Supreme Leader of Afghanistan

| Supreme Leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Leadership of the Islamic Emirate | |

| Style | |

| Type | Supreme leader |

| Status | Head of state |

| Member of | Leadership Council |

| Residence | None official[2] |

| Seat | Kandahar |

| Appointer | Leadership Council |

| Term length | Life tenure |

| Constituting instrument | 1998 dastur |

| Precursor | President of Afghanistan |

| Inaugural holder | Mullah Omar |

| Formation | 15 August 2021 (current form) 4 April 1996 (originally) |

| Deputy | Deputy Leader |

| Salary | ؋228,750 monthly |

|

|---|

|

|

The supreme leader of Afghanistan[3] (Template:Lang-ps, Template:Lang-prs), officially the supreme leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan[4][5][note 1] and also styled by his religious title Amir al-Mu'minin (Arabic, lit. 'Commander of the Faithful'), is the absolute ruler, head of state, and national religious leader of Afghanistan, as well as the leader of the Taliban.[10][11][12] The supreme leader wields unlimited authority and is the ultimate source of all law.[12][13][14]

The first supreme leader, Mullah Omar, ruled Afghanistan from 1996 to 2001 before his government was overthrown by the United States and he was forced into exile. The current supreme leader is Hibatullah Akhundzada, who assumed office in exile during the Taliban insurgency on 25 May 2016, upon being chosen by the Leadership Council, and came to power on 15 August 2021 with the Taliban's victory over U.S.-backed forces in the 2001–2021 war. Since coming to power, Akhundzada has issued numerous decrees that have profoundly reshaped government and daily life in Afghanistan by implementing his strict interpretation of the Hanafi school of Sharia law.

The supreme leader appoints and manages the activities of the prime minister and other members of the Cabinet, as well as judges and provincial and local leaders.[12]

History

The office was established by Mullah Mohammed Omar, who founded both the Taliban and the original Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan in the 1990s. On 4 April 1996, in Kandahar, followers of Omar bestowed upon him the title Amir al-Mu'minin (أمير المؤمنين), meaning "Commander of the Faithful", as Omar had donned a cloak taken from its shrine in the city, asserted to be that of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.[15][16] The Taliban seized control of Kabul on 27 September 1996, ousting President Burhanuddin Rabbani and installing Omar as the country's head of state.[17]

The Taliban views the Quran as its constitution. However, it approved a dastur, a document akin to a basic law, in 1998, which proclaimed Omar supreme leader but did not outline a succession process. In 1996 interview, Wakil Ahmed Muttawakil stated that the Amir al-Mu'minin is "only for Afghanistan", rather than a caliph claiming leadership of all Muslims worldwide.[18][19]

Following the September 11 attacks and the United States invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, Omar was deposed and went into hiding in Zabul Province, and the presidency was restored as Afghanistan's head of state. The Taliban reorganized for an insurgency in 2002, based out of Pakistan. They continued to claim Omar as their supreme leader, though he had little involvement in the insurgency, having turned over operational control to his deputies.[20] Though the Taliban continued to maintain the office of the supreme leader in exile, it had no diplomatic recognition.

Following its offensive in 2021, the Taliban recaptured Kabul on 15 August and restored the supreme leader as Afghanistan's head of state.[21][22][23][11]

Selection

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

The supreme leader is appointed by the Leadership Council.[24]

Powers and duties

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (August 2021) |

Under Omar, the leader held absolute power, and the Taliban's interpretation of Sharia was entirely his decision.

Under the 1998 draft constitution of the first Islamic Emirate, the Leader of the Faithful would appoint justices of the Supreme Court.[25]

Under the current government however, the Emir has final authority on political appointments, as well as political, religious, and military affairs. The Emir carries out much of his work through the Rabbari Shura, or the Leadership Council (which he chairs[26]), based in Kandahar, which oversees the work of the Cabinet, and appointment of individuals to key posts within the cabinet.[27]

However, in a report from Al Jazeera, the Cabinet has no authority, with all decisions being made confidentiality by Akhundzada and the Leadership Council.[28] The supreme leader receives the highest government salary in the reinstated Islamic Emirate, at 228,750 Afghan afghanis monthly.[29]

List of supreme leaders

- Status

| No. | Name (Birth–death) |

Additional position(s) held | Term of office (including in exile) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Took office | Left office | Time in office | ||||

| 1 | Mullah Mohammed Omar (died 2013) |

– | 4 April 1996 Ruler of Afghanistan from 27 September 1996 |

23 April 2013 Ruler of Afghanistan until 13 November 2001 |

17 years, 19 days Ruler of Afghanistan for 5 years, 47 days |

[15][30][31] |

| 2 | Mullah Akhtar Mansour (1960s–2016) |

First Deputy Leader (2010–2015) | 23 April 2013 | 29 July 2015 | 2 years, 97 days[note 2] | [32][33][34] |

| – | 29 July 2015 | 21 May 2016 | 297 days | |||

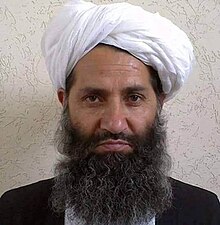

| 3 | Sheikh al-Hadith Mullah Mawlawi Hibatullah Akhundzada |

First Deputy Leader (2015–2016) and Chief Justice (2001–2016) |

21 May 2016 | 25 May 2016 | 4 days | [35][36][11] |

| – | 25 May 2016 Ruler of Afghanistan since 15 August 2021 |

Incumbent | 8 years, 189 days Ruler of Afghanistan for 3 years, 107 days | |||

Timeline

Deputy Leader

| Deputy Leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan | |

|---|---|

| |

Incumbents

| |

| Leadership of the Islamic Emirate | |

| Status | Deputy head of state |

| Member of | Leadership Council[37] |

| Reports to | Supreme Leader[38] |

| Seat | Kandahar (Yaqoob)[39] |

| Appointer | Supreme Leader |

| Term length | At the pleasure of the supreme leader |

| Precursor | Vice President of Afghanistan |

| Inaugural holder | Mohammad Rabbani[40] |

| Formation | 15 August 2021 (current form) 4 April 1996 (originally) |

| Succession | Acting (in order of deputy rank)[32][41] |

The deputy leader of Afghanistan, officially the deputy leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (Template:Lang-ps,[42][romanization needed] Template:Lang-prs[43][romanization needed]), is the deputy emir of the Taliban, tasked with assisting the supreme leader with his duties.[44][38] All three supreme leaders of the Taliban have had deputies, with the number of deputies fluctuating between one and three.[45] Akhundzada has three deputies: Sirajuddin Haqqani, Mullah Yaqoob, and Abdul Ghani Baradar. Haqqani was first appointed as a deputy leader by Akhtar Mansour in 2015, and was retained by Akhundzada. Upon assuming office in 2016, Akhundzada appointed Yaqoob, a son of Mullah Omar, as a second deputy. Akhundzada appointed Baradar as a third deputy in 2019.[46]

Since the 2021 return of power to the Taliban, Akhundzada has grown more isolated and he has primarily communicated through his three deputies rather than holding meetings with other Taliban leaders. The deputies' exclusive access to Akhundzada has grown their power.[13][47]

See also

- Government of Afghanistan

- History of Afghanistan

- List of heads of state of Afghanistan

- List of Taliban insurgency leaders

- Politics of Afghanistan

- President of Afghanistan

- Supreme Leader of Iran

- Supreme Leader (North Korean title)

Notes

- ^ Template:Lang-ps,[6][7] Template:Lang-prs[8][9]

- ^ Mullah Omar's death was concealed from the public and most of the Taliban. The same day news of Omar's death became public, Mansour was elected Supreme Leader.

References

- ^ a b c "Acting Minister of Education Meets Esteemed Amir-ul-Momineen". Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan – Voice of Jihad. Kandahar. 8 February 2022. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Constable, Pamela (4 June 2023). "Taliban moving senior officials to Kandahar. Will it mean a harder line?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 June 2023.

- ^ "Afghan supreme leader orders full implementation of sharia law". Agence France-Presse. Kabul. The Guardian. 14 November 2022. Retrieved 27 November 2022.

- ^ "Message of Amir-ul-Mumineen Sheikh-ul-Hadith Hibatullah Akhundzadah, the Supreme Leader of IEA on the Arrival of Eid-ul-Fitr – Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan". Retrieved 29 April 2022.

- ^ "IEA leader gives order to round up Kabul beggars, provide them with jobs | Ariana News". www.ariananews.af. 8 August 2022. Retrieved 12 August 2022.

- ^ "Hibatullah Akhundzada reiterates his commitment to amnesty". The Killid Group (in Pashto). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "IEA's supreme leader calls on officials to adhere to amnesty orders". Ariana News (in Pashto). 30 December 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "IEA takes massive anti-drug step, bans poppy cultivation". Ariana News (in Dari). 3 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "Taliban leadership council meets". The Killid Group (in Dari). 1 September 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Ramachandran, Sudha (10 September 2021). "What Role Will the Taliban's 'Supreme Leader' Play in the New Government?". The Diplomat. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Faulkner, Charlie (3 September 2021). "Spiritual leader is Afghanistan's head of state — with bomb suspect set to be PM". The Times. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- ^ a b c Dawi, Akmal (28 March 2023). "Unseen Taliban Leader Wields Godlike Powers in Afghanistan". Voice of America. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ a b T. S. Tirumurti (26 May 2022). "Letter dated 25 May 2022 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee established pursuant to resolution 1988 (2011) addressed to the President of the Security Council" (PDF). United Nations Security Council. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ Kraemer, Thomas (27 November 2022). "Afghanistan dispatch: Taliban leaders issue new orders on law-making process, enforcement of court orders from previous government". JURIST. Retrieved 1 May 2023.

- ^ a b Weiner, Tim (7 September 2001). "Man in the News; Seizing the Prophet's Mantle: Muhammad Omar". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ "Kandahar residents feel betrayed". www.sfgate.com. 19 December 2001. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Afghan forces routed as Kabul falls". BBC News. 27 September 1996. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Osman, Borhan; Gopal, Anand (July 2016). "Taliban Views on a Future State" (PDF). Center on International Cooperation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ Ahmad, Javid (26 January 2022). "The Taliban's religious roadmap for Afghanistan". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ^ Dam, Bette (2019). "The Secret Life of Mullah Omar" (PDF). Zomia Center. Retrieved 11 May 2023.

- ^ Mistlin, Alex; Sullivan, Helen; Harding, Luke; Harding, Luke; Borger, Julian; Mason, Rowena (15 August 2021). "Afghanistan: Kabul to shift power to 'transitional administration' after Taliban enter city – live updates". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Heavy fighting ongoing on the outskirts of Kabul as of early Aug. 15; a total blackout reported in the city". Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ "Taliban officials: there will be no transitional government in Afghanistan". Reuters. 15 August 2021. Archived from the original on 15 August 2021. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Burke, Jason (17 August 2021). "The Taliban leaders in line to become de facto rulers of Afghanistan". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Beyond Republic or Emirate: Afghan Constitutional System at Crossroads". www.iconnectblog.com. Archived from the original on 17 August 2021. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ "Three-day meeting of the Leadership Council of Islamic Emirate headed by esteemed Amir-ul-mumineen held in Kandahar". Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. 31 August 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "What Role Will the Taliban's 'Supreme Leader' Play in the New Government?". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Latifi, Ali M. "Taliban divisions deepen as hardliners seek spoils of war". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Hakimi, Amina (5 December 2021). "Senior Officials' Salaries Reduced: MoF". TOLOnews. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Who's who in the Taliban leadership". BBC News. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ CNN Umair (29 July 2015). "Mullah Omar: Life chapter of Taliban's supreme leader comes to end". ireport.cnn.com. Faisalabad, Pakistan: CNN. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2021.

{{cite news}}:|author1=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Goldstein, Joseph (4 October 2015). "Taliban's New Leader Strengthens His Hold With Intrigue and Battlefield Victory". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Taliban sources - Afghan Taliban appoint Mansour as leader". Reuters. 30 July 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Taliban resignation points to extent of internal divisions in leadership crisis". Agence France-Presse. Kabul. The Guardian. 4 August 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

- ^ "Afghan Taliban announce successor to Mullah Mansour". BBC News. 25 May 2016. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- ^ Mellen, Ruby (3 September 2021). "The Taliban has decided on its government. Here's who could lead the organization". The Washington Post. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Jones, Seth G. (December 2020). "Afghanistan's Future Emirate? The Taliban and the Struggle for Afghanistan". CTC Sentinel. 13 (11). Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ a b Sayed, Abdul (8 September 2021). "Analysis: How Are the Taliban Organized?". Voice of America. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

This leadership structure remains in place, with Shaikh Hibatullah Akhundzada serving as supreme leader, aided by the three deputies

- ^ Inskeep, Steve; Qazizai, Fazelminallah (5 August 2022). "We visited a Taliban leader's compound to examine his vision for Afghanistan". NPR. Kandahar. Retrieved 8 May 2023.

- ^ Elias, Barbara. "The Taliban Biography – Documents on the Structure and Leadership of the Taliban 1996-2002" (PDF). National Security Archive. George Washington University. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ O'Donnell, Lynne; Khan, Mirwais (29 May 2020). "Taliban Leadership in Disarray on Verge of Peace Talks". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- ^ Mujahid, Zabiullah [@Zabehulah_M33] (24 February 2019). د اسلامي امارت مرستیال او د سیاسي دفتر مشر محترم ملاعبدالغني برادر پخیر سره دوحې ته ورسید [The Deputy Leader of the Islamic Emirate and Head of the Political Office, Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar Pakhir arrived in Doha.] (Tweet) (in Pashto). Retrieved 22 April 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Shaheen, Suhail [@suhailshaheen1] (20 May 2020). معاون امارت اسلامی محترم ملا برادر اخند و هیئت همراهش با داکتر زلمی خلیلزاد و هیئت همراهش چند نشست پی هم نمود [The Deputy Leader of the Islamic Emirate, Mullah Baradar Akhund, and his accompanying delegation met several times with Dr. Zalmai Khalilzad and his accompanying delegation.] (Tweet) (in Dari). Retrieved 22 April 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ Seldin, Jeff (20 March 2022). "How Afghanistan's Militant Groups Are Evolving Under Taliban Rule". Voice of America. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

Haqqani has a $10 million bounty on his head from the U.S. government and works as a deputy emir of the Taliban

- ^ Ruttig, Thomas (March 2021). "Have the Taliban Changed?". CTC Sentinel. 14 (3). Combating Terrorism Center. Archived from the original on 11 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- ^ Sayed, Abdul (8 September 2021). "Analysis: How Are the Taliban Organized?". Voice of America. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ CNN International PR [@cnnipr] (16 May 2022). "In an exclusive interview CNN's chief international anchor @amanpour spoke with one of the Taliban's top leaders Sirajuddin Haqqani" (Tweet). Retweeted by Christiane Amanpour. Kabul. Retrieved 6 May 2023 – via Twitter.

{{cite web}}:|author1=has generic name (help)