Election

| Part of the Politics series |

| Elections |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of the Politics series |

| Politics |

|---|

|

|

An election is a formal group decision-making process by which a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated since the 17th century.[1] Elections may fill offices in the legislature, sometimes in the executive and judiciary, and for regional and local government. This process is also used in many other private and business organisations, from clubs to voluntary associations and corporations.

The global use of elections as a tool for selecting representatives in modern representative democracies is in contrast with the practice in the democratic archetype, ancient Athens, where the elections were considered an oligarchic institution and most political offices were filled using sortition, also known as allotment, by which officeholders were chosen by lot.[1]

Electoral reform describes the process of introducing fair electoral systems where they are not in place, or improving the fairness or effectiveness of existing systems. Psephology is the study of results and other statistics relating to elections (especially with a view to predicting future results). Election is the fact of electing, or being elected.

To elect means "to select or make a decision", and so sometimes other forms of ballot such as referendums are referred to as elections, especially in the United States.

History

Elections were used as early in history as ancient Greece and ancient Rome, and throughout the Medieval period to select rulers such as the Holy Roman Emperor (see imperial election) and the pope (see papal election).[2]

In the Vedic period[specify] of India, the raja (king) of a gaṇa (a tribal organization) was elected by the gaṇa. The raja always belonged to the Kshatriya varna (warrior class), and was typically a son of the previous raja. However, the gaṇa members had the final say in his elections.[3] Even during the Sangam Period people elected their representatives by casting their votes and the ballot boxes (usually a pot) were tied by rope and sealed. After the election the votes were taken out and counted.[4][better source needed] The Pala King Gopala (ruled c. 750s – 770s CE) in early medieval Bengal was elected by a group of feudal chieftains. Such elections were quite common in contemporary societies of the region.[5][6] In the Chola Empire, around 920 CE, in Uthiramerur (in present-day Tamil Nadu), palm leaves were used for selecting the village committee members. The leaves, with candidate names written on them, were put inside a mud pot. To select the committee members, a young boy was asked to take out as many leaves as the number of positions available. This was known as the Kudavolai system.[7][8]

The first recorded popular elections of officials to public office, by majority vote, where all citizens were eligible both to vote and to hold public office, date back to the Ephors of Sparta in 754 BC, under the mixed government of the Spartan Constitution.[9][10] Athenian democratic elections, where all citizens could hold public office, were not introduced for another 247 years, until the reforms of Cleisthenes.[11] Under the earlier Solonian Constitution (c. 574 BC), all Athenian citizens were eligible to vote in the popular assemblies, on matters of law and policy, and as jurors, but only the three highest classes of citizens could vote in elections. Nor were the lowest of the four classes of Athenian citizens (as defined by the extent of their wealth and property, rather than by birth) eligible to hold public office, through the reforms of Solon.[12][13] The Spartan election of the Ephors, therefore, also predates the reforms of Solon in Athens by approximately 180 years.[14]

Questions of suffrage, especially suffrage for minority groups, have dominated the history of elections. Males, the dominant cultural group in North America and Europe, often dominated the electorate and continue to do so in many countries.[2] Early elections in countries such as the United Kingdom and the United States were dominated by landed or ruling class males.[2] However, by 1920 all Western European and North American democracies had universal adult male suffrage (except Switzerland) and many countries began to consider women's suffrage.[2] Despite legally mandated universal suffrage for adult males, political barriers were sometimes erected to prevent fair access to elections (see civil rights movement).[2]

Contexts of elections

Elections are held in a variety of political, organizational, and corporate settings. Many countries hold elections to select people to serve in their governments, but other types of organizations hold elections as well. For example, many corporations hold elections among shareholders to select a board of directors, and these elections may be mandated by corporate law.[15] In many places, an election to the government is usually a competition among people who have already won a primary election within a political party.[16] Elections within corporations and other organizations often use procedures and rules that are similar to those of governmental elections.[17]

Electorate

Suffrage

The question of who may vote is a central issue in elections. The electorate does not generally include the entire population; for example, many countries prohibit those who are under the age of majority from voting. All jurisdictions require a minimum age for voting.

In Australia, Aboriginal people were not given the right to vote until 1962 (see 1967 referendum entry) and in 2010 the federal government removed the rights of prisoners serving for 3 years or more to vote (a large proportion of which were Aboriginal Australians).

Suffrage is typically only for citizens of the country, though further limits may be imposed.

However, in the European Union, one can vote in municipal elections if one lives in the municipality and is an EU citizen; the nationality of the country of residence is not required.

In some countries, voting is required by law. Eligible voters may be subject to punitive measures such as a fine for not casting a vote. In Western Australia, the penalty for a first time offender failing to vote is a $20.00 fine, which increases to $50.00 if the offender refused to vote prior.[18]

Voting population

Historically the size of eligible voters, the electorate, was small having the size of groups or communities of privileged men like aristocrats and men of a city (citizens).

With the growth of the number of people with bourgeois citizen rights outside of cities, expanding the term citizen, the electorates grew to numbers beyond the thousands. Elections with an electorate in the hundred thousands appeared in the final decades of the Roman Republic, by extending voting rights to citizens outside of Rome with the Lex Julia of 90 BC, reaching an electorate of 910,000 and estimated voter turnout of maximum 10% in 70 BC,[19] only again comparable in size to the first elections of the United States. At the same time the Kingdom of Great Britain had in 1780 about 214,000 eligible voters, 3% of the whole population.[20]

Candidates

A representative democracy requires a procedure to govern nomination for political office. In many cases, nomination for office is mediated through preselection processes in organized political parties.[21]

Non-partisan systems tend to be different from partisan systems as concerns nominations. In a direct democracy, one type of non-partisan democracy, any eligible person can be nominated. Although elections were used in ancient Athens, in Rome, and in the selection of popes and Holy Roman emperors, the origins of elections in the contemporary world lie in the gradual emergence of representative government in Europe and North America beginning in the 17th century. In some systems no nominations take place at all, with voters free to choose any person at the time of voting—with some possible exceptions such as through a minimum age requirement—in the jurisdiction. In such cases, it is not required (or even possible) that the members of the electorate be familiar with all of the eligible persons, though such systems may involve indirect elections at larger geographic levels to ensure that some first-hand familiarity among potential electees can exist at these levels (i.e., among the elected delegates).

Electoral systems

Electoral systems are the detailed constitutional arrangements and voting systems that convert the vote into a political decision.

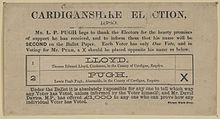

The first step is for voters to cast the ballots, which may be simple single-choice ballots, but other types, such as multiple choice or ranked ballots may also be used. Then the votes are tallied, for which various vote counting systems may be used. and the voting system then determines the result on the basis of the tally. Most systems can be categorized as either proportional, majoritarian or mixed. Among the proportional systems, the most commonly used are party-list proportional representation (list PR) systems, among majoritarian are first-past-the-post electoral system (single winner plurality voting) and different methods of majority voting (such as the widely used two-round system). Mixed systems combine elements of both proportional and majoritarian methods, with some typically producing results closer to the former (mixed-member proportional) or the other (e.g. parallel voting).

Many countries have growing electoral reform movements, which advocate systems such as approval voting, single transferable vote, instant runoff voting or a Condorcet method; these methods are also gaining popularity for lesser elections in some countries where more important elections still use more traditional counting methods.

While openness and accountability are usually considered cornerstones of a democratic system, the act of casting a vote and the content of a voter's ballot are usually an important exception. The secret ballot is a relatively modern development, but it is now considered crucial in most free and fair elections, as it limits the effectiveness of intimidation.

Campaigns

When elections are called, politicians and their supporters attempt to influence policy by competing directly for the votes of constituents in what are called campaigns. Supporters for a campaign can be either formally organized or loosely affiliated, and frequently utilize campaign advertising. It is common for political scientists to attempt to predict elections via political forecasting methods.

The most expensive election campaign included US$7 billion spent on the 2012 United States presidential election and is followed by the US$5 billion spent on the 2014 Indian general election.[22]

Election timing

The nature of democracy is that elected officials are accountable to the people, and they must return to the voters at prescribed intervals to seek their mandate to continue in office. For that reason, most democratic constitutions provide that elections are held at fixed regular intervals. In the United States, elections for public offices are typically held between every two and six years in most states and at the federal level, with exceptions for elected judicial positions that may have longer terms of office. There is a variety of schedules, for example, presidents: the President of Ireland is elected every seven years, the President of Russia and the President of Finland every six years, the President of France every five years, President of the United States every four years.

Pre-decided or fixed election dates have the advantage of fairness and predictability. However, they tend to greatly lengthen campaigns, and make dissolving the legislature (parliamentary system) more problematic if the date should happen to fall at a time when dissolution is inconvenient (e.g. when war breaks out). Other states (e.g., the United Kingdom) only set maximum time in office, and the executive decides exactly when within that limit it will actually go to the polls. In practice, this means the government remains in power for close to its full term, and chooses an election date it calculates to be in its best interests (unless something special happens, such as a motion of no-confidence). This calculation depends on a number of variables, such as its performance in opinion polls and the size of its majority.

Rolling elections are elections in which all representatives in a body are elected, but these elections are spread over a period of time rather than all at once. Examples are the presidential primaries in the United States, Elections to the European Parliament (where, due to differing election laws in each member state, elections are held on different days of the same week) and, due to logistics, general elections in Lebanon and India. The voting procedure in the Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic are also a classical example.

In rolling elections, voters have information about previous voters' choices. While in the first elections, there may be plenty of hopeful candidates, in the last rounds consensus on one winner is generally achieved. In today's context of rapid communication, candidates can put disproportionate resources into competing strongly in the first few stages, because those stages affect the reaction of latter stages.

Non-democratic elections

In many of the countries with weak rule of law, the most common reason why elections do not meet international standards of being "free and fair" is interference from the incumbent government. Dictators may use the powers of the executive (police, martial law, censorship, physical implementation of the election mechanism, etc.) to remain in power despite popular opinion in favour of removal. Members of a particular faction in a legislature may use the power of the majority or supermajority (passing criminal laws, and defining the electoral mechanisms including eligibility and district boundaries) to prevent the balance of power in the body from shifting to a rival faction due to an election.[2]

Non-governmental entities can also interfere with elections, through physical force, verbal intimidation, or fraud, which can result in improper casting or counting of votes. Monitoring for and minimizing electoral fraud is also an ongoing task in countries with strong traditions of free and fair elections. Problems that prevent an election from being "free and fair" take various forms.[23]

Lack of open political debate or an informed electorate

The electorate may be poorly informed about issues or candidates due to lack of freedom of the press, lack of objectivity in the press due to state or corporate control, and/or lack of access to news and political media. Freedom of speech may be curtailed by the state, favouring certain viewpoints or state propaganda.

Unfair rules

Gerrymandering, exclusion of opposition candidates from eligibility for office, needlessly high restrictions on who may be a candidate, like ballot access rules, and manipulating thresholds for electoral success are some of the ways the structure of an election can be changed to favour a specific faction or candidate. Scheduling frequent elections can also lead to voter fatigue.

Interference with campaigns

Those in power may arrest or assassinate candidates, suppress or even criminalize campaigning, close campaign headquarters, harass or beat campaign workers, or intimidate voters with violence. Foreign electoral intervention can also occur, with the United States interfering between 1946 and 2000 in 81 elections and Russia/USSR in 36.[24] In 2018 the most intense interventions, utilizing false information, were by China in Taiwan and by Russia in Latvia; the next highest levels were in Bahrain, Qatar and Hungary.[25]

Tampering with the election mechanism

This can include falsifying voter instructions,[26] violation of the secret ballot, ballot stuffing, tampering with voting machines,[27] destruction of legitimately cast ballots,[28] voter suppression, voter registration fraud, failure to validate voter residency, fraudulent tabulation of results, and use of physical force or verbal intimation at polling places. Other examples include persuading candidates not to run, such as through blackmailing, bribery, intimidation or physical violence.

Sham election

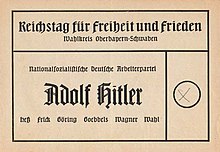

A sham election, or show election, is an election that is held purely for show; that is, without any significant political choice or real impact on the results of the election.[29]

Sham elections are a common event in dictatorial regimes that feel the need to feign the appearance of public legitimacy. Published results usually show nearly 100% voter turnout and high support (typically at least 80%, and close to 100% in many cases) for the prescribed candidate(s) or for the referendum choice that favours the political party in power. Dictatorial regimes can also organize sham elections with results simulating those that might be achieved in democratic countries.[30]

Sometimes, only one government-approved candidate is allowed to run in sham elections with no opposition candidates allowed, or opposition candidates are arrested on false charges (or even without any charges) before the election to prevent them from running.[31][32][33]

Ballots may contain only one "yes" option, or in the case of a simple "yes or no" question, security forces often persecute people who pick "no", thus encouraging them to pick the "yes" option. In other cases, those who vote receive stamps in their passport for doing so, while those who did not vote (and thus do not receive stamps) are persecuted as enemies of the people.[34][35]

Sham elections can sometimes backfire against the party in power, especially if the regime believes they are popular enough to win without coercion or fraud. The most famous example of this was the 1990 Myanmar general election, in which the government-sponsored National Unity Party suffered a landslide defeat by the opposition National League for Democracy and consequently, the results were annulled.[36]

Examples of sham elections include: the presidential and parliamentary elections of the Islamic Republic of Iran,[37] the 1929 and 1934 elections in Fascist Italy, the 1942 general election in Imperial Japan, those in Nazi Germany, East Germany, the 1940 elections of Stalinist "People's Parliaments" to legitimise the Soviet occupation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the 1928, 1935, 1942, 1949, 1951 and 1958 elections in Portugal, the 1991 and 2019 Kazakh presidential elections, those in North Korea,[38] the 1995 and 2002 presidential referendums in Saddam Hussein's Iraq and the 2021 Hong Kong legislative election.[39]

In Mexico, all of the presidential elections from 1929 to 1982 are considered to be sham elections, as the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) and its predecessors governed the country in a de facto single-party system without serious opposition, and they won all of the presidential elections in that period with more than 70% of the vote. The first seriously competitive presidential election in modern Mexican history was that of 1988, in which for the first time the PRI candidate faced two strong opposition candidates, though it is believed that the government rigged the result. The first fair election was held in 1994, though the opposition did not win until 2000.

A predetermined conclusion is permanently established by the regime through suppression of the opposition, coercion of voters, vote rigging, reporting several votes received greater than the number of voters, outright lying, or some combination of these. In an extreme example, Charles D. B. King of Liberia was reported to have won by 234,000 votes in the 1927 general election, a "majority" that was over fifteen times larger than the number of eligible voters.[40]

Elections as aristocratic

Scholars argue that the predominance of elections in modern liberal democracies masks the fact that they are actually aristocratic selection mechanisms[41] that deny each citizen an equal chance of holding public office. Such views were expressed as early as the time of Ancient Greece by Aristotle.[41] According to French political scientist Bernard Manin, the inegalitarian nature of elections stems from four factors: the unequal treatment of candidates by voters, the distinction of candidates required by choice, the cognitive advantage conferred by salience, and the costs of disseminating information.[42] These four factors result in the evaluation of candidates based on voters' partial standards of quality and social saliency (for example, skin color and good looks). This leads to self-selection biases in candidate pools due to unobjective standards of treatment by voters and the costs (barriers to entry) associated with raising one's political profile. Ultimately, the result is the election of candidates who are superior (whether in actuality or as perceived within a cultural context) and objectively unlike the voters they are supposed to represent.[42]

Additionally, evidence suggests that the concept of electing representatives was originally conceived to be different from democracy.[43] Prior to the 18th century, some societies in Western Europe used sortition as a means to select rulers, a method which allowed regular citizens to exercise power, in keeping with understandings of democracy at the time.[44] However, the idea of what constituted a legitimate government shifted in the 18th century to include consent, especially with the rise of the enlightenment. From this point onwards, sortition fell out of favor as a mechanism for selecting rulers. On the other hand, elections began to be seen as a way for the masses to express popular consent repeatedly, resulting in the triumph of the electoral process until the present day.[45]

This conceptual misunderstanding of elections as open and egalitarian when they are not innately so may thus be a root cause of the problems in contemporary governance.[46] Those in favor of this view argue that the modern system of elections was never meant to give ordinary citizens the chance to exercise power - merely privileging their right to consent to those who rule.[47] Therefore, the representatives that modern electoral systems select for are too disconnected, unresponsive, and elite-serving.[48][49][50][51] To deal with this issue, various scholars have proposed alternative models of democracy, many of which include a return to sortition-based selection mechanisms. The extent to which sortition should be the dominant mode of selecting rulers[49] or instead be hybridised with electoral representation[52] remains a topic of debate.

See also

- Ballot access

- Concession (politics)

- Demarchy — "democracy without elections"

- Electoral calendar

- Electoral integrity

- Electoral system

- Election law

- Election litter

- Elections by country

- Electronic voting

- Fenno's paradox

- Full slate

- Garrat Elections

- Gerontocracy

- Issue voting

- Landslide election

- Meritocracy

- Multi-party system

- Nomination rules

- Party system

- Pluralism (political philosophy)

- Political polarization

- Political science

- Polling station

- Proportional representation

- Re-election

- Slate

- Stunning elections

- Two-party system

- Voter turnout

- Voting system

References

- ^ a b Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–7. ISBN 9780511659935.

- ^ a b c d e f "Election (political science)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 18 August 2009

- ^ Eric W. Robinson (1997). The First Democracies: Early Popular Government Outside Athens. Franz Steiner Verlag. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-3-515-06951-9.

- ^ Agananooru. Chennai: Saiva Siddantha Noor pathippu Kazhagam. 1968. pp. 183–186.

- ^ Nitish K. Sengupta (1 January 2011). "The Imperial Palas". Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. pp. 39–49. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.

- ^ Biplab Dasgupta (1 January 2005). European Trade and Colonial Conquest. Anthem Press. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-1-84331-029-7.

- ^ VK Agnihotri, ed. (2010). Indian History (26th ed.). Allied. pp. B-62–B-65. ISBN 978-81-8424-568-4.

- ^ "Pre-Independence Method of Election". Tamil Nadu State Election Commission, India. Archived from the original on 29 October 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Ephor | Spartan magistrate".

- ^ Herodotus. The Histories. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Ancient Greek Democracy".

- ^ "Birth of Democracy: Solon the Lawgiver".

- ^ Aristotle. The Constitution of Athens. Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "Solon | Biography, Reforms, Importance, & Facts".

- ^ Cai, J.; Garner, J. L.; Walkling, R. A. (2009). "Electing Directors". Journal of Finance. 64 (5): 2387–2419. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2009.01504.x. S2CID 6133226.

- ^ Sandri, Giulia; Seddone, Antonella (11 September 2015). Party Primaries in Comparative Perspective. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 9781472450388.

- ^ Glazer, Amihai; Glazer, Debra G.; Grofman, Bernard (1984). "Cumulative Voting in Corporate Elections: Introducing Strategy into the Equation". South Carolina Law Review. 35 (2): 295–311.

- ^ "Failure to Vote | Western Australian Electoral Commission". www.elections.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 26 November 2018.

- ^ Vishnia 2012, p. 125

- ^ "Exhibitions > Citizenship > The struggle for democracy > Getting the vote > Voting rights before 1832". The National Archives. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Reuven Hazan, 'Candidate Selection', in Lawrence LeDuc, Richard Niemi and Pippa Norris (eds), Comparing Democracies 2, Sage Publications, London, 2002

- ^ "India's spend on elections could challenge US record: report". NDTV.com. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- ^ "Free and Fair Elections". Public Sphere Project. 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- ^ Levin, Dov H. (June 2016). "When the Great Power Gets a Vote: The Effects of Great Power Electoral Interventions on Election Results". International Studies Quarterly. 60 (2): 189–202. doi:10.1093/isq/sqv016.

- ^ Democracy Facing Global Challenges, V-Dem Annual Democracy Report 2019, p.36 (PDF) (Report). 14 May 2019. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ 2018-2019 San Mateo County Civil Grand Jury (24 July 2019). "Security of Election Announcements" (PDF). Superior Court of California. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Zetter, Kim (26 September 2018). "The Crisis of Election Security". The New York Times Magazine. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 2112081778. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ Gardner, Amy (21 February 2019). "N.C. board declares a new election in contested House race after the GOP candidate admitted he was mistaken in his testimony". The Washington Post. Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- ^ "Sham Election Law and Legal Definition". USLegal, Inc. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Kim Jong-un wins 100% of the vote in his constituency". The Independent. 10 March 2014.

- ^ Jamjoom, Mohammed (21 February 2012). "Yemen holds presidential election with one candidate". CNN.

- ^ Sanchez, Raf; Samaan, Magdy (29 January 2018). "Egyptian opposition calls for boycott of elections after challengers are arrested and attacked". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "Russia: Justice in The Baltic". Time. 19 August 1940. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Yes, There Are Elections in North Korea and Here's How They Work - The Atlantic". The Atlantic. 6 March 2014.

- ^ "Burma: 20 Years After 1990 Elections, Democracy Still Denied". Human Rights Watch. 26 May 2010. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- ^ "Why Does The Islamic Republic Of Iran Hold Elections?". Radio Farda. 20 February 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2023.

- ^ Emily Rauhala (10 March 2014). "Inside North Korea's sham election". Time. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ^ "Hong Kong Imposes Sham Election". Human Rights Watch. 17 December 2021. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ "Liberia past and present 1927 elections".

- ^ a b Ferejohn, John; Rosenbluth, Frances (2010). "10". In Shapiro, Ian; Stokes, Susan C.; Wood, Elisabeth Jean; Kirshner, Alexander S. (eds.). Political Representation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511813146.

- ^ a b Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–149. ISBN 9780511659935.

- ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 9780511659935.

- ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780511659935.

- ^ Manin, Bernard (1997). The Principles of Representative Government. Cambridge University Press. pp. 79–93. ISBN 9780511659935.

- ^ Landemore, Hélène (2020). Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0691181998.

- ^ Landemore, Hélène (2020). "Prologue". Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. pp. xiv. ISBN 978-0691181998.

- ^ Ferejohn, John; Rosenbluth, Frances (2010). "10". In Shapiro, Ian; Stokes, Susan C.; Wood, Elisabeth Jean; Kirshner, Alexander S. (eds.). Political Representation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780511813146.

- ^ a b Landemore, Hélène (2020). Open Democracy: Reinventing Popular Rule for the Twenty-First Century. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691181998.

- ^ Reybrouck, David Van (2016). Against Elections: The Case for Democracy. Random House UK. ISBN 978-1847924223.

- ^ Guerrero, Alexander A. (26 August 2014). "Against Elections: The Lottocratic Alternative". Philosophy and Public Affairs. 42 (2): 135–178. doi:10.1111/papa.12029 – via Wiley Online Library.

- ^ Gastil, John; Wright, Erik Olin (2019). Legislature by Lot: Transformative Designs for Deliberative Governance. Verso. ISBN 9781788736084.

Bibliography

- Arrow, Kenneth J. 1963. Social Choice and Individual Values. 2nd ed. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Benoit, Jean-Pierre and Lewis A. Kornhauser. 1994. "Social Choice in a Representative Democracy". American Political Science Review 88.1: 185–192.

- Corrado Maria, Daclon. 2004. US Elections and War On Terrorism – Interview With Professor Massimo Teodori Analisi Difesa, n. 50

- Farquharson, Robin. 1969. A Theory of Voting. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Mueller, Dennis C. 1996. Constitutional Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Owen, Bernard, 2002. "Le système électoral et son effet sur la représentation parlementaire des partis: le cas européen", LGDJ;

- Riker, William. 1980. Liberalism Against Populism: A Confrontation Between the Theory of Democracy and the Theory of Social Choice. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.

- Thompson, Dennis F. 2004. Just Elections: Creating a Fair Electoral Process in the U.S. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226797649

- Ware, Alan. 1987. Citizens, Parties and the State. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 169–172.

Election counts

- PARLINE database on national parliaments. Results for all parliamentary elections since 1966

- "Psephos", archive of recent electoral data from 182 countries

- ElectionGuide.org — Worldwide Coverage of National-level Elections

- parties-and-elections.de: Database for all European elections since 1945

- Angus Reid Global Monitor: Election Tracker

Election organizations

- ACE Electoral Knowledge Network — electoral encyclopedia and related resources from a consortium of electoral agencies and organizations.

- International Foundation for Electoral Systems

- International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance

- European Conferences of Electoral Management Bodies (Council of Europe)

- OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR)

- European Election Law Association (Eurela), closed in 2008

- List of Local Elected Offices in the United States

- Caltech/ MIT Voting Technology Project