Ellis Island

| Ellis Island | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Ellis Island | |

| Location | Upper New York Bay Jersey City, New Jersey and New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°41′58″N 74°02′23″W / 40.69944°N 74.03972°W |

| Area | 27.5 acres (11.1 ha) |

| Elevation | 7 ft (2.1 m)[1] |

| Built | 1900 (Main Building) 1911 (Hospital) |

| Architect | William Alciphron Boring Edward Lippincott Tilton James Knox Taylor |

| Architectural style(s) | Renaissance Revival |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | www |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument |

| Designated | May 11, 1965[2] |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island |

| Designated | October 15, 1966[3] |

| Reference no. | 66000058 |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island |

| Designated | May 27, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1535[4] |

| Type | District/Individual Interior |

| Designated | November 16, 1993[5] |

| Reference no. | 1902 (district), 1903 (main building interior) |

Ellis Island is a federally owned island in New York Harbor, situated within the U.S. states of New Jersey and New York, that was the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United States. From 1892 to 1954, nearly 12 million immigrants arriving at the Port of New York and New Jersey were processed there under federal law.[6] Today, it is part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument and is accessible to the public only by ferry. The north side of the island is the site of the main building, now a national museum of immigration. The south side of the island, including the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, is open to the public only through guided tours.

In the 19th century, Ellis Island was the site of Fort Gibson and later became a naval magazine. The first inspection station opened in 1892 and was destroyed by fire in 1897. The second station opened in 1900 and housed facilities for medical quarantines and processing immigrants. After 1924, Ellis Island was used primarily as a detention center for migrants. During both World War I and World War II, its facilities were also used by the US military to detain prisoners of war. After the immigration station's closure, the buildings languished for several years until they were partially reopened in 1976. The main building and adjacent structures were completely renovated in 1990.

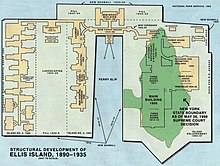

The 27.5-acre (11.1 ha) island was greatly expanded by land reclamation between the late 1890s and the 1930s. Jurisdictional disputes between New Jersey and New York State persisted until the 1998 US Supreme Court ruling in New Jersey v. New York.

Geography and access

Ellis Island is in Upper New York Bay, east of Liberty State Park and north of Liberty Island. While most of the island is in Jersey City, New Jersey, a small section is an exclave of New York City.[7][8] The island has a land area of 27.5 acres (11.1 ha), much of which is from land reclamation.[9] The natural island and contiguous areas comprise 4.68 acres (1.89 ha) within New York, and are located on the northern portion of the present-day island.[8] The artificial land is part of New Jersey.[10][8] The island has been owned and administered by the federal government of the United States since 1808 and operated by the National Park Service since 1965.[11][12]

Land expansion

Initially, much of the Upper New York Bay's western shore consisted of large tidal flats with vast oyster beds, which were a major source of food for the Lenape. Ellis Island was one of three "Oyster Islands," the other two being Liberty Island and the now-subsumed Black Tom Island.[13][14][15] In the late 19th century, the federal government began expanding the island by land reclamation to accommodate its immigration station, and the expansions continued until 1934.[16]

The fill was acquired from the ballast of ships, as well as material excavated from the first line of the New York City Subway.[17] It also came from the railyards of the Lehigh Valley Railroad and the Central Railroad of New Jersey. It eventually obliterated the oyster beds, engulfed one of the Oyster Islands, and brought the shoreline much closer to the others.[18]

The current island is shaped like a "C", with two landmasses of equal size on the northeastern and southwestern sides, separated by what was formerly a ferry pier.[19][20] It was originally three separate islands. The current north side, formerly called island 1, contains the original island and the fill around it. The current south side was composed of island 2, created in 1899, and island 3, created in 1906. Two eastward-facing ferry docks separated the three numbered landmasses.[19][20]

The fill was retained with a system of wood piles and cribbing, and later encased with more than 7,700 linear feet of concrete and granite sea wall. It was placed atop either wood piles, cribbing, or submerged bags of concrete. In the 1920s, the second ferry basin between islands 2 and 3 was infilled to create the great lawn, forming the current south side of Ellis Island. As part of the project, a concrete and granite seawall was built to connect the tip of these landmasses.[21]

State sovereignty dispute

The circumstances which led to an exclave of New York being located within New Jersey began in the colonial era, after the British takeover of New Netherland in 1664. A clause in the colonial land grant outlined the territory that the proprietors of New Jersey would receive as being "westward of Long Island, and Manhitas Island and bounded on the east part by the main sea, and part by Hudson's river."[22][23]

As early as 1804, attempts were made to resolve the status of the state line.[24] The City of New York claimed the right to regulate trade on all waters. This was contested in Gibbons v. Ogden, which decided that the regulation of interstate commerce fell under the authority of the federal government, thus influencing competition in the newly developing steam ferry service in New York Harbor.[25] In 1830, New Jersey planned to bring suit to clarify the border, but the case was never heard.[26] The matter was resolved with a compact between the states, ratified by U.S. Congress in 1834.[26][27][28] This set the boundary line at the middle of the Hudson River and New York Harbor; however, New York was guaranteed "exclusive jurisdiction of and over all the waters of Hudson River lying west of Manhattan and to the south of the mouth of Spuytenduyvil Creek; and of and over the lands covered by the said waters, to the low-water mark on the New Jersey shore."[29] This was later confirmed in other cases by the U.S. Supreme Court.[18][24][30][31]

New Jersey contended that the artificial portions of the island were part of New Jersey, since they were outside New York's border. In 1956, after the closure of the U.S. immigration station two years prior, the Mayor of Jersey City Bernard J. Berry commandeered a U.S. Coast Guard cutter and led a contingent of New Jersey officials on an expedition to claim the island.[32]

Jurisdictional disputes reemerged in the 1980s with the renovation of Ellis Island,[33] and then again in the 1990s with the proposed redevelopment of the south side.[34] New Jersey sued in 1997.[34] The lawsuit was escalated to the Supreme Court, which ruled in New Jersey v. New York. 523 U.S. 767 (1998)[26][35][36] The border was redrawn using geographic information science data:[37] It was decided that 22.80 acres (9.23 ha) of the land fill area are territory of New Jersey and that 4.68 acres (1.89 ha), including the original island, are territory of New York.[8] This caused some initial confusion, as some buildings straddled the interstate border.[26] The ruling had no effect on the status of Liberty Island.[38]

Although the island remained under federal ownership after the lawsuit, New Jersey and New York agreed to share jurisdiction over the land itself. Neither state took any fiscal or physical responsibility for the maintenance, preservation, or improvement of any of the historic properties, and each state has jurisdiction over its respective land areas. Jersey City and New York City then gave separate tax lot numbers to their respective claims.[35][a]

Public access

Two ferry slips are located on the northern side of the basin that bisects Ellis Island. No charge is made for entrance to the Statue of Liberty National Monument, but there is a cost for the ferry service.[44] A concession was granted in 2007 to Statue Cruises to operate the transportation and ticketing facilities, replacing Circle Line, which had operated the service since 1953.[45] The ferries travel from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Battery in Lower Manhattan.[46] The NPS also offers guided public tours of the south side as part of the "Hard Hat Tour".[47][48]

A bridge to Liberty State Park was built in 1986 for transporting materials and personnel during the island's late-1980s restoration. Originally slated to be torn down in 1992,[49] it remained after construction was complete.[50] It is not open to the public. The city of New York and the island's private ferry operator have opposed proposals to use it or replace it with a pedestrian bridge,[51] and a 1995 proposal for a new pedestrian bridge to New Jersey was voted down in the United States House of Representatives.[50] The bridge is not strong enough to be classified as a permanent bridge, and any action to convert it into a pedestrian passageway would require renovations.[52]

History

Precolonial and colonial use

The present-day Ellis Island was created by retreating glaciers at the end of the Wisconsin glaciation about 15,000 years ago. The island was described as a "hummock along a plain fronting the west side of the Hudson River estuary,"[53] and when the glaciers melted, the water of the Upper New York Bay surrounded the mass.[53] The native Mohegan name for the island was "Kioshk", meaning "Gull Island",[54][55][56] in reference to Ellis Island's former large population of seagulls.[54] Kioshk was composed mostly of marshy, brackish lowlands that disappeared underwater at high tide.[53] The Native American tribes who lived nearby are presumed to have been hunter-gatherers who used the island to hunt for fish and oysters, as well as to build transient hunting and fishing communities there.[57][58] It is unlikely that the Native Americans established permanent settlements on Kioshk, since the island would have been submerged at high tide.[58]

In 1630, the Dutch bought Kioshk as a gift for Michael Reyniersz Pauw,[b] who had helped found New Netherland.[58][59][60] When the Dutch settled the area as part of New Netherland, the three islands in Upper New York Bay—Liberty, Black Tom, and Ellis Islands—were given the name Oyster Islands, alluding to the large oyster population nearby. The present-day Ellis Island was thus called "Little Oyster Island",[14][15][61] a name that persisted through at least the early 1700s.[62][c] Little Oyster Island was then sold to Captain William Dyre c. 1674,[d] then to Thomas Lloyd on April 23, 1686.[64][58] The island was then sold several more times,[64] including to Enoch and Mary Story.[58] During colonial times, Little Oyster Island became a popular spot for hosting oyster roasts, picnics, and clambakes because of its rich oyster beds. Evidence of recreational uses on the island was visible by the mid-18th century with the addition of commercial buildings to the northeast shore.[58][65]

By the 1760s, Little Oyster Island became a public execution site for pirates, with executions occurring at one tree in particular, the "Gibbet Tree".[56][66][55] However, there is scant evidence that this was common practice.[58] Little Oyster Island was acquired by Samuel Ellis, a colonial New Yorker and merchant from Wrexham, Wales, in 1774.[67] He unsuccessfully attempted to sell the island nine years later.[68][69] Ellis died in 1794,[67][69][70] and as per his will, the ownership of Ellis Island passed to his daughter Catherine Westervelt's unborn son, who was also named Samuel. When the junior Samuel died shortly after birth, ownership passed to the senior Samuel's other two daughters, Elizabeth Ryerson and Rachel Cooder.[69][70]

Military use and Fort Gibson

Ellis Island was also used by the military for almost 80 years.[71] By the mid-1790s, as a result of the United States' increased military tensions with Britain and France, a U.S. congressional committee drew a map of possible locations for the First System of fortifications to protect major American urban centers such as New York Harbor.[72][73]A small part of Ellis Island from "the soil from high to low waters mark around Ellis's Island" was owned by the city. On April 21, 1794, the city deeded that land to the state for public defense purposes.[69][74] The following year, the state allotted $100,000 for fortifications on Bedloe's, Ellis, and Governors Islands,[69] as well as the construction of Castle Garden (now Castle Clinton[75]) along the Battery on Manhattan island.[69] Batteries and magazines were built on Ellis Island in preparation for a war.[76] A jetty was added to the northwestern extremity of the island, possibly from soil excavated from an inlet at the northeastern corner; the inlet was infilled by 1813.[69] Though the military threat never materialized, further preparations were made in the late 1790s, when the Quasi War sparked fears of war with France;[69][27] these new preparations were supervised by Ebenezer Stevens.[70][77] The military conflict also failed to occur, and by 1805, the fort had become rundown.[28]

Stevens, who observed that the Ellis family still owned most of the island, suggested selling off the land to the federal government.[70] Samuel Ryerson, one of Samuel Ellis's grandsons, deeded the island to John A. Berry in 1806.[70][78][74] The remaining portion of the island was acquired by condemnation the next year, and it was ceded to the United States on June 30, 1808, for $10,000.[71][70][27][32] Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Williams, placed in charge of New York Harbor defenses in the early 1800s, proposed several new fortifications around the harbor as part of the Second System of fortifications. The new fortifications included increased firepower and improved weaponry.[79][27] The War Department established a circular stone 14-gun battery, a mortar battery (possibly of six mortars), magazine, and barracks.[80][81][82] The fort was initially called Crown Fort, but by the end of the War of 1812 the battery was named Fort Gibson, in honor of Colonel James Gibson of the 4th Regiment of Riflemen, who was killed in the war during the Siege of Fort Erie.[83][71] The fort was not used in combat during the war, and instead served as a barracks for the 11th Regiment, as well as a jail for British prisoners of war.[28]

Immediately after the end of the War of 1812, Fort Gibson was largely used as a recruiting depot. The fort went into decline due to under-utilization, and it was being jointly administered by the U.S. Army and Navy by the mid-1830s.[28] Around this time, in 1834, the extant portions of Ellis Island was declared to be an exclave of New York within the waters of New Jersey.[26][27][28] The era of joint administration was short-lived: the Army took over the fort's administration in 1841, demoted the fort to an artillery battery, and stopped garrisoning the fort, leaving a small Navy guard outside the magazine. By 1854, Battery Gibson contained an 11-gun battery, three naval magazines, a short railroad line, and several auxiliary structures such as a cookhouse, gun carriage house, and officers' quarters.[84] The Army continued to maintain the fort until 1860, when it abandoned the weapons at Battery Gibson.[27][85] The artillery magazine was expanded in 1861, during the American Civil War, and part of the parapet was removed.[84]

At the end of the Civil War, the fort declined again, this time to an extent that the weaponry was rendered unusable.[84] Through the 1870s, the Navy built additional buildings for its artillery magazine on Ellis Island,[86] eventually constructing 11 buildings in total.[87] Complaints about the island's magazines started to form, and by the 1870s, The New York Sun was publishing "alarming reports" about the magazines.[70] The guns were ordered removed in 1881, and the island passed under the complete control of the Navy's Bureau of Ordnance.[85]

First immigration station

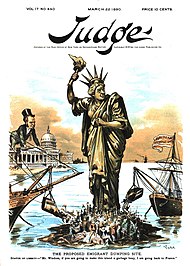

"Mr. Windom, if you are going to make this island a garbage heap, I am returning to France"

The Army had unsuccessfully attempted to use Ellis Island "for the convalescence for immigrants" as early as 1847.[70] Across New York Harbor, Castle Clinton had been used as an immigration station since 1855, processing more than eight million immigrants during that time.[88][89] The individual states had their own varying immigration laws until 1875, but the federal government regarded Castle Clinton as having "varied charges of mismanagement, abuse of immigrants, and evasion of the laws", and as such, wanted it to be completely replaced.[90] The federal government assumed control of immigration in early 1890 and commissioned a study to determine the best place for the new immigration station in New York Harbor.[90] Among members of the United States Congress, there were disputes about whether to build the station on Ellis, Governors, or Liberty Islands. Initially, Liberty Island was selected as the site for the immigration station,[90] but due to opposition for immigration stations on both Liberty and Governors Islands, the committee eventually decided to build the station on Ellis Island.[e][92] Since Castle Clinton's lease was about to expire, Congress approved a bill to build an immigration station on Ellis Island.[93]

On April 11, 1890, the federal government ordered the magazine at Ellis Island be torn down to make way for the U.S.'s first federal immigration station at the site.[59] The Department of the Treasury, which was in charge of constructing federal buildings in the U.S.,[94] officially took control of the island that May 24.[91] Congress initially allotted $75,000 (equivalent to $2,543,000 in 2023) to construct the station and later doubled that appropriation.[17][91] While the building was under construction, the Barge Office at the Battery was used for immigrant processing.[95] During construction, most of the old Battery Gibson buildings were demolished, and Ellis Island's land size was almost doubled to 6 acres (2.4 ha).[96][94] The main structure was a two-story structure of Georgia Pine,[95][19] which was described in Harper's Weekly as "a latterday watering place hotel" measuring 400 by 150 ft (122 by 46 m).[96] Its outbuildings included a hospital, detention building, laundry building, and utility plant that were all made of wood. Some of the former stone magazine structures were reused for utilities and offices. Additionally, a ferry slip with breakwater was built to the south of Ellis Island.[95][96][19] Following further expansion, the island measured 11 acres (4.5 ha) by the end of 1892.[91]

The station opened on January 1, 1892,[66][19][97][98] and its first immigrant was Annie Moore, a 17-year-old girl from Cork, Ireland, who was traveling with her two brothers to meet their parents in the U.S.[56][97][99][100] On the first day, almost 700 immigrants passed over the docks.[91] Over the next year, over 400,000 immigrants were processed at the station.[f][102][101] The processing procedure included a series of medical and mental inspection lines, and through this process, some 1% of potential immigrants were deported.[103] Additional building improvements took place throughout the mid-1890s,[104][105][106] and Ellis Island was expanded to 14 acres (5.7 ha) by 1896. The last improvements, which entailed the installation of underwater telephone and telegraph cables to Governors Island, were completed in early June 1897.[104] On June 15, 1897, the wooden structures on Ellis Island were razed in a fire of unknown origin. While there were no casualties, the wooden buildings had completely burned down after two hours, and all immigration records from 1855 had been destroyed.[70][102][104][107] Over five years of operation, the station had processed 1.5 million immigrants.[102][94]

Second immigration station

Design and construction

Following the fire, passenger arrivals were again processed at the Barge Office, which was soon unable to handle the large volume of immigrants.[88][108][109] Within three days of the fire, the federal government made plans to build a new, fireproof immigration station.[88][108] Legislation to rebuild the station was approved on June 30, 1897,[110] and appropriations were made in mid-July.[111] By September, the Treasury's Supervising Architect, James Knox Taylor, opened an architecture competition to rebuild the immigration station.[111] The competition was the second to be conducted under the Tarsney Act of 1893, which had permitted private architects to design federal buildings, rather than government architects in the Supervising Architect's office.[102][112][113] The contest rules specified that a "main building with annexes" and a "hospital building", both made of fireproof materials, should be part of each nomination.[112] Furthermore, the buildings had to be able to host a daily average of 1,000 and maximum of 4,000 immigrants.[114]

Several prominent architectural firms filed proposals,[111][114][115] and by December, it was announced that Edward Lippincott Tilton and William A. Boring had won the competition.[102][116] Tilton and Boring's plan called for four new structures: a main building in the French Renaissance style, as well as the kitchen/laundry building, powerhouse, and the main hospital building.[111][115][117][118] The plan also included the creation of a new island called island 2, upon which the hospital would be built, south of the existing island (now Ellis Island's north side).[111][115] A construction contract was awarded to the R. H. Hood Company in August 1898, with the expectation that construction would be completed within a year,[119][120][121] but the project encountered delays because of various obstacles and disagreements between the federal government and the Hood Company.[119][122] A separate contract to build the 3.33-acre (1.35 ha) island 2 had to be approved by the War Department because it was in New Jersey's waters; that contract was completed in December 1898.[123] The construction costs ultimately totaled $1.5 million.[19]

Early expansions

The new immigration station opened on December 17, 1900, without ceremony. On that day, 2,251 immigrants were processed.[102][124][125] Almost immediately, additional projects commenced to improve the main structure, including an entrance canopy, baggage conveyor, and railroad ticket office. The kitchen/laundry and powerhouse started construction in May 1900 and were completed by the end of 1901.[125][126] A ferry house was also built between islands 1 and 2 c. 1901.[127] The hospital, originally slated to be opened in 1899, was not completed until November 1901, mainly due to various funding delays and construction disputes.[128] The facilities proved barely able to handle the flood of immigrants that arrived, and as early as 1903, immigrants had to remain in their transatlantic boats for several days due to inspection backlogs.[129][130] Several wooden buildings were erected by 1903, including waiting rooms and a 700-bed barracks,[130] and by 1904, over a million dollars' worth of improvements were proposed.[131] The hospital was expanded from 125 to 250 beds in February 1907, and a new psychopathic ward debuted in November of the same year. Also constructed was an administration building adjacent to the hospital.[127][132]

Immigration commissioner William Williams made substantial changes to Ellis Island's operations, and during his tenure from 1902 to 1905 and 1909–1913, Ellis Island processed its peak number of immigrants.[129] Williams also made changes to the island's appearance, adding plants and grading paths upon the once-barren landscape of Ellis Island.[133][134] Under Williams's supervision, a 4.75-acre (1.92 ha) third island was built to accommodate a proposed contagious-diseases ward, separated from existing facilities by 200 ft (61 m) of water.[135][19][132] Island 3, as it was called, was located to the south of island 2 and separated from that island by a now-infilled ferry basin.[19] The government bought the underwater area for island 3 from New Jersey in 1904,[135][136] and a contract was awarded in April 1905.[135] The islands were all connected via a cribwalk on their western sides (later covered with wood canopy), giving Ellis Island an overall "E"-shape.[20][137] Upon the completion of island 3 in 1906, Ellis Island covered 20.25 acres (8.19 ha).[138] A baggage and dormitory building was completed c. 1908–1909,[129][132][139] and the main hospital was expanded in 1909.[140] Alterations were made to the registry building and dormitories as well, but even this was insufficient to accommodate the high volume of immigrants.[141] In 1911, Williams alleged that Congress had allocated too little for improvements to Ellis Island,[142] even though the improvement budget that year was $868,000.[143]

Additional improvements and routine maintenance work were completed in the early 1910s.[139][141] A greenhouse was built in 1910,[139][144] and the contagious-diseases ward on island 3 opened the following June.[145][141] In addition, the incinerator was replaced in 1911,[140][132] and a recreation center operated by the American Red Cross was also built on island 2 by 1915.[140][144] These facilities generally followed the design set by Tilton and Boring.[132] When the Black Tom explosion occurred on Black Tom Island in 1916, the complex suffered moderate damage; though all immigrants were evacuated safely, the main building's roof collapsed, and windows were broken. The main building's roof was replaced with a Guastavino-tiled arched ceiling by 1918.[146][147][148] The immigration station was temporarily closed during World War I in 1917–1919, during which the facilities were used as a jail for suspected enemy combatants, and later as a treatment center for wounded American soldiers. Immigration inspections were conducted aboard ships or at docks.[19][140][149][148] During the war, immigration processing at Ellis Island declined by 97%, from 878,000 immigrants per year in 1914 to 26,000 per year in 1919.[150]

Ellis Island's immigration station was reopened in 1920, and processing had rebounded to 560,000 immigrants per year by 1921.[19][151] There were still ample complaints about the inadequate condition of Ellis Island's facilities.[152][153] However, despite a request for $5.6 million in appropriations in 1921,[154] aid was slow to materialize, and initial improvement work was restricted to smaller projects such as the infilling of the basin between islands 2 and 3.[155][151] Other improvements included rearranging features such as staircases to improve pedestrian flow.[155] These projects were supported by president Calvin Coolidge, who in 1924 requested that Congress approve $300,000 in appropriations for the island.[155][156] The allocations were not received until the late 1920s.[155]

Conversion to detention center

With the passing of the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, the number of immigrants being allowed into the United States declined greatly, ending the era of mass immigration.[157][19][158] Following the Immigration Act of 1924, strict immigration quotas were enacted, and Ellis Island was downgraded from a primary inspection center to an immigrant-detention center, hosting only those that were to be detained or deported (see § Mass detentions and deportations).[19][158][159] Final inspections were now instead conducted on board ships in New York Harbor. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 further decreased immigration, as people were now discouraged from immigrating to the U.S.[158] Because of the resulting decline in patient counts, the hospital closed in 1930.[160][161][162]

Edward Corsi, who himself was an immigrant, became Ellis Island commissioner in 1931 and commenced an improvement program for the island. The initial improvements were utilitarian, focusing on such aspects as sewage, incineration, and power generation.[163][164] In 1933, a federal committee led by the Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, was established to determine what operations and facilities needed improvement.[165] The committee's report, released in 1934, suggested the construction of a new class-segregated immigration building, recreation center, ferry house, verandas, and doctors/nurses' quarters, as well as the installation of a new seawall around the island.[166][167][168] These works were undertaken using Public Works Administration funding and Works Progress Administration labor, and were completed by the late 1930s. As part of the project, the surgeon's house and recreation center were demolished,[128][144] and Edward Laning commissioned some murals for the island's buildings.[169] Other improvements included the demolition of the greenhouse, the completion of the infilling of the basin between islands 2 and 3, and various landscaping activities such as the installation of walkways and plants.[170][168] However, because of the steep decline in immigration, the immigration building went underused for several years, and it started to deteriorate.[166][164]

With the start of World War II in 1939, Ellis Island was again utilized by the military, this time being used as a United States Coast Guard base.[171][172][173] As during World War I, the facilities were used to detain enemy soldiers in addition to immigrants, and the hospital was used for treating injured American soldiers.[173] So many combatants were detained at Ellis Island that administrative offices were moved to mainland Manhattan in 1943, and Ellis Island was used solely for detainment.[164][174]

By 1947, shortly after the end of World War II, there were proposals to close Ellis Island due to the massive expenses needed for the upkeep of a relatively small detention center.[175] The hospital was closed in 1950–1951 by the United States Public Health Service, and by the early 1950s, there were only 30 to 40 detainees left on the island.[19][176][177] The island's closure was announced in mid-1954, when the federal government announced that it would construct a replacement facility on Manhattan.[178][177] Ellis Island closed on November 12, 1954, with the departure of its last detainee, Norwegian merchant seaman Arne Pettersen, who had been arrested for overstaying his shore leave.[179] At the time, it was estimated that the government would save $900,000 a year from closing the island.[179] The ferryboat Ellis Island, which had operated since 1904, stopped operating two weeks later.[70][180]

Post-closure

Initial redevelopment plans

After the immigration station closed, the buildings fell into disrepair and were abandoned,[181] and the General Services Administration (GSA) took over the island in March 1955.[70] The GSA wanted to sell off the island as "surplus property"[182] and contemplated several options, including selling the island back to the city of New York[183] or auctioning it to a private buyer.[184] In 1959, real estate developer Sol Atlas unsuccessfully bid for the island, with plans to turn it into a $55 million resort with a hotel, marina, music shell, tennis courts, swimming pools, and skating rinks.[185][186] The same year, Frank Lloyd Wright designed the $100 million "Key Project",[h] which included housing, hotels, and large domes along the edges. However, Wright died before presenting the project.[187][188] Other attempts at redeveloping the site, including a college,[189] a retirement home,[181] an alcoholics' rehabilitation center,[190] and a world trade center[191] were all unsuccessful.[181][192] In 1963, the Jersey City Council voted to rezone the island's area within New Jersey for high-rise residential, monument/museum, or recreational use, though the new zoning ordinance banned "Coney Island"-style amusement parks.[193][194]

In June 1964, the National Park Service published a report that proposed making Ellis Island part of a national monument.[195] This idea was approved by Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall in October 1964.[196] Ellis Island was added to the Statue of Liberty National Monument on May 11, 1965,[2][197][198] and that August, President Lyndon B. Johnson approved the redevelopment of the island as a museum and park.[198][199]

The initial master plan for the redevelopment of Ellis Island, designed by Philip Johnson, called for the construction of the Wall, a large "stadium"-shaped monument to replace the structures on the island's northwest side, while preserving the main building and hospital.[200][201] However, no appropriations were immediately made, other than a $250,000 allocation for emergency repairs in 1967. By the late 1960s, the abandoned buildings were deteriorating severely.[202][203][201] Johnson's plan was never implemented due to public opposition and a lack of funds.[201] Another master plan was proposed in 1968, which called for the rehabilitation of the island's northern side and the demolition of all buildings, including the hospital, on the southern side.[204] The Jersey City Jobs Corpsmen started rehabilitating part of Ellis Island the same year, in accordance with this plan.[205][204] This was soon halted indefinitely because of a lack of funding.[204] In 1970, a squatters' club called the National Economic Growth and Reconstruction Organization (NEGRO) started refurbishing buildings as part of a plan to turn the island into an addiction rehabilitation center,[206] but were evicted after less than two weeks.[207][208] NEGRO's permit to renovate the island were ultimately terminated in 1973.[208]

Restoration and reopening of north side

In the 1970s, the NPS started restoring the island by repairing seawalls, eliminating weeds, and building a new ferry dock.[209] Simultaneously, Peter Sammartino launched the Restore Ellis Island Committee to raise awareness and money for repairs.[70][210][211] The north side of the island, comprising the main building and surrounding structures, was rehabilitated and partially reopened for public tours in May 1976.[70][209][212][213] The plant was left unrepaired to show the visitors the extent of the deterioration.[213] The NPS limited visits to 130 visitors per boat, or less than 75,000 visitors a year.[209] Initially, only parts of three buildings were open to visitors. Further repairs were stymied by a lack of funding, and by 1982, the NPS was turning to private sources for funds.[214]

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Centennial Commission, led by Chrysler Corporation chair Lee Iacocca with former President Gerald Ford as honorary chairman, to raise the funds needed to complete the work.[70][215][216] The plan for Ellis Island was to cost $128 million,[217] and by the time work commenced in 1984, about $40 million had been raised.[218] Through its fundraising arm, the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., the group eventually raised more than $350 million in donations for the renovations of both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.[219] Initial restoration plans included renovating the main building, baggage and dormitory building, and the hospital, as well as possibly adding a bandshell, restaurant, and exhibits.[220] Two firms, Notter Finegold & Alexander and Beyer Blinder Belle, designed the renovation.[221] In advance of the renovation, public tours ceased in 1984, and work started the following year.[70][222] As part of the restoration, the powerhouse was renovated, while the incinerator, greenhouse, and water towers were removed.[223][144] The kitchen/laundry and baggage/dormitory buildings were restored to their original condition while the main building was restored to its 1918–1924 appearance.[222][224]

The main building opened as a museum on September 10, 1990.[225][226][227] Further improvements were made after the north side's renovation was completed. The Wall of Honor, a monument to raise money for the restoration, was completed in 1990 and reconstructed starting in 1993.[228][223] A research facility with online database, the American Family Immigration History Center, was opened in April 2001.[70][229] Subsequently, the ferry building was restored for $6.4 million and reopened in 2007.[230] The north side was temporarily closed after being damaged in Hurricane Sandy in October 2012,[231] though the island and part of the museum reopened exactly a year later, after major renovations.[232][233][234] In March 2020, the island was closed temporarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic;[235] it reopened in August 2020, initially with strict capacity limits.[236]

Structures

Buildings and structures at Ellis Island

- Main building

- Kitchen-laundry

- Baggage-dormitory

- Bakery-carpentry shop

- Powerhouse

- Ferry building

- Laundry-hospital outbuilding

- Psychopathic ward

- Main hospital building

- Recreation building and pavilion

- Office building; morgue

- Powerhouse and laundry

- Measles wards (A, C, G, E)

- Administration building and kitchen

- Measles wards (B, D, F, H)

- Isolation wards (I, K, L)

- Staff House

- Wall of Honor

The current complex was designed by Edward Lippincott Tilton and William A. Boring, who performed the commission under the direction of the Supervising Architect for the U.S. Treasury, James Knox Taylor.[119][237] Their plan, submitted in 1898, called for structures to be located on both the northern and southern portions of Ellis Island. The plan stipulated a large main building, a powerhouse, and a new baggage/dormitory and kitchen building on the north side of Ellis Island; a hospital on the south side; and a ferry dock with covered walkways at the head of the ferry basin, on the west side of the island.[118][238] The plan roughly corresponds to what was ultimately built.[20][239]

North side

The northern half of Ellis Island is composed of the former island 1. Only the areas associated with the original island, including much of the main building, are in New York; the remaining area is in New Jersey.[19][20]

Main building

The present three-story main structure was designed in French Renaissance style. It is made of a steel frame, with a facade of red brick in Flemish bond ornamented with limestone trim.[124][240][241] The structure is located 8 ft (2.4 m) above the mean waterline to prevent flooding.[119] The building was initially composed of a three-story center section with two-story east and west wings, though the third stories of each wing were completed in the early 1910s. Atop the corners of the building's central section are four towers capped by cupolas of copper cladding.[242][241] Some 160 rooms were included within the original design to separate the different functions of the building. Namely, the first floor was initially designed to handle baggage, detention, offices, storage and waiting rooms; the second floor, primary inspection; and the third floor, dormitories.[238] However, in practice, these spaces generally served multiple functions throughout the immigration station's operating history. At opening, it was estimated that the main building could inspect 5,000 immigrants per day.[243][244] The main building's design was highly acclaimed; at the 1900 Paris Exposition, it received a gold medal, and other architectural publications such as the Architectural Record lauded the design.[245]

The first floor contained detention rooms, social service offices, and waiting rooms on its west wing, a use that remained relatively unchanged.[246] The central space was initially a baggage room until 1907, but was subsequently subdivided and later re-combined into a single records room.[246] The first floor's east wing also contained a railroad waiting room and medical offices, though much of the wing was later converted to record rooms.[247] A railroad ticket office annex was added to the north side of the first floor in 1905–1906.[241] The south elevation of the first floor contains the current immigration museum's main entrance, approached by a slightly sloped passageway covered by a glass canopy. Though the canopy was added in the 1980s, it evokes the design of an earlier glass canopy on the site that existed from 1902 to 1932.[248][240]

Lost baggage is the cause of their worried expressions. At the height of immigration the entire first floor of the administration building was used to store baggage.[249]

A 200 by 100 ft (61 by 30 m) registry room, with a 56 ft (17 m) ceiling, is located on the central section of the second floor.[243][250] The room was used for primary inspections.[251][247] Initially, there were handrails within the registry room that separated the primary inspection into several queues, but c. 1911 these were replaced with benches. A staircase from the first floor formerly rose into the middle of the registry room, but this was also removed around 1911.[237][141] When the room's roof collapsed during the Black Tom explosion of 1916, the current Guastavino-tiled arched ceiling was installed, and the asphalt floor was replaced with red Ludowici tile.[148][250] There are three large arched openings each on the northern and southern walls, filled-in with grilles of metal-and-glass. The southern elevation retains its original double-height arches, while the lower sections of the arches on the northern elevations were modified to make way for the railroad ticket office.[242][241] On all four sides of the room, above the level of the third floor, is a clerestory of semicircular windows.[250][242][241] The east wing of the second floor was used for administrative offices,[252] while the west wing housed the special inquiry and deportation divisions, as well as dormitories.[247]

On the third floor is a balcony surrounding the entire registry room.[237][238] There were also dormitories for 600 people on the third floor.[243] Between 1914 and 1918, several rooms were added to the third floor. These rooms included offices as well as an assembly room that were later converted to detention.[252]

The remnants of Fort Gibson still exist outside the main building. Two portions are visible to the public, including the remnants of the lower walls around the fort.[248]

Kitchen and laundry

The kitchen and laundry structure is a two-and-a-half-story structure located west of the main building.[20][239] It is made of a steel frame and terracotta blocks, with a granite base and a facade of brick in Flemish bond.[126] Originally designed as two separate structures, it was redesigned in 1899 as a single structure with kitchen-restaurant and laundry-bathhouse components,[253] and was subsequently completed in 1901.[125][126] A one-and-a-half-story ice plant on the northern elevation was built between 1903 and 1908, and was converted into a ticket office in 1935. It has a facade of brick in English and stretcher bond.[126] Today, the kitchen and laundry contains NPS offices[254] as well as the museum's Peopling of America exhibit.[255]

The building has a central portion with a narrow gable roof, as well as pavilions on the western and eastern sides with hip roofs; the roof tiling was formerly of slate and currently of Ludowici terracotta. The larger eastern pavilion, which contained the laundry-bathhouse, had hipped dormers. The exterior-facing window and door openings contain limestone features on the facade, while the top of the building has a modillioned copper cornice. Formerly, there was also a two-story porch on the southern elevation. Multiple enclosed passageways connect the kitchen and laundry to adjacent structures.[126]

Bakery and carpentry shop

The bakery and carpentry shop is a two-story structure located west of the kitchen and laundry building. It is roughly rectangular and oriented north–south.[20][239] It is made of a steel frame with a granite base, a flat roof, and a facade of brick in Flemish bond. The building was constructed in 1914–1915 to replace the separate wooden bakery and carpentry shop buildings, as well as two sheds and a frame waiting room. There are no exterior entrances, and the only access is via the kitchen and laundry.[256][257] The first floor generally contained oven rooms, baking areas and storage while the second floor contained the carpentry shop.[257]

Baggage and dormitory

The baggage and dormitory structure is a three-story structure located north of the main building.[20][239] It is made of a steel frame and terracotta blocks, with a limestone base and a facade of brick in Flemish bond.[258] Completed as a two-story structure c. 1908–1909,[129][132][139] the baggage and dormitory building replaced a 700-bed wooden barracks nearby that operated between 1903 and 1911.[258] The baggage and dormitory initially had baggage collection on its first floor, dormitories and detention rooms on its second floor, and a tiled garden on its roof.[258][259] The building received a third story, and a two-story annex to the north side, in 1913–1914.[258][259] Initially, the third floor included additional dormitory space while the annex provided detainees with outdoor porch space.[259] A detainee dining room on the first floor was expanded in 1951.[257]

The building is mostly rectangular except for its northern annex and contains an interior courtyard, skylighted at the second floor. On its facade the first story has rectangular windows in arched window openings while the second and third stories have rectangular windows and window openings. There are cornices below the second and third stories. The annex contains wide window openings with narrow brick piers outside them. The roof's northwest corner contains a one-story extension. Multiple wings connect the baggage and laundry to its adjacent buildings.[258]

Powerhouse

The powerhouse of Ellis Island is a two-story structure located north of the kitchen and laundry building and west of the baggage and dormitory building. It is roughly rectangular and oriented north–south.[20][239] Like the kitchen and laundry, it was completed in 1901.[125][260][261] It is made of a steel frame with a granite base, a facade of brick in Flemish bond, and decorative bluestone and limestone elements. The hip roof contains dormers and is covered with terracotta tiling. A brick smokestack rises 111 ft (34 m) from ground level.[258]

Formerly, the powerhouse provided almost all power for Ellis Island. A coal trestle at the northwest end was used to transport coal for power generation from 1901 to 1932, when the powerhouse started using fuel oil.[258] The powerhouse also generated steam for the island.[262] After the immigration station closed, the powerhouse deteriorated[213] and was left unrepaired until the 1980s renovation.[223] The powerhouse is no longer operational; instead, the island receives power from 13,200-volt cables that lead from a Public Service Electric & Gas substation in Liberty State Park. The powerhouse contains sewage pumps that can dispose of up to 480 U.S. gal/min (1,800 L/min) to the Jersey City Sewage Authority sewage system. A central heating plant was installed during the 1980s renovation.[263]

South side

The southern side of Ellis Island, located across the ferry basin from the northern side, is composed of island 2 (created in 1899) and island 3 (created in 1906).[138] The entire southern side of the island is in New Jersey, and the majority of the site is occupied by the hospital buildings. A central corridor runs southward from the ferry building on the west side of the island. Two additional corridors split eastward down the centers of islands 2 and 3.[19][20]

Island 2

Island 2 comprises the northern part of Ellis Island's southern portion. The structures share the same design: a brick facade in Flemish bond, quoins, and limestone ornamentation.[264][265][266] All structures were internally connected via covered passageways.[19][20]

The laundry-hospital outbuilding is south of the ferry terminal, and was constructed in 1900–1901 along with the now-demolished surgeon's house.[128][264] The structure is one and a half stories tall with a hip roof and skylights facing to the north and south.[264] Repaired repeatedly throughout its history,[267] the laundry-outbuilding was last restored in 2002.[268] It had linen, laundry, and disinfecting rooms; a boiler room; a morgue with autopsy room; and quarters for the laundry staff on the second floor.[267]

To the east is the psychopathic ward, a two-story building erected 1906–1907.[127][269][270] The building is the only structure in the hospital complex to have a flat roof, and formerly also had a porch to its south.[270][265] It housed 25 to 30 beds and was intended for the temporary treatment of immigrants suspected of being insane or having mental disorders, pending their deportation, hospitalization, or commitment to sanatoria. Male and female patients were segregated, and there were also a dayroom, veranda, nurse's office, and small pantry on each floor. In 1952 the psychopathic ward was converted into a Coast Guard brig.[265][271]

The main building is directly east of the psychopathic ward. It is composed of three similarly designed structures: from west to east, they are Hospital Building No. 1 (built 1900–1901), the Administration Building (1905–1907), and Hospital Building No. 2 (1908–1909).[128][266] The 3.5-story building no. 1 is shaped like an inverted "C" with two 2.5-story rectangular wings facing southward; the wings contain two-story-tall porches. The administration building is smaller but also 3.5 stories. The 3.5-story building no. 2 is similar to building no. 1, but also has a three-story porch at the south elevation of the central pavilion. All three buildings have stone-stoop entrances on their north facades and courtyards on their south.[266]

Recreation hall

The recreation hall and one of the island's two recreation shelters are located between islands 2 and 3 on the western side of Ellis Island, at the head of the former ferry basin between the two landmasses.[19][20] Built in 1937 in the Colonial Revival style, the structures replaced an earlier recreation building at the northeast corner of island 2.[272][273][274]

The recreation hall is a two-story building with a limestone base, a facade of brick in Flemish bond, a gable roof, and terracotta ornamentation. The first floor contained recreational facilities, while the second floor was used mostly for offices. It contains wings on the north, south, and west. The recreation shelter, a one-story brick pavilion, is located directly to the east.[274][275] A second shelter of similar design was located adjacent to the power plant on the island's north side.[273][275]

Island 3

As part of the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, the contagious disease hospital comprised 17 pavilions, connected with a central connecting corridor. Each pavilion contained separate hospital functions that could be sealed off from each other.[19][20] Most of the structures were completed in 1911.[145][141][276] The pavilions included eight measles wards, three isolation wards, a power house/sterilizer/autopsy theater, mortuary, laboratory, administration building, kitchen, and staff house. All structures were designed by James Knox Taylor in the Italian Renaissance style and are distinguished by red-tiled Ludowici hip roofs, roughcast walls of stucco, and ornamentation of brick and limestone.[276]

The office building and laboratory is a 2.5-story structure located at the west end of island 3.[277] It housed doctors' offices and a dispensary on the first floor, along with a laboratory and pharmacists' quarters on the second floor.[277][278] In 1924, the first floor offices were converted into male nurses' quarters.[279] A one-story morgue is located east of the office building, and was converted to the "Animal House" circa 1919.[280][281]

An "L"-shaped powerhouse and laundry building, built in 1908, is also located on the west side of island 3. It has a square north wing with boiler, coal, and pump rooms, as well as a rectangular south wing with laundry and disinfection rooms, staff kitchen, and staff pantry.[278][282] The powerhouse and laundry also had a distinctive yellow-brick smokestack. Part of the building was converted into a morgue and autopsy room in the 1930s.[282][283]

To the east are the eight measles pavilions (also known as wards A-H), built in phases from 1906 to 1909 and located near the center of island 3. There are four pavilions each to the west and east of island 3's administration building. All of the pavilions are identical, two-story rectangular structures.[278][284][285] Each pavilion floor had a spacious open ward with large windows on three sides and independent ventilation ducts. A hall leading to the connecting corridor was flanked by bathrooms, nurses' duty room, offices, and a serving kitchen.[285]

The administration building is a 3.5-story structure located on the north side of island 3's connecting corridor, in the center of the landmass.[286] It included reception rooms, offices, and a staff kitchen on the first floor; nurses' quarters and operating rooms on the second floor; and additional staff quarters on the third floor.[287] A one-story kitchen with a smokestack is located opposite the administration building to the south.[288][289]

The eastern end of island 3 contained three isolation pavilions (wards I-K) and a staff building.[278] The isolation pavilions were intended for patients for more serious diseases, including scarlet fever, diphtheria, and a combination of either of these diseases with measles and whooping cough. Each pavilion is a 1.5-story rectangular structure. Wards I and K are located to the south of the connecting corridor while ward J is located to the north; originally, all three pavilions were freestanding structures, but covered ways were built between wards I and K and the center corridor in 1914. There were also nurses' quarters in each attic.[278][290][291] The staff building. located at the extreme east end of island 3's connecting corridor, is a 2.5-story building for high-ranking hospital staff. Living and dining rooms, a kitchen, and a library were located on the first floor while bedrooms were located on the second floor.[278][292]

Ferry building

The ferry building is at the western end of the ferry basin, within New Jersey.[20][293] The current structure was built in 1936[294] and is the third ferry landing to occupy the site.[293] It is made of a steel-and-concrete frame with a facade of red brick in Flemish bond, and limestone and terracotta ornamentation, in the Moderne architectural style. The building's central pavilion is mostly one story tall, except for a two-story central section that is covered by a hip roof with cupola. Two rectangular wings are located to the north and south and are oriented east–west.[293][294][295] The south wing was originally reserved for U.S. Customs while the north wing contained a lunchroom and restrooms. A wooden dock extends east from the ferry building.[295] The ferry building is connected to the kitchen and laundry to the north, and the hospital to the south, via covered walkways.[293][295] The structure was completely restored in 2007.[230]

Immigration procedures

By the time Ellis Island's immigration station closed, almost 12 million immigrants had been processed by the U.S. Bureau of Immigration.[88] It is estimated that 10.5 million immigrants departed for points across the United States from the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal nearby.[296][297] Others would have used one of the other terminals along the North River/Hudson River at that time.[298] At the time of closure, it was estimated that closer to 20 million immigrants had been processed or detained at Ellis Island.[299][179]

Initial immigration policy provided for the admission of most immigrants to the United States, other than those with mental or physical disabilities, or a moral, racial, religious, or economic reason for exclusion.[300] At first, the majority of immigrants arriving were Northern and Western Europeans, with the largest numbers coming from the German Empire, the Russian Empire and Finland, the United Kingdom, and Italy.[301] Eventually, these groups of peoples slowed in the rates that they were coming in, and immigrants came in from Southern and Eastern Europe, including Jews. These people immigrated for a variety of reasons including escaping political and economic oppression, as well as persecution, destitution, and violence. Often among these groups were Poles, Hungarians, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks, Greeks, Syrians, Turks, and Armenians.[157]

This woman is wearing her native costume. At times the Island looked like a costume ball with the multiculored, many-styled national costumes.[302]

Immigration through Ellis Island peaked in the first decade of the 20th century.[129][303] Between 1905 and 1914, an average of one million immigrants per year arrived in the United States.[303] Immigration officials reviewed about 5,000 immigrants per day during peak times at Ellis Island.[304] Two-thirds of those individuals emigrated from eastern, southern and central Europe.[305] The peak year for immigration at Ellis Island was 1907, with 1,004,756 immigrants processed,[66] and the all-time daily high occurred on April 17 of that year, when 11,747 immigrants arrived.[306][307] Following the Immigration Act of 1924, which both greatly reduced immigration and allowed processing overseas, Ellis Island was only used by those who had problems with their immigration paperwork, as well as displaced persons and war refugees.[158][159][308] This affected both nationwide and regional immigration processing: only 2.34 million immigrants passed through the Port of New York from 1925 to 1954, compared to the 12 million immigrants processed from 1900 to 1924.[i][303] Average annual immigration through the Port of New York from 1892 to 1924 typically numbered in the hundreds of thousands, though after 1924, annual immigration through the port was usually in the tens of thousands.[303]

Inspections

Medical inspection

Beginning in the 1890s, initial medical inspections were conducted by steamship companies at the European ports of embarkation; further examinations and vaccinations occurred on board ship during the voyage to New York.[310] On arrival at the port of New York, ships halted at the New York state quarantine station near the Narrows. Those with serious contagious diseases (such as cholera and typhus) were quarantined at Hoffman Island or Swinburne Island, two artificial islands off the shore of Staten Island to the south.[311][312][313] The islands ceased to be used for quarantine by the 1920s due to the decline in inspections at Ellis Island.[310] For the vast majority of passengers, since most transatlantic ships could not dock at Ellis Island due to shallow water, the ships unloaded at Manhattan first, and steerage passengers were then taken to Ellis Island for processing. First- and second-class passengers typically bypassed the Ellis Island processing altogether.[314]

To support the activities of the United States Bureau of Immigration, the United States Public Health Service operated an extensive medical service. The medical force at Ellis Island started operating when the first immigration station opened in 1892, and was suspended when the station burned down in 1897.[315] Between 1897 and 1902, medical inspections took place both at other facilities in New York City and on ships in the New York Harbor.[316] A second hospital called U.S. Marine Hospital Number 43 or the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital was built in 1902 and operated through 1930.[160][161][162] Uniformed military surgeons staffed the medical division, which was active in the hospital wards, the Battery's Barge Office, and Ellis Island's Main Building.[317][318] Immigrants were brought to the island via barge from their transatlantic ships.[319][320]

A "line inspection" was conducted in the main building. In the line inspection, the immigrants were split into several single-file lines, and inspectors first checked for any visible physical disabilities.[318][320][321] Each immigrant was inspected by two inspectors: one to catch any initial physical disabilities, and another to check for any other ailments that the first inspector did not notice.[321] The doctors then observed immigrants as they walked, to determine any irregularities in their gait. Immigrants were asked to drop their baggage and walk up the stairs to the second floor.[322][320][321]

The line inspection at Ellis Island was unique because of the volume of people it processed, and as such, used several unconventional methods of medical examination.[318][323] For example, after an initial check for physical disabilities, inspectors used special forceps or the buttonhook to examine immigrants for signs of eye diseases such as trachoma.[324] Following each examination, inspectors used chalk to draw symbols on immigrants who were suspected to be sick.[325][319][323] Some immigrants supposedly wiped the chalk marks off surreptitiously or inverted their clothes to avoid medical detention.[322] Chalk-marked immigrants and those with suspected mental disabilities were then sent to rooms for further inspection, according to a 1917 account.[319]

The symbols used for chalk markings were:[325][319]

Primary inspection

Once immigrants had completed and passed the medical examination, they were sent to the Registry Room to undergo what was called primary inspection. This consisted of interrogations conducted by U.S. Immigrant Inspectors to determine if each newcomer was eligible for admission. In addition, any medical certificates issued by physicians were taken into account. Aside from the U.S. immigrant inspectors, the Bureau of Immigration work force included interpreters, watchmen, matrons, clerks and stenographers.[326] According to a reconstruction of immigration processes in 1907, immigrants who passed the initial inspections spent two to five hours at Ellis Island to do these interviews. Arrivals were asked a couple dozen questions, including name, occupation, and the amount of money they carried. The government wanted to determine whether new arrivals would be self-sufficient upon arrival, and on average, wanted the immigrants to have between $18 and $25 (worth between $589 and $818 as of 2023[j]).[327] Some immigrants were also given literacy tests in their native languages, though children under 16 were exempt. The determination of admissibility was relatively arbitrary and determined by the individual inspector.[326]

U.S. Immigrant Inspectors used some other symbols or marks as they interrogated immigrants in the Registry Room to determine whether to admit or detain them, including:[325]

- SI – Special Inquiry

- IV – Immigrant Visa

- LPC – Likely or Liable to become a Public Charge

- Med. Cert. – Medical certificate issued

Those who were cleared were given a medical certificate or an affidavit.[320] According to a 1912 account by physician Alfred C. Reed, immigrants were medically cleared only after three on-duty physicians signed an affidavit.[323] Those with visible illnesses were deported or held in the island's hospital.[327] Those who were admitted often met with relatives and friends at the Kissing Post, a wooden column outside the registry room.[328]

Between 1891 and 1930, Ellis Island reviewed over 25 million attempted immigrants, of which 700,000 were given certificates of disability or disease and of these 79,000 were barred from entry. Approximately 4.4% of immigrants between 1909 and 1930 were classified as disabled or diseased, and one percent of immigrants were deported yearly due to medical causes. The proportion of "diseased" increased to 8.0% during the Spanish flu of 1918–1919.[329] More than 3,000 attempted immigrants died in the island's hospital.[327] Some unskilled workers were deemed "likely to become a public charge" and so were rejected; about 2% of immigrants were deported.[327] Immigrants could also be excluded if they were disabled and previously rejected; if they were Chinese, regardless of their citizenship status; or if they were contract laborers, stowaways, and workaways.[326] However, immigrants were exempt from deportation if they had close family ties to a U.S. permanent resident or citizen, or if they were seamen.[330] Ellis Island was sometimes known as the "Island of Tears" or "Heartbreak Island" for these deportees.[331] If immigrants were rejected, appeals could be made to a three-member board of inquiry.[332]

Mass detentions and deportations

Ellis Island's use as a detention center dates from World War I, when it was used to house those who were suspected of being enemy soldiers.[140][149][148][333] During the war, six classes of "enemy aliens" were established, including officers and crewmen from interned ships; three classes of Germans; and suspected spies.[334] After the American entry into World War I, about 1,100 German and Austrian naval officers and crewmen in the Ports of New York and New London were seized and held in Ellis Island's baggage and dormitory building.[333] A commodious stockade was built for the seized officers.[335] A 1917 New York Times article depicted the conditions of the detention center as being relatively hospitable.[336]

Anti-immigrant sentiments developed in the U.S. during and after World War I, especially toward Southern and Eastern Europeans who were entering the country in large numbers.[337][338] Following the Immigration Act of 1924, primary inspection was moved to New York Harbor, and Ellis Island only hosted immigrants that were to be detained or deported.[158][159] After the passage of the 1924 act, the Immigration Service established multiple classes of people who were said to be "deportable". This included immigrants who entered in violation of previous exclusion acts; Chinese immigrants in violation of the 1924 act; those convicted of felonies or other "crimes of moral turpitude"; and those involved in prostitution.[339]

During and immediately following World War II, Ellis Island was used to hold German merchant mariners and "enemy aliens"—Axis nationals detained for fear of spying, sabotage, and other fifth column activity.[340] When the U.S. entered the war in December 1941, Ellis Island held 279 Japanese, 248 Germans, and 81 Italians removed from the East Coast.[341] Unlike other wartime immigration detention stations, Ellis Island was designated as a permanent holding facility and was used to hold foreign nationals throughout the war.[342] A total of 7,000 Germans, Italians and Japanese were ultimately detained at Ellis Island.[66]

The Internal Security Act of 1950 barred members of communist or fascist organizations from immigrating to the United States. Two notable communists known to have been imprisoned on Ellis Island include Billy Strachan, a pioneer of black civil rights in Britain, and Ferdinand Smith who co-founded the first desegregated union in the history of the United States.[343] Ellis Island saw detention peak at 1,500, but by 1952, after changes to immigration laws and policies, only 30 to 40 detainees remained.[19][66] One of the last detainees was the Indonesian Aceh separatist Hasan di Tiro who, while a student in New York in 1953, declared himself the "foreign minister" of the rebellious Darul Islam movement and was subsequently stripped of his Indonesian citizenship and held as an "illegal alien".[344]

Eugenic influence

When immigration through Ellis Island peaked, eugenic ideals gained broad popularity and made heavy impact on immigration to the United States by way of exclusion of disabled and "morally defective" people. Eugenicists of the late 19th and early 20th century believed human reproductive selection should be carried out by the state as a collective decision.[345] For many eugenicists, this was considered a patriotic duty as they held an interest in creating a greater national race. Henry Fairfield Osborn's opening words to the New York Evening Journal in 1911 were, "As a biologist as well as a patriot...," on the subject on advocating for tighter inspections of immigrants of the United States.[346]

Eugenic selection occurred on two distinguishable levels:

- State/Local levels which handles institutionalization and sterilization of those considered defective as well as the education of the public; marriage laws; and social pressures such as fitter-family and better-baby contests.[347]

- Immigration control, the screening of immigrants for defects, was notably supported by Harry Laughlin, superintendent of the Eugenics Record Office from 1910 to 1939, who stated that this was where the "federal government must cooperate."[348]

At the time, it was a broadly popular idea that immigration policies had ought to be based on eugenics principles in order to help create a "superior race" in America. To do this, defective persons needed to be screened by immigration officials and denied entry on the basis of their disability.[320]

During the line inspection process, ailments were marked using chalk.[325][319] There were three types of illness that were screened for:

- Physical – people who had hereditary or acquired physical disability. These included sickness and disease, deformity, lack of limbs, being abnormally tall or short, feminization, and so forth.[320][346] This was covered by most of the chalk indications.[325][319]

- Mental – people who showed signs or history of mental illness and intellectual disability. These included "feeble-mindedness", "imbecility", depression, and other illnesses that stemmed from the brain such as epilepsy and cerebral palsy.[320][349]

- Moral – people who had "moral defects". These included homosexuals, paraphiliacs, criminals, the impoverished, and other "degenerates" who deviated from what American society then considered normal.[350]

The people with moral or mental disability, who were of higher concern to officials and under the law, were required to be excluded from entry to the United States. Persons with physical disability were under higher inspection and could be turned away on the basis of their disability. Much of this came in part of the eugenicist belief that defects are hereditary, especially those of the moral and mental nature those these are often outwardly signified by physical deformity as well.[345] As Chicago surgeon Eugene S. Talbot wrote in 1898, "crime is hereditary, a tendency which is, in most cases, associated with bodily defects."[351] Likewise, George Lydston, a medicine and criminal anthropology professor, wrote in 1906 that people with "defective physique" were not just criminally associated but that defectiveness was a primary factor "in the causation of crime."[352]

Leadership

Within the U.S. Bureau of Immigration, there were fifteen commissioners assigned to oversee immigration procedures at the Port of New York, and thus, operations at Ellis Island. The twelve commissioners through 1940 were political appointees selected by the U.S. president; the political parties listed are those of the president who appointed each commissioner. One man, William Williams, served twice as commissioner.[70][353]

- 1890–1893 John B. Weber (Republican)[70][353][354]

- 1893–1897 Joseph H. Senner (Democrat)[70][353]

- 1898–1902 Thomas Fitchie (Republican)[70][353]

- 1902–1905 William Williams (Republican)[70][353][355]

- 1905–1909 Robert Watchorn (Republican)[70][353]

- 1909–1913 William Williams (Republican)[70][353]

- 1914–1919 Frederic C. Howe (Democrat)[70][353]

- 1920–1921 Frederick A. Wallis (Democrat)[70][353]

- 1921–1923 Robert E. Tod (Republican)[70][353]

- 1923–1926 Henry H. Curran (Republican)[70][353]

- 1926–1931 Benjamin M. Day (Republican)[353][356]

- 1931–1934 Edward Corsi (Republican)[70][353]

- 1934–1940 Rudolph Reimer (Democrat)[70][353]

The final three commissioners held a non-partisan position of "district director". The district directors were:[357]

- 1933–1942 Byron H. Uhl[358][357]

- 1942–1949 W. Frank Watkins[359][360][357]

- 1949–1954 Edward J. Shaughnessy[70][357][360]

Name-change myth

According to a myth, immigrants were unwillingly forced to take new names, though there are no historical records of this.[361][362] Rather, immigration officials simply used the names from the manifests of steamship companies, which served as the only immigration records for those entering the United States. Records show that immigration officials often actually corrected mistakes in immigrants' names, since inspectors knew three languages on average and each worker was usually assigned to process immigrants who spoke the same languages.[361][362][363]

Many immigrant families Americanized their surnames afterward, either immediately following the immigration process or gradually after assimilating into American culture.[362] Because the average family changed their surname five years after immigration, the Naturalization Act of 1906 required documentation of name changes.[362][363] The myth of name changes at Ellis Island still persists, likely because of the perception of the immigration center as a formidable port of arrival.[362]

Current use

The island is administered by the National Park Service,[364] though fire protection and medical services are also provided by the Jersey City Fire Department.[254] In extreme medical emergencies, there is also a helicopter for medical evacuations.[365]

Museum and Wall of Honor

The Ellis Island Immigration Museum opened on September 10, 1990,[225] replacing the American Museum of Immigration on Liberty Island, which closed in 1991.[366] The museum contains several exhibits across three floors of the main building, with a first-floor expansion into the kitchen-laundry building.[367] The first floor houses the main lobby within the baggage room, the Family Immigration History Center, Peopling of America, and New Eras of Immigration.[368] The second floor includes the registry room, the hearing room, Through America's Gate, and Peak Immigration Years.[369] The third floor contains a dormitory room, Restoring a Landmark, Silent Voices, Treasures from Home, and Ellis Island Chronicles, as well as rotating exhibits.[370] There are also three theaters used for film and live performances.[367] The third floor contains a library, reading room, and "oral history center", while the theaters are located on the first and second floors. There are auditoriums on all floors.[226][371] On the ground floor is a gift shop and bookstore, as well as a booth for audio tours.[226][368][371]

In 2008, by act of Congress and despite opposition from the NPS, the museum's library was officially renamed the Bob Hope Memorial Library in honor of one of the station's most famous immigrants, comedian Bob Hope.[372] On May 20, 2015, the Ellis Island Immigration Museum was officially renamed the Ellis Island National Museum of Immigration, coinciding with the opening of the new Peopling of America galleries in the first floor of the kitchen-laundry building.[373] The expansion tells the entire story of American immigration, including before and after the periods that Ellis Island processed immigrants.[373][374][255]

The Wall of Honor outside of the main building contains a list of 775,000 names inscribed on 770 panels, including slaves, Native Americans, and immigrants that were not processed on the island.[375][228] The Wall of Honor originated in the late 1980s as a means to pay for Ellis Island's renovation, and initially included 75,000 names.[375][376] The wall originally opened in 1990 and consisted of copper panels.[228][223] Shortly afterward it was reconstructed in two phases: a circular portion that started in 1993, and a linear portion that was built between 1998 and 2001.[223] The Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation requires potential honorees to pay a fee for inscription.[377] By 2019, the wall was mostly full and only five panels remained to be inscribed.[228]

NPS offers several educational opportunities, including self-guided tours and immersive, role-playing activities.[378][379] These educational programs and resources cater to over 650,000 students per year and aim to promote discussion while fostering a climate of tolerance and understanding.[379]

South side

The south side of the island, home to the Ellis Island Immigrant Hospital, is abandoned and remains unrenovated.[380][381] Disagreements over its proposed use have precluded any development on the south side for several decades.[222] The NPS held a competition for proposals to redevelop the south side in 1981 and ultimately selected a plan for a conference center and a 250-to-300-room Sheraton hotel on the site of the hospital.[217][382] In 1985, while restoration of the north side of Ellis Island was underway, Interior Secretary Donald P. Hodel convened a long-inactive federal commission to determine how the south side of Ellis Island should be used.[383] Though the hotel proposal was dropped in 1986 for lack of funds,[384] the NPS allowed developer William Hubbard to redevelop the south side as a convention center, though Hubbard was not able to find investors.[385] The south side was proposed for possible future development even through the late 1990s.[34][386]

Save Ellis Island led preservation efforts of the south side of the island. The ferry building remains only partially accessible to the general public.[387] As part of the National Park Service's Centennial Initiative, the south side of the island was to be the target of a project to restore the 28 buildings that have not yet been rehabilitated.[388]

In 2014, the NPS started offering guided public tours of the south side as part of the "Hard Hat Tour", which charges an additional fee that is used to support Save Ellis Island's preservation efforts.[47] The south side also includes "Unframed – Ellis Island", an art installation by the French street artist JR, which includes murals of figures who would have occupied each of the respective hospital buildings.[389][390]

Cultural impact

Commemorations