Club-winged manakin

| Club-winged Manakin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male in NW Ecuador | |

| call recorded in Ecuador | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Pipridae |

| Genus: | Machaeropterus |

| Species: | M. deliciosus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Machaeropterus deliciosus (Sclater, PL, 1860)

| |

| |

The club-winged manakin (Machaeropterus deliciosus) is a small passerine bird which is a resident breeding species in the cloud forest on the western slopes of the Andes Mountains of Colombia and northwestern Ecuador. The manakins are a family (Pipridae) of small bird species of subtropical and tropical Central and South America.

Sound-making mechanism

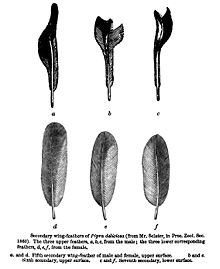

Like several other manakins, the club-winged manakin produces a mechanical sound with its extremely modified secondary remiges, an effect known as sonation.[4] The manakins adapted their wings in this odd way as a result of sexual selection.[2] In manakins, the males have evolved adaptations to suit the females' attraction towards sound. Wing sounds in various manakin lineages have evolved independently. Some species pop like a firecracker, and there are a couple that make whooshing noises in flight. The club-winged manakin has the unique ability to produce musical sounds with its wings.[5]

Each wing of the club-winged manakin has one feather with a series of at least seven ridges along its central vane. Next to the strangely ridged feather is another feather with a stiff, curved tip. When the bird raises its wings over its back, it shakes them back and forth over 100 times a second (hummingbirds typically flap their wings only 50 times a second). Each time it hits a ridge, the tip produces a sound. The tip strikes each ridge twice: once as the feathers collide, and once as they move apart again. This raking movement allows a wing to produce 14 sounds during each shake. By shaking its wings 100 times a second, the club-winged manakin can produce around 1,400 single sounds during that time.[5] In order to withstand the repeated beating of its wings together, the club-winged manakin has evolved solid wing bones (by comparison, the bones of most birds are hollow, making flight easier). The solid wing bones, a result of sexual selection, are also present in female manakins, who do not benefit from the trait.[6]

While this "spoon-and-washboard" anatomy is a well-known sound-producing apparatus in insects (see stridulation), it had not been well documented in vertebrates (some snakes stridulate too, but they do not have dedicated anatomical features for it).

References

- ^ BirdLife International (2018). "Machaeropterus deliciosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22701122A130270942. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22701122A130270942.en. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ a b Sclater, P. L. (1860). "List of Birds collected by Mr. Fraser in Ecuador, at Nanegal, Calacali, Perucho, and Puellaro, with notes and descriptions of new species". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 83–97.

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1871). The descent of man and selection in relation to sex. Vol. 2. London: John Murray. pp. 65–66.

- ^ Bostwick, Kimberly. "From Feathers, a Violin". BirdScope. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Archived from the original on 2006-09-12. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Zimmer, Carl (August 2, 2005). "A New Kind of Birdsong: Music on the Wing in the Forests of Ecuador". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- ^ "How beauty might have evolved for pleasure, not function". The Verge. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

External links

- ffrench, Richard; O'Neill, John Patton & Eckelberry, Don R. (1991): A guide to the birds of Trinidad and Tobago (2nd edition). Comstock Publishing, Ithaca, N.Y.. ISBN 0-8014-9792-2

- Hilty, Steven L. (2003): Birds of Venezuela. Christopher Helm, London. ISBN 0-7136-6418-5

- Stiles, F. Gary & Skutch, Alexander Frank (1989): A guide to the birds of Costa Rica. Comistock, Ithaca.

- Bio One

- 2005-07-25 Cornell University News Service Rare South American bird 'sings' with its feathers to attract a mate, Cornell researcher finds

- Bird "Sings" Through Feathers on National Geographic