White Heat

| White Heat | |

|---|---|

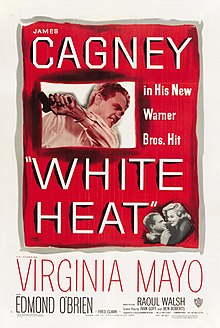

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Raoul Walsh |

| Screenplay by | Ivan Goff Ben Roberts |

| Based on | White Heat by Virginia Kellogg |

| Produced by | Louis F. Edelman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Sidney Hickox |

| Edited by | Owen Marks |

| Music by | Max Steiner |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 114 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1 million[1] or $1,300,000[2] |

| Box office | $1.9 million[3] or $3,483,000[2] |

White Heat is a 1949 American film noir directed by Raoul Walsh and starring James Cagney, Virginia Mayo and Edmond O'Brien.

Written by Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts, White Heat is based on a story by Virginia Kellogg, and is considered to be one of the best gangster movies of all time.[4][5][6][7] In 2003, it was added to the National Film Registry as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress.[8][9]

Plot

Arthur "Cody" Jarrett is a ruthless, psychotic criminal and leader of the Jarrett gang. Although married to Verna, he is overly attached to his equally crooked and determined mother, "Ma" Jarrett.

Cody and his gang rob a mail train in the Sierra Nevada mountains, killing four members of the train's crew. While on the lam, Cody has a severe migraine, which Ma nurses him through. Afterward, Ma and Cody have a quick drink and toast, "Top of the world!", before rejoining the others. The gang splits up.

Informants enable the authorities to close in on a motor court in Los Angeles where Cody, Verna, and Ma are holed up. Cody shoots and wounds US Treasury investigator Philip Evans and makes his escape. He then puts his emergency scheme in motion: confess to a lesser crime committed by an associate in Springfield, Illinois, at the same time as the train job—a federal crime—thus providing him with a false alibi and assuring him a lesser sentence. He turns himself in and is sentenced to one to three years in state prison. Evans, however, plants undercover agent Hank Fallon (as "Vic Pardo") in Cody's cell. His task is to find the "Trader", a fence who launders stolen money for Cody.

On the outside, "Big Ed" Somers, Cody's ambitious right-hand man, takes charge. Verna betrays Cody and joins Ed. Ed pays inmate Roy Parker to kill Cody. In the prison workshop, Parker attempts to drop a heavy piece of machinery on Cody, but Hank pushes Cody out of the way, saving his life and gaining Cody's trust. Ma visits and vows to "take care of" Big Ed, despite Cody's frantic attempts to dissuade her. He starts worrying and decides to break out with Hank. Meanwhile, it is revealed that Verna has murdered Ma, whom she despised (as well as vice versa), by shooting her in the back. Big Ed knows this and holds this information over Verna to keep her with him. When Cody learns of Ma's death from a new inmate, he goes berserk in the mess hall. He concocts an escape plan.

In the infirmary, he is diagnosed as having a "homicidal psychosis" and is recommended for transfer to an asylum. Another inmate sneaks him a gun, which Cody uses to take hostages, and along with Hank and their cellmates, Cody escapes. They also take along Parker. Cody later kills him in cold blood.

When they learn of Cody's escape, Big Ed and Verna anxiously await his return. Verna tries slipping away, but Cody catches her. Although Verna murdered Ma, she convinces Cody that Big Ed did it, so Cody guns him down. The gang welcome the escapees, including Hank, whom Cody likes and trusts. They start planning their next job.

A stranger shows up at the gang's isolated hideout, asking to use the phone. Hank is concerned. Cody introduces the stranger as "The Trader," Daniel Winston. Cody plans to steal a chemical plant's payroll by using an empty tanker truck as a Trojan horse. Hank says he will repair Verna's radio, then rigs a signal transmitter and attaches it to the Trojan tanker; on the way to the plant, he manages to get a message to Evans. The police track the tanker and prepare an ambush.

The gang gets into the payroll office, but the tanker driver, ex-con "Bo" Creel, recognizes Hank and informs Cody. Having tracked the truck to Long Beach, California, using direction finders, the police surround the building and call on Cody to surrender; he decides to fight it out. When the police fire tear gas into the office, Hank manages to escape. In the ensuing gun battle, the police kill most of Cody's gang and Verna is arrested. Cody shoots one of his own men for trying to surrender. Finally, only Cody is still loose. He flees to the top of a gigantic, globe-shaped gas storage tank. After Hank shoots Cody several times with a rifle, Cody fires at the tank, which bursts into flames. He shouts "Made it, Ma! Top of the world!" before the tank explodes.

Cast

- James Cagney as Arthur "Cody" Jarrett[10][11]

- Virginia Mayo as Verna Jarrett[10][11]

- Edmond O'Brien as Hank Fallon, alias Vic Pardo[10][12]

- Margaret Wycherly as "Ma" Jarrett[10][11]

- Steve Cochran as "Big Ed" Somers[10][12]

- John Archer as Philip Evans

- Wally Cassell as Giovanni "Cotton" Valletti

- Fred Clark as Daniel "The Trader" Winston

Uncredited:

- G. Pat Collins as Reader Curtin

- Paul Guilfoyle as Roy Parker

- Ian MacDonald as Bo Creel

- Robert Osterloh as Tommy Ryley

- Ford Rainey as Zuckie Hommel

- Aline Towne as Margaret Baxter

- Jim Thorpe as Inmate (in prison mess hall scene - second convict from the end in pass the message chain)

Production

Development

I used to like to walk out on him, frankly, whenever my contract didn't suit me. I'd cuss him out in Yiddish, which I had learned from Jewish friends in my days at Stuyvesant High School. Drove him wild. 'What'd he say?!' he'd yell. 'What'd he just call me?!'

After winning an Oscar for Yankee Doodle Dandy, Cagney left Warner Brothers in 1942 to form his own production company with his business manager and brother, William. After making four unsuccessful movies (including the well-regarded, but "financially disastrous" adaptation of William Saroyan's The Time of Your Life),[12] Cagney returned to Warner in mid-1949.[11] His decision to return was purely financial; Cagney admitted he "needed the money,"[12] and that he never forgot the "hell" Warner put him through in the 1930s when it came to renewing his contract. Likewise, the last thing Jack Warner wanted to see was Cagney back on his lot; referring to him as "that little bastard",[11] he vowed to never take him back.[14] Cagney's new contract with Warner enabled him to make $250,000 per film on a schedule of one film per year, plus script approval and the opportunity to develop projects for his own company.[12]

To make good on his comeback, Cagney settled on the script for White Heat;[12] on May 6, 1949, he signed on to portray Arthur "Cody" Jarrett.[1] Much to Jack Warner's dismay, it was writers Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts who suggested him for the lead, claiming "there's only one man who can play [Jarrett] and make the rafters rock."[14] For years, Cagney resisted gangster roles in an effort to avoid typecasting, but decided to return to the genre after feeling his box office power waning.[12] Following Cagney's attachment, Warner increased the production budget to $1 million[1] and hired Raoul Walsh to direct. Walsh had previously worked with Cagney on The Roaring Twenties (in 1939) and The Strawberry Blonde (in 1941). However, Cagney was unhappy with the studio's decision to hire Walsh; in part, because he requested Frank McHugh be in the film, but Warner turned his friend down in an attempt to cut costs.[12]

Writing

Warner bought the rights to the story from Virginia Kellogg for $2,000.[1] Being "methodical craftsmen", it took Goff and Roberts six months to complete the first draft. They "would plot in complete detail before even beginning to write, then write their dialogue together, line by line."[14] When Walsh saw it, he pleaded with Cagney's brother, William, to talk Cagney out of doing the picture. According to him, the draft was "bad—a real potboiler," but William reassured Walsh that "Jimmy [would] rewrite it as much as possible."[15]

White Heat was meant to be based on the true story of Ma Barker, a bank robber who raised her four sons as criminals. However, this was changed along with Cagney's involvement; Ma Barker became Ma Jarrett, and her four children were reduced to two. Arthur Barker became Arthur "Cody" Jarrett, a psychopath with a mother fixation.[16][12] Cody's mental illness and the exact cause of his migraines remain a mystery throughout the film. This was done intentionally, enabling viewers to use their imaginations and draw their own conclusions.[12] In total, the script received several rewrites, with input being given from some of Cagney's closest friends. Humphrey Bogart and Frank McHugh worked "after hours" on revisions; with McHugh writing the film's opening scene.[15]

The script is notable for reworking many themes from Cagney's previous films with Warner. Most notably, in The Public Enemy, Cagney smashed a grapefruit into Mae Clarke's face; in White Heat he kicks Virginia Mayo off a chair. In Each Dawn I Die, his character suffers the ill effects of prison; while here, his character has a breakdown in the prison mess hall. Furthermore, in The Roaring Twenties Cagney fought with rival gangsters in a similar fashion to how Cody Jarrett stalks the double-crossing "Big Ed" Somers (portrayed by Steve Cochran).[12]

Filming

The production began on May 5, 1949, and lasted six weeks until completion on June 20. Walsh made use of a number of locations in southern California; first by going to the Santa Susana Mountains (near his home) to shoot "chase scenes".[11] He then moved on to an old Southern Pacific tunnel near Chatsworth to stage the opening robbery scenes.[17] Urban street scenes along with the "Milbank Hotel" were shot in and around Van Nuys.[17] The "hideaway lodge sequences" were shot at the Warner ranch, the interior scenes in the studio itself, and the climax scene at an oil refinery near Torrance, south of Los Angeles.[11][17] The drive-in theater scenes were shot at the now demolished San Val Drive-In in Burbank.[18]

Jack Warner wanted the prison mess hall scene replaced for budgetary reasons, stating the "cost of a single scene with 600 extras and only one line of dialogue would be exorbitant." For this reason, Warner wanted the scene shot in a chapel, but relented when "the writers pointed out that, apart from the fact that Jarrett would [never be willingly caught in a] chapel", the whole point of the scene was to "have a lot of noise, with rattling knives and forks and chatter, that suddenly goes completely silent when Jarrett first screams." The scream was improvised by Cagney, and the shock on everyone's face was real, for neither Cagney nor Walsh informed any of the extras of what was going to happen.[17] Warner agreed to the scene on the condition that it be shot in three hours, so "that the extras were through by lunchtime."[14]

A number of scenes were improvised; Walsh's "personal touches go beyond the script." When Cody and his gang hide out in their cabin just after the train heist, Cody has one of his "debilitating headaches", causing him to fall from his chair and fire off a round from his .45. This was Walsh's idea, as was the showing of Virginia Mayo's upper thigh on screen. Another scene involved Cody giving his wife, Verna, a "seething look", but Walsh improvised and had Cagney knock her off of her chair.[14] Cagney claimed it was his idea "to have Cody climb onto Ma Jarrett's lap and sit there; being soothed during one of his psychotic [episodes]", but Walsh has always denied this; claiming many years later that it was his idea.[19]

Reception

Box office

According to Warner Bros records the film earned $2,189,000 domestically and $1,294,000 foreign.[2]

Critical response

Critical reaction to the film was positive, and today it is considered a classic. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times called it "the acme of the gangster-prison film" and praised its "thermal intensity".[10]

This classic film anticipated the heist films of the early '50s (for example John Huston's 1950 The Asphalt Jungle and Stanley Kubrick's 1956 The Killing), accentuated the semi-documentary style of films of the period (the 1948 The Naked City), and contained film-noirish elements, including the shady black-and-white cinematography, the femme fatale character, and the twisted psyche of the criminal gangster.

— Tim Dirks[citation needed]

In 2005, White Heat was listed in Time magazine's top 100 films of all time.[20] On review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes the film has an approval rating of 97% based on 35 reviews, with a weighted average of 8.40/10. The site's consensus reads: "Raoul Walsh's crime drama goes further into the psychology of a gangster than most fear to tread and James Cagney's portrayal of the tragic anti-hero is constantly volatile".[21]

Awards and nominations

In 1950, Virginia Kellogg was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Story.[22] Also that year writers Ivan Goff and Ben Roberts were nominated for the Edgar Award for Best Motion Picture, by the Mystery Writers of America.[23] In 2003, the United States Library of Congress selected White Heat for preservation in the National Film Registry.[24]

On June 4, 2003, the American Film Institute named Cody Jarrett in its list of the best heroes and villains of the past 100 years, he was voted 26th.[25] Furthermore, in June 2005, "Made it, Ma! Top of the World!" was voted 18th in AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes;[26] while, in June 2008, White Heat was voted 4th in AFI's 10 Top 10 list of gangster movies.[27]

Legacy

Scenes of the film are featured in the 1992 crime-drama film Juice as well as the 1982 Hart to Hart episode "Hart and Sole." In the noir parody Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid, Steve Martin acts in scenes with Cagney's character through special effects and cross-cutting.

The "Made it ma! Top of the world" line is used in the 1991 film Ricochet, in which Denzel Washington recites the quote in the final scene atop a tower. A variation of the quote—"Top of the world, ma!"—appears in the 1986 movie Tough Guys during a scene in which Eli Wallach shoots at cops from a train; the same variation is used in the 1990 film The Adventures of Ford Fairlane by Andrew Dice Clay when he escapes kidnappers and discovers that he is atop the Capitol Records Building. It has also been quoted in a fifth-season episode of Cheers, a second-season episode of Breaking Bad and the series finale of Mixels. The line is also quoted in the Kings of the Sun song "Drop the Gun".

The film has inspired songs such as Madonna's "White Heat" on True Blue; the song was also dedicated to Cagney.[28] Sam Baker's "White Heat" references the plot and dialogue on his 2013 album Say Grace.[29]

The "Made it ma! Top of the world" line also was used in the opening of 50 Cent and PnB Rock's "Crazy" song.

References

- ^ a b c d Nollen, chapter 15, page 1.

- ^ a b c Warner Bros financial information in The William Shaefer Ledger. See Appendix 1, Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, (1995) 15:sup1, 1-31 p 30 DOI: 10.1080/01439689508604551

- ^ "Top-Grossers of 1949", Variety, published January 4, 1950. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ Banks, Alec (October 5, 2017). "The 21 Best Gangster Movies of All Time". High Snobiety. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ^ DeMerritt, Paul (October 16, 2017). "25 Greatest Gangster Movies of All Time". Showbiz Cheat Sheet. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "10 Classic Gangster Movies Better Than 'Gangster Squad'". Indie Wire. January 9, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ Jang, Meena (March 30, 2015). "25 of Hollywood's Classic Gangster Films". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress, National Film Preservation Board. Retrieved June 21, 2019.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ a b c d e f Crowther, Bosley. "James Cagney Back as Gangster in 'White Heat,' Thriller Now at the Strand", The New York Times, published September 3, 1949. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Moss, Ann Marilyn. Film Essay for White Heat, National Film Preservation Board, publishing date unknown. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Eagan, pages 424-425.

- ^ White, Timothy. "James Cagney: Looking Backward", Rolling Stone Magazine, published February 18, 1982. Retrieved July 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Vallance, Tom. "Obituary: Ivan Goff", The Independent, published September 27, 1999. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Moss, page 169.

- ^ Hughes, chapter 4, page 4.

- ^ a b c d Hughes, chapter 4, pages 5-6.

- ^ "San Val Drive-In". www.cinematreasures.org. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Moss, pages 192-195.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (February 12, 2005). "All-Time 100 Movies". Time Magazine. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "White Heat (1949)", Rotten Tomatoes, established August 12, 1998. Date of publication unknown. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ 22nd Academy Award Winners and Nominees, Academy Awards, first published March 23, 1950. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ 1950 Edgar Award Winners and Nominees for Best Motion Picture, Edgar Awards, published 1950. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ Cannady, Sheryl. "Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry", Library of Congress, published December 16, 2003. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ "AFI's 100 YEARS...100 HEROES & VILLAINS", American Film Institute, published June 4, 2003. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ "AFI'S 100 YEARS...100 MOVIE QUOTES", American Film Institute, published June 21, 2005. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ TOP 10 GANGSTER", American Film Institute, published June 17, 2008. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- ^ True Blue (Madonna album)#Background and development

- ^ "Say Grace Lyrics (White Heat)". Sam Baker. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

Further reading

- Eagan, Daniel (2009). America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry. United States: Bloomsbury. ISBN 1441116478.

- Hughes, Howard (2015). Crime Wave: The Filmgoers' Guide to Great Crime Movies. United States: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 0857730487.

- Moss, Ann Marilyn (2011). Raoul Walsh: The True Adventures of Hollywood's Legendary Director. United States: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0813133947.

- Nollen, Scott Allen (2007). Warners Wiseguys : All 112 Films That Robinson, Cagney and Bogart Made for the Studio. United States: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0786432624.

External links

- "White Heat" essay by Marilyn Ann Moss at the National Film Registry

- White Heat at the AFI Catalog of Feature Films

- White Heat at IMDb

- White Heat at AllMovie

- White Heat at the TCM Movie Database

- White Heat at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1949 films

- 1940s crime thriller films

- American black-and-white films

- American crime thriller films

- American heist films

- American prison films

- 1940s English-language films

- Films about organized crime in the United States

- Films directed by Raoul Walsh

- Film noir

- Films scored by Max Steiner

- Films set in California

- Films set in Long Beach, California

- Films set in Illinois

- United States National Film Registry films

- Warner Bros. films

- 1940s American films