Serbian Empire

The Serbian Empire (Template:Lang-sr, pronounced [sr̩̂pskoː tsâːrstʋo]) was a medieval Serbian state that emerged from the Kingdom of Serbia. It was established in 1346 by Dušan the Mighty, who significantly expanded the state.

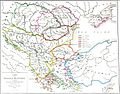

During Dušan's rule, Serbia was the most powerful state in Southeast Europe and one of the most powerful European states.[1] It was an Eastern Orthodox multi-ethnic and multi-lingual empire that stretched from the Danube in the north to the Gulf of Corinth in the south, with its capital in Skopje.[2] He also promoted the Serbian Archbishopric to the Serbian Patriarchate. His son and successor, Uroš the Weak, lost most of the territory conquered by Dušan, hence his epithet.

The Serbian Empire effectively ended with the death of Uroš V in 1371 and the break-up of the Serbian state. Some successors of Stefan V claimed the title of Emperor in parts of Serbia until 1402, but the territory in Greece was never recovered.[3][4][5]

History

Establishment

Stefan Dušan was the son of the Serbian king Stefan Dečanski (r. 1322–1331). After his father's accession to the throne, Dušan was awarded with the title of "young king". Although this title bore significant power in medieval Serbia, Stefan wanted his younger son, Simeon Uroš, to inherit him instead of Dušan. However, Dušan had significant support from the major part of the Serbian nobility, including the Serbian archbishop Danilo, and some of the king's most trusted generals, such as Jovan Oliver Grčinić. Tensions slowly rose between the king and his son, especially after the battle of Velbužd, where Dušan showed his military capabilities, and they seem to have culminated when king Stefan raided Zeta, a province in Serbia where Dušan ruled autonomously, being a tradition of Serbian heirs to rule this province. Advised by the nobility, Dušan later marched from Zeta to Nerodimlje, where he besieged his father and forced him to surrender the throne. Stefan was later imprisoned in the fortress of Zvečan, where he died.

In 1333, Dušan launched a large attack on the Byzantine empire, at the time ruled by the ambitious emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, with the help of a deserted Byzantine general, Syrgian. Dušan quickly conquered the cities of Ohrid, Prilep and Kastoria, and attempted to besiege Thessalonica in 1334, but was prevented conquering the city by the death of Syrgian, who had been assassinated by a Byzantine spy. Syrgian was a key figure in Dušan's army, as he had earned a great reputation in Greece, convincing Greek citizens to surrender cities rather than fight Dušan's armies.

By 1345, Dušan the Mighty had expanded his state to cover half of the Balkans, more territory than either the Byzantine Empire or the Second Bulgarian Empire in that time. Therefore, in 1345, in Serres, Dušan proclaimed himself "Tsar" ("Caesar").[6] On 16 April 1346, in Skopje (former Bulgarian capital), he had himself crowned "Emperor of the Serbs and Greeks", a title signifying a claim to succession of the Byzantine Empire. The ceremony was performed by the newly elevated Serbian Patriarch Joanikije II, the Bulgarian Patriarch Simeon, and Nicholas, the Archbishop of Ohrid. At the same time, Dušan had his son Uroš crowned as King of Serbs and Greeks, giving him nominal rule over the Serbian lands, although Dušan was governing the whole state, with special responsibility for the newly acquired Roman (Byzantine) lands. These actions, which the Byzantines received with indignation, appear to have been supported by the Bulgarian Empire and tsar Ivan Alexander, as the Patriarch of Bulgaria Simeon had participated in both the creation of a Serbian Patriarchate of Peć and the imperial coronation of Stefan Uroš IV Dušan.[7] Dushan made marriage alliance with Bulgarian tsar Ivan Alexander, marrying his sister Helena.[8][6]

Reign of Stefan Dušan

Tsar Dušan doubled the size of Serbian state, seizing territories in all directions, especially south and southeast. Serbia held parts of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moravian Serbia, Kosovo, Zeta, modern North Macedonia, modern Albania, and half of modern Greece. He did not fight a single field battle, instead winning his empire by besieging cities. Dušan undertook a campaign against the Byzantine Empire, which was attempting to avert a deteriorating situation after the destruction caused by the Fourth Crusade. Dušan swiftly seized Thessaly, Albania, Epirus, and most of Macedonia.

After besieging the emperor at Salonica in 1340, he imposed a treaty assuring Serbia sovereignty over regions extending from the Danube to the Gulf of Corinth, from the Adriatic Sea to the Maritsa river, and including parts of southern Bulgaria up to the environs of Adrianople. Bulgaria had never fully recovered since its defeat by the Serbs at the Battle of Velbazhd.[9] The outcome of the battle shaped the balance of power in the Balkans for the next decades to come and although Bulgaria did not lose territory, the Serbs could occupy much of Macedonia.[10] Bulgarian tsar Ivan Alexander, whose sister Helena Dušan later married, became his ally between 1332 and 1365.[11] Dušan ruled over major central part of the Balkan peninsula. He gave sanctuary to the former regent of the Byzantine Empire, John VI Kantakouzenos, in revolt against the government, and agreed to an alliance.

In 1349 and 1354, Dušan enacted a set of laws known as Dušan's Code. The Code was based on Roman-Byzantine law and the first Serbian constitution, St. Sava's Nomocanon (1219). It was a Civil and Canon law system, based on the Ecumenical Councils, for the functioning of the state and the Serbian Orthodox Church. In 1355, Dušan began military preparations for new campaigns in the south and east, but suddenly died of an unknown illness in December 1355.[12]

Expansion into Bosnia and Dalmatia

| History of Serbia |

|---|

|

|

|

Bordering Serbia to the west was the banate of Bosnia, ruled by Stephen II Kotromanic. During the reign of Dušan's father, Stefan Dečanski, Stephen expanded his rule to the Serbian provinces of Hum and Krajina, which stretched from Dubrovnik on the east to river Cetina on the west, Dušan, being busy with his conquests on the south, tried to solve this territorial dispute with diplomacy, but that did not succeed, as Stephen continually refused or ignored Dušan's requests, counting on the help of his Hungarian protector king Louis I.

However, the situation changed when Louis signed a treaty with Dušan, so he could attack the kingdom of Naples without Dušan attacking him from the south. Stephen, feeling that his position in Hum and Krajina is becoming harder to defend, started building fortresses around river Neretva, to strengthen his presence and even went as far as to raid the Serbian province of Travunia, reaching as far as Kotor. Dušan could not tolerate this, so he marched with his army westward.

Dušan led 50,000 infantry and 30,000 cavalry[citation needed] across the Bosnian border. Stephen, knowing he could not face such a force, opted to retreat in front of it in hopes of leading the Serbian army into hard terrain, where he could potentially fight them off. However, this did not work out because Bosnian nobility and even some of Stephen's own soldiers, unhappy with his rule, started defecting to Dušan. Dušan soon reached Bobovac, the capital of Bosnia, to which he laid siege. The Bosnian ban fled to Hungary, and Bosnia was left open for Dušan to conquer.

He left a portion of his army to continue besieging Bobovac; sent another portion to conquer the region of Krajina, while he himself led a third portion to conquer Hum. Then, after conquering Hum, Dušan proceeded to enter Dalmatia, in order to secure his sister's domains. His sister, Jelena Nemanjic-Subic, was married to the ban of Croatia, Mladen Subic, who died of plague in 1348, leaving his lands to his wife. After his death, Hungarians and Venetians both continually tried to take control over these lands, so Dušan entered Dalmatia to protect his sister's legal domains. He was welcomed as a liberator in Sibenik and Trogir, but as the Byzantine emperor John Kantakouzenos attacked Dušan from the south, capturing the city of Veria and Edessa, Dušan was forced to retreat and repel him. While he was on his way back, he was welcomed and prepared a great feast in Dubrovnik, where his wife stayed for some time.

It is unclear if Dušan kept control in these lands. Certain historians say Stephen Kotromanic returned and regained control in Bosnia, but the sources do not mention anything about him after Dušan's conquests, until his death in late 1353. Dušan most likely kept control over Dalmatia, since after his conquests, Serbian Orthodox monastery of Krka was built in that region. Also, he is recorded sending 2 military units under the command of his generals Đuraš Ilijić and Palman Bracht to protect the Dalmatian cities of Klis and Skradin in 1355. Djuras Ilijic surrendered Skradin to the Venetians some time after Dušan's death, on 10 January 1356, and Klis was conquered by the Croatian general Nikola Banic for the Hungarian king sometime after 1356, ending Serbian presence in Dalmatia.

Reign of Stefan Uroš V

Dušan was succeeded by his son, Stefan Uroš V, called "the Weak," a term that also described the empire as it slowly slid into feudal anarchy. The failure to consolidate its holdings after a sudden conquest led to the fragmentation of the empire. The period was marked by the rise of a new threat: the Ottoman Turkish sultanate gradually spread from Asia to Europe and conquered first Byzantine Thrace, and then the other Balkan states. Too incompetent to sustain the empire created by his father, Stefan V could neither repel attacks of foreign enemies nor combat the independence of his nobility. The Serbian Empire of Stefan V fragmented into a conglomeration of principalities, some of which did not even nominally acknowledge his rule. Stefan Uroš V died childless on 4 December 1371, after much of the Serbian nobility had been killed by the Ottoman Turks during the Battle of Maritsa.

Aftermath and legacy

The crumbling Serbian Empire under Uroš the Weak offered little resistance to the powerful Ottomans. In the wake of internal conflicts and decentralization of the state, the Ottomans defeated the Serbs under Vukašin at the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, making vassals of the southern governors; soon thereafter, the Emperor died.[13] As Uroš was childless and the nobility could not agree on a rightful heir, the Empire continued to be ruled by semi-independent provincial lords, who often were in feud with each other. The most powerful of these, Lazar Hrebeljanović, a Duke of present-day central Serbia (which had not yet come under Ottoman rule), stood against the Ottomans at the Battle of Kosovo in 1389. The result was indecisive, but it led to the subsequent fall of Serbia. Stefan Lazarević, the son of Lazar, succeeded as ruler, but by 1394 he had become an Ottoman vassal. In 1402 he renounced Ottoman rule and became a Hungarian ally; the following years are characterized by a power struggle between the Ottomans and Hungary over the territory of Serbia. In 1453, the Ottomans conquered Constantinople, and in 1458 Athens was taken. In 1459, Serbia was annexed, and then Morea a year later. During the following centuries of Ottoman rule, the legacy of former statehood, embodied in the Serbian Empire, became an integral part of Serbian national identity.[14]

Administration

Law

After finishing most of his conquests, Stefan Dušan dedicated himself to supervising the administration of the empire. One key objective was to create a written legal code, an effort his predecessors had only begun. An assembly of bishops, nobles, and provincial governors was charged with creating a code of laws, bringing together the customs of the Slav countries.

Dušan's Code was enacted in two state assemblies, the first on May 21, 1349, in Skopje, and the second in 1354 in Serres.[15][16] The law regulated all social spheres, thus it is considered a medieval constitution. The Code included 201 articles, based on Roman-Byzantine law. The legal transplanting is notable with the articles 172 and 174 of Dušan's Code, which regulated juridical independence. They were taken from the Byzantine code Basilika (book VII, 1, 16–17). The Code had its roots in the first Serbian constitution – St. Sava's Nomocanon (Template:Lang-sr) from 1219, enacted by Saint Sava. St. Sava's Nomocanon was the compilation of Civil law, based on Roman Law and Canon law, based on Ecumenical Councils. Its basic purpose was to organize the functions of the state and Serbian Orthodox Church.[17][18]

The legislation resembled the feudal system then prevalent in Western Europe, with an aristocratic basis and establishing a wide distinction between nobility and peasantry.[19] The monarch had broad powers but was surrounded and advised by a permanent council of magnates and prelates. The court, chancellery and administration were rough copies of those of Constantinople. The code enumerated the administrative hierarchy as following: "lands, cities, župas and krajištes"; the župas and krajištes were one and the same, where župas on the borders were called krajištes (frontier).[20] The župa consisted of villages, and their status, rights, and obligations were regulated in the constitution. The ruling nobility possessed hereditary allodial estates, which were worked by dependent sebri, the equivalent of Greek paroikoi: peasants owing labour services, formally bound by decree. The earlier župan title was abolished and replaced with the Greek-derived kefalija (kephale, "head, master").[21]

Economy

Commerce was another object of Dušan's concern. He gave strict orders to combat piracy and to assure the safety of travelers and foreign merchants. Traditional relations with Venice were resumed, with the port of Ragusa (Dubrovnik) becoming an important transaction point. Exploitation of mines produced appreciable resources.

East-west Roman roads through the empire carried a variety of commodities: wine, manufactures, and luxury goods from the coast; metals, cattle, timber, wool, skins, and leather from the interior. This economic development made possible the creation of the Empire. Important trade routes were the ancient Roman Via Militaris, Via Egnatia, Via de Zenta, and the Kopaonik road, among others. Ragusan merchants in particular had trading privileges throughout the realm. Security of trade and merchants on the roads was a major concern for the state authorities.[22]

Srebrenica, Rudnik, Trepča, Novo Brdo, Kopaonik, Majdanpek, Brskovo, and Samokov were the main centers for mining iron, copper, and lead ores, and silver and gold placers.[23] The silver mines provided much of the royal income, and were worked by slave-labour, managed by Saxons.[24][25] A colony of Saxons worked the Novo Brdo mines and traded charcoal burners. The silver mines processed an annual 0.5 million dollars (1919 comparation).[26]

The currency used was called dinars; an alternative name was perper, derived from the Byzantine hyperpyron. The golden dinar was the largest unit, and the imperial tax was one dinar coin, per house, annually.[27]

Military

Serbian military tactics consisted of wedge-shaped heavy cavalry attacks with horse archers on the flanks. Many foreign mercenaries were in the Serbian army, mostly Germans as cavalry and Spaniards as infantry. The army also had personal mercenary guards for the emperor, mainly German knights. A German nobleman, Palman, became the commander of the Serbian "Alemannic Guard" in 1331 upon crossing Serbia on the way to Jerusalem; he became leader of all mercenaries in the Serbian Army. The main strength of the Serbian army were the heavily armoured knights feared for their ferocious charge and fighting skills, as well as hussars, versatile light cavalry formations armed mainly with spears and crossbows, ideal for scouting, raiding and skirmishing.

State insignia

The 1339 map by Angelino Dulcert depicts a number of flags, and Serbia is represented by a flag placed above Skoplje (Skopi) with the name Serbia near the hoist, which was characteristic for capital cities at the time the drawing was produced. The flag, depicting a red double-headed eagle, represented the realm of Stefan Dušan.[28][29] A flag in Hilandar, seen by Dimitrije Avramović, was alleged by the brotherhood to have been a flag of Emperor Dušan; it was a triband with red at the top and bottom and white in the center.[30] Emperor Dušan also adopted the Imperial divelion, which was purple and had a golden cross in the center.[31] Another of Dušan's flags was the Imperial cavalry flag, kept at the Hilandar monastery on Mount Athos; a triangular bicolored flag, of red and yellow.[32]

Gallery

-

Flag of Serbia on the map of Angelino Dulcert (1339).

-

Reconstruction based on Dulcert's map

-

Emperor Dušan's Divellion

-

Imperial cavalry flag, Hilandar

-

Attributed arms of Serbia from the Fojnica Armorial, manuscript of the late 16th or early 17th century. A modified version of it would later go on to become the coat of arms of the Principality of Serbia and its ruling dynasty.

-

Attributed imperial coat of arms of Stefan Dušan from the Korjenić-Neorić Armorial, manuscript of the late 16th century

-

Alleged flag, Hilandar

-

Serbian Empire in 1358 according to Louis Etienne Dussieux

-

Geographic map of the Serbian Empire overlayed with modern borders

Culture

Religion

Influenced by the clergy, Dušan showed extreme severity towards Roman Catholicism. Those who integrated into the Latin Church were condemned to work in mines, and people who propagated it were threatened with death. The Papacy grew concerned about this and the increasing power of Dušan and aroused the old rivalry of the Catholic Hungarians against the Orthodox Serbs. Once again Dušan overcame his enemies from whom he seized Bosnia and Herzegovina, which marked the height of the Serbian Empire in Middle Ages. However, the most serious menace came from the East, from the Turks. Entrenched on the shores of the Dardanelles, the Turks were the common enemies of Christendom. It was against them that the question of uniting and directing all forces in the Balkans to save Europe from the invasion arose. The Serbian Empire already included most of the region, and to transform the peninsula into a cohesive whole under a rule of a single master required seizure of Constantinople to add to Serbia what remained of the Byzantine Empire. Dušan intended to make himself emperor and defender of Christianity against the Islamic wave.[33]

Education and arts

Education, to which St. Sava had given the first impulse, progressed remarkably during Dušan's reign. Schools and monasteries secured royal favor. True seats of culture, they became institutions in perpetuating Serbian national traditions. The fine arts, influenced by Italians, were not neglected. Architectural monuments, frescoes and mosaics testify the artistic level archived during this period.[34][35]

Government

- Emperors, and co-rulers

- Stefan Dušan (1346–1355)

- Stefan Uroš V (1355–1371)

- co-ruler Vukašin of Serbia with the title of "king" (1365–1371)[36]

- designated heir Prince Marko with the title of "young king" (1369–1371)

- co-ruler Vukašin of Serbia with the title of "king" (1365–1371)[36]

For a list of magnates, feudal lords and officials, see Nobility of the Serbian Empire.

See also

References

- ^ David Nicolle; (1988) Hungary and the Fall of Eastern Europe 1000–1568 (Men-at-Arms) pp. 35, 37; Osprey Publishing, ISBN 0850458331

- ^ Positive Peace in Kosovo: A Dream Unfulfilled by Elisabeth Schleicher, p. 49. 2012

- ^ Dvornik 1962, pp. 111–114.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 286–382.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 63–80.

- ^ a b Fine 1994, p. 309.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Ostrogorsky 1956, p. 468.

- ^ Steven Runciman (26 March 2012). The Fall of Constantinople 1453. Cambridge University Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-1-107-60469-8.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 272.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 274.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 78–80.

- ^ Blagojević 1993, pp. 20–31.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 314–317.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 67–71.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 116, 118.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 43, 68.

- ^ Krstić 1993, pp. 188–195.

- ^ Radovanović, M. 2002, "Šar mountain and its župas in South Serbia's Kosovo-Metohia region: Geographical position and multiethnic characteristics", Zbornik radova Geografskog instituta "Jovan Cvijić", SANU, no. 51, pp. 7–22[permanent dead link]; p. 5

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Sophoulis 2020, pp. 39–55.

- ^ Kovačević-Kojić 2014, pp. 97–106.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 199–200, 316, 626.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 54–55, 71, 123.

- ^ National City Bank of New York (2002). JOM: the journal of the Minerals, Metals & Materials Society. Vol. 6. Society (TMS). p. 27.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Solovyev 1958, pp. 134–135

- ^ Gavro A. Škrivanić (1979). Monumenta Cartographica Jugoslaviae 2. Narodna knjiga.

- ^ Stanoje Stanojević (1934). Iz naše prošlosti. Geca Kon. pp. 78–80.

- ^ Milić Milićević (1995). Grb Srbije: razvoj kroz istoriju. Službeni Glasnik. p. 22. ISBN 9788675490470.

- ^ Atlagić, M. (1997). "The cross with symbols S as heraldic symbols" (PDF). Baština, no. 8. pp. 149–158. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-21.

- ^ Dragojlović 1993, pp. 32–40.

- ^ Đurić 1993, pp. 72–89.

- ^ Korać 1993, pp. 90–114.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 77–79.

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Blagojević, Miloš (1993). "On the National Identity of the Serbs in the Middle Ages". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 20–31. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Čanak-Medić, Milka; Todić, Branislav (2017). The Monastery of the Patriarchate of Peć. Novi Sad: Platoneum, Beseda. ISBN 9788685869839.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Ćirković, Sima (2014) [1964]. "The Double Wreath: A Contribution to the History of Kingship in Bosnia". Balcanica (45): 107–143. doi:10.2298/BALC1445107C.

- Dragojlović, Dragoljub (1993). "Serbian Spirituality in the 13th and 14th Centuries and Western Scholasticism". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 32–40. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Đurić, Vojislav J. (1993). "The European Scope of Painting in Medieval Serbia". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 72–89. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Dvornik, Francis (1962). The Slavs in European History and Civilization. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 9780813507996.

- Engel, Pál (2001). The Realm of St. Stephen: A History of Medieval Hungary, 895–1526. London & New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781850439776.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 9781899828340.

- Isailović, Neven (2016). "Living by the Border: South Slavic Marcher Lords in the Late Medieval Balkans (13th–15th Centuries)". Banatica. 26 (2): 105–117.

- Isailović, Neven (2017). "Legislation Concerning the Vlachs of the Balkans Before and After Ottoman Conquest: An Overview". State and Society in the Balkans Before and After Establishment of Ottoman Rule. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 25–42. ISBN 9788677431259.

- Ivanović, Miloš; Isailović, Neven (2015). "The Danube in Serbian-Hungarian Relations in the 14th and 15th Centuries". Tibiscvm: Istorie–Arheologie. 5: 377–393.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)". Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 103–129.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Jireček, Constantin (1911). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 1. Gotha: Perthes.

- Jireček, Constantin (1918). Geschichte der Serben. Vol. 2. Gotha: Perthes.

- Korać, Vojislav (1993). "Serbian Architecture Between Byzantium and the West". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 90–114. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Kovačević-Kojić, Desanka (2014). "On the Composition and Processing of Precious Metals mined in Medieval Serbia" (PDF). Balcanica (45): 97–106. doi:10.2298/BALC1445097K.

- Krstić, Đurica (1993). "Serbian Medieval Law and the Development of Law in Subsequent Periods". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 188–195. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Miller, William (1923a). "The Balkan States, I: The Zenith of Bulgaria and Serbia (1186–1355)". The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 517–551.

- Miller, William (1923b). "The Balkan States, II: The Turkish Conquest (1355–1483)". The Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. 4. Cambridge: University Press. pp. 552–593.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1984) [1957]. The Despotate of Epiros 1267–1479: A Contribution to the History of Greece in the Middle Ages (2. expanded ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521261906.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1993) [1972]. The Last Centuries of Byzantium, 1261–1453. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521439916.

- Nicol, Donald M. (1996). The Reluctant Emperor: A Biography of John Cantacuzene, Byzantine Emperor and Monk, c. 1295–1383. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521522014.

- Obolensky, Dimitri (1974) [1971]. The Byzantine Commonwealth: Eastern Europe, 500–1453. London: Cardinal. ISBN 9780351176449.

- Orbini, Mauro (1601). Il Regno de gli Slavi hoggi corrottamente detti Schiavoni. Pesaro: Apresso Girolamo Concordia.

- Орбин, Мавро (1968). Краљевство Словена. Београд: Српска књижевна задруга.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Popović, Tatyana (1988). Prince Marko: The Hero of South Slavic Epics. New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815624448.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Sophoulis, Panos (2020). Banditry in the Medieval Balkans, 800–1500. Cham: Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030559052.

- Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331–1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884021377.

- Uzelac, Aleksandar B. (2015). "Foreign Soldiers in the Nemanjić State – A Critical Overview". Belgrade Historical Review. 6: 69–89.

External links

Media related to Serbian Empire at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serbian Empire at Wikimedia Commons