Norton, Massachusetts

Norton, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

Norton Town Common | |

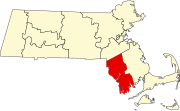

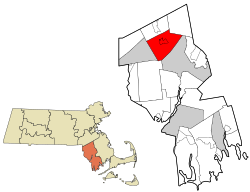

Location in Bristol County in Massachusetts | |

| Coordinates: 41°58′00″N 71°11′15″W / 41.96667°N 71.18750°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Bristol |

| Settled | 1669 |

| Incorporated | 1711 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| Area | |

• Total | 29.8 sq mi (77.2 km2) |

| • Land | 28.7 sq mi (74.4 km2) |

| • Water | 1.1 sq mi (2.9 km2) |

| Elevation | 105 ft (32 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 19,202 |

| • Density | 640/sq mi (250/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Code | 02766 |

| Area code | 508/774 |

| FIPS code | 25-49970 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619436 |

| Website | www.nortonma.org |

Norton is a town in Bristol County, Massachusetts, United States, and contains the villages of Norton Center and Chartley. The population was 19,202 at the 2020 census.[1] Home of Wheaton College, Norton hosts the Dell Technologies Championship, a tournament of the PGA Tour held annually on the Labor Day holiday weekend at the TPC Boston golf club.

History

Winnecunnet Lake was an ancient fishing, hunting, and camping site known for thousands of years by Indigenous Pokanoket and Mattakeeset families.[2] In the old days before dams and other obstructions, rivers running gently into the lake and swamplands around it provided canoe routes north to Lake Massapoag and south to the Taunton River. Growing tall in the lowlands along two of Norton’s main waterways—Wading and Rumford—- and continuing further along their convergence into Three Mile River, a thick forest of cedar trees grew dark and intertwined together. These swampy forests were places of safety in the winter, when the wet uneven ground was frozen over and the thick tree branches kept families and animals alike more shaded from the wind and snow.

The deep inland swamps of Norton remained unsettled by English colonists for many years after their initial arrival on the Massachusetts coast. But by the late 1640s, the townships of Rehoboth and Taunton were looking to expand their bounds to the north, south, and west. The settlement of Rehoboth bought the lands north of it—what would become Attleboro—from Wamsutta in the 1666 North Purchase.[3] Taunton, too, was looking to acquire more land to develop into meadows and pastureland, cutting the forests back and using the felled timber to feed the construction and fuel industries.[4] The forests and swampland of Norton were first legally settled by European colonists after the Taunton North Purchase in 1668.[5] This deed of purchase from Metacomet entitled the men of Taunton to the lands above their current settlement—in the upland forests, cedar swamps, rivers, meadows, and lakes that would become established as Norton, Mansfield, and Easton. In 1686, more payments to access rights for the North Purchase lands were made by Taunton men to Josias Wampatuck, a descendent of Chickatabut.[6] During King Philip’s War, “a group of twenty Taunton men, fearing attack" against their settlement "followed the Three Mile River to its confluence… at the Coweset (Wading) and Rumford Rivers and the thick swamp between them,”[7] attacking women and children who were sheltering there. In this fight, at Norton's so-called "Lockety Neck," the men murdered or otherwise participated in the killing of Weetamoo, the saunkskwa leader of the Pocasset Wampanoag people.[8] There is a memorial plaque on Pine Street commemorating her and other Wampanoag people killed in this battle.[9]

When Norton was first settled in 1669 it was called North Taunton for its location on the northern border of Taunton, Massachusetts. The town was renamed "Norton"—after Norton, Oxfordshire, England, where many early settlers had originated[10]—when the town was officially established on March 17, 1710. Parts of Norton were set out as Easton on December 21, 1725, and as Mansfield on April 26, 1770.[11]

Metacomet, the Wampanoag Indian sachem also known as "King Phillip", used to camp at a cave made by huge glacial rocks resting on top of each other, just north-east of Lake Winnecunnet. Every Norton school child has been entertained with the legend of King Phillip's Cave.[12]

The bandstand within the town center was originally erected using donated funds during the first Gulf War, in honor of the veterans who served from Norton.

In elementary school, students were told the story of the "Devil's Foot Print", where Major George Leonard sold his soul to the devil.[13] The devil's foot print can be seen at Norton's Joseph C. Solmonese Elementary School, on land which was once Leonard's farmland. Every 26 years, the school unburies a time capsule, the last of which was buried in 1999. The time capsule will be opened next in 2026. The Sun Chronicle describes:

Norton is a small but slowly-evolving town.

So it was in December 1997, when a traffic light was installed at the intersection of routes 123 and 140 in Norton. It was the town's first full traffic light and, in a manner of speaking, it declared "Norton isn't Mayberry anymore."[14]

Norton is also a location in the claimed paranormal Bridgewater Triangle.

Geography and transit

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 29.8 square miles (77 km2), of which 28.7 square miles (74 km2) is land and 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2), or 3.72%, is water. Norton is generally low and swampy. The waters of the area are fed by the Wading River and the Canoe River, both of which feed into the Taunton River downstream. The two largest bodies of water in town are the Norton Reservoir, north of the center of town, and Winnecunnet Pond on the east (on the north side of I-495), which is fed by the Canoe River and feeds into the Mill River.

Lake Winnecunnet is Norton’s only natural body of water. Classified as a kettle pond, it formed over 13,000 years ago when a large chunk of glacial ice rested there and gradually melted, creating the lake as the climate slowly warmed.[15]

The town, an irregular polygon generally oriented from northeast to southwest, is bordered by Easton to the northeast, Taunton to the southeast, Rehoboth to the south, Attleboro to the southwest, and Mansfield to the northwest. Norton is approximately 27 miles south-southwest of Boston, and 15 miles northeast of Providence, Rhode Island.

Norton is served by Interstate 495 and Massachusetts Routes 123 and 140, which meet at the center of town. There is an exit off I-495 for Route 123 in the eastern part of town, and 140's exit to the interstate lies just north of the Mansfield town line. One route of the Greater Attleboro Taunton Regional Transit Authority (GATRA) runs through town, linking the two cities on either side. The Middleboro Subdivision passes through the town, with 4.5 miles (7.35 km) of railroad track crossing the southern quarter of town, linking lines in Attleboro and Taunton. The Providence/Stoughton Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail system has stops in both Attleboro and Mansfield nearby, providing rail access to Providence and Boston. The nearest municipal airport is in neighboring Mansfield, with the nearest national and international flights being either from Boston's Logan International Airport or T.F. Green Airport in Warwick, Rhode Island.

Transportation

The town is bisected southeast to northwest by Interstate 495, as well as Massachusetts Route 140 from north to south and Massachusetts Route 123 from southwest to northeast. Exit 10 off I-495 links the highway with Route 123. Exit 9 (Bay Street, Taunton) and Exit 11 (Route 140, Mansfield) are just over the town lines. Route 140 and Route 123 intersect at the center of town, by the town green. Although it is not officially signed as such, many fans attending concerts and events at the Xfinity Center (formerly the Tweeter Center, and originally the Great Woods Center for the Performing Arts) reach the venue by driving along Route 123 to Route 140. The town is also a part of the Greater Attleboro Taunton Regional Transit Authority (or GATRA) bus line. The nearest MBTA station is in Mansfield.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,966 | — |

| 1860 | 1,848 | −6.0% |

| 1870 | 1,821 | −1.5% |

| 1880 | 1,782 | −2.1% |

| 1890 | 1,785 | +0.2% |

| 1900 | 1,826 | +2.3% |

| 1910 | 2,544 | +39.3% |

| 1920 | 2,374 | −6.7% |

| 1930 | 2,737 | +15.3% |

| 1940 | 3,107 | +13.5% |

| 1950 | 4,401 | +41.6% |

| 1960 | 6,818 | +54.9% |

| 1970 | 9,487 | +39.1% |

| 1980 | 12,690 | +33.8% |

| 1990 | 14,265 | +12.4% |

| 2000 | 18,036 | +26.4% |

| 2010 | 19,031 | +5.5% |

| 2020 | 19,202 | +0.9% |

Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25] | ||

As of the census[26] of 2000, there were 18,036 people, 5,872 households, and 4,474 families residing in the town. These residents are often referred to as either "Nortonites" or "Nortonians", though the term "Norts" is often used in colloquial context. The population density was 628.3 inhabitants per square mile (242.6/km2). There were 5,961 housing units at an average density of 207.7 per square mile (80.2/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 92.15% White, 1.16% African American, 0.13% Native American, 1.00% Asian, 0.01% Pacific Islander, 4.47% from other races, and 1.08% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.14% of the population.

There were 5,872 households, out of which 42.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 61.8% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 23.8% were non-families. 19.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.79 and the average family size was 3.22.

In the town, the population was spread out, with 27.0% under the age of 18, 12.6% from 18 to 24, 32.2% from 25 to 44, 20.5% from 45 to 64, and 7.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 90.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 86.1 males.

According to a 2016 estimate, the median income for a household in the town was $80,806, and the median income for a family in 2016 was estimated at $104,176.[27][28] Males had a median income of $51,133 versus $33,149 for females. The per capita income for the town was $23,876. About 2.2% of families and 4.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 2.9% of those under age 18 and 12.9% of those age 65 or over.

Government

State and national government

The town is a part of three separate state representative districts; precinct one belonging to the Fourth Bristol district (which includes all of Rehoboth, Seekonk and part of Swansea), precinct two belonging to the Fourteenth Bristol district (which includes parts of North Attleborough, Attleboro and Mansfield as well), and precincts three through five belonging to the First Bristol district (whose district includes Mansfield Center and Foxborough). The town is a part of the state senate district of the Bristol and Norfolk district, stretching from Dover to the north to Rehoboth and Seekonk to the south. James Timilty served as State Senator until 2017 for the Bristol & Norfolk district. Upon his retirement, he was succeeded by State Senator Paul Feeney. State Representatives Steven S. Howitt and Frederick J. Barrows serve the Town. Norton is patrolled by Troop H (Metro Boston District), Third (Foxborough) Barracks of the Massachusetts State Police.

On the national level, the town is part of Massachusetts Congressional District 4, which is represented by Joseph P. Kennedy III. The state's senior Senator, newly elected in 2012, is Elizabeth Warren and the state's junior Senator is currently Ed Markey.

Town government and services

The town has an open town meeting form of government, with a town manager and a board of selectmen governing the town. The town is served by the central police station (next to the town hall on Route 123), three fire stations (Station 2 on Route 123, Station 1 in Chartley (currently closed), and Station 5 (Fire Alarm) in Barrowsville), and two post offices (Norton, next to the town center and Wheaton College; and Chartley, near the Attleboro line along Route 123). The town's public library is located next to the town hall, although the original still stands on Route 140 at the town green. There is also a senior center located along Route 123 near the high school.

Education

Norton has its own public school system, Norton Public Schools. There are three elementary schools: L.G. Nourse Elementary School (K–3) on the east side, J.C. Solomonese Elementary School (Pre-K–3) in Chartley, and H.A. Yelle Elementary School (4–5) near the center of town. The Norton Middle School (6–8) is located in Chartley. Norton High School (9–12) is located near the center of town, next to the H.A. Yelle School. The school colors are purple and white and their mascot is a lancer.

High school students may also attend Southeast Regional Vocational-Technical High School in Easton or Bristol County Agricultural High School, otherwise known as "Bristol Aggie", in Dighton free of charge. There are two private schools in town, Life Church, a Baptist school which serves grades K–12, and the Pinecroft School on 33 Pine Street. Many students also attend private or parochial schools in the surrounding communities. Norton is also home to Wheaton College.

Notable people

- Troy Brown, former New England Patriots wide receiver[29]

- George L. Clarke (1813–1890), Mayor of Providence 1869–1870, was born in Norton

- Jonathan Eddy, colonel in the American Revolution

See also

- Greater Taunton Area

- Shpack Landfill Superfund site

- Taunton River Watershed

References

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Norton town, Bristol County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 10, 2021.

- ^ George Faber Clarke, "History of Norton" 1859, p. 51.

- ^ Leonard Bliss, "History of Rehoboth, 1836, pg. 50.

- ^ Emery, "History of Taunton," p. 103, 108.

- ^ Emery, "History of Taunton," p. 109.

- ^ Henry Williams, 1880, “Was Elizabeth Pool the First Purchaser,” Old Colony Historical Society, p. 51.

- ^ (Lisa Brooks, 2018, "Our Beloved Kin," p. 324.

- ^ Lisa Brooks, 2018, "Our Beloved Kin," p. 34.

- ^ "Historical war site marked in Norton". May 25, 2010.

- ^ Clark, George Faber (1859). A History of the Town of Norton, Bristol County, Massachusetts, from 1669 to 1859. Crosby, Nichols, and Company. pp. 34, 35.

- ^ Norton: Your Town[permanent dead link]

- ^ MGA Links at Mamantapett Archived 2006-02-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ https://archive.org/details/devilsfootprints00yell/page/28/mode/2up Yelle, The Devil's Footprints and Other Sketches of Old Norton, p. 28.

- ^ Sun Chronicle Online

- ^ https://www.nortonma.org/sites/g/files/vyhlif3606/f/uploads/2017_section_4a_environment_inventory_and_analysis_part_i_page_32-44.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Economy in Norton, Massachusetts". Bestplaces.net. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Norton, Massachusetts (MA 02766) profile: Population, maps, real estate, averages, homes, statistics, relocation, travel, jobs, hospitals, schools, crime, moving, houses, news, sex offenders".

- ^ Voss, Gretchen (May 15, 2006). "The Secret Lives of the Players' Wives". Boston Magazine. Retrieved February 4, 2019.