Japan–Portugal relations

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (March 2014) |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Japanese. (December 2013) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

Japan |

Portugal |

|---|---|

Japanese–Portugal relations are the foreign relations between Japan and Portugal. Although Portuguese sailors visited Japan first in 1543, diplomatic relations started in the nineteenth century.

History

16th century

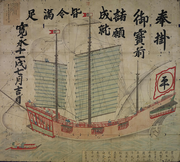

The first affiliation between Portugal and Japan started in 1543, when Portuguese explorers landed in the southern archipelago of Japan, becoming the first Europeans to reach Japan. This period of time is often entitled Nanban trade, where both Europeans and Asians would engage in mercantilism. The Portuguese at this time would found the port of Nagasaki, through the initiative of the Jesuit Gaspar Vilela and the Daimyo lord Ōmura Sumitada, in 1571.

The expansion for commerce extended Portuguese influence in Japan, particularly in Kyushu, where the port became a strategic hot spot after the Portuguese assistance to Daimyo Sumitada on repelling an attack on the harbor by the Ryūzōji clan in 1578.

The cargo of the first Portuguese ships upon docking in Japan were basically cargo coming from China (silk, porcelain, etc.). The Japanese craved these goods, which were prohibited from the contacts with the Chinese by the Emperor as punishment for the attacks of the Wokou piracy. Thus, the Portuguese acted as intermediaries in Asian trade.

In 1592 the Portuguese trade with Japan started being increasingly challenged by Chinese smugglers on their reeds, in addition to Spanish vessels coming to Manila in 1600, the Dutch in 1609, and English in 1613.

One of the many things that the Japanese were interested in were Portuguese guns. The first three Europeans to arrive in Japan in 1543 were Portuguese traders António Mota, Francisco Zeimoto and António Peixoto (also presumably Fernão Mendes Pinto). They arrived at the southern tip of Tanegashima, where they would introduce firearms to the local population. These muskets would later receive the name after its location.

Because Japan was in the midst of a civil war, called the Sengoku period, the Japanese bought many Portuguese guns. Oda Nobunaga, a famous daimyo who nearly unified all of Japan, made extensive use of guns (arquebus) playing a key role in the Battle of Nagashino. Within a year, Japanese smiths were able to reproduce the mechanism and began to mass-produce the Portuguese arms. Later on, Tanegashima firearms were improved and Japanese matchlocks were of superior quality. As with Chinese experimentation with firearms of this period, the Japanese developed better sights and cord protection. And just 50 years later, his armies were equipped with a number of weapons perhaps greater than any contemporary army in Europe. The weapons were extremely important in the unification of Japan under Toyotomi Hideyoshi and Tokugawa Ieyasu, as well as in the invasions of Korea in 1592 and 1597. Europeans brought by trade not only weapons, but also soap, tobacco, and other unknown products in Feudal Japan.

After the Portuguese first made contact with Japan in 1543, a large scale slave trade developed in which Portuguese purchased Japanese as slaves in Japan and sold them to various locations overseas, including Portugal itself, throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[1][2] Many documents mention the large slave trade along with protests against the enslavement of Japanese. Hundreds of Japanese, especially women, were sold as slaves.[3] Japanese slaves are believed to be the first of their nation to end up in Europe, and the Portuguese purchased large numbers of Japanese slave girls to bring to Portugal for sexual purposes, as noted by the Church in 1555. King Sebastian feared that it was having a negative effect on Catholic evangelization since the slave trade in Japanese was growing to larger proportions, so he commanded that it be banned in 1571[4][5]

Japanese slave women were even sold as concubines, serving on Portuguese ships and trading in Japan, mentioned by Luis Cerqueira, a Portuguese Jesuit, in a 1598 document.[6] Japanese slaves were brought by the Portuguese to Macau, where some of them not only ended up being enslaved to Portuguese, but as slaves to other slaves, with the Portuguese owning Malay and African slaves, who in turn owned Japanese slaves of their own.[7][8]

Hideyoshi was so disgusted that his own Japanese people were being sold en masse into slavery on Kyushu, that he wrote a letter to Jesuit Vice-Provincial Gaspar Coelho on 24 July 1587 to demand the Portuguese, Siamese (Thai), and Cambodians stop purchasing and enslaving Japanese and return Japanese slaves who ended up as far as India.[9][10][11] Hideyoshi blamed the Portuguese and Jesuits for this slave trade and banned Christian evangelization as a result.[12][self-published source][13]

Some Korean slaves were bought by the Portuguese and brought back to Portugal from Japan, where they had been among the tens of thousands of Korean prisoners of war transported to Japan during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98).[14][15] Historians pointed out that at the same time Hideyoshi expressed his indignation and outrage at the Portuguese trade in Japanese slaves, he himself was engaging in a mass slave trade of Korean prisoners of war in Japan.[16][17]

Fillippo Sassetti saw some Chinese and Japanese slaves in Lisbon among the large slave community in 1578.[18][19][20][21][22]

The Portuguese "highly regarded" Asian slaves like Chinese and Japanese, much more "than slaves from sub-Saharan Africa".[23] The Portuguese attributed qualities like intelligence and industriousness to Chinese and Japanese slaves which is why they favored them more.[24][25][26][27]

In 1595 a law was passed by Portugal banning the selling and buying of Chinese and Japanese slaves.[28]

17th century

When formal trade relations were established in 1609 by requests from Englishman William Adams, the Dutch were granted extensive trading rights and set up a Dutch East India Company trading outpost at Hirado. They traded exotic Asian goods such as spices, textiles, porcelain, and silk. When the Shimabara uprising of 1637 happened, in which Christian Japanese started a rebellion against the Tokugawa shogunate, it was crushed with the help of the Dutch. As a result, all Christian nations who gave aid to the rebels were expelled, leaving the Dutch the only commercial partner from the West. Among the expelled nations was Portugal who had a trading post in Nagasaki harbor on an artificial island called Dejima. In a move of the shogunate to take the Dutch trade away from the Hirado clan, the entire Dutch trading post was moved to Dejima.

19th century

Following the opening of Japan to trade with the west in the 1850s, the Shogun's government became more receptive to reestablishing diplomatic relations with the Portuguese government. On August 3, 1860, a commercial treaty was concluded between the two countries and diplomatic relations were established between them.[29]

20th century

In the course of the Second World War, both countries had a complicated relationship. While Portugal was a neutral power, it was aligned more closely with the Allies, although it tried to stick closely to strict neutrality in East Asia to protect its vulnerable territories of Macau and East Timor.

Macau was never under Japanese military occupation, causing it to become a center for refugees. However, in August 1943, Japanese troops seized a British steamer in the harbor of Macau and the next month, issued an ultimatum demanding the installation of Japanese advisors in the government, threatening direct military occupation. Portugal acceded to Japanese demands and Macau effectively became a Japanese protectorate. Upon discovering that Macau intended to sell aviation fuel to Japan, American forces launched several air raids on Macau throughout 1945. In 1950, the US government compensated the Portuguese government with US$20m for the air raid damage after a Portuguese government protest.[30]

East Timor was occupied in 1942 by the Allies after Portugal refused to cooperate with the Allies in the defense of Southeast Asia. In the Battle of Timor, the Japanese occupied East Timor, remaining in control until Japanese troops in East Timor surrendered to the Portuguese governor as part of the surrender of Japan.

Language

As a result of the Portuguese arrival to Japan, after a continuous influx of trade between Asia and Europe, Japanese vocabulary absorbed words of Portuguese origin as well as Portuguese of Japanese. Among its great part, these words mainly refer to products and customs that arrived through Portuguese traders.

Portuguese was the first Western language to have a Japanese dictionary, the Nippo Jisho (日葡辞書, Nippojisho) dictionary or "Vocabulário da Língua do Japão" ("Vocabulary of the Language of Japan" in old-fashioned orthography), compiled by Jesuits such as João Rodrigues, published in Nagasaki in 1603.

Resident diplomatic missions

-

Residence of the embassy of Japan in Lisbon

-

Embassy of Portugal in Tokyo

See also

- Arte da Lingoa de Iapam

- Christianity in Japan

- Hidden Christians of Japan

- History of Roman Catholicism in Japan

- A Ilha dos Amores

- List of Japanese words of Portuguese origin

- Medical School of Japan

- Nanban trade

- Nippo Jisho

- Tanegashima (Japanese matchlock)

References

- ^ HOFFMAN, MICHAEL (May 26, 2013). "The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ^ "Europeans had Japanese slaves, in case you didn't know…". Japan Probe. May 10, 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 2014-03-02.

- ^ "The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders". 26 May 2013.

- ^ Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4). Sophia University.: 463–492. JSTOR 25066328.

- ^ Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4): 463–492. JSTOR 25066328.

- ^ Michael Weiner, ed. (2004). Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorites (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 408. ISBN 0415208572. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Kwame Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates Jr, eds. (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 479. ISBN 0195170555. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0195337709. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4): 465. JSTOR 25066328.

- ^ Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa (2013). Religion in Japanese History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0231515092. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Donald Calman (2013). Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1134918430. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Gopal Kshetry (2008). FOREIGNERS IN JAPAN: A Historical Perspective. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1469102443. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ J F Moran, J. F. Moran (2012). Japanese and the Jesuits. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134881123. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Robert Gellately; Ben Kiernan, eds. (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 277. ISBN 0521527503. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Gavan McCormack (2001). Reflections on Modern Japanese History in the Context of the Concept of "genocide". Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. Harvard University, Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. p. 18. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Olof G. Lidin (2002). Tanegashima - The Arrival of Europe in Japan. Routledge. p. 170. ISBN 1135788715. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Amy Stanley (2012). Selling Women: Prostitution, Markets, and the Household in Early Modern Japan. Vol. 21 of Asia: Local Studies / Global Themes. Matthew H. Sommer. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520952386. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Jonathan D. Spence (1985). The memory palace of Matteo Ricci (illustrated, reprint ed.). Penguin Books. p. 208. ISBN 0140080988. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

countryside.16 Slaves were everywhere in Lisbon, according to the Florentine merchant Filippo Sassetti, who was also living in the city during 1578. Black slaves were the most numerous, but there were also a scattering of Chinese

- ^ José Roberto Teixeira Leite (1999). A China no Brasil: influências, marcas, ecos e sobrevivências chinesas na sociedade e na arte brasileiras (in Portuguese). UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. p. 19. ISBN 8526804367. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

Idéias e costumes da China podem ter-nos chegado também através de escravos chineses, de uns poucos dos quais sabe-se da presença no Brasil de começos do Setecentos.17 Mas não deve ter sido através desses raros infelizes que a influência chinesa nos atingiu, mesmo porque escravos chineses (e também japoneses) já existiam aos montes em Lisboa por volta de 1578, quando Filippo Sassetti visitou a cidade,18 apenas suplantados em número pelos africanos. Parece aliás que aos últimos cabia o trabalho pesado, ficando reservadas aos chins tarefas e funções mais amenas, inclusive a de em certos casos secretariar autoridades civis, religiosas e militares.

- ^ Jeanette Pinto (1992). Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510-1842. Himalaya Pub. House. p. 18. ISBN 9788170405870. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

ing Chinese as slaves, since they are found to be very loyal, intelligent and hard working' . . . their culinary bent was also evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Fillippo Sassetti, recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer (1968). Fidalgos in the Far East 1550-1770 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). 2, illustrated, reprint. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-638074-2. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

be very loyal, intelligent, and hard-working. Their culinary bent (not for nothing is Chinese cooking regarded as the Asiatic equivalent to French cooking in Europe) was evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Filipe Sassetti recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks. Dr. John Fryer, who gives us an interesting ...

- ^ José Roberto Teixeira Leite (1999). A China No Brasil: Influencias, Marcas, Ecos E Sobrevivencias Chinesas Na Sociedade E Na Arte Brasileiras (in Portuguese). UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. p. 19. ISBN 8526804367. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Paul Finkelman (1998). Paul Finkelman, Joseph Calder Miller (ed.). Macmillan encyclopedia of world slavery, Volume 2. Macmillan Reference USA, Simon & Schuster Macmillan. p. 737. ISBN 0028647815. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Duarte de Sande (2012). Derek Massarella (ed.). Japanese Travellers in Sixteenth-century Europe: A Dialogue Concerning the Mission of the Japanese Ambassadors to the Roman Curia (1590). Vol. 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1409472230. ISSN 0072-9396. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ A. C. de C. M. Saunders (1982). A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen in Portugal, 1441-1555. Vol. 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 0521231507. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Jeanette Pinto (1992). Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510-1842. Himalaya Pub. House. p. 18. ISBN 9788170405870. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Charles Ralph Boxer (1968). Fidalgos in the Far East 1550-1770 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford U.P. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-19-638074-2. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ Dias, Maria Suzette Fernandes (2007), Legacies of slavery: comparative perspectives, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 71, ISBN 978-1-84718-111-4

- ^ James Murdoch, A History of Japan, vol. 3, p. 662

- ^ Garrett, Richard J. Defences of Macau, The : Forts, Ships and Weapons over 450 years. ISBN 988-220-680-8. OCLC 1154841140.

External links

- Embassy of Portugal in Japan Archived 2020-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Embassy of Japan in Portugal (in Portuguese and Japanese)