Clayton Bay

| Clayton Bay South Australia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 35°29′44″S 138°54′40″E / 35.495488°S 138.911048°E[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Population | 386 (UCL 2021)[2] | ||||||||||||||

| Established | 1858 (town) 31 August 2000 (locality)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Postcode(s) | 5256 | ||||||||||||||

| Elevation | 70 m (230 ft)[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Time zone | ACST (UTC+9:30) | ||||||||||||||

| • Summer (DST) | ACDT (UTC+10:30) | ||||||||||||||

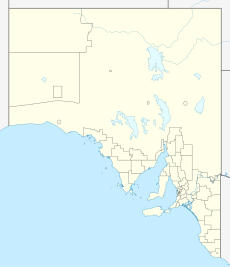

| Location | |||||||||||||||

| LGA(s) | Alexandrina Council | ||||||||||||||

| Region | Fleurieu and Kangaroo Island[3] | ||||||||||||||

| State electorate(s) | Hammond[4] | ||||||||||||||

| Federal division(s) | Mayo | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

Clayton Bay is a town in South Australia located on Lake Alexandrina and Lower Murray River, part of the lower lakes and Coorong region at the end of the Murray River System. The town is located north of the north-east tip of Hindmarsh Island about 87 kilometres (54 mi) from Adelaide and 30.7 kilometres (19 mi) by road from Goolwa.

In 2008, the name of Clayton was officially changed to Clayton Bay by application to the Alexandrina Council and the South Australian Government to avoid confusion with Clayton, Victoria.[1]

Description

The wetlands, waters, foreshore and wider environs at Clayton Bay host spectacular sunsets and area attracting national and international environmentalists, ornithologists, bird watchers, photographers, artists, botanists, anthropologists, astronomers and those engaged in ecotourism and water based activities, particularly sailing (popular due to seasonal high wind speeds).

Experience is needed for water activities as the area is very exposed to the wind and the shallow nature of Lake Alexandrina and Lower Lakes creates large choppy waves.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12] Waters around the area are classified as either 'protected' and 'semi-protected' waters by the South Australian Government. Appropriate safety equipment according to those classifications is required under legislation for all boating activities.[13] Anyone aboard a motorised boat less than 4.8 metres long must wear a life jacket of all times, and children aged 12 or younger must do so in open areas of boats up to 12 metres in length.

International Significance

Clayton Bay is included within the Coorong, Lower Murray, Lower Lakes, Murray Mouth, Lake Alexandrina and Lake Albert wetland, as one of Australia's most important wetland areas.

Australia designated the site, covering approximately 140,500 ha in South Australia, as a Wetland of International Importance[14] under the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands in 1985. The Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland RAMSAR site:

...encompasses the Coorong National Park, Lake Alexandrina, Lake Albert, and tributaries, up to +0.85m AHD. Where unalienated crown land, DEWNR reserve or crown land under licence exists adjacent to the waters edge the boundary has been extended to include this cadastral parcel. The site excludes all privately owned fringing wetlands around the edge of the lakes except for land subject to inundation in Clayton Bay, Marshall Bight and Tookayerta Creek.[15][16]

Wetlands in Clayton Bay and surrounds are nesting and breeding grounds for a large variety of migratory birds.[17][18][19][20] Under RAMSAR criteria the wetlands supports one or more percent of the population of the following species:

- Australian Pelican (Pelecanus conspicillatus)

- Australasian bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)

- Australian Shelduck (Tadornis tadornoides)

- Australian Painted Snipe (Rostratula australis benghalensis)

- Banded Stilt (Cladorhynchus leucocephalus)

- Black Swan (Cygnus atratus)

- Chestnut Teal (Anas castanea)

- Curlew Sandpiper (Calidris ferruginea)

- Greater Crested Tern (Thalasseus bergii)

- Grey Teal (Anas gracilis)

- Hoary-headed Grebe (Poliocephalus poliocephalus)

- Red-capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillus)

- Red-necked Stint (Calidris ruficollis)

- Sharp-tailed Sandpiper (Calidris acuminata)

- Silver Gull (Larus novaehollandiae)

- Whiskered Tern (Chlidonias hybridus fluviatilis)

- Fairy Tern (Sterna nereis nereis)

- Australian Painted Snipe (Rostratula aust)

- Red-capped Plover (Charadrius ruficapillu)

- Australasian Swamphen (Porphyrio melanotus)

- Australasian Shoveler (Anas rhynchotis)

Many other birds can be seen in the region including:

- Australian magpie (Gymnorhina tibicen)

- Willie Wagtail (Rhipidura leucophrys)

- Long-billed Corella (Cacatua tenuirostris)

- Galah (Eolophus roseicapilla)

- Welcome Swallow (Hirundo neoxena)

- Pied Butcher Bird (Cracticus nigrogularis)

- Tawny Frogmouth (Eurostopodus argus)

- Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) and more.[21]

The area is inhabited by common, threatened and/or endangered species of mammals, amphibians, and reptiles. These include:

- Swamp Rat (Rattus lutreolus),

- Murray Turtle (Emydura macquarii)

- Yellow-bellied Water Skink (Eulamprus heatwolei),

- Eastern long-necked turtles (Chelodina longicollis),

- Eastern Brown Snakes (Pseudonaja textilis)

- Tiger Snakes (Notechis scutatus)

- Southern Bell frogs (Ranoidea raniformis)[22][23]

There are populations of kangaroos, sleepy lizards (Tiliqua rugosa) and short-beaked echidnas (Tachyglossus aculeatus) within the town and environs.

Plant species include:

- River club rush (Schoenoplectus validus)

- Sandhill Greenhood Orchid (Pterostylis arenicola)

- Silver Daisy-bush (Olearia pannosa ssp pannosa)

- Diverse reed beds

- Freshwater herblands (e.g. Triglochin sp.)

- Cutting Grass (Gahnia filum) sedgeland,

- Swamp Paperbark (Melaleuca halmaturorum)

- Lignum shrubland (Muehlenbeckia florulenta)

- Samphire chenopod shrubland (including Tecticornia pergranulata ssp. Pergranulata, Suaeda australis, Sarcocornia quinqueflora and Juncus kraussi).[24][25]

The Ramsar site supports approximately 43 fish species[26] including:

- Basinendemic Yarra Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca obscura),

- Small-mouthed Hardyhead (Atherinosoma microstoma)

- Murray Cod (Maccullochella peelii peelii)

- Murray Hardyhead (Craterocephalus fluviatilis)

- Lagoon Goby (Tasmanogobius lasti)

- Tamar Goby (Afurcagobius tamarensis).

- Freshwater Catfish (Tandanus tandanus)

- Southern Purple-spotted Gudgeon (Morgurnda adspersa)

- Southern Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca australis)

- Yarra Pygmy Perch (Nannoperca obscura)

- Flat-headed Gudgeon (Philypnodon grandiceps)

- Dwarf Flat-headed Gudgeon (Philypnodon macrostomus)

- Unspecked Hardyhead (Craterocephalus stercusmuscarum fulvus)

- Congolli (Pseudophritis urvillii)

- Pouched Lamprey (Geotria australis)

- Short-headed Lamprey (Mordacia mordax)

- Mountain Galaxias (Galaxias olidus)

- Estuary Perch (Macquaria colonorum)

- Short-finned Eel (Anguilla australis)[27]

History

Aboriginal history

The Ngarrindjeri peoples are the Aboriginal Australian Owners of the lower Murray River, eastern Fleurieu Peninsula, and the Coorong of the southern-central area of the state of South Australia. The Ngarrindjeri consist of several distinct if closely related groups, including the Jarildekald, Tanganekald, Meintangk and Ramindjeri,[28] who began to form a unified cultural bloc after Aboriginal peoples were forcibly removed to Raukkan, South Australia (formerly Point McLeay Mission).[29]

Archaeology, particularly in excavations conducted at Roonka Flat, (which affords an outstanding sites for investigating "pre–European contact Aboriginal burial populations in Australia,") have revealed that the traditional lands of the Ngarrindjeri have been inhabited since the Holocene period, beginning around 8,000 B.C. down to around 1840 CE.[30]

For thousands of years, the Lower Murray, Lower Lakes and Coorong region was one of the most densely populated areas of Australia, and the land (ruwe or ruwar) and waterways were home to thousands of Ngarrindjeri peoples.[31] Ngarrindjeri lived in communities in the ruwe.[32] Everything Ngarrindjeri needed was present–clean waters, foods, medicines, shelter and warmth.[33]

Ngarrindjeri Self Determination, Control and Management

Ngarrindjeri peoples and supporters have challenged and partnered with the South Australian Government for decades,[34] including its natural resource management representatives, over questions of justice, agency, control, sovereignty and the decolonisation of existing and long-standing relationships.[35][36]

Ngarrindjeri led the development of the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth (CLLMM) Ngarrindjeri Partnerships and Murrundi (Riverine) Recovery Projects.[37] In 2002, the Alexandrina Council made an agreement with the Ngarrindjeri Nation. The agreement included a series of commitments to work together and offers an expression of sorrow and apology to the Ngarrindjeri peoples. It is known as the Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan (KNY) Agreement.

In 2007, the Ngarrindjeri Nation launched the Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri Sea Country and Culture (the 'NNYR Plan') stating the Ngarrindjeri Vision for Country

Our Lands, Our Waters, Our People, All Living Things are connected. We implore people to respect our Ruwe (Country) as it was created in the Kaldowinyeri (the Creation). We long for sparkling, clean waters, healthy land and people and all living things. We long for the Yarluwar-Ruwe (Sea Country) of our ancestors. Our vision is all people Caring, Sharing, Knowing and Respecting the lands, the waters and all living things.[35]

After lengthy negotiations with the South Australian Government entered into the Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement: Listen to Ngarrindjeri Speaking Agreement in 2009.[38][39]

Native Title

The native title rights and interests of the Ngarrindjeri people were recognised in Ngarrindjeri and Others Native Title Claim on 14 December 2017. The determination granted the Ngarrindjeri people rights including the right to access and move around the Native Title Land, hunt, fish and gather, share and exchange, use Natural Water Resources, cook and light fires for ceremonial purposes, engage in cultural activities and protect cultural sites. All waterways and several parcels of land within Clayton Bay are within Native Title legislation with any vegetation clearance or development requiring approval through the Registered Native Title Body Corporate.[40][1]

European history

In 1829, Governor Darling commissioned Captain Charles Sturt to follow the Murrumbidgee, which had been discovered by Hume and Hovell. On 3 November 1829, Sturt left Sydney to assume command of the expedition that eventually turned itself into the famous Murray River Voyage. On 26 December 1829, his team assembled a 25-foot whaleboat and built a log skiff for carrying stores and only two oars. This work was supervised by a carpenter, named Mr Clayton. The boat party departed from the Lachlan River on 7 January 1830. The crew, besides Sturt and Macleay included soldiers, Harris, Hopkinson, and Frasier and convicts, Mulholland, Macnamee, and Clayton.[41]

In 1830 the first exploratory expedition reached the Ngarrindjeri lands and Sturt and crew noted Ngarrindjeri were already familiar with firearms.[42][43] Ngarrindjeri told them that the ocean was nearby and Sturt sailed into a lake which Sturt named Alexandrina. Around 9 February 1830, Sturt sighted seagulls. A few days later, they found the point where the Murray flowed into the sea.[44]

In the 1840s, Dr John Rankine operated his own ferry service from the Clayton Bay to Hindmarsh Island, mainly transporting his sheep and workers and called 'Rankine's Ferry.' The town of Clayton was later named by Governor MacDonnell in 1858. Land allotments were offered for sale in 1859 in the area informally known as 'Old Clayton.' Clayton Bay was subdivided as a settlement in 1859 and a store, post office and a few dwellings were established. In 1969, the Clayton subdivision was established and other developments north of Alexandrina Drive, were developed between 1985 and 2009 creating the current town. A well-known yabby restaurant operated from 1974 until approximately 2009.[45][46][47]

Strategically, Clayton Bay is an important place as the channel separating it from Hindmarsh Island is at its narrowest. The 2000s Australian drought arose from very low flows to the Lower Murray (over Lock 1) resulting in the lowest water levels in over 90 years of records.[48] The lowest water levels during the extreme low flow period were reached in April 2009, and represented a 64% and 73% reduction in the volume of Lakes Alexandrina and Albert respectively. The low water levels and inflows meant there was no outflow from the lake system during the extreme low flow period. During this period the lake levels fell below mean sea level (approximately +0.2 m AHD) downstream of the barrages, reversing the usual positive hydraulic gradient from the lake to the sea. The seawater intrusion, lack of flushing, evapoconcentration and increased resuspension resulted in severe water quality impacts[48] Exposure and oxidation of acid sulfate soils due to falling water levels from 2007 to 2009 in the Lower River and Lower Lakes also resulted in acidification of soils, lake and groundwater.[49][50][51] Large scale engineering interventions were undertaken to prevent further acidification, including constructions at Clayton Bay and pumping of water to prevent exposure and acidification of Lake Albert.[52] Management of acidification in the Lower Lakes was also undertaken using aerial limestone dosing.[53][54] The South Australian government erected a barrage (known as a restrictor flow bund) at Clayton Bay to stop the flow of Lake Alexandrina waters towards the mouth of the Murray River[55] The River, Lakes and Coorong Action Group (chaired by Prof. Diane Bell and including Henry and Gloria Jones) vigorously campaigned for the removal of the 'Clayton regulator' to restore water flows. The regulator was removed in 2011.[56][57][58]

Jones' Lookout (named after Henry Jones, local fisherman and environmentalist) was opened in 2009 and is located on the concrete plinth where a former water tower once stood on a clifftop. The mosaic design by artist, Michael Tye consists of a compass rose formed by intersecting ripples.[59] The tiles used for the mosaic are hand-cut, vitrified porcelain tiles, surrounded by tiling of unglazed quarry tiles. The mosaic is a compass made of intersecting ripples of mainly blue tiles, with the colours at the north point depicting sunset on the water. Each of the compass points names a key location in the direction and their distances from Clayton Bay, and from the platform there are views of Lake Alexandrina and the Lower Lakes. North point is emphasised by the colours of sunset on the water. The work also includes swamp hen footprints to an area of concrete that borders the tiling (the work was commissioned during the 2000s Australian Drought when water levels were extremely low and the purple swamp hen (Porphyrio melanotus) disappeared from the area, leaving nothing but footprints).

Environmental threats and action

Clayton Bay is part of an internationally significant Ramsar wetland area and a highly fragile ecological setting with Indigenous cultural heritage sites. The wetlands contribute to the filtration and quality of water flowing into the Lower Lakes.[60]

Serious environmental threats are posed by:

- climate change,

- water extraction,

- drought,

- reedbed clearing, reduction or dispersal of reedbeds (i.e. creating gaps between reedbeds),

- touristic activities (e.g. unsustainable numbers of tourists, wakeboarding, waterskiing, jet skis, powerboats),

- human intrusions and activity,

- noise and light pollution,

- vehicular use,

- introduction of contaminants,

- introduced vegetation (e.g. esp. kikuyu grass and similar invasive species into reed beds),

- the removal of native vegetation, and

- Introduced and feral animals.

The beauty of the area attracts numerous tourists whose numbers and activities may not be able to be sustained. Inappropriate human activities causing environmental damage to the wetlands are difficult to regulate as there are several public boat ramps in the town and the Alexandrina Council have leased areas adjacent to the wetlands to touristic, for profit bodies.

European Carp introduced to the Murray-Darling Basin in the 1920s pose a major threat.[61] An invasive widespread fish species, they are highly adaptable and have biological features that allow populations to increase rapidly. Carp contribute to environmental degradation through reduction in water quality, river bank damage and may contribute to algae blooms. The increased spread of carp and its impact on freshwater habitat has come at the expense of native fish species and aquatic vegetation.[62] Australian scientists have determined that using the naturally occurring carp herpesvirus (Cyprinid herpesvirus-3: CyHV-3, sometimes referred to as KHV) a biological control agent could significantly reduce the number of carp.[63] The combination of a biological control mechanism, and an improved environmental flow regime may impact the likelihood of a positive future for native fish, although there is still ongoing debates.[64][65][66] European carp are considered a pest species and highly prevalent at Clayton Bay. Carp if caught must not be returned to it to the water, be destroyed and disposed of.

River regulation, water extraction and droughts have reduced the total volume of water available resulting in a substantial decline in the waterways. Work by Ngarrindjeri Native Title holders, local residents and the Alexandrina Council attempt to balance touristic activities, strongly promoting ecotourism practices, seeking to preserve and protect cultural heritage sites, prevent inappropriate developments and activities and preserve and rehabilitate the environment, increase wetland areas, maintain and work to increase water flows along the catchment and increase water quality.

Many Clayton Bay residents have adopted stewardship environmental roles and are involved in:

- citizen science[67] including annual bird and amphibian counts, vegetation surveys, temperature and wind speed measurements, astronomical observations,

- advocating and active involvement in the preservation, restoration and revitalization of the wetlands,

- turtle rescue programs,[68]

- overseeing the preservation of remnant vegetation,

- revegetation programs[69]

- interventions to decrease the spread of Australian tubeworm (Ficopomatus enigmaticus),[70]

- the development of walking trails[71] and wetland boardwalks,

- bird and fauna rescue and return to native habitats,

- protecting the breeding grounds of Eastern long-necked turtles (Chelodina longicollis) which are vulnerable from recreational activity, noise, environmental degradation, infestations of Australian tubeworm (Ficopomatus enigmaticus)[72] and predators including foxes and cats. (Note: the Alexandrina Council offer cat traps to deal with issues arising from feral or unidentified cats),.[73]

- a program to raise nationally threatened Southern Bell frogs (Ranoidea raniformis) in captivity to be released back into the wetlands operates within the town.[74][75][76]

- local seed bank and land care programs, and

- adopting a dark sky policies in collaboration with the Alexandrina Council (the town has only five street lights operating).[77]Clayton Bay Lighting

Notable residents

- Annabelle Collett[78][79][80](Artist)

- Deane Fergie[81][82] (Anthropologist)

- Elizabeth Grant (Architect/Anthropologist)

- Gloria Jones[47] (Environmentalist/Restaurateur/Fisherman/Activist)

- Henry Jones[83] (Environmentalist/Fisherman/Activist)

- Rob Lucas[84] (Anthropologist)

References

- ^ a b c d "Search result for "Clayton Bay, LOCB" with the following datasets selected - "Suburbs and Localities", "Counties", "Government Towns", "Local Government Areas", "SA Government Regions" and "Gazetteer"". Location SA Map Viewer. South Australian government. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Australian Bureau of Statistics (28 June 2022). "Clayton Bay (urban centre and locality)". Australian Census 2021.

- ^ "Fleurieu Kangaroo Island SA Government region" (PDF). The Government of South Australia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2019. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ "Hammond (Electoral district profile)". ELECTORAL COMMISSION SA. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ Fatal Boat Accident on Lake Alexandrina. (22 January 1879). Queanbeyan Age (NSW : 1867 – 1904), p. 4. Retrieved 25 January, 202o, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article30674905

- ^ TWO MEN DROWNED IN LAKE ALEXANDRINA. (24 April 1885). The South Australian Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1858 – 1889), p. 5. Retrieved 25 November 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article36305038

- ^ LAKE ALEXANDRINA DROWNING ACCIDENT. (21 April 1924). The Register (Adelaide, SA : 1901 – 1929), p. 11. Retrieved 25 November 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article64210174

- ^ DROWNED IN LAKE ALEXANDRINA. (24 August 1903). The Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 – 1954), p. 6. Retrieved 25 November 2019, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article197221060

- ^ SIXTEEN HOURS IN LAKE ALEXANDRINA. (25 March 1898). The Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1889 – 1931), p. 5. Retrieved 25 November 2021, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article35109317

- ^ Man missing on lake (28 September 1983). Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 – 1986), p. 3. Retrieved 25 November 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article186021741

- ^ FOUR MEN DROWNED (14 March 1939). Northern Standard (Darwin, NT : 1921 – 1955), p. 2. Retrieved 25 November, 202o, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article49454123

- ^ Five dead, one missing in water (24 August 1987). The Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 – 1995), p. 3. Retrieved 19 November 2018, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132154839

- ^ "Carrying suitable safety equipment". South Australian Government. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016.

- ^ Mosley, L., Ye, Q., Shepherd, S., Hemming, S., & Fitzpatrick, R. (2019). Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth Region (Yarluwar-Ruwe). University of Adelaide Press on behalf of the Royal Society of South Australia.

- ^ "2013 Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS). Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Coorong, and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert Wetland" (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia Department of Environment. Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2011.

- ^ "Register of the National Estate (Non-statutory archive), Tolderol Game Reserve, Langhorne Creek, SA, Australia". Commonwealth of Australia (C of A), Department of the Environment. 21 October 1980. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- ^ O’Connor, J, Rogers, D & Pisanu, P (2012) Monitoring the Ramsar Status of the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth: a case study using birds. South Australian Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Adelaide.

- ^ Paton, D (1997) Bird ecology in the Coorong and Lower lakes region, in River Murray Barrages Environmental Flows: An evaluation of environmental flow needs in the Lower Lakes and Coorong, pp 106- 109. Jensen, A., Good, M., Tucker, P. & Long, M. (eds). Report to the Murray-Darling Basin Commission, Canberra.

- ^ Paton, D & Bailey, C (2010) Condition monitoring of the Lower Lakes, Coorong and Murray Mouth Icon Site: Waterbirds using the Coorong and Murray Mouth estuary in 2010. School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Adelaide

- ^ Wainwright, P & Christie, M (2008) Wader surveys at the Coorong and S.E. coastal lakes, South Australia, February 2008. The Stilt 54: 31-47.

- ^ "Murray River National Park bird checklist – Avibase – Bird Checklists of the World". avibase.bsc-eoc.org.

- ^ Mason K (2010) Southern bell frog (Litoria raniformis) inventory of Lake Alexandrina, Lake Albert and tributaries. SA Murray-Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board, Murray Bridge.

- ^ Mason, K & Hillyard, K (2011) Southern Bell Frog (L. raniformis) monitoring in the Lower Lakes. Goolwa River Murray Channel, tributaries of Currency Creek and Finniss River and Lakes Alexandrina and Albert. Report to Department for Environment and Natural Resources. The South Australian Murray Darling Basin Natural Resources Management Board, Murray Bridge. South Australia.

- ^ Gehrig S, Nicol J & Marsland, K (2011) Lower Lakes Vegetation Condition Monitoring – 2010/2011. SARDI Aquatic Sciences, Adelaide.

- ^ Marsland, K & Nicol, J (2009) Lower Lakes vegetation condition monitoring 2008/09. SARDI Aquatic Sciences, Adelaide.

- ^ Wedderburn, S & Hillyard, K (2010) Condition monitoring of threatened fish populations at Lake Alexandrina and Lake Albert (2009-2010). The University of Adelaide, Adelaide.

- ^ Bice, C (2009) Literature review of the ecology of fishes of the Lower Murray, Lower Lakes and Coorong. Report the South Australian Department for Environment and Heritage. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide.

- ^ Berndt, Berndt & Stanton 1993, p. xvii.

- ^ Kartinyeri, Doreen (2006). Ngarriindjeri nation : genealogies of Ngarrindjeri families. Kent Town, South Australia: Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-725-4. OCLC 174134225.

- ^ Pate 2006, p. 226.

- ^ Clarke, Philip A. (2 January 2018). "Aboriginal foraging practices and crafts involving birds in the post-European period of the Lower Murray, South Australia". Transactions of the Royal Society of South Australia. 142 (1): 1–26. Bibcode:2018TRSAu.142....1C. doi:10.1080/03721426.2017.1415588. ISSN 0372-1426. S2CID 90685399.

- ^ Bell, Diane; Janet Mackenzie (2014). Ngarrindjeri wurruwarrin: a world that is, was, and will be (New ed.). North Melbourne, Australia. ISBN 978-1-74219-913-9. OCLC 882261142.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Bell, Dianne (1998). Ngarrindjeri Wurruwarrin: A world that is, was, and will be. Spinifex Press.

- ^ Mosley, Luke; Ye, Qifeng; Shepherd, Scoresby; Hemming, Steve; Fitzpatrick, Rob, eds. (1 December 2018). Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth region (Yarluwar-Ruwe). Royal Society of South Australia. doi:10.20851/natural-history-cllmm. hdl:2440/118010. ISBN 9781925261813. S2CID 239559925.

- ^ a b Hemming, Steve (1 December 2018), "Ngarrindjeri Nation Yarluwar-Ruwe Plan: Caring for Ngarrindjeri Country and Culture Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan (Listen to Ngarrindjeri People Talking)", Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth region (Yarluwar-Ruwe). Royal Society of South Australia, University of Adelaide Press, doi:10.20851/natural-history-cllmm-1.1, ISBN 9781925261813, S2CID 188908276

- ^ Rigney, Daryle; Hemming, Steve; Bignall, Simone; Maher, Katie (2018), "Ngarrindjeri Yannarumi: Educating for Transformation and Indigenous Nation (Re)building", Handbook of Indigenous Education, Singapore: Springer Singapore, pp. 1–26, doi:10.1007/978-981-10-1839-8_22-1, ISBN 978-981-10-1839-8, retrieved 23 November 2021

- ^ Hemming, Steve; Rigney, Daryle; Bignall, Simone; Berg, Shaun; Rigney, Grant (3 July 2019). "Indigenous nation building for environmental futures: Murrundi flows through Ngarrindjeri country". Australasian Journal of Environmental Management. 26 (3): 216–235. doi:10.1080/14486563.2019.1651227. ISSN 1448-6563. S2CID 203500578.

- ^ "The Kungun Ngarrindjeri Yunnan Agreement" (PDF). Department for Environment and Water. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2016.

- ^ "Ngarrindjeri and Commonwealth partner on environmental water". ABC News. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Native Title Determination Details". nntt.gov.au. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Cumpston, J. H. L. (1951). Charles Sturt, his life and journeys of exploration. Georgian House. OCLC 10264205.

- ^ Simons 2003, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Jeffery, Bill (August 1992). "Cultural contact along the Coorong in South Australia". Journal of the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology. 25: 29–38. ISSN 1057-2414.

- ^ Sturt, Charles (1833). Two expeditions into the interior of Southern Australia, during the years 1828, 1829, 1830, and 1831: with observations on the soil, climate, and general resources of the colony of New South Wales. London: Smith, Elder and Co. pp. 219, 271. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2021. 2 vols

- ^ "The Big Yabby, Australia Tourist Information". touristlink.com. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "SA Memory". samemory.sa.gov.au. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ a b Marino, Brad Collis, Melissa. "The Pioneers". stories.coretext.com.au. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Mosley, LM; Zammit, B; Leyden, E; Heneker, TM; Hipsey, MR; Skinner, D; Aldridge, KT (2012). "The Impact of Extreme Low Flows on the Water Quality of the Lower Murray River and Lakes (South Australia)". Water Resources Management. 26 (13): 3923–3946. doi:10.1007/s11269-012-0113-2. hdl:11343/282625. S2CID 154772804.

- ^ Mosley LM, Palmer D, Leyden E, Fitzpatrick R, and Shand P (2014). Changes in acidity and metal geochemistry in soils, groundwater, drain and river water in the Lower Murray after a severe drought. Science of the Total Environment 485–486: 281–291.

- ^ Mosley, LM; Zammit, B; Jolley, A; Barnett, L (2014). "Acidification of lake water due to drought". Journal of Hydrology. 511: 484–493. Bibcode:2014JHyd..511..484M. doi:10.1016/j.jhydrol.2014.02.001.

- ^ Mosley, LM; Palmer, D; Leyden, E; Fitzpatrick, R; Shand, P (2014). "Acidification of floodplains due to river level decline during drought". Journal of Contaminant Hydrology. 161: 10–23. Bibcode:2014JCHyd.161...10M. doi:10.1016/j.jconhyd.2014.03.003. PMID 24732706.

- ^ Hipsey, M; Salmon, U; Mosley, LM (2014). "A three-dimensional hydro-geochemical model to assess lake acidification risk". Environmental Modelling and Software. 61: 433–457. doi:10.1016/j.envsoft.2014.02.007.

- ^ Mosley, LM; Zammit, B; Jolley, A; Barnett, L; Fitzpatrick, R (2014). "Monitoring and assessment of surface water acidification following rewetting of oxidised acid sulfate soils". Environmental Monitoring and Assessment. 186 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1007/s10661-013-3350-9. PMID 23900634. S2CID 46559400.

- ^ Mosley, LM; Shand, P; Self, P; Fitzpatrick, R (2014). "The geochemistry during management of lake acidification caused by the rewetting of sulfuric (pH<4) acid sulfate soils". Applied Geochemistry. 41: 49–56. Bibcode:2014ApGC...41...49M. doi:10.1016/j.apgeochem.2013.11.010.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2009". bom.gov.au. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "The drought remembered, five years on | Photos". The Times. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Rob W.; Shand, P.; Mosley, Luke M. (1 December 2018), Mosley, Luke; Ye, Qifeng; Shepherd, Scoresby; Hemming, Steve (eds.), "Soils in the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth Region", Natural History of the Coorong, Lower Lakes, and Murray Mouth region (Yarluwar-Ruwe). Royal Society of South Australia, University of Adelaide Press, doi:10.20851/natural-history-cllmm-2.9, ISBN 978-1-925261-81-3, S2CID 134665471, retrieved 19 November 2021

- ^ "Money found for Murray flow restrictor's removal". ABC News. 3 August 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ "Jones' Lookout Mosaic – Michael Tye". Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ ANZECC (2000) Australian Water Quality Guidelines for Fresh and Marine Waters. Australian and New Zealand Environment and Conservation Council, Kingston.

- ^ https://www.awe.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/cewh-statement-carp_0.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ^ Stuart, I. G., & Jones, M. J. (2006). Movement of common carp, Cyprinus carpio, in a regulated lowland Australian river: implications for management. Fisheries Management and Ecology, 13(4), 213-219.

- ^ Kopf, R. K., Boutier, M., Finlayson, C. M., Hodges, K., Humphries, P., King, A., ... & Vanderplasschen, A. (2019). Biocontrol in Australia: Can a carp herpesvirus (CyHV-3) deliver safe and effective ecological restoration?. Biological Invasions, 21(6), 1857-1870.

- ^ Lighten, J. and van Oosterhout, C., 2017. Biocontrol of common carp in Australia poses risks to biosecurity. Nature ecology & evolution, 1(3), pp.1-1.

- ^ "The Carp Problem". carp.gov.au.

- ^ Gailberger, Jade (30 December 2016). "Fishers fear release of herpes virus to kill River Murray's European carp will devastate the industry".

- ^ "River Murray Turtles need your help!". GWLAP. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Help The Kids Help The Turtles in SA Lakes And Lower Murray – Pigs Will Fly". pigswillfly.com.au. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Grant Award View – GA21295: GrantConnect". grants.gov.au. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Turtles win in River Murray crisis". ABC News. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ "Clayton Bay Foreshore Walk". weekendnotes.com. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Van Dyke, J. U.; Spencer, R. –J.; Thompson, M. B.; Chessman, B.; Howard, K.; Georges, A. (December 2019). "Conservation implications of turtle declines in Australia's Murray River system". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 1998. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.1998V. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-39096-3. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6374471. PMID 30760813.

- ^ Council, Alexandrina (11 September 2019). "Dogs and Cats". Alexandrina Council WEBSITE PAGES. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Whiterod, Nick (19 March 2020). "The frogtastic Southern Bell Frog facility – Nature Glenelg Trust". Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (2014). Frog Monitoring in the Coorong, Lower Lakes and Murray Mouth (CLLMM) Region. Adelaide: Government of South Australia.

- ^ Whiterod, Nick (19 December 2019). "Our Southern Bell Frog conservation facility is go...with tadpoles! – Nature Glenelg Trust". Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- ^ Manning, Jack (7 November 2019). "Streets are dark as lights remain switched off following tampering and gunshot damage". The Times. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ^ "Trove". trove.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Vale Annabelle Collett". The Times. 15 April 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Neylon, John (30 March 2020). "The colourful, subversive world of Annabelle Collett". The Adelaide Review. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Dr. Deane Fergie". LocuSAR. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ perkinsy (13 October 2013). "Review: My Ngarrindjeri Calling". Stumbling Through the Past. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Caggiano, Anthony (16 April 2014). "Henry Jones' legacy to live on". The Times. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Dr. Rod Lucas". LocuSAR. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

Sources

- Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen; Stanton, John E. (1993). A World that was: The Yaraldi of the Murray River and the Lakes, South Australia. University of British Columbia UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-774-80478-3.

- Pate, F Donald (2006). "Hunter-gatherer social complexity at Roonka Flat, South Australia" (PDF). In Bruno, David; Barker, Bryce; McNiven, Ian J (eds.). Social Archaeology of Australian Indigenous Societies. Aboriginal Studies Press. pp. 226–241.

- Simons, M. (2003). The Meeting of the Waters: The Hindmarsh Island Affair. Sydney: Hodder Headline. ISBN 0-7336-1348-9.