Flor Silvestre

Guillermina "Flor Silvestre" Jiménez Chabolla | |

|---|---|

| File:Flor Silvestre in Ánimas Trujano.jpg Silvestre in Ánimas Trujano (1962) | |

| Born | Guillermina Jiménez Chabolla 16 August 1930 |

| Died | 25 November 2020 (aged 90) Villanueva, Zacatecas, Mexico |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1943–2020 |

| Spouse(s) | Andrés Nieto |

| Children | Dalia Inés Francisco Rubiales Marcela Rubiales Antonio Aguilar, hijo Pepe Aguilar |

| Relatives | La Prieta Linda (sister) Mary Jiménez (sister) Majo Aguilar (granddaughter) Leonardo Aguilar (grandson) Ángela Aguilar (granddaughter) |

| Awards | Eduardo Arozamena Medal |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals guitar |

| Labels | |

| Website | florsilvestreoficial.com |

| Signature | |

| |

Guillermina Jiménez Chabolla (16 August 1930 – 25 November 2020)[1] known professionally as Flor Silvestre, was a Mexican singer and actress.[2] She was one of the most prominent and successful performers of Mexican and Latin American music,[3] and was a star of classic Mexican films during the Golden Age of Mexican cinema. Her more than 70-year career[4] included stage productions, radio programs, records, films, television programs, comics and rodeo shows.

Famed for her melodious voice and unique singing style, hence the nicknames "La Sentimental" ("The Sentimental One") and "La Voz Que Acaricia" ("The Voice That Caresses"), Flor Silvestre was a notable interpreter of the ranchera, bolero, bolero ranchero, and huapango genres. She recorded more than 300 songs for three labels: Columbia, RCA Víctor, and Musart. In 1945, she was announced as the "Alma de la Canción Ranchera" ("Soul of Ranchera Song"),[5] and in 1950, the year in which she emerged as a radio star, she was proclaimed the "Reina de la Canción Mexicana" ("Queen of Mexican Song").[6] In 1950, she signed a contract with Columbia Records and recorded her first hits, which include "Imposible olvidarte", "Que Dios te perdone", "Pobre corazón", "Viejo nopal", "Guadalajara", and "Adoro a mi tierra". In 1957, she began recording for Musart Records and became one of the label's exclusive artists with numerous best-selling singles, such as "Cielo rojo", "Renunciación", "Gracias", "Cariño santo", "Mi destino fue quererte", "Mi casita de paja", "Toda una vida", "Amar y vivir", "Gaviota traidora", "El mar y la esperanza", "Celosa", "Vámonos", "Cachito de mi vida", "Miel amarga", "Perdámonos", "Tres días", "No vuelvo a amar", "Las noches las hago días", "Estrellita marinera", and "La basurita", among others. Many of her hits charted on Cashbox Mexico's Best Sellers and Record World Latin American Single Hit Parade.[7] She also participated in her husband Antonio Aguilar's musical rodeo shows.

Flor Silvestre appeared in more than seventy films between 1950 and 1990. Beautiful and statuesque, she became one of the leading stars of the "golden age" of the Mexican film industry. She made her acting debut in the film Primero soy mexicano (1950), directed by and co-starring Joaquín Pardavé. She played opposite famous comedians, such as Cantinflas in El bolero de Raquel (1957). Director Ismael Rodríguez gave her important roles in La cucaracha (1959), and Ánimas Trujano (1962), which was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[8] She was also the star of the comic book La Llanera Vengadora.[9] In 2013, the Association of Mexican Cinema Journalists honored her with the Special Silver Goddess Award.

Silvestre died on 25 November 2020 at her home in Villanueva, Zacatecas.[10][11]

Life and career

1920–1938: Childhood

Flor Silvestre was born Guillermina Jiménez Chabolla on 16 August 1920 in Salamanca, Guanajuato, Mexico.[1] She was the third child and second daughter of Jesús Jiménez Cervantes, a butcher,[12] and María de Jesús Chabolla Peña (1906 – 5 September 1993).[13] Her father owned and ran a meat shop in Salamanca.[12] Her older siblings are Francisco "Pancho" and Raquel, and her younger siblings are Enriqueta "La Prieta Linda", José Luis, María de la Luz "Mary", and Arturo. Enriqueta and María de la Luz also became singers. Her maternal grandparents were Felipe Chabolla and Inés Peña.[13]

Guillermina was raised in Salamanca and began singing at an early age. Her parents, who were also fond of singing, encouraged her to sing.[12] She loved the mariachi music of famous Mexican singers Jorge Negrete and Lucha Reyes,[12] and also sang songs that belonged to the pasodoble, tango, and bolero genres, which were popular in Mexico in the late 1930s.[12] Her interest in singing and acting led her to participate in Christmas pageants, school plays, and local festivals.[14]

Her mother, who wanted to live in Mexico City, urged her father to sell all their property in Salmanca and relocate the family to the Mexican capital.[12] María de Jesús took her three youngest children with her to Mexico City, leaving the oldest four (including Guillermina) in Salamanca in the care of her sisters, who were nuns.[12] Guillermina completed primary school in Salamanca before reuniting with her family in Mexico City.[15] In Mexico City, her parents enrolled her in the Escuela Bancaria Comercial Milton on Madero Avenue,[15] where she took secretarial classes.[16]

1943–1949: Early stage and radio success

Guillermina Jiménez (Flor Silvestre) began her singing career in 1943, when she was 23 years old. She and her father attended a performance of the famous Mariachi Pulido at the Teatro del Pueblo, a theater located in the Abelardo L. Rodríguez Market in central Mexico City. After the performance was over, she got up on stage and told the stage director that she wanted to sing.[15][12] The Mariachi Pulido's director refused to accompany her, stating that they did not collaborate with amateurs,[15] but the stage director, Carlos López Santillán, told her that he would let her sing the following week and promised to hire a mariachi from the Tenampa bar to perform with her.[15] On the day of her debut, wearing a traditional Mexican blouse and skirt her mother had made for her,[12] she sang three popular songs, "La canción mexicana", "Yo también soy mexicana", and "El herradero".[15] Her performance was a great success and she received an ovation from the audience.[15]

Her next performance at the Teatro del Pueblo was in the play La soldadera, directed by López Santillán,[17] in which she played a girl who comes out of a railway wagon and sings "La soldadera", a song written for her by José de Jesús Morales. The play was also broadcast by Mexico's national radio station, XEFO,[12] and "La soldadera" became the first song she performed on radio. The title of the song, which is Spanish for "the female soldier", also became her first stage name until it was claimed by another singer.[15] Arturo Blancas, an Excélsior journalist and XEFO announcer, thought she looked more "like a flower" than a soldier and suggested she change her stage name to La Amapola, which means "the poppy".[15] However, this stage name was also claimed by another woman, the sister of singer La Panchita.[15] Blancas then chose the title of Dolores del Río's 1943 drama film as the young singer's new stage name, and Guillermina Jiménez became Flor Silvestre, which means "wild flower".[15]

Under her new stage name, Flor Silvestre won first place in an amateur contest sponsored by Mexico's most popular radio station, XEW, known as "the voice of Latin America from Mexico".[15] Her participation in the contest earned her a contract to sing in revues at the Teatro Colonial, located on San Juan de Letrán Avenue (now Eje Central).[15][12] The Teatro Colonial was "Mexico's most popular [theater]" in the 1940s,[18] and Flor Silvestre's performances there were noticed by a showman who hired her as part of his touring company.[12] The showman and his company toured Torreón, in northern Mexico, where Flor Silvestre was the opening act of the touring company's headliner, the famous Argentine tango singer Hugo del Carril.[12] Flor Silvestre's family was experiencing financial problems at the time, and she sang at banquets and other places in order to win more money and help her parents.[12]

In December 1945, Flor Silvestre performed at Guadalajara's Coliseo Olímpico and was announced as "Flor Silvestre, the Soul of Ranchera Song". In November 1946, she was invited to perform at the inauguration of Guadalajara's Juárez movie theater. The Guadalajara newspaper El Informador described her as "Flor Silvestre, young XEW singer, who represents the feeling of our land within the ranchera song".[19] Between 1947 and 1949, Flor Silvestre and the showman's company toured Central and South America, performing at the best nightclubs along the way.[12] Hugo del Carril presented Flor Silvestre to audiences when the company toured Argentina.[20] The company eventually made its way to Peru, where they performed for the Mexican Air Force, before returning to Mexico.[12]

1950–1952: Acting debut and first records

When Flor Silvestre returned to Mexico from her South American tour in 1950, her manager got her a contract to perform at Mexico City's most popular nightclub, El Patio.[12] She later said: "Emilio Azcárraga and Gregorio Walerstein went there every day, and everyone saw me there, and they all hired me without me asking for anything, and everyone called me and called me, and that's how I started [singing] on the XEW [station]".[21] Azcárraga, the owner of XEW, Mexico's top station, gave her her first radio program, Increíble pero cierto, which she also hosted. Walerstein, a leading film producer known as "the Tsar of Mexican films", signed her to a five-film contract.[12]

With the success of her radio program, her singing career began to ascend. Journalist Mónica Fio wrote in her column "Micrófono":

We unreservedly commend the young singer "Flor Silvestre" because her radio career, though rapid, is made on the basis of effort, perseverance, and study. Whenever we hear her programs we confirm that she does not abandon herself to brief and easy successes, but seeks to improve herself. This is how one reaches the goal. This is how one creates prestige. This is how one triumphs.[22]

Flor Silvestre made her first records in 1950 for Columbia Records' Mexican branch. She recorded at least twelve songs for the label, one on each side of six 78 rpm singles. These songs also became her first hits. "Imposible olvidarte", "Que Dios te perdone", "Pobre corazón", "Viejo nopal", "Guadalajara", and "Mi amigo el viento" were recorded with Gilberto Parra's mariachi. "Siempre el amor", "Con un polvo y otro polvo", "Adoro a mi tierra", "La presentida", "Llorar amargo", and "Oye, morena"[23] were recorded with Rubén Fuentes' mariachi. After recording her first singles, Flor Silvestre formed a duet named Las Flores with her then-unknown sister La Prieta Linda; they recorded two songs—"Los desvelados"[24] and "Lo traigo en la sangre"[25] (with Rubén Fuentes' mariachi)—for Columbia.

In February 1950, she was a part of the "numerous, hybrid, but useful cast" of ¡A los toros!, a revue about bullfighting staged at the Teatro Tívoli.[26] It was written and presented by announcer Paco Malgesto, who would become her second husband.[26] In the revue, she sang Mexican musical numbers associated with bullfights.[26]

Although Flor Silvestre had made her film debut in 1949 singing in Te besaré en la boca (released in 1950),[27] she was given her first leading role in the Walerstein production Primero soy mexicano (1950), co-starring Joaquín Pardavé (who also wrote and directed the film) and Luis Aguilar and featuring Francisco "Charro" Avitia.[28]

She was reunited with her Primero soy mexicano co-stars Luis Aguilar and Francisco Avitia in the film El tigre enmascarado, which premiered in 1951. She then appeared as the leading lady of actor Dagoberto Rodríguez in a film trilogy, El lobo solitario, La justicia del lobo, and Vuelve el lobo (all released in 1952).

1955–1957: Return to films and television debut

In early 1955, Flor Silvestre sang on the XEW radio program Su programa Calmex, sponsored by Calmex Sardines.[29] Other entertainers on the program included Miguel Aceves Mejía, the Trío Tariácuri, and the Hermanitas de Alba.

In 1955, she also appeared in her first color film, La doncella de piedra, one of the first Mexican CinemaScope productions.[30] An adaptation of Rómulo Gallegos' novel Sobre la misma tierra, the film features Flor Silvestre in the role of Cantaralia Barroso, the mother of the novel's protagonist, Remota Montiel (played by Elsa Aguirre).

Flor Silvestre had one of the starring roles in the stage play La hacienda de Carrillo, a revue which opened on 1 July 1955 at the new Teatro Ideal.[31] Written by Carlos M. Ortega and Pablo Prida, the play was about "a hacienda in the interior [of the country], whose owner leaves his land to embrace politics, become a deputy, and come to the metropolis in the company of his daughters".[31] Theater critic Armando de María y Campos wrote that the cast included "the radio singer Guillermina Jiménez de Rubiales, better known as Flor Silvestre, very beautiful and young too, and also very tender as a vedette".[31] That same month, Flor Silvestre, Agustín Lara, Pedro Vargas, Rosa de Castilla, and others provided musical performances for the film La virtud desnuda (released in 1957), a Calderón Films production starring Columba Domínguez.[32]

Her first film co-starring Antonio Aguilar, her future husband, was La huella del chacal. That same year she played a swarthy maid named Liliana in Rapto al sol, a color film shot in Nicaragua.[33]

In 1957, RCA Victor released her first recording of "Cielo rojo", which would become one of her signature songs. The single, which included "¡Qué padre es la vida!" on side B, became a hit. On Mother's Day 1957, she made her television debut with a successful performance in the television play Secreto de familia, with Sara García and Miguel Arenas.[34] One of her famous roles was as Leonor, the mother of Cantinflas' godson, in the popular Eastmancolor comedy El bolero de Raquel (1957).

1958–1963: First recordings for Musart Records and Ánimas Trujano

She received top billing for the first time in Pueblo en armas (1959) and its sequel ¡Viva la soldadera! (1960), both directed by Miguel Contreras Torres.

She had a supporting role opposite María Félix in Ismael Rodríguez's Mexican Revolution epic La cucaracha (1959). She also recorded "Te he de querer", "La chancla", and "La Valentina" for the film's soundtrack album, La cucaracha: Música de la película, released by Musart Records.[35]

Flor Silvestre, her first Musart album, was released around 1958. It includes her early Musart hits, such as "El ramalazo", "¡Qué bonito amor!", "La flor de la canela", "Échame a mí la culpa", "Ay el amor", "Lágrimas del alma", and "Amémonos".[citation needed]

In 1960, she starred opposite the popular comedy duo Viruta and Capulina in Dos locos en escena.[citation needed]

In 1961, she rerecorded "Cielo rojo" for Musart, accompanied by Pepe Villa's Mariachi México. This second version also became a success and is the first track of her second Musart album, Flor Silvestre con el Mariachi México. The album also includes her early 1960s hits, "Pa' todo el año", "Renunciación", "Desolación", "El peor de los caminos", "Aquel inmenso amor", and "Para morir iguales".[citation needed]

One of her major roles was as Catalina, the beautiful, sensuous flirt, in the Oscar-nominated, Golden Globe-winning drama film Ánimas Trujano (1962), co-starring Toshiro Mifune and Columba Domínguez. This was her second collaboration with film director Ismael Rodríguez after her supporting role in La cucaracha.[citation needed]

1964–1969: Multiple albums

In early 1964, she released her third Musart album, Flor Silvestre con el Mariachi México, vol. 2, which includes her hits "Gracias", "Perdí la partida", "Bendición de Dios", "Árboles viejos", "Te digo adiós", "Un jarrito", "Quédate esta vez", and "Plegaria". Her fourth Musart album, La sentimental (1964), includes both ranchera and bolero songs. It is her first album without mariachi arrangements; Benjamín "Chamín" Correa is credited as the album's guitarist. La sentimental peaked at number 9 on Record World Latin American LP Hit Parade.[36] "Mi destino fue quererte" peaked at number 4 on Record World Latin American Single Hit Parade[37] and became one of Flor Silvestre's signature songs. In December 1964, Cashbox ranked her among the top ten Mexican folk singers of the year.[38]

Her fifth Musart album, La acariciante voz de Flor Silvestre, was released in 1965. One of the album's singles, "Una limosna", topped the Record World Latin American Single Hit Parade chart.[39] The album also includes her hits "Gaviota traidora", "El mar y la esperanza", "Amor se escribe con llanto", and "Espumas".

Celosa con Flor Silvestre y otros éxitos (1966), her sixth studio album for Musart Records, peaked at number 11 on Record World Latin American LP Hit Parade.[40] The album's lead single, "Celosa", peaked at number 9 on Cashbox Mexico's Best Sellers[41] and number 4 on Record World Latin American Single Hit Parade.[42] "¿Por qué, Dios mío?", another single included in Celosa, also charted well on Record World Latin American Single Hit Parade.[43]

In 1967, she released two albums, Boleros rancheros con la acariciante voz de Flor Silvestre and Flor Silvestre, vol. 6, and made her last film of the decade, El as de oros.

In 1968, she released two albums, Flor Silvestre, vol. 7 and Flor Silvestre, vol. 8. Flor Silvestre, vol. 7 includes "Reconciliación", one of her major hits from the late 1960s, as well as several other hits, including "Cenizas de amor", "Cariño malo", "Triunfamos", and "Tres días". Flor Silvestre, vol. 8 features arrangements by famous guitarist Antonio Bribiesca[44] and composer Gustavo A. Santiago and includes the hits "No vuelvo a amar" and "Tú, sólo tú".

1970–1989: Final films and multiple musical genres

In 1970, she released her album Amor, siempre amor,[45] accompanied by the Mariachi Guadalajara. The album features innovative mariachi, piano, harmonica, and steel (Hawaiian) guitar arrangements in its songs. Its first track, "La cruz de lo imposible", is songwriter Lupita Ramos' first work.[46] This was Flor Silvestre and Ramos' first collaboration; Ramos went on to author several other songs for Flor Silvestre. Another notable track is "La mitad de mi orgullo", by José Alfredo Jiménez.

In the early 1970s, she recorded her first bolero album, Y las canciones de sus tríos favoritos. The album features cover versions of popular boleros from the 1950s, including "Un siglo de ausencia", "Condición", "El reloj", and "La barca". Cashbox included the album in its Latin Picks section and described it as "a masterpiece for lovers of Latin boleros".[47] It was later rereleased as Sus canciones favoritas con... Flor Silvestre (LP reissue) and Mis boleros favoritos (CD reissue).

In 1972, she released three albums: Una gran intérprete y dos grandes compositores, a tribute to songwriters Cornelio Reyna and Ferrusquilla; La voz que acaricia, which includes her hits "Solo con las estrellas" and "Hastío"; and Canciones con alma, her second album of bolero songs. She sang two tracks from Una gran intérprete y dos grandes compositores in the two films she made that year; she sang "Tema eterno" in La yegua colorada and "No me lo tomes a mal" in Valente Quintero. Billboard included Canciones con alma in its Top Album Picks section and wrote, "A good solid LP overall of love ballads. Best cuts: 'Vuelve', 'Tormento', 'Quisiera'".[48]

In 1973, she played one of Pancho Villa's lovers in La muerte de Pancho Villa and released her first norteño album, La onda norteña de Flor Silvestre. The album's cover is a photograph of her as the character in the film. She also played Felipe Carrillo Puerto's wife, Isabel Palma, in the film Peregrina (released in 1974), in which she sang the Guty Cárdenas bolero "Quisiera".

In 1974, she released her album Con todo mi amor a mi lindo Puerto Rico,[49] which is a tribute to two famous Puerto Rican songwriters, Rafael Hernández and Pedro Flores. For this album she recorded four Hernández songs, "Campanitas de cristal", "Inconsolable", "No me quieras tanto", and "Silencio", and three Flores songs, "Obsesión", "Amor", and "Esperanza inútil". The album also includes "Cruz de olvido", one of her hits, and "Vuelve pronto", a Spanish-language version of "Paper Roses". The album's release coincided with her appearance in the film Mi aventura en Puerto Rico, in which she sang "Desvelo de amor" and "Obsesión". This same year she appeared on the film Peregrina.[50]

She sang "La palma" in Simón Blanco (1975) and played the female leads in Don Herculano enamorado (1975), El moro de cumpas (1977), and Mi caballo el cantador (1979).

In 1978, she released her album Ahora sí va en serio, which includes several songs written by Joan Sebastian. The title track was included in the Cashbox Latin Singles to Watch list.[51] Other Sebastian songs included in the album are "Levantado en armas", "Te regalo mi pena", and "Trono caído".

In 1979, Cashbox included her single "Morir al lado de mi amor" in its Latin Singles to Watch list.[52]

1989–2020: Banda albums and tributes

In 1989, she recorded banda music for the first time. She told the press, "I was very afraid to record with a tambora; I thought it was too much sound, a lot of equipment, but when I recorded I loved it, I felt happy, and more because it was the band of Don Ramón López Alvarado. We recorded 'Los mirasoles', 'La rama', and 'Quiero que sepas'".[53]

She made her final film, Triste recuerdo, in 1990. In 1991, she recorded her first banda album, Flor Silvestre con tambora, which includes a banda version of one of her bolero hits, "Caricia y herida".

In 1994, she released her album Me regalo contigo, which includes a song dedicated to her marriage with Aguilar, "Para siempre juntos", and a vallenato song, "Sólo para ti".

In 2001, she released her second banda album, Flor Silvestre con tambora, which includes new versions of her 1960s hits "Cariño santo", "Celosa", "Desolación", "Mi destino fue quererte", and "El mar y la esperanza".

On 21 December 2010, she released her most recent album, Soledad: canto a mi amado y a su recuerdo, which she dedicated to her late husband.[54] The album features interesting songs she had never recorded before, such as "Soledad", "Y llegaste tú", "El andariego", "Luz de luna", "Amanecí en tus brazos", "Las ciudades", "Los ejes de mi carreta", and "Sombras".

On 9 March 2015, her documentary Flor Silvestre: su destino fue querer premiered at Zapopan's Plaza de las Américas as part of the Guadalajara International Film Festival.[55][56] The 24-minute documentary features interviews with Flor Silvestre, who recounts her life and career; her five children, Dalia, Francisco, Marcela, Antonio, and Pepe; and singers Angélica María and Guadalupe Pineda.

In 2016, she was featured on "Para morir iguales", a track of her son Antonio's most recent album, Caballo viejo.[57]

Personal life

Flor Silvestre married her first husband, Andrés Nieto,[58] in the 1940s. She gave birth to her first child, singer and dancer Dalia Inés Nieto, when she was 17 years old.[59]

Around 1953, Flor Silvestre married radio announcer and bullfighting chronicler Francisco Rubiales Calvo "Paco Malgesto" (1914–1978), who would later become a famous presenter and pioneer of Mexican television.[60] They had two children, translator Francisco Rubiales and singer and actress Marcela Rubiales.[59] They lived in a house in Mexico City's Lindavista neighborhood.[61] The couple separated and began divorce proceedings in 1958.[62]

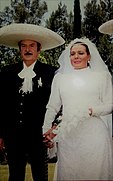

Flor Silvestre's third and last husband was singer and actor Antonio Aguilar, who died in 2007. He was the love of her life. They first met in 1950 when he was invited to sing on her program Increíble pero cierto at the Verde y Oro studio of radio station XEW in Mexico City. In 1955, they made their first film together, La huella del chacal, but their relationship began when they made the film El rayo de Sinaloa in 1957. They married in 1959 (or 1960, according to some sources) and had two sons who also became singers and actors, Antonio "Toño" Aguilar and José "Pepe" Aguilar. Aguilar built her a spacious home and ranch, El Soyate, northeast of Tayahua, Zacatecas.

On 28 February 2012, Flor Silvestre underwent surgery to extirpate the cancer-stricken half of her right lung.[63] She responded well to the surgery.[64]

Death

Flor Silvestre died on 25 November 2020, on her estate in "El Soyate" Villanueva, Zacatecas, Mexico.[65][66] She died of natural causes.

Awards and honors

Flor Silvestre received many awards and honors throughout her career. She has her handprints in the Plaza de las Estrellas[67] (the Mexican equivalent of the Hollywood Walk of Fame).

- In 1966, Musart Records awarded her The Golden Clover (known as Trébol de Oro in Spanish) for being one of the label's best-selling artists in 1965.

- In 1970, Musart Records awarded her another Golden Clover for being one of the label's best-selling artists in 1969.[68]

- In 1972, she won the Record World Award for Best Mexican Actress-Singer.[69]

- In 2001, the National Association of Actors awarded her the Eduardo Arozamena Medal for her 50-year career.[70]

- In 2008, she was the grand marshal of the Comité Mexicano Cívico Patriótico's Mexican Independence Parade in Los Angeles, California.[71]

- In 2010, the twenty-first edition of the World Mariachi Day (Día Mundial del Mariachi) awarded her the Pedro Infante Medal for her "outstanding work and dissemination of Mexican music".[72]

- In 2012, the Confederation of Livestock Organizations awarded her a "bull sculpture" for her contribution to Mexican culture.[73]

- In 2013, the Association of Mexican Cinema Journalists awarded her the Special Silver Goddess for her career.[74] Mexican actor Ignacio López Tarso presented her with the award and said: "For me it is a great honor and personal satisfaction to give you this award, to a great figure of Mexican cinema who, either walking or on horseback, made the best movies of the Mexican film industry".[74]

- In 2014, the Government of the State of Zacatecas paid tribute to her career and gave her a special accolade at the Teatro Calderón in the state capital as part of the First Corrido Festival.[75]

- In 2015, while promoting the release of her documentary entitled Flor Silvestre: Su destino fue querer, she was honored in Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco;[76] Los Angeles, California;[77] and Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes.[78]

Discography

Flor Silvestre made her first recordings in 1950 for the Mexican Columbia label (Discos Columbia de México). In these recording sessions, she was backed up by the mariachis of Gilberto Parra and Rubén Fuentes. Ten of these recordings, which were originally released on 78 rpm singles, were included in the greatest hits album Flor Silvestre canta sus éxitos, released in 1964 by Columbia's subsidiary label Okeh. This compilation album was later remastered and reissued in digital format by Sony Music Entertainment México in 2016.

Flor Silvestre also recorded some songs for the RCA Víctor label in 1957. For this label, she recorded a single containing her first version of "Cielo rojo" on side A and "Qué padre es la vida" on side B.

In 1957, Flor Silvestre signed a contract with the Musart label. Among her first recordings for Musart are the songs "Nuestro gran amor" and "Pajarillo de la sierra", included in the soundtrack album of the Heraclio Bernal films, and "Te he de querer", "La chancla", and "La Valentina", included in the soundtrack album for the film La cucaracha. In 1958, she released her first studio album for Musart, Flor Silvestre. Musart has more than 300 of Flor Silvestre's recordings, many of them available in digital format since 2008.

Singles

Her hit singles include:

- "Imposible olvidarte" / "Que Dios te perdone (Dolor de ausencia)" (1950)

- "Pobre corazón" / "Viejo nopal" (1950)

- "Guadalajara" / "Mi amigo el viento" (1950)

- "Siempre el amor" / "Con un polvo y otro polvo" (1950)

- "Adoro a mi tierra" / "La presentida" (1950)

- "Llorar amargo" / "Oye, morena" (1950)

- "Cielo rojo" / "Qué padre es la vida" (1957)

- "Ay! el amor" / "El ramalazo" (1959)

- "Mi destino fue quererte" / "Viejo nopal" (1964)

- "Gaviota traidora" / "La puerta blanca" (1964)

- "Celosa" / "Te necesito" (1966)

- "El despertar" / "Miel amarga" (1967)

- "Perdámonos" / "El patito feo" (1967)

- "No vuelvo a amar" / "No es tan fácil" (1968)

- "Sin mentira ni traición" / "Las noches las hago días" (1971)

- "El tiempo que te quede libre" / "Seis años" (1972)

- "La basurita" / "Nuestra tumba" (1976)

Studio albums

- Flor Silvestre (1959)

- Flor Silvestre con el Mariachi México (1963)

- Flor Silvestre con el Mariachi México, vol. 2 (1964)

- La sentimental Flor Silvestre (1964)

- La acariciante voz de Flor Silvestre (1965)

- Celosa con Flor Silvestre y otros éxitos (1966)

- Boleros rancheros con la acariciante voz de Flor Silvestre (1967)

- Flor Silvestre, vol. 6 (1967)

- Flor Silvestre, vol. 7 (1968)

- Flor Silvestre, vol. 8 (1968)

- Amor, siempre amor (1970)

- Flor Silvestre y las canciones de sus tríos favoritos (1970)

- Las noches las hago días (1971)

- Una gran intérprete y dos grandes compositores (1972)

- La voz que acaricia (1972)

- Canciones con alma (1972)

- La onda norteña (1973)

- Aquella (1974)

- Con todo mi amor a mi lindo Puerto Rico (1974)

- Y yo (1975)

- La basurita (1976)

- Arrullo de Dios (1977)

- Ahora sí va en serio (1978)

- Con otra lumbre (1981)

- Flor Silvestre cantando norteño (1984)

- No te pido más (1988)

- 15 exitos con banda, vo. 1 (1989)

- Flor Silvestre con tambora (1991)

- Me regalo contigo (1993)

- Soledad: canto a mi amado y a su recuerdo (2010)

Extended plays

- Para morir iguales

- Desolación

- Volver a verte

- Mi destino fue quererte

- Aquel amor

- Vámonos

- Celosa

- Una limosna

- Miel amarga

- Perdámonos

Compilation albums

- Flor Silvestre canta sus éxitos (1964)

- Los éxitos de Flor Silvestre (1972)

- El disco de oro de Flor Silvestre (1977)

- 15 éxitos (1984)

- 15 éxitos, vol. 2 (1989)

- 15 grandes éxitos (1998)

- Colección de oro: Flor Silvestre con mariachi (2003)

- Mexicanísimo: Flor Silvestre (2015)

- Serie del recuerdo 2 en 1: Flor Silvestre (2016)

- Mi México querido (2020)

Selected filmography

Flor Silvestre appeared in more than seventy films, almost always as the star and sometimes as a supporting actress or musical guest. Her film career spanned several genres, including ranchera comedy, rural drama, Mexican western, horror film, urban comedy, and Mexican Revolution drama. She starred in the following Mexican classics:

- Primero soy mexicano (1950)

- El tigre enmascarado (1951)

- El lobo solitario (1952)

- La justicia del lobo (1952)

- Vuelve el lobo (1952)

- La huella del chacal (1956)

- Rapto al sol (1956)

- El bolero de Raquel (1957)

- El jinete sin cabeza (1957)

- La justicia del gavilán vengador (1957)

- La cabeza de Pancho Villa (1957)

- Los muertos no hablan (1958)

- ¡Paso a la juventud..! (1958)

- Mi mujer necesita marido (1959)

- Kermesse (1959)

- Tan bueno el giro como el colorado (1959)

- Pueblo en armas (1959)

- El hombre del alazán (1959)

- La Cucaracha (1959)

- Escuela de verano (1959)

- ¡Quietos todos! (1959)

- El gran pillo (1960)

- Dos locos en escena (1960)

- Las hermanas Karambazo (1960)

- Poker de reinas (1960)

- Las tres coquetonas (1960)

- Vivo o muerto (1960)

- De tal palo tal astilla (1960)

- Los fanfarrones (1960)

- ¡Viva la soldadera! (1960)

- Luciano Romero (1960)

- Juan sin miedo (1961)

- Ánimas Trujano (1962)

- La venganza de la sombra (1962)

- La trampa mortal (1962)

- Aquí está tu enamorado (1963)

- Tres muchachas de Jalisco (1964)

- El revólver sangriento (1964)

- Escuela para solteras (1965)

- El rifle implacable (1965)

- Alma llanera (1965)

- El tragabalas (1966)

- El alazán y el rosillo (1966)

- Caballo prieto azabache (1968)

- El as de oros (1968)

- Lauro Puñales (1969)

- El ojo de vidrio (1969)

- Vuelve el ojo de vidrio (1970)

References

- ^ a b "Guillermina Jimenez-chabolla, "United States, Border Crossings from Mexico to United States, 1903-1957"". FamilySearch. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Festival star also a gourmet cook". Arizona Republic. 1 September 1976. p. 98. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

Flor Silvestre is a talented equestrienne, actress and singer.

- ^ "Native and Foreign Stars Score With Audiences". Billboard. 16 December 1967. p. M-14. Retrieved 9 September 2016.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre recibe Diosa de Plata especial por su trayectoria". El Informador. 31 July 2013. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Coliseo Olímpico: Viernes 14 de diciembre de 1945, Grandioso Debut de: El Chino Herrera Con la Gran Compañía de Revistas y Atracciones en la que figuran:... Flor Silvestre Alma de la Canción Ranchera". El Informador. 12 December 1945. p. 6.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre: Reina de la Canción Mexicana. Estrella de Cine". El Informador. 25 July 1950. p. 6.

- ^ "Latin American Single Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 21 May 1966. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- ^ "The 34th Academy Awards (1962)". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

- ^ "An International Catalogue of Superheroes". Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ "Muere la cantante Flor Silvestre, mamá de Pepe Aguilar". Univision. November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Murió la actriz y cantante Flor Silvestre". Milenio. November 25, 2020. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Entrevista Lic. Esparza con Flor Silvestre". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 30 March 2017.

- ^ a b "Maria de Jesus Chabolla Pena Mexico, Distrito Federal, Civil Registration, 1832-2005". FamilySearch. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Liner notes by Raúl Vieyra for the album Flor Silvestre, vol. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Kühne, Cecilia (23 October 2003). "Una flor que comenzó cantando". Imagen. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "El amor entre las Estrellas Hispanas: FLOR SILVESTRE Y TONI AGUILAR SE AMAN". Observador. 5 March 1965. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Merlín, Socorro (1995). Vida y milagros de las carpas: la carpa en México, 1930-1950. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. p. 148. ISBN 9789682982552.

- ^ de Maria y Campos, Armando. "Breve historia del teatro Colonial". Reseña histórica del teatro en México. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ "Se Inauguró Solemnemente el Teatro "Juárez": El C. Gobernador del Estado pronunció unas palabras – Asistieron artistas de México". El Informador. 22 November 1946.

- ^ Liner notes by Raúl Vieyra from the album Flor Silvestre, vol. 6 (1967).

- ^ "Flor Silvestre estrena documental en Guadalajara". Vanguardia. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Fio, Mónica (9 April 1950). "Micrófono: "Flor Silvestre"". El Siglo de Torreón. Retrieved 16 January 2015.

- ^ "Novedades de esta Semana y de más Exito". El Siglo de Torreón. 8 July 1951. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Los Desvelados by Dueto Las Flores". The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Lo Traigo En La Sangre by Dueto Las Flores". The Strachwitz Frontera Collection of Mexican and Mexican American Recordings. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ a b c de María y Campos, Armando. "Inauguración de una nueva temporada frívola en el Tívoli. Estreno de la revista ¡A los toros!. Los ases taurinos del momento sube a la escena reclamados por el público". Reseña histórica del teatro en México. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ García Riera, Emilio (1992). Historia documental del cine mexicano: 1949-1950. Universidad de Guadalajara. p. 151. ISBN 9688954284.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre, estandarte de la música ranchera". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ^ "Advertisement for Su programa Calmex". El Siglo de Torreón. 2 January 1955. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Garcia Riera, Emilio; Macotela, Fernando (1984). La guía del cine mexicano de la pantalla grande a la televisión, 1919-1984. Editorial Patria. p. 104. ISBN 9683900291.

- ^ a b c de María y Campos, Armando (14 July 1955). "Con la inauguración del teatro Ideal vuelven las revistas mexicanas". Novedades. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Vargas, Pedro; Garmabella, José Ramón (1985). Pedro Vargas: "una vez nada maś". Ediciones de Comunicación. p. 224. ISBN 9687037172.

- ^ Cortés, María Lourdes (2007). La pantalla rota: cien años de cine en Centroamérica. Fondo Editorial Casa de las Américas. p. 198. ISBN 978-9592602083.

- ^ "El Cine en México: Flor Silvestre Artista de Cine y TV". El Siglo de Torreón. 9 June 1957. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ "Liner notes for the album La cucaracha: Música de la pelicula". Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ "Latin American LP Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 23 April 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Latin American Single Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 30 April 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Mexico – Review 1964" (PDF). Cashbox. 26 December 1964. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Latin American Single Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 21 May 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Latin American LP Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 3 September 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Mexico's Best Sellers" (PDF). Record World. 9 April 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Latin American Single Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 30 July 1966. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Latin American Single Hit Parade" (PDF). Record World. 29 April 1967. Retrieved 25 March 2017.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre con la guitarra de A. Bribiesca" (PDF). Record World. 29 March 1969. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre "Amor Siempre Amor"" (PDF). Record World. 4 July 1970. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Biografía de Lupita Ramos". Sociedad de Autores y Compositores de México (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Latin Picks" (PDF). Cashbox. 21 October 1978. Retrieved 21 July 2017.

- ^ "Billboard's Top Album Picks" (PDF). Billboard. 28 July 1973. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Latin Scene". Billboard. Vol. 86, no. 40. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 5 October 1974. p. 41. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

Antonio Aguilar and his wife, Flor Sylvestre [sic], have completed separate LPs, on Musart, dedicated to the music of Puerto Rico.

- ^ "Peregrina (1974) Full Cast & Crew". IMDb. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Latin - Singles To Watch" (PDF). Cashbox. 18 November 1978. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "Latin Picks" (PDF). Cashbox. 23 June 1979. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Montoya Arias, Luis Omar. "El diseño gráfico en la música norteña mexicana" (PDF). AV Investigación. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "FLOR SILVESTRE: SOLEDAD". Google Play. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- ^ Jiménez, Lorena (7 March 2015). "Flor Silvestre, una vida musical". Mural. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre, pilar de la dinastía Aguilar, estrena documental". Esto. 7 March 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- ^ "Vuelve Antonio Aguilar, hijo". El Sol de Mexico. 2 March 2016. Archived from the original on 10 July 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2016.

- ^ "Issues 142-158". Por esto!. Nuestra América, S.A. 1985. p. 38. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Muestra Dalia Inés 'orgullo' familiar". lasnoticiasmexico.com. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Paco Malgesto falleció ayer". El Siglo de Torreón. 23 June 1978. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ Visión: Revista internacional, Volume 12. 1956. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ "Un Aplazamiento Del Divorcio De Malgesto y Flor Silvestre". El Heraldo de Brownsville. UPI. 3 July 1958. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ^ "Le extirparon la mitad del pulmón derecho a la mamá de Pepe Aguilar". TVyNovelas. Archived from the original on 8 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ "Flor Silvestre fue operada de tumor en el pulmón". Univision. Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ EFE (25 November 2020). "Fallece Flor Silvestre, emblemática voz femenina de la canción mexicana". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved November 25, 2020.

- ^ "Muere Flor Silvestre, compañera inseparable de Antonio Aguilar el soyate villanueva zacatecas pepe aguilar majo aguilar angela aguilar leonardo aguilar paco malgesto marcela rubiales - El Sol de Zacatecas | Noticias Locales, Policiacas, sobre México, Zacatecas y el Mundo".

- ^ "Flor Silvestre regresa a los escenarios". El Informador. 24 September 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ "Discos Musart Awards The Golden Clover To Its Best Selling Artists - 1969". Billboard. 28 February 1970. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "Record World Mexican Annual Awards 1972" (PDF). Record World: 38. 29 July 1972. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

- ^ Guzmán Frías, Habacuc (14 November 2001). "Reconocen trayectoria de la dinastía Aguilar". El Universal. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ "Celebran el Los Ángeles desfile por la Independencia de México". Horacero. 7 September 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ Camacho, Alma Rosa (28 September 2009). "Flor Silvestre y Lucha Villa serán homenajeadas". Esto. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Camacho, Alma Rosa (16 November 2012). "Antonio Aguilar y Flor Silvestre, homenajeados". Esto. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ a b Camacho, Alma Rosa (1 August 2013). "Reconocen a histriones del cine mexicano". El Sol de Puebla. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Ortiz, Isela (16 June 2014). "Emotivo homenaje a Flor Silvestre". El Sol de Zacatecas. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ Casillas Gómez, Carlos (10 March 2015). "Homenajean a Flor Silvestre". La Cronica de Hoy - Jalisco. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "Rinden homenaje a Flor Silvestre en Los Ángeles". El Universal. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

- ^ "Homenaje de Aguascalientes a la Señora Flor Silvestre". Palestra Aguascalientes. 7 May 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2015.

External links

- Official website

- Flor Silvestre at IMDb

- Flor Silvestre at the TCM Movie Database

- Flor Silvestre discography at Discogs

- Entries at 45cat.com

- 1930 births

- 2020 deaths

- 20th-century Mexican actresses

- 21st-century Mexican actresses

- 20th-century Mexican women singers

- Actresses from Guanajuato

- Bolero singers

- Columbia Records artists

- Golden Age of Mexican cinema

- Mexican film actresses

- Mexican stage actresses

- Mexican television actresses

- Mexican female equestrians

- Musart Records artists

- People from Salamanca, Guanajuato

- Ranchera singers

- RCA Victor artists

- Singers from Guanajuato

- Western (genre) film actresses

- 21st-century Mexican women singers

- Women in Latin music