Company | 207 |

Transportation

Major highways

U.S. Route 11W

U.S. Route 11W U.S. Route 11E

U.S. Route 11E State Route 31

State Route 31 State Route 66

State Route 66 State Route 70, Trail of the Lonesome Pine

State Route 70, Trail of the Lonesome Pine State Route 66

State Route 66 State Route 94

State Route 94- State Route 113

- State Route 344

- State Route 346

- State Route 347

State Route 172 formerly went into Hawkins County, it now ends in Greene County at Interstate 81 exit 36 in the town of Baileyton.

Airports

The Hawkins County Airport is a county-owned public-use airport located six nautical miles (7 mi, 11 km) northeast of the central business district of Rogersville.[22]

Communities

Cities

- Church Hill

- Kingsport (partial)

Towns

- Bean Station (partial, mostly in Grainger)

- Bulls Gap

- Mount Carmel

- Rogersville (county seat)

- Surgoinsville

Census-designated place

Unincorporated communities

In popular culture

The film, The River, was filmed in Hawkins County and the surrounding area. Universal Studios purchased four hundred forty acres of land for the movie.[23]

The post-apocalyptic novel series "The Living Saga" (by Jaron McFall) takes place largely in Hawkins County. The main character, Cedric, is from Mooresburg and was a student at Cherokee High School in Rogersville.[24]

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third party(ies) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| 2020 | 20,405 | 82.20% | 4,083 | 16.45% | 336 | 1.35% |

| 2016 | 16,648 | 80.14% | 3,507 | 16.88% | 619 | 2.98% |

| 2012 | 14,382 | 72.50% | 5,088 | 25.65% | 367 | 1.85% |

| 2008 | 14,756 | 70.13% | 5,930 | 28.18% | 354 | 1.68% |

| 2004 | 13,447 | 66.46% | 6,684 | 33.04% | 102 | 0.50% |

| 2000 | 10,071 | 58.90% | 6,753 | 39.50% | 274 | 1.60% |

| 1996 | 8,164 | 51.21% | 6,367 | 39.94% | 1,410 | 8.85% |

| 1992 | 7,758 | 47.64% | 6,623 | 40.67% | 1,904 | 11.69% |

| 1988 | 9,356 | 63.88% | 5,212 | 35.59% | 78 | 0.53% |

| 1984 | 9,863 | 66.67% | 4,802 | 32.46% | 128 | 0.87% |

| 1980 | 7,836 | 57.92% | 5,283 | 39.05% | 410 | 3.03% |

| 1976 | 6,407 | 51.62% | 5,931 | 47.78% | 74 | 0.60% |

| 1972 | 7,791 | 72.31% | 2,608 | 24.20% | 376 | 3.49% |

| 1968 | 6,217 | 60.78% | 2,213 | 21.64% | 1,798 | 17.58% |

| 1964 | 5,712 | 57.68% | 4,191 | 42.32% | 0 | 0.00% |

| 1960 | 7,010 | 72.48% | 2,586 | 26.74% | 76 | 0.79% |

| 1956 | 6,916 | 68.04% | 3,180 | 31.29% | 68 | 0.67% |

| 1952 | 5,295 | 68.19% | 2,404 | 30.96% | 66 | 0.85% |

| 1948 | 3,637 | 62.50% | 2,019 | 34.70% | 163 | 2.80% |

| 1944 | 3,692 | 67.64% | 1,756 | 32.17% | 10 | 0.18% |

| 1940 | 3,314 | 60.72% | 2,108 | 38.62% | 36 | 0.66% |

| 1936 | 3,300 | 59.04% | 2,278 | 40.76% | 11 | 0.20% |

| 1932 | 2,890 | 54.51% | 2,391 | 45.10% | 21 | 0.40% |

| 1928 | 2,965 | 71.33% | 1,186 | 28.53% | 6 | 0.14% |

| 1924 | 2,600 | 61.22% | 1,596 | 37.58% | 51 | 1.20% |

| 1920 | 2,650 | 65.11% | 1,381 | 33.93% | 39 | 0.96% |

| 1916 | 1,739 | 60.03% | 1,142 | 39.42% | 16 | 0.55% |

| 1912 | 828 | 32.70% | 1,026 | 40.52% | 678 | 26.78% |

See also

- Flag of Hawkins County, Tennessee

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Hawkins County, Tennessee

References

- ^ a b Henry R. Price, "Hawkins County," Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Retrieved: 16 October 2013.

- ^ Origins Of Tennessee County Names, Tennessee Blue Book 2005-2006, pages 508-513

- ^ a b "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved December 2, 2013.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Stony Point". National Park Service. Retrieved May 11, 2018. With accompanying pictures

- ^ "Tennessee: Individual County Chronologies". Tennessee Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2007. Archived from the original on February 3, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. pp. 152.

- ^ Hodge, Tom (March 31, 1957). "Poor Valley State Park Proposed For ET Area". Johnson City Press. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Johnston, Sheila (October 27, 1976). "Poor Valley Park: The Wait Goes On". Kingsport Times-News. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "County Commission". Hawkins County, Tennessee. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2015.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Based on 2000 census data

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 27, 2021.

- ^ "American FactFinder". Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ "Hawkins County: County Profile Tool". Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development. State of Tennessee. 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ FAA Airport Form 5010 for RVN PDF. Federal Aviation Administration. Effective August 25, 2011.

- ^ The River (1984) - IMDb, retrieved February 9, 2020

- ^ McFall, Jaron (October 2018). Surviving. ISBN 978-1719826563.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved March 10, 2018.

External links

- County website

- Template:Curlie

- Hawkins County, TNGenWeb - free genealogy resources for the county