Arthur Compton

Arthur Compton | |

|---|---|

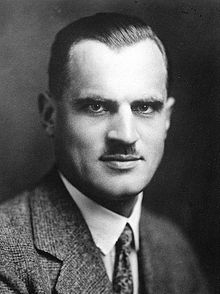

Compton in 1927 | |

| Born | Arthur Holly Compton September 10, 1892 Wooster, Ohio, U.S. |

| Died | March 15, 1962 (aged 69) Berkeley, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse |

Betty Charity McCloskey

(m. 1916) |

| Children | 2, including John Joseph |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Hereward L. Cooke |

| Doctoral students | |

| Signature | |

Arthur Holly Compton (September 10, 1892 – March 15, 1962) was an American physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927 for his 1923 discovery of the Compton effect, which demonstrated the particle nature of electromagnetic radiation. It was a sensational discovery at the time: the wave nature of light had been well-demonstrated, but the idea that light had both wave and particle properties was not easily accepted. He is also known for his leadership over the Metallurgical Laboratory at the University of Chicago during the Manhattan Project, and served as chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis from 1945 to 1953.

In 1919, Compton was awarded one of the first two National Research Council Fellowships that allowed students to study abroad. He chose to go to the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory in England, where he studied the scattering and absorption of gamma rays. Further research along these lines led to the discovery of the Compton effect. He used X-rays to investigate ferromagnetism, concluding that it was a result of the alignment of electron spins, and studied cosmic rays, discovering that they were made up principally of positively charged particles.

During World War II, Compton was a key figure in the Manhattan Project that developed the first nuclear weapons. His reports were important in launching the project. In 1942, he became head of the Metallurgical Laboratory, with responsibility for producing nuclear reactors to convert uranium into plutonium, finding ways to separate the plutonium from the uranium and to design an atomic bomb. Compton oversaw Enrico Fermi's creation of Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor, which went critical on December 2, 1942. The Metallurgical Laboratory was also responsible for the design and operation of the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Plutonium began being produced in the Hanford Site reactors in 1945.

After the war, Compton became chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis. During his tenure, the university formally desegregated its undergraduate divisions, named its first female full professor, and enrolled a record number of students after wartime veterans returned to the United States.

Early life

Arthur Compton was born on September 10, 1892, in Wooster, Ohio, the son of Elias and Otelia Catherine (née Augspurger) Compton,[1] who was named American Mother of the Year in 1939.[2] They were an academic family. Elias was dean of the University of Wooster (later the College of Wooster), which Arthur also attended. Arthur's eldest brother, Karl, who also attended Wooster, earned a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) degree in physics from Princeton University in 1912, and was president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1930 to 1948. His second brother Wilson likewise attended Wooster, earned his PhD in economics from Princeton in 1916 and was president of the State College of Washington, later Washington State University from 1944 to 1951.[3] All three brothers were members of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity.[4]

Compton was initially interested in astronomy, and took a photograph of Halley's Comet in 1910.[5] Around 1913, he described an experiment where an examination of the motion of water in a circular tube demonstrated the rotation of the earth, a device now known as the Compton generator.[6] That year, he graduated from Wooster with a Bachelor of Science degree and entered Princeton, where he received his Master of Arts degree in 1914.[7] Compton then studied for his PhD in physics under the supervision of Hereward L. Cooke, writing his dissertation on The Intensity of X-Ray Reflection, and the Distribution of the Electrons in Atoms.[8]

When Arthur Compton earned his PhD in 1916, he, Karl and Wilson became the first group of three brothers to earn Ph.D.s from Princeton. Later, they would become the first such trio to simultaneously head American colleges.[3] Their sister Mary married a missionary, C. Herbert Rice, who became the principal of Forman Christian College in Lahore.[9] In June 1916, Compton married Betty Charity McCloskey, a Wooster classmate and fellow graduate.[9] They had two sons, Arthur Alan Compton and John Joseph Compton.[10]

Compton spent a year as a physics instructor at the University of Minnesota in 1916–17,[11] then two years as a research engineer with the Westinghouse Lamp Company in Pittsburgh, where he worked on the development of the sodium-vapor lamp. During World War I he developed aircraft instrumentation for the Signal Corps.[9]

In 1919, Compton was awarded one of the first two National Research Council Fellowships that allowed students to study abroad. He chose to go to the University of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory in England. Working with George Paget Thomson, the son of J. J. Thomson, Compton studied the scattering and absorption of gamma rays. He observed that the scattered rays were more easily absorbed than the original source.[11][12] Compton was greatly impressed by the Cavendish scientists, especially Ernest Rutherford, Charles Galton Darwin and Arthur Eddington, and he ultimately named his second son after J. J. Thomson.[12]

From 1926–1927, he taught at the department of chemistry of the University of the Punjab where he was a Guggenheim Fellow.[13][14]

For a time Compton was a deacon at a Baptist church. "Science can have no quarrel", he said, "with a religion which postulates a God to whom men are as His children."[15]

Career

Compton effect

Returning to the United States, Compton was appointed Wayman Crow Professor of Physics, and head of the department of physics at Washington University in St. Louis in 1920.[7] In 1922, he found that X-ray quanta scattered by free electrons had longer wavelengths and, in accordance with Planck's relation, less energy than the incoming X-rays, the surplus energy having been transferred to the electrons. This discovery, known as the "Compton effect" or "Compton scattering", demonstrated the particle concept of electromagnetic radiation.[16][17]

In 1923, Compton published a paper in the Physical Review that explained the X-ray shift by attributing particle-like momentum to photons, something Einstein had invoked for his 1905 Nobel Prize–winning explanation of the photo-electric effect. First postulated by Max Planck in 1900, these were conceptualized as elements of light "quantized" by containing a specific amount of energy depending only on the frequency of the light.[18] In his paper, Compton derived the mathematical relationship between the shift in wavelength and the scattering angle of the X-rays by assuming that each scattered X-ray photon interacted with only one electron. His paper concludes by reporting on experiments that verified his derived relation:

where

- is the initial wavelength,

- is the wavelength after scattering,

- is the Planck constant,

- is the electron rest mass,

- is the speed of light, and

- is the scattering angle.[17]

The quantity h⁄mec is known as the Compton wavelength of the electron; it is equal to 2.43×10−12 m. The wavelength shift λ′ − λ lies between zero (for θ = 0°) and twice the Compton wavelength of the electron (for θ = 180°).[19] He found that some X-rays experienced no wavelength shift despite being scattered through large angles; in each of these cases the photon failed to eject an electron. Thus the magnitude of the shift is related not to the Compton wavelength of the electron, but to the Compton wavelength of the entire atom, which can be upwards of 10,000 times smaller.[17]

"When I presented my results at a meeting of the American Physical Society in 1923", Compton later recalled, "it initiated the most hotly contested scientific controversy that I have ever known."[20] The wave nature of light had been well demonstrated, and the idea that it could have a dual nature was not easily accepted. It was particularly telling that diffraction in a crystal lattice could only be explained with reference to its wave nature. It earned Compton the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1927. Compton and Alfred W. Simon developed the method for observing at the same instant individual scattered X-ray photons and the recoil electrons. In Germany, Walther Bothe and Hans Geiger independently developed a similar method.[16]

X-rays

In 1923, Compton moved to the University of Chicago as professor of physics,[7] a position he would occupy for the next 22 years.[16] In 1925, he demonstrated that the scattering of 130,000-volt X-rays from the first sixteen elements in the periodic table (hydrogen through sulfur) were polarized, a result predicted by J. J. Thomson. William Duane from Harvard University spearheaded an effort to prove that Compton's interpretation of the Compton effect was wrong. Duane carried out a series of experiments to disprove Compton, but instead found evidence that Compton was correct. In 1924, Duane conceded that this was the case.[16]

Compton investigated the effect of X-rays on the sodium and chlorine nuclei in salt. He used X-rays to investigate ferromagnetism, concluding that it was a result of the alignment of electron spins.[21] In 1926, he became a consultant for the Lamp Department at General Electric. In 1934, he returned to England as Eastman visiting professor at Oxford University. While there, General Electric asked him to report on activities at General Electric Company plc's research laboratory at Wembley. Compton was intrigued by the possibilities of the research there into fluorescent lamps. His report prompted a research program in America that developed it.[22][23]

Compton's first book, X-Rays and Electrons, was published in 1926. In it he showed how to calculate the densities of diffracting materials from their X-ray diffraction patterns.[21] He revised his book with the help of Samuel K. Allison to produce X-Rays in Theory and Experiment (1935). This work remained a standard reference for the next three decades.[24]

Cosmic rays

By the early 1930s, Compton had become interested in cosmic rays. At the time, their existence was known but their origin and nature remained speculative. Their presence could be detected using a spherical "bomb" containing compressed air or argon gas and measuring its electrical conductivity. Trips to Europe, India, Mexico, Peru and Australia gave Compton the opportunity to measure cosmic rays at different altitudes and latitudes. Along with other groups who made observations around the globe, they found that cosmic rays were 15% more intense at the poles than at the equator. Compton attributed this to the effect of cosmic rays being made up principally of charged particles, rather than photons as Robert Millikan had suggested, with the latitude effect being due to Earth's magnetic field.[25]

Manhattan Project

In April 1941, Vannevar Bush, head of the wartime National Defense Research Committee (NDRC), created a special committee headed by Compton to report on the NDRC uranium program. Compton's report, which was submitted in May 1941, foresaw the prospects of developing radiological weapons, nuclear propulsion for ships, and nuclear weapons using uranium-235 or the recently discovered plutonium.[26] In October he wrote another report on the practicality of an atomic bomb. For this report, he worked with Enrico Fermi on calculations of the critical mass of uranium-235, conservatively estimating it to be between 20 kilograms (44 lb) and 2 tonnes (2.0 long tons; 2.2 short tons). He also discussed the prospects for uranium enrichment with Harold Urey, spoke with Eugene Wigner about how plutonium might be produced in a nuclear reactor, and with Robert Serber about how the plutonium produced in a reactor might be separated from uranium. His report, submitted in November, stated that a bomb was feasible, although he was more conservative about its destructive power than Mark Oliphant and his British colleagues.[27]

The final draft of Compton's November report made no mention of using plutonium, but after discussing the latest research with Ernest Lawrence, Compton became convinced that a plutonium bomb was also feasible. In December, Compton was placed in charge of the plutonium project.[28] He hoped to achieve a controlled chain reaction by January 1943, and to have a bomb by January 1945. To tackle the problem, he had the research groups working on plutonium and nuclear reactor design at Columbia University, Princeton University and the University of California, Berkeley, concentrated together as the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago. Its objectives were to produce reactors to convert uranium to plutonium, to find ways to chemically separate the plutonium from the uranium, and to design and build an atomic bomb.[29]

In June 1942, the United States Army Corps of Engineers assumed control of the nuclear weapons program and Compton's Metallurgical Laboratory became part of the Manhattan Project.[30] That month, Compton gave Robert Oppenheimer responsibility for bomb design.[31] It fell to Compton to decide which of the different types of reactor designs that the Metallurgical Laboratory scientists had devised should be pursued, even though a successful reactor had not yet been built.[32]

When labor disputes delayed construction of the Metallurgical Laboratory's new home in the Argonne Forest preserve, Compton decided to build Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor, under the stands at Stagg Field.[33] Under Fermi's direction, it went critical on December 2, 1942.[34] Compton arranged for Mallinckrodt to undertake the purification of uranium ore,[35] and with DuPont to build the plutonium semi-works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[36]

A major crisis for the plutonium program occurred in July 1943, when Emilio Segrè's group confirmed that plutonium created in the X-10 Graphite Reactor at Oak Ridge contained high levels of plutonium-240. Its spontaneous fission ruled out the use of plutonium in a gun-type nuclear weapon. Oppenheimer's Los Alamos Laboratory met the challenge by designing and building an implosion-type nuclear weapon.[27]

Compton was at the Hanford site in September 1944 to watch the first reactor being brought online. The first batch of uranium slugs was fed into Reactor B at Hanford in November 1944, and shipments of plutonium to Los Alamos began in February 1945.[37] Throughout the war, Compton would remain a prominent scientific adviser and administrator. In 1945, he served, along with Lawrence, Oppenheimer, and Fermi, on the Scientific Panel that recommended military use of the atomic bomb against Japan.[38] He was awarded the Medal for Merit for his services to the Manhattan Project.[39]

Return to Washington University

After the war ended, Compton resigned his chair as Charles H. Swift Distinguished Service Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago and returned to Washington University in St. Louis, where he was inaugurated as the university's ninth chancellor in 1946.[39] During Compton's time as chancellor, the university formally desegregated its undergraduate divisions in 1952, named its first female full professor, and enrolled record numbers of students as wartime veterans returned to the United States. His reputation and connections in national scientific circles allowed him to recruit many nationally renowned scientific researchers to the university. Despite Compton's accomplishments, he was criticized then, and subsequently by historians, for moving too slowly toward full racial integration, making Washington University the last major institution of higher learning in St. Louis to open its doors to African Americans.[40]

Compton retired as chancellor in 1954, but remained on the faculty as Distinguished Service Professor of Natural Philosophy until his retirement from the full-time faculty in 1961. In retirement he wrote Atomic Quest, a personal account of his role in the Manhattan Project, which was published in 1956.[39]

Philosophy

Compton was one of a handful of scientists and philosophers to propose a two-stage model of free will. Others include William James, Henri Poincaré, Karl Popper, Henry Margenau, and Daniel Dennett.[41] In 1931, Compton championed the idea of human freedom based on quantum indeterminacy, and invented the notion of amplification of microscopic quantum events to bring chance into the macroscopic world. In his somewhat bizarre mechanism, he imagined sticks of dynamite attached to his amplifier, anticipating the Schrödinger's cat paradox, which was published in 1935.[42]

Reacting to criticisms that his ideas made chance the direct cause of people's actions, Compton clarified the two-stage nature of his idea in an Atlantic Monthly article in 1955. First there is a range of random possible events, then one adds a determining factor in the act of choice.[43]

A set of known physical conditions is not adequate to specify precisely what a forthcoming event will be. These conditions, insofar as they can be known, define instead a range of possible events from among which some particular event will occur. When one exercises freedom, by his act of choice he is himself adding a factor not supplied by the physical conditions and is thus himself determining what will occur. That he does so is known only to the person himself. From the outside one can see in his act only the working of physical law. It is the inner knowledge that he is in fact doing what he intends to do that tells the actor himself that he is free.[43]

Religious views

Compton was a Presbyterian.[44] His father Elias was an ordained Presbyterian minister.[44]

Compton lectured on a "Man's Place in God's World" at Yale University, Western Theological Seminary and the University of Michigan in 1934–35.[44] The lectures formed the basis of his book The Freedom of Man. His chapter "Death, or Life Eternal?" argued for Christian immortality and quoted verses from the Bible.[44][45] From 1948 to 1962, Compton was an elder of the Second Presbyterian Church in St. Louis.[44] In his later years, he co-authored the book Man's Destiny in Eternity. Compton set Jesus as the center of his faith in God's eternal plan.[44] He once commented that he could see Jesus' spirit at work in the world as an aspect of God alive in men and women.[44]

Death and legacy

Compton died in Berkeley, California, from a cerebral hemorrhage on March 15, 1962. He was outlived by his wife (who died in 1980) and sons. Compton is buried in the Wooster Cemetery in Wooster, Ohio.[10] Before his death, he was professor-at-large at the University of California, Berkeley for spring 1962.[46]

Compton received many awards in his lifetime, including the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1927, the Matteucci Gold Medal in 1930, the Royal Society's Hughes Medal and the Franklin Institute's Franklin Medal in 1940.[47] He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1925,[48] the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1927,[49] and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1928.[50] He is commemorated in various ways. Compton crater on the Moon is co-named for Compton and his brother Karl.[51] The physics research building at Washington University in St Louis is named in his honor,[52] as is the university's top fellowship for undergraduate students studying math, physics, or planetary science.[53] Compton invented a more gentle, elongated, and ramped version of the speed bump called the "Holly hump", many of which are on the roads of the Washington University campus.[54] The University of Chicago remembered Compton and his achievements by dedicating the Arthur H. Compton House in his honor.[55] It is now listed as a National Historic Landmark.[56] Compton also has a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.[57] NASA's Compton Gamma Ray Observatory was named in honor of Compton. The Compton effect is central to the gamma ray detection instruments aboard the observatory.[58]

Bibliography

- Compton, Arthur (1926). X-Rays and Electrons: An Outline of Recent X-Ray Theory. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. OCLC 1871779.

- Compton, Arthur; with Allison, S. K. (1935). X-Rays in Theory and Experiment. New York: D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. OCLC 853654.

- Compton, Arthur (1935). The Freedom of Man. New Haven: Yale University Press. OCLC 5723621.

- Compton, Arthur (1940). The Human Meaning of Science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. OCLC 311688.

- Compton, Arthur (1949). Man's Destiny in Eternity. Boston: Beacon Press. OCLC 4739240.

- Compton, Arthur (1956). Atomic Quest. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 173307.

- Compton, Arthur (1967). Johnston, Marjorie (ed.). The Cosmos of Arthur Holly Compton. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 953130.

- Compton, Arthur (1973). Shankland, Robert S. (ed.). Scientific Papers of Arthur Holly Compton. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-11430-9. OCLC 962635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Notes

- ^ Hockey 2007, p. 244.

- ^ "Past National Mothers of the Year". American Mothers, Inc. Archived from the original on March 23, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ a b Compton 1967, p. 425.

- ^ "The Official History of the Beta Beta Chapter of the Alpha Tau Omega Fraternity". Alpha Tau Fraternity. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Compton 1967, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Compton, A. H. (May 23, 1913). "A Laboratory Method of Demonstrating the Earth's Rotation". Science. 37 (960): 803–06. Bibcode:1913Sci....37..803C. doi:10.1126/science.37.960.803. PMID 17838837.

- ^ a b c "Arthur H. Compton – Biography". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Arthur Holly Compton (1892–1962)" (PDF). University of Notre Dame. Retrieved July 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c Allison 1965, p. 82.

- ^ a b Allison 1965, p. 94.

- ^ a b Allison 1965, p. 83.

- ^ a b Compton 1967, p. 27.

- ^ "University of the Punjab – Science". pu.edu.pk. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ Newspaper, From the (October 15, 2014). "Nobel Laureates from Lahore". DAWN.COM. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- ^ "Science: Cosmic Clearance". Time. January 13, 1936. Archived from the original on October 24, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Allison 1965, pp. 84–86.

- ^ a b c Compton, Arthur H. (May 1923). "A Quantum Theory of the Scattering of X-Rays by Light Elements". Physical Review. 21 (5): 483–502. Bibcode:1923PhRv...21..483C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.21.483.

- ^ Gamow 1966, pp. 17–23.

- ^ "The Compton wavelength of the electron". University of California Riverside. Archived from the original on November 10, 1996. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ^ Compton 1967, p. 36.

- ^ a b Allison 1965, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Allison 1965, pp. 88–89.

- ^ "Eastman Professorship". The Association of American Rhodes Scholars. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ Allison 1965, p. 90.

- ^ Compton 1967, pp. 157–163.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 36–38.

- ^ a b Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 103.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, p. 174.

- ^ Allison 1965, p. 92.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Hewlett & Anderson 1962, pp. 304–310.

- ^ "Recommendations on the Immediate Use of Nuclear Weapons". nuclearfiles.org. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ a b c Allison 1965, p. 93.

- ^ Pfeiffenberger, Amy M. (Winter 1989). "Democracy at Home: The Struggle to Desegregate Washington University in the Postwar Era". Gateway-Heritage. 10 (3). Missouri Historical Society: 17–24.

- ^ "Two-Stage Models for Free Will". The Information Philosopher. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ Compton, A. H. (August 14, 1931). "The Uncertainty Principle and Free Will". Science. 74 (1911): 172. Bibcode:1931Sci....74..172C. doi:10.1126/science.74.1911.172. PMID 17808216. S2CID 29126625.

- ^ a b Compton 1967, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f g Blackwood, James R. (1988). "Arthur Compton's Atomic Venture". American Presbyterians. 66 (3): 177–193. JSTOR 23330520.

- ^ Eikner, Allen V. (1980). Religious Perspectives and Problems An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. University Press of America. pp. 194–203. ISBN 978-0-8191-1215-6

- ^ "Arthur Holly Compton: Systemwide". California Digital Library. Retrieved May 24, 2017.

- ^ Allison 1965, p. 97.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Arthur H. Compton". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Arthur Holly Compton". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. February 9, 2023. Retrieved August 14, 2023.

- ^ "Compton". Tangient LLC. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Arthur Holly Compton Laboratory of Physics". Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Honorary Scholars Program in Arts and Sciences". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on February 15, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

- ^ "Compton Speed Bumps for Traffic Control, 1953". Washington University in St. Louis. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Compton House". University of Chicago. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ "Compton, Arthur H., House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 12, 2012. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- ^ St. Louis Walk of Fame. "St. Louis Walk of Fame Inductees". stlouiswalkoffame.org. Archived from the original on October 31, 2012. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ^ "The CGRO Mission (1991–2000)". NASA. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

References

- Allison, Samuel K. (1965). "Arthur Holly Compton 1892–1962". Biographical Memoirs. 38. National Academy of Sciences: 81–110. ISSN 0077-2933. OCLC 1759017.

- Gamow, George (1966). Thirty Years That Shook Physics: The Story of Quantum Theory. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-486-24895-X. OCLC 11970045.

- Hewlett, Richard G.; Anderson, Oscar E. (1962). The New World, 1939–1946 (PDF). University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-520-07186-7. OCLC 637004643. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Hockey, Thomas (2007). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. OCLC 263669996. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

Further reading

- Bernstein, Barton J. (1988). "Four Physicists and the Bomb: The Early Years, 1945–1950". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 18 (2): 231–263. doi:10.2307/27757603. JSTOR 27757603.; covers Oppenheimer, Fermi, Lawrence and Compton.

- Galison, Peter; Bernstein, Barton J. (1989). "In any light: Scientists and the decision to build the Superbomb, 1952–1954". Historical Studies in the Physical and Biological Sciences. 19 (2): 267–347. doi:10.2307/27757627. JSTOR 27757627.

External links

Media related to Arthur Compton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Arthur Compton at Wikimedia Commons

- "Strange Instrument Built to Solve Mystery of Cosmic Rays", April 1932, Popular Science article about Compton on research on cosmic rays

- Arthur Compton biographical entry at Washington University in St. Louis

- Annotated bibliography for Arthur Compton from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Arthur Holly Compton on Information Philosopher

- Arthur Compton on Nobelprize.org

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- Arthur Compton at Find a Grave

- Guide to the Arthur Holly Compton Papers 1918–1964 at the University of Chicago Special Collections Research Center

- 1892 births

- 1962 deaths

- American Nobel laureates

- American Presbyterians

- Chancellors of Washington University in St. Louis

- College of Wooster alumni

- Manhattan Project people

- Nobel laureates in Physics

- Particle physicists

- People from Wooster, Ohio

- Princeton University alumni

- Quantum physicists

- Optical physicists

- Fellows of the American Association for the Advancement of Science

- Recipients of the Pour le Mérite (civil class)

- College of Wooster

- Washington University in St. Louis faculty

- Scientists from Missouri

- Physicists from Missouri

- Theoretical physicists

- Spectroscopists

- Naval Consulting Board

- 20th-century American physicists

- Washington University physicists

- Nobel laureates affiliated with Missouri

- Recipients of the Matteucci Medal

- Writers about religion and science

- University of Chicago faculty

- University of Minnesota faculty

- Presidents of the American Physical Society

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Recipients of Franklin Medal