Lindisfarne Gospels

The Lindisfarne Gospels (London, British Library Cotton MS Nero D.IV) is an illuminated manuscript gospel book probably produced around the years 715–720 in the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, which is now in the British Library in London.[1] The manuscript is one of the finest works in the unique style of Hiberno-Saxon or Insular art, combining Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic elements.[2]

The Lindisfarne Gospels are presumed to be the work of a monk named Eadfrith, who became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 698 and died in 721.[3] Current scholarship indicates a date around 715, and it is believed they were produced in honour of St. Cuthbert. However, some parts of the manuscript were left unfinished so it is likely that Eadfrith was still working on it at his time of death.[3] It is also possible that he produced them prior to 698, in order to commemorate the elevation of Cuthbert's relics in that year,[4] which is also thought to have been the occasion for which the St Cuthbert Gospel (also in the British Library) was produced. The Gospels are richly illustrated in the insular style and were originally encased in a fine leather treasure binding covered with jewels and metals made by Billfrith the Anchorite in the 8th century. During the Viking raids on Lindisfarne this jewelled cover was lost and a replacement was made in 1852.[5] The text is written in insular script, and is the best documented and most complete insular manuscript of the period.

An Old English translation of the Gospels was made in the 10th century: a word-for-word gloss of the Latin Vulgate text, inserted between the lines by Aldred, Provost of Chester-le-Street. This is the oldest extant translation of the Gospels into the English language.[6] The Gospels may have been taken from Durham Cathedral during the Dissolution of the Monasteries ordered by Henry VIII and were acquired in the early 17th century by Sir Robert Cotton from Robert Bowyer, Clerk of the Parliaments. Cotton's library came to the British Museum in the 18th century and went to the British Library in London when this was separated from the British Museum.[7]

Historical context

Lindisfarne, also known as "Holy Island", is located off the coast of Northumberland in northern England (Chilvers 2004). In around 635 AD, the Irish missionary Aidan founded the Lindisfarne monastery on "a small outcrop of the land" on Lindisfarne.[8] King Oswald of Northumbria sent Aidan from Iona to preach to and baptise the pagan Anglo-Saxons, following the conversion to Christianity of the Northumbrian monarchy in 627. By the time of Aidan's death in 651, the Christian faith was becoming well-established in the area.[9] The Lindisfarne gospel book is associated with the Cult of St. Cuthbert. Cuthbert was an ascetic member of a monastic community in Lindisfarne, before his death in 687. The book was made as part of the preparations to translate Cuthbert's relics to a shrine in 698. Lindisfarne has a reputation as the probable place of genesis according to the Lindisfarne Gospels. Around 705 an anonymous monk of Lindisfarne wrote the Life of St Cuthbert. His bishop, Eadfrith, swiftly commissioned the most famous scholar of the age, Bede, to help shape the cult to a new purpose.[10]

In the 10th century, about 250 years after the production of the book, Aldred, a priest of the monastery at Chester-le-Street, added an Old English translation between the lines of the Latin text. In his colophon he recorded the names of the four men who produced the Lindisfarne Gospels:[8] Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne, was credited with writing the manuscript; Ethelwald, Bishop of the Lindisfarne islanders, was credited with binding it; Billfrith, an anchorite, was credited with ornamenting the manuscript; and finally, Aldred lists himself as the person who glossed it in Anglo-Saxon (Old English).[11]

Some scholars have argued that Eadfrith and Ethelwald did not produce the manuscript but commissioned someone else to do so.[12] However, Janet Backhouse argues for the validity of the statement by pointing out that "there is no reason to doubt [Aldred's] statement" because he was "recording a well-established tradition".[8] Eadfrith and Ethelwald were both bishops at the monastery of Lindisfarne where the manuscript was produced. As Alan Thacker notes, the Lindisfarne Gospels are "undoubtedly the work of a single hand", and Eadfrith remains regarded as "the scribe and painter of the Lindisfarne Gospels".[13]

Commission

The Lindisfarne Gospels is a Christian manuscript, containing the four gospels recounting the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The manuscript was used for ceremonial purposes to promote and celebrate the Christian religion and the word of God.[14] Because the body of Cuthbert was buried there, Lindisfarne became an important pilgrimage destination in the 7th and 8th centuries, and the Lindisfarne Gospels would have contributed to the cult of St Cuthbert.[14] The gospels used techniques reminiscent of elite metalwork to impress a Northumbrian audience, most of whom could not read, and certainly not understand the Latin text.

According to Aldred's colophon, the Lindisfarne Gospels were made in honour of God and Saint Cuthbert, a Bishop of the Lindisfarne monastery who was becoming "Northern England's most popular Saint".[15] Scholars think that the manuscript was written sometime between Cuthbert's death in 687 and Eadfrith's death in 721.[14] There is a significant amount of information known about Cuthbert thanks to two accounts of his life that were written shortly after his death, the first by an anonymous monk from Lindisfarne, and the second by Bede, a famous monk, historian, and theologian.[9]

Cuthbert entered into the monastery of Melrose, now in lowland Scotland but then in Northumbria, in the late 7th century, and after being ordained a priest he began to travel throughout Northumbria, "rapidly acquiring a reputation for holiness and for the possession of miraculous powers".[16] The Synod of Whitby in 664 pitted the Hiberno-Celtic church against the Roman church regarding the calculation of the date of Easter. The dispute was adjudged by King Oswiu of Northumbria in favour of the Roman church, but many of the leading monks at Lindisfarne then returned to Iona and Ireland, leaving only a residue of monks affiliated to the Roman church at Lindisfarne. Due to increasingly slack religious practice in Lindisfarne, Cuthbert was sent to Lindisfarne to reform the religious community.[17] In Lindisfarne Cuthbert began to adopt a solitary lifestyle, eventually moving to Inner Farne Island, where he built a hermitage.[17] Cuthbert agreed to become bishop at the request of King Ecgfrith in 684, but within about two years he returned to his hermitage in Farne as he felt death approaching. Cuthbert died on 20 March 687 and was buried in Lindisfarne. As a venerated saint, his tomb attracted many pilgrims to Lindisfarne.[18]

Techniques

The Lindisfarne Gospels manuscript was produced in a scriptorium in the monastery of Lindisfarne. It took approximately 10 years to create.[19] Its pages are vellum, and evidence from the manuscript reveals that the vellum was made using roughly 150 calf skins.[20] The book is 516 pages long. The text is written "in a dense, dark brown ink, often almost black, which contains particles of carbon from soot or lamp black".[21] The pens used for the manuscript could have been cut from either quills or reeds, and there is also evidence to suggest that the trace marks (seen under oblique light) were made by an early equivalent of a modern pencil.[22] Lavish jewellery, now lost, was added to the binding of the manuscript later in the 8th century.[23] Eadfrith manufactured 90 of his own colours with "only six local minerals and vegetable extracts".[19]

There is a huge range of individual pigments used in the manuscript. The colours are derived from animal, vegetable and mineral sources.[24] Gold is used in only a couple of small details.[23] While some colours were obtained from local sources, others were imported from the Mediterranean.[24] The blue was long thought to be ultramarine from Afghanistan, but analysis with Raman microscopy in the 2000s revealed it to be indigo.[25] The medium used to bind the colours was primarily egg white, with fish glue perhaps used in a few places.[23] Backhouse emphasizes that "all Eadfrith's colours are applied with great skill and accuracy, but ... we have no means of knowing exactly what implements he used".

Professor Brown added that Eadfrith "knew about lapis lazuli [a semi-precious stone with a blue tint] from the Himalayas but could not get hold of it, so made his own [substitute]".[23]

The pages were arranged into gatherings of eight. Once the sheets had been folded together, the highest-numbered page was carefully marked out by pricking with a stylus or a small knife.[21] Holes were pricked through each gathering of eight leaves, and then individual pages were separately ruled for writing with a sharp, dry, and discrete point.[21]

The Lindisfarne Gospels are impeccably designed, and as Backhouse points out, vellum would have been too expensive for "practice runs" for the pages, and so preliminary designs may have been done on wax tablets (hollowed-out wood or bone with a layer of wax).[26] These would have been an inexpensive medium for a first draft; once a sketch had been transferred to the manuscript, the wax could be remelted and a new design or outline inscribed.[26]

History

As a result of Viking raids, the monastic community left Lindisfarne around 875, taking with them Cuthbert's body, relics, and books, including the Lindisfarne Gospels[14] and the St Cuthbert Gospel. It is estimated that after around seven years the Lindisfarne community settled in the Priory at Chester-le-Street in Durham, where they stayed until 995 (and where Aldred would have done his interlinear translation of the text).[27] After Henry VIII ordered the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539, the manuscript was separated from the priory.[27] In the early 17th century the Gospels were owned by Sir Robert Cotton (1571–1631), and in 1753 they became part of the founding collections of the British Museum.[28]

Condition

The Lindisfarne Gospels are in remarkable condition and the text is complete and undamaged.[29] However, the original binding of the manuscript was destroyed. In March 1852 a new binding was commissioned by bishop Edward Maltby; Smith, Nicholson and Co. (silversmiths) made the binding with the intention of recreating motifs in Eadfrith's work.[30]

Formal and stylistic elements of the manuscript

In The Illuminated Manuscript, Backhouse states that "The Lindisfarne Gospels is one of the first and greatest masterpieces of medieval European book painting".[31] The Lindisfarne Gospels is described as Insular or Hiberno-Saxon art, a general term for manuscripts produced in the British Isles between 500 and 900 AD.[27]

As a part of Anglo-Saxon art the manuscript reveals a love of riddles and surprise, shown through the pattern and interlace in the meticulously designed pages. Many of the patterns used for the Lindisfarne Gospels date back before the Christian period.[32] There is a strong presence of Celtic, Germanic, and Irish art styles. The spiral style and "knot work" evident in the formation of the designed pages are influenced by Celtic art.[32]

One of the most characteristic styles in the manuscript is the zoomorphic style (adopted from Germanic art) and is revealed through the extensive use of interlaced animal and bird patterns throughout the book.[32] The birds that appear in the manuscript may also have been from Eadfrith's own observations of wildlife in Lindisfarne.[27] The geometric design motifs are also Germanic influence, and appear throughout the manuscript.

The carpet pages (pages of pure decoration) exemplify Eadfrith's use of geometrical ornamentation. Another notable aspect of the Gospels is the tiny drops of red lead, which create backgrounds, outlines, and patterns, but never appear on the carpet pages.[33] The red dots appear in early Irish manuscripts, revealing their influence in the design of the Lindisfarne Gospels.[33] Thacker points out that Eadfrith acquired knowledge from, and was influenced by, other artistic styles, showing that he had "eclectic taste".[34] While there are many non-Christian artistic influences in the manuscript, the patterns were used to produce religious motifs and ideas.

Eadfrith was a highly trained calligrapher and he used insular majuscule script in the manuscript.[34]

Insular context

The Lindisfarne Gospels are not an example of "isolated genius... in an otherwise dark age":[35] there were other Gospel books produced in the same time period and geographic area that have similar qualities to the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Lindisfarne monastery not only produced the Lindisfarne gospels, but the Durham Gospels and Echternach Gospels as well. These gospel books were credited to "the 'Durnham-Echternach Calligrapher', thought to be the oldest member of the Lindisfarne Scriptorium".[36] The Echternach gospels might have been made during the creation of the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Durham Gospels came after, but in an old-fashioned style.[37] The Lichfield Gospels (Lichfield Cathedral, Chapter Library) employ a very similar style to the Lindisfarne Gospels, and it is even speculated that the artist was attempting to emulate Eadfrith's work.[29] Surviving pages from the Lichfield Gospels also have a cross-carpet page and animal and bird interlace, but the designs do not achieve the same perfection, and are seen as looser and heavier than Eadfrith's.[29]

The design of the Lindisfarne Gospels has also been related to the Tara Brooch (National Museum of Ireland, Dublin), displaying animal interlace, curvilinear patterns, and borders of bird interlace, but unfortunately the origin of the brooch is unknown.[29] The Durham Gospels (Durham Cathedral Library) are suspected as having been created slightly earlier than the Lindisfarne Gospels, and while they have the bird interlace, the birds are less natural and real than Eadfrith's birds in the Lindisfarne Gospels.[38] The Book of Durrow (Trinity College, Dublin) is also thought of as an earlier insular manuscript, as the style of the manuscript is simpler and less developed than that of the Lindisfarne Gospels.[39] The Book of Kells (Trinity College, Dublin, MS A. I.6 (58)) employs decorative patterns that are similar to other insular art pieces of the period, but is thought to have been produced much later than the Lindisfarne Gospels.[40]

Iconography

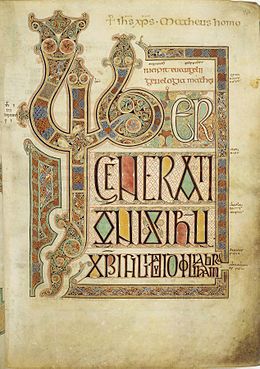

The Lindisfarne Gospels is a manuscript that contains the Gospels of the four Evangelists Mark, John, Luke, and Matthew. The Lindisfarne Gospels begins with a carpet page in the form of a cross and a major initial page, introducing the letter of St. Jerome and Pope Damasus I.[27] There are sixteen pages of arcaded canon tables, where parallel passages of the four Evangelists are laid out.[41] A portrait of the appropriate Evangelist, a carpet page and a decorated initial page precedes each Gospel. There is an additional major initial of the Christmas narrative of Matthew.[27]

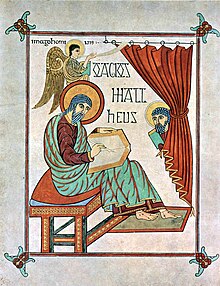

The Evangelists

Bede explains how each of the four Evangelists was represented by their own symbol: Matthew was the man, representing the human Christ; Mark was the lion, symbolising the triumphant Christ of the Resurrection; Luke was the calf, symbolising the sacrificial victim of the Crucifixion; and John was the eagle, symbolising Christ's second coming.[42] A collective term for the symbols of the four Evangelists is the Tetramorphs. Each of the four Evangelists is accompanied by their respective symbol in their miniature portraits in the manuscript. In these portraits, Matthew, Mark, and Luke are shown writing, while John looks straight ahead at the reader holding his scroll.[42] The Evangelists also represent the dual nature of Christ. Mark and John are shown as young men, symbolising the divine nature of Christ, and Matthew and Luke appear older and bearded, representing Christ's mortal nature.[42]

The decoration of the manuscript

A manuscript so richly decorated reveals that the Lindisfarne Gospels not only had a practical ceremonial use, but also attempted to symbolize the Word of God in missionary expeditions.[43] Backhouse points out that the clergy was not unaware of the profound impression a book such as the Lindisfarne Gospels made on other congregations.[43] The opening words of the Gospel (the incipits) are highly decorated, revealing Roman capitals, Greek and Germanic letters, filled with interlaced birds and beasts, representing the splendour of God's creation.[42] On one page alone, there are 10,600 decorative red dots.[44] Different kinds of pigment are used throughout the manuscript.[24] Red lead and gold were also used for decoration.[23][33]

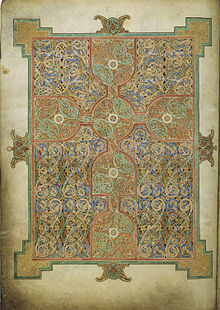

The carpet pages

Each carpet page contains a different image of a cross (called a cross-carpet page), emphasising the importance of the Christian religion and of ecumenical relationships between churches.[42] The pages of ornamentation have motifs familiar from metalwork and jewellery that pair alongside bird and animal decoration.[27]

Campaign to relocate

A campaign exists to have the gospels housed in the North East of England. Supporters include the Bishop of Durham, Viz creator Simon Donald, and the Northumbrian Association. The move is vigorously opposed by the British Library.[45][46] Several possible locations have been mooted, including Durham Cathedral, Lindisfarne itself or one of the museums in Newcastle upon Tyne or Sunderland.[5] In 1971 professor Suzanne Kaufman of Rockford, Illinois, presented a facsimile copy of the Gospels to the clergy of the Island.[47]

Exhibitions in the north of England

Between September and 3 December 2022 the manuscript was being exhibited in the Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle upon Tyne.[48]

From July to September 2013 the Lindisfarne Gospels were displayed in Palace Green Library, Durham. Nearly 100,000 visitors saw the exhibition.[49] The manuscript exhibition also included items from the Staffordshire Hoard, the Yates Thompson 26 Life of Cuthbert, and the gold Taplow belt buckle.[50] Also included was the closely related St Cuthbert Gospel, which was bought by the British Library in 2012. This returned to Durham in 2014 (1 March to 31 December) for an exhibition of bookbindings at the library. Alongside the Lindisfarne Gospels Exhibition was a festival of more than 500 events, exhibitions and performances across the North East and Cumbria.

See also

Notes

- ^ "Lindisfarne Gospels" The British Library, in 2018 dates it "c. 715-720".

- ^ Hull, Derek (2003). Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Art: Geometric Aspects. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-549-X.

- ^ a b Lindisfarne Gospels British Library. Retrieved 2008-03-21

- ^ Backhouse, Janet (1981). The Lindisfarne Gospels. Phaidon. ISBN 9780714824611.

- ^ a b Let Gospels come home Archived 19 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine Sunderland Echo, 2006-09-22. Retrieved 2008-03-21

- ^ "The Lindisfarne Gospels". Northumbrian Association. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 24 December 2012.

- ^ Time line British Library. Retrieved 2008-03-21

- ^ a b c Backhouse 1981, 7.

- ^ a b Backhouse 1981, 8.

- ^ Brown, Michelle (2003). The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality & the Scribe. London, The British Library: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 12.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 13.

- ^ Thacker 2004.

- ^ a b c d BBC Tyne 2012

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 7; Chilvers 2004.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 8–9.

- ^ a b Backhouse 1981, 9.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 9–10.

- ^ a b Consiglio, Flavia Di (20 March 2013). "Lindisfarne Gospels: Why Is This Book so Special?". BBC. Archived from the original on 21 March 2013.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 27.

- ^ a b c Backhouse 1981, 28.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 28–31.

- ^ a b c d e Backhouse 1981, 32.

- ^ a b c Backhouse 2004.

- ^ Brown, Katherine L.; Clark, Robin J. H. (January 2004). "The Lindisfarne Gospels and Two Other 8th Century Anglo-Saxon/Insular Manuscripts: Pigment Identification by Raman Microscopy". Journal of Raman Spectroscopy. 35 (1): 4–12. Bibcode:2004JRSp...35....4B. doi:10.1002/jrs.1110.

- ^ a b Backhouse 1981, 31.

- ^ a b c d e f g Backhouse, 2004

- ^ Chilvers 2004

- ^ a b c d Backhouse 1981, 66

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 90

- ^ Backhouse 1979, 10

- ^ a b c Backhouse 1981, 47

- ^ a b c Backhouse 1981, 51

- ^ a b Thacker 2004

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 62

- ^ Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality & the Scribe. London: The British Library, 2003.

- ^ Brown, Michelle (2003). The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality & the Scribe. London: University of Toronto Press.

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 67

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 75

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 41

- ^ Backhouse 1981, 41; Backhouse 2004

- ^ a b c d e The British Library Board, "The Lindisfarne Gospels Tour." Accessed 13 March 2012.

- ^ a b Backhouse 1981, 33

- ^ Consiglio, Flavia Di. "Lindisfarne Gospels: Why Is This Book so Special?" BBC News, BBC, 20 Mar. 2013, www.bbc.co.uk/religion/0/21588667.

- ^ Viz creator urges gospels return BBC News Online, 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2008-03-21

- ^ Hansard, see column 451 Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Speech by the Bishop of Durham in the House of Lords in 1998. Retrieved 2009-03-25

- ^ Rockford [Illinois] Register-Star, Sunday 9-27-1970. She led the effort to donate the text after visiting Lindisfarne Island the previous year. Rockford College sponsored the fundraising for the facsimile. She was a professor of art at the college.

- ^ Laing Art Gallery

- ^ "Lindisfarne Gospels Durham exhibition attracts 100,000 visitors", BBC News, Tyne, accessed 5 December 2013

- ^ Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition website Archived 11 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

References

- Backhouse, Janet. "Lindisfarne Gospels." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Accessed 10 March 2012.

- Backhouse, Janet. The Illuminated Manuscript. Oxford: Phaidon Press Ltd., 1979.

- Backhouse, Janet. The Lindisfarne Gospels. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1981.

- BBC Tyne. "The Lindisfarne Gospels." BBC Online, 2012. Accessed 10 March 2012.

- Calkins, Robert G. Illuminated Books of the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1983.

- Chilvers, Ian. ed. "Lindisfarne Gospels" The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Accessed 9 March 2012.

- De Hamel, Christopher. A History of Illuminated Manuscripts. Boston: David R. Godine, 1986.

- Thacker, Alan. Eadfrith (d. 721?). doi: 8381, 2004.

- Walther, Ingo F. and Norbert Wolf. Codices Illustres: The world's most famous illuminated manuscripts, 400 to 1600. Köln, TASCHEN, 2005.

- Whitfield, Niamh. "The “Tara” brooch: an Irish emblem of status in its European context", In: Hourihane, Colm (ed), From Ireland Coming: Irish art from the early Christian to the late Gothic period and its European context. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-6910-8825-9

- "Lindisfarne Gospels." The British Library, The British Library, 16 Jan. 2015.

- Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality & the Scribe. London: The British Library, 2003.

- Consiglio, Flavia Di. "Lindisfarne Gospels: Why Is This Book so Special?" BBC News, BBC, 20 Mar. 2013.

Further reading

- Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels: Society, Spirituality and the Scribe. London: The British Library, 2003

- Brown, Michelle P., The Lindisfarne Gospels and the Early Medieval World. London: The British Library, 2010

External links

- British Library Digitised Manuscripts Digital facsimile of the entire manuscript

- Turning the Pages Leaf through the Lindisfarne Gospels online using the British Library's Turning the Pages software (requires Shockwave plugin)

- The Lindisfarne Gospels, a free online seminar from the British Library.

- Lindisfarne Gospels: information, zoomable image British Library website

- British Library Digital Catalogue of Illuminated Manuscripts entry

- More information at Earlier Latin Manuscripts

- Sacred Texts: Lindisfarne Gospels

- "The Lindisfarne Gospels", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Michelle Brown, Richard Gameson & Clare Lees (In Our Time, Feb.20, 2003)