Tughlaq dynasty

Tughlaq Dynasty (Delhi Sultanate) | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1320–1413[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

![Territory under Tughlaq dynasty of Delhi Sultanate, 1330-1335 AD. The empire shrank after 1335 AD.[5][6]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Map_of_the_Tughlaqs.png/275px-Map_of_the_Tughlaqs.png) Territory under Tughlaq dynasty of Delhi Sultanate, 1330-1335 AD. The empire shrank after 1335 AD.[5][6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Delhi | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Persian (official)[7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Sultanate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1320–1325 | Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1325–1351 | Muhammad ibn Tughluq | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1351–1388 | Firuz Shah Tughlaq | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1388–1413 | Ghiyath-ud-din Tughluq Shah / Abu Bakr Shah / Muhammad Shah / Mahmud Tughlaq / Nusrat Shah | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Medieval | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 1320 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1413[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Taka | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | India Nepal Pakistan Bangladesh | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Delhi Sultanate |

|---|

| Ruling dynasties |

The Tughlaq dynasty (also known as Tughluq or Tughluk dynasty; Template:Lang-fa) was the third dynasty to rule over the Delhi sultanate in medieval India.[8] Its reign started in 1320 in Delhi when Ghazi Malik assumed the throne under the title of Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq. The dynasty ended in 1413.[1][9]

The dynasty expanded its territorial reach through a military campaign led by Muhammad ibn Tughluq, and reached its zenith between 1330 and 1335. It ruled most of the Indian subcontinent for this brief period.[5][10]

Origin

Tughlaq dynasty was of Turko-Mongol[11] or Turkic[12] origins. The etymology of the word Tughlaq is not certain. The 16th-century writer Firishta claims that it is an Indian corruption of the Turkic term Qutlugh, but this is doubtful.[13][14] Literary, numismatic and epigraphic evidence makes it clear that Tughlaq was not an ancestral designation, but the personal name of the dynasty's founder Ghazi Malik. Historians use the designation Tughlaq to describe the entire dynasty as a matter of convenience, but to call it the Tughlaq dynasty is inaccurate, as none of the dynasty's kings used Tughlaq as a surname: only Ghiyath al-Din's son Muhammad bin Tughluq called himself the son of Tughlaq Shah ("bin Tughlaq").[13][15]

The ancestry of the dynasty is debated among modern historians because the earlier sources provide different information regarding it. Tughlaq's court poet Badr-i Chach attempted to find a royal Sassanian genealogy for the dynasty from the line of Bahram Gur, which seems to be the official position of the genealogy of the Sultan,[16] although this can be dismissed as flattery.[17]

Peter Jackson suggested that Tughlaq was of Mongol stock and a follower of the Mongol chief Alaghu.[18] The Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta states with reference to the Sufi saint Rukn-e-Alam that Tughluq belonged to the "Qarauna" [Neguderi] tribe of Turks, who lived in the hilly region between Turkestan and Sindh, and were in fact Mongols.[19]

Rise to power

) and the "King of Colombo" ruler of the city of Kollam (bottom, flag:

) and the "King of Colombo" ruler of the city of Kollam (bottom, flag:  , identified as Christian due to the early Saint Thomas Christianity there, and the Catholic mission under Jordanus since 1329), in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[20] The captions are informative,[21] and several of the location names are accurate.[22]

, identified as Christian due to the early Saint Thomas Christianity there, and the Catholic mission under Jordanus since 1329), in the contemporary Catalan Atlas of 1375.[20] The captions are informative,[21] and several of the location names are accurate.[22]The Khalji dynasty ruled the Delhi Sultanate before 1320.[23] Its last ruler, Khusro Khan, was a Hindu slave who had been forcibly converted to Islam and then served the Delhi Sultanate as the general of its army for some time.[24] Khusro Khan, along with Malik Kafur, had led numerous military campaigns on behalf of Alauddin Khalji, to expand the Sultanate and plunder non-Muslim kingdoms in India.[25][26]

After Alauddin Khalji's death from illness in 1316, a series of palace arrests and assassinations followed,[27] with Khusro Khan coming to power in June 1320, after killing the licentious son of Alauddin Khalji, Mubarak Khalji, initiating a massacre of all members of the Khalji family and reverting from Islam.[23] However, he lacked the support of the Muslim nobles and aristocrats of the Delhi Sultanate. Delhi's aristocracy invited Ghazi Malik, then the governor in Punjab under the Khaljis, to lead a coup in Delhi and remove Khusro Khan. In 1320, Ghazi Malik launched an attack with the use of an army of Khokhar tribesmen and killed Khusro Khan to assume power.[10][28]

Chronology

Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq

After assuming power, Ghazi Malik renamed himself Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq – thus starting and naming the Tughlaq dynasty.[29] He rewarded all those maliks, amirs and officials of Khalji dynasty who had rendered him a service and helped him come to power. He punished those who had rendered service to Khusro Khan, his predecessor. He lowered the tax rate on Muslims that was prevalent during Khalji dynasty, but raised the taxes on Hindus, wrote his court historian Ziauddin Barani, so that they might not be blinded by wealth or afford to become rebellious.[29] He built a city six kilometers east of Delhi, with a fort considered more defensible against the Mongol attacks, and called it Tughlakabad.[25]

In 1321, he sent his eldest son Jauna Khan, later known as Muhammad bin Tughlaq, to Deogir to plunder the Hindu kingdoms of Arangal and Tilang (now part of Telangana). His first attempt was a failure.[30] Four months later, Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq sent large army reinforcements for his son asking him to attempt plundering Arangal and Tilang again.[31] This time Jauna Khan succeeded. Arangal fell, was renamed to Sultanpur, and all plundered wealth, state treasury and captives were transferred from the captured kingdom to Delhi Sultanate.

The Muslim aristocracy in Lakhnauti (Bengal) invited Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq to extend his coup and expand eastwards into Bengal by attacking Shamsuddin Firoz Shah, which he did over 1324–1325 AD,[30] after placing Delhi under control of his son Ulugh Khan, and then leading his army to Lukhnauti. Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq succeeded in this campaign. As he and his favourite son Mahmud Khan were returning from Lukhnauti to Delhi, Jauna Khan schemed to kill him inside a wooden structure (kushk) built without foundation and designed to collapse, making it appear as an accident. Historic documents state that the Sufi preacher and Jauna Khan had learnt through messengers that Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq had resolved to remove them from Delhi upon his return.[33] Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, along with Mahmud Khan, died inside the collapsed kushk in 1325 AD, while his eldest son watched.[34] One official historian of Tughlaq court gives an alternate fleeting account of his death, as caused by a lightning bolt strike on the kushk.[35] Another official historian, Al-Badāʾunī ʻAbd al-Kadir ibn Mulūk-Shāh, makes no mention of lightning bolt or weather, but explains the cause of structural collapse to be the running of elephants; Al-Badaoni includes a note of the rumour that the accident was pre-planned.[30]

Patricide

According to many historians such as Ibn Battuta, al-Safadi, Isami,[5] and Vincent Smith,[36] Ghiyasuddin was killed by his eldest son Jauna Khan in 1325 AD. Jauna Khan ascended to power as Muhammad bin Tughlaq, and ruled for 26 years.[37]

Muhammad bin Tughluq

During Muhammad bin Tughluq's rule, Delhi Sultanate temporarily expanded to most of the Indian subcontinent, its peak in terms of geographical reach.[38] He attacked and plundered Malwa, Gujarat, Mahratta, Tilang, Kampila, Dhur-samundar, Mabar, Lakhnauti, Chittagong, Sunarganw and Tirhut.[39] His distant campaigns were expensive, although each raid and attack on non-Muslim kingdoms brought new looted wealth and ransom payments from captured people. The extended empire was difficult to retain, and rebellions all over Indian subcontinent became routine.[40]

He raised taxes to levels where people refused to pay any. In India's fertile lands between Ganges and Yamuna rivers, the Sultan increased the land tax rate on non-Muslims by tenfold in some districts, and twentyfold in others.[41] Along with land taxes, dhimmis (non-Muslims) were required to pay crop taxes by giving up half or more of their harvested crop. These sharply higher crop and land tax led entire villages of Hindu farmers to quit farming and escape into jungles; they refused to grow anything or work at all.[40] Many became robber clans.[41] Famines followed. The Sultan responded with bitterness by expanding arrests, torture and mass punishments, killing people as if he was "cutting down weeds".[40] Historical documents note that Muhammad bin Tughluq was cruel and severe not only with non-Muslims, but also with certain sects of Musalmans. He routinely executed Sayyids (Shia), Sufis, Qalandars, and other Muslim officials. His court historian Ziauddin Barni noted,

Not a day or week passed without spilling of much Musalman blood, (...)

— Ziauddin Barni, Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi[42]

Muhammad bin Tughlaq chose the city of Deogiri in present-day Indian state of Maharashtra (renaming it to Daulatabad), as the second administrative capital of the Dehli Sultanate.[43] He ordered a forced migration of the Muslim population of Dehli, including his royal family, the nobles, Syeds, Sheikhs and 'Ulema to settle in Daulatabad. The purpose of transferring the entire Muslim elite to Daulatabad was to enroll them in his mission of world conquest. He saw their role as propagandists who would adapt Islamic religious symbolism to the rhetoric of empire, and that the Sufis could by persuasion bring many of the inhabitants of the Deccan to become Muslim.[44] Tughluq cruelly punished the nobles who were unwilling to move to Daulatabad, seeing their non-compliance of his order as equivalent to rebellion. According to Ferishta, when the Mongols arrived in Punjab, the Sultan returned the elite back to Delhi, although Daulatabad remained as an administrative centre.[45] One result of the transfer of the elite to Daulatabad was the nobility's hatred of the Sultan, which remained in their minds for a long time.[46] The other result was that he managed to create a stable Muslim elite and result in the growth of the Muslim population of Daulatabad who did not return to Dehli,[38] without which the rise of the Bahmanid kingdom to challenge Vijayanagara would not have been possible.[47] These were a community of Urdu-speaking people of North Indian Muslims.[48] Muhammad bin Tughlaq's adventures in the Deccan region also marked campaigns of destruction and desecration of Hindu and Jain temples, for example the Swayambhu Shiva Temple and the Thousand Pillar Temple.[49]

Revolts against Muhammad bin Tughlaq began in 1327, continued over his reign, and over time the geographical reach of the Sultanate shrunk particularly after 1335. The Indian Muslim soldier Jalaluddin Ahsan Khan, a native of Kaithal in North India, founded the Madurai Sultanate in South India.[50][51][52] The Vijayanagara Empire originated in southern India as a direct response to attacks from the Delhi Sultanate.[53] The Vijayanagara Empire liberated southern India from the Delhi Sultanate.[54] In 1336 Kapaya Nayak of the Musunuri Nayak defeated the Tughlaq army and reconquered Warangal from the Delhi Sultanate.[55] In 1338 his own nephew rebelled in Malwa, whom he attacked, caught and flayed alive.[41] By 1339, the eastern regions under local Muslim governors and southern parts led by Hindu kings had revolted and declared independence from Delhi Sultanate. Muhammad bin Tughlaq did not have the resources or support to respond to the shrinking kingdom.[56] By 1347, the Deccan had revolted under Ismail Mukh, an Afghan.[57] Despite this, he was elderly and had no interest in ruling, and as a result, he stepped down in favor of Zafar Khan, another Afghan, who was the founder of the Bahmanid Sultanate.[58][59][60] As a result, the Deccan had become an independent and competing Muslim kingdom[61][62][63][64][65]

Muhammad bin Tughlaq was an intellectual, with extensive knowledge of Quran, Fiqh, poetry and other fields.[40] He was deeply suspicious of his kinsmen and wazirs (ministers), extremely severe with his opponents, and took decisions that caused economic upheaval. For example, after his expensive campaigns to expand Islamic empire, the state treasury was empty of precious metal coins. So he ordered minting of coins from base metals with face value of silver coins – a decision that failed because ordinary people minted counterfeit coins from base metal they had in their houses.[36][38]

Ziauddin Barni, a historian in Muhammad bin Tughlaq's court, wrote that the houses of Hindus became a coin mint and people in Hindustan provinces produced fake copper coins worth crores to pay the tribute, taxes and jizya imposed on them.[66] The economic experiments of Muhammad bin Tughlaq resulted in a collapsed economy, and nearly a decade long famine followed that killed numerous people in the countryside.[36] The historian Walford chronicled Delhi and most of India faced severe famines during Muhammad bin Tughlaq's rule, in the years after the base metal coin experiment.[67][68] Tughlaq introduced token coinage of brass and copper to augment the silver coinage which only led to increasing ease of forgery and loss to the treasury. Also, the people were not willing to trade their gold and silver for the new brass and copper coins.[69] Consequently, the sultan had to withdraw the lot, "buying back both the real and the counterfeit at great expense until mountains of coins had accumulated within the walls of Tughluqabad."[70]

Muhammad bin Tughlaq planned an attack on Khurasan and Irak (Babylon and Persia) as well as China to bring these regions under Sunni Islam.[71] For Khurasan attack, a cavalry of over 300,000 horses were gathered near Delhi, for a year at state treasury's expense, while spies claiming to be from Khurasan collected rewards for information on how to attack and subdue these lands. However, before he could begin the attack on Persian lands in the second year of preparations, the plunder he had collected from Indian subcontinent had emptied, provinces were too poor to support the large army, and the soldiers refused to remain in his service without pay. For the attack on China, Muhammad bin Tughlaq sent 100,000 soldiers, a part of his army, over the Himalayas.[41] However, Hindus closed the passes through the Himalayas and blocked the passage for retreat. Kangra's Prithvi Chand II defeated the army of Muhammad bin Tughluq which was not able to fight in the hills. Nearly all his 100,000 soldiers perished in 1333 and were forced to retreat.[72] The high mountain weather and lack of retreat destroyed that army in the Himalayas.[71] The few soldiers who returned with bad news were executed under orders of the Sultan.[73]

During his reign, state revenues collapsed from his policies. To cover state expenses, Muhammad bin Tughlaq sharply raised taxes on his ever-shrinking empire. Except in times of war, he did not pay his staff from his treasury. Ibn Battuta noted in his memoir that Muhammad bin Tughlaq paid his army, judges (qadi), court advisors, wazirs, governors, district officials and others in his service by awarding them the right to force collect taxes on Hindu villages, keep a portion and transfer rest to his treasury.[74][75] Those who failed to pay taxes were hunted and executed.[41] Muhammad bin Tughlaq died in March 1351[5] while trying to chase and punish people for rebellion and their refusal to pay taxes in Sindh (now in Pakistan) and Gujarat (now in India).[56]

Historians have attempted to determine the motivations behind Muhammad bin Tughlaq's behavior and his actions. Some[5] state Tughlaq tried to enforce orthodox Islamic observance and practice, promote jihad in South Asia as al-Mujahid fi sabilillah ('Warrior for the Path of God') under the influence of Ibn Taymiyyah of Syria. Others[76] suggest insanity.

At the time of Muhammad bin Tughlaq's death, the geographic control of Delhi Sultanate had shrunk to the north of the Narmada river.[5]

Feroz Shah Tughluq

After Muhammad bin Tughluq died, a collateral relative, Mahmud Ibn Muhammad, ruled for less than a month. Thereafter, Muhammad bin Tughluq's 45-year-old nephew Firuz Shah Tughlaq replaced him and assumed the throne. His rule lasted 37 years.[81] His father Sipah Rajab had become infatuated with a Hindu princess named Naila. She initially refused to marry him. Her father refused the marriage proposal as well. Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq and Sipah Rajab then sent in an army with a demand for one year taxes in advance and a threat of seizure of all property of her family and Abohar people. The kingdom was suffering from famines, and could not meet the ransom demand. The princess, after learning about ransom demands against her family and people, offered herself in sacrifice if the army would stop the misery to her people. Sipah Rajab and the Sultan accepted the proposal. Sipah Rajab and Naila were married and Firoz Shah was their first son.[82]

The court historian Ziauddin Barni, who served both Muhammad Tughlaq and the first six years of Firoz Shah Tughlaq, noted that all those who were in service of Muhammad were dismissed and executed by Firoz Shah. In his second book, Barni states that Firuz Shah was the mildest sovereign since the rule of Islam came to Delhi. Muslim soldiers enjoyed the taxes they collected from Hindu villages they had rights over, without having to constantly go to war as in previous regimes.[5] Other court historians such as 'Afif record a number of conspiracies and assassination attempts on Firoz Shah Tughlaq, such as by his first cousin and the daughter of Muhammad bin Tughlaq.[83]

Firoz Shah Tughlaq tried to regain the old kingdom boundary by waging a war with Bengal for 11 months in 1359. However, Bengal did not fall, and remained outside of Delhi Sultanate. Firuz Shah Tughlaq was somewhat weak militarily, mainly because of inept leadership in the army.[81]

An educated sultan, Firoz Shah left a memoir.[84] In it he wrote that he banned torture in practice in Delhi Sultanate by his predecessors, tortures such as amputations, tearing out of eyes, sawing people alive, crushing people's bones as punishment, pouring molten lead into throats, putting people on fire, driving nails into hands and feet, among others.[85] The Sunni Sultan also wrote that he did not tolerate attempts by Rafawiz Shia Muslim and Mahdi sects from proselytizing people into their faith, nor did he tolerate Hindus who tried to rebuild their temples after his armies had destroyed those temples.[86] As punishment, wrote the Sultan, he put many Shias, Mahdi and Hindus to death (siyasat). Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, his court historian, also recorded Firoz Shah Tughlaq burning a Hindu Brahmin alive for converting Muslim women to infidelity.[87] In his memoirs, Firoz Shah Tughlaq lists his accomplishments to include converting Hindus to Sunni Islam by announcing an exemption from taxes and jizya for those who convert, and by lavishing new converts with presents and honours. Simultaneously, he raised taxes and jizya, assessing it at three levels, and stopping the practice of his predecessors who had historically exempted all Hindu Brahmins from jizya tax.[85][88] He also vastly expanded the number of slaves in his service and those of amirs (Muslim nobles). Firoz Shah Tughlaq reign was marked by reduction in extreme forms of torture, eliminating favours to select parts of society, but an increased intolerance and persecution of targeted groups.[85] After the death of his heir in 1376 AD, Firuz Shah started strict implementation of Sharia throughout his dominions.[5]

Firuz Shah suffered from bodily infirmities, and his rule was considered by his court historians as more merciful than that of Muhammad bin Tughlaq.[89] When Firuz Shah came to power, India was suffering from a collapsed economy, abandoned villages and towns, and frequent famines. He undertook many infrastructure projects including an irrigation canal connecting Yamuna-Ghaggar and Yamuna-Sutlej rivers, bridges, madrasas (religious schools), mosques and other Islamic buildings.[5] Firuz Shah Tughlaq is credited with patronizing Indo-Islamic architecture, including the installation of lats (ancient Hindu and Buddhist pillars) near mosques. The irrigation canals continued to be in use through the 19th century.[89] After Feroz died in 1388, the Tughlaq dynasty's power continued to fade, and no more able leaders came to the throne. Firoz Shah Tughlaq's death created anarchy and disintegration of kingdom. In the years preceding his death, internecine strife among his descendants had already erupted.[5]

Civil wars

The first civil war broke out in 1384 AD four years before the death of aging Firoz Shah Tughlaq, while the second civil war started in 1394 AD six years after Firoz Shah was dead.[90] The Islamic historians Sirhindi and Bihamadkhani provide the detailed account of this period. These civil wars were primarily between different factions of Sunni Islam aristocracy, each seeking sovereignty and land to tax dhimmis and extract income from resident peasants.[91]

Firuz Shah Tughluq's favorite grandson died in 1376. Thereafter, Firuz Shah sought and followed Sharia more than ever, with the help of his wazirs. He himself fell ill in 1384. By then, Muslim nobility who had installed Firuz Shah Tughluq to power in 1351 had died out, and their descendants had inherited the wealth and rights to extract taxes from non-Muslim peasants. Khan Jahan II, a wazir in Delhi, was the son of Firuz Shah Tughluq's favorite wazir Khan Jahan I, and rose in power after his father died in 1368 AD.[93] The young wazir was in open rivalry with Muhammad Shah, the son of Firuz Shah Tughluq.[94] The wazir's power grew as he appointed more amirs and granted favors. He persuaded the Sultan to name his great-grandson as his heir. Then Khan Jahan II tried to convince Firuz Shah Tughlaq to dismiss his only surviving son. Instead of dismissing his son, the Sultan dismissed the wazir. The crisis that followed led to first civil war, arrest and execution of the wazir, followed by a rebellion and civil war in and around Delhi. Muhammad Shah too was expelled in 1387 AD. The Sultan Firuz Shah Tughluq died in 1388 AD. Tughluq Khan assumed power, but died in conflict. In 1389, Abu Bakr Shah assumed power, but he too died within a year. The civil war continued under Sultan Muhammad Shah, and by 1390 AD, it had led to the seizure and execution of all Muslim nobility who were aligned, or suspected to be aligned to Khan Jahan II.[94]

While the civil war was in progress, predominantly Hindu populations of Himalayan foothills of north India had rebelled, stopped paying Jizya and Kharaj taxes to Sultan's officials. Hindus of southern Doab region of India (now Etawah) joined the rebellion in 1390 AD. Sultan Muhammad Shah attacked Hindus rebelling near Delhi and southern Doab in 1392, with mass executions of peasants, and razing Etawah to the ground.[94][95] However, by then, most of India had transitioned to a patchwork of smaller Muslim Sultanates and Hindu kingdoms. In 1394, Hindus in Lahore region and northwest South Asia (now Pakistan) had re-asserted self-rule. Muhammad Shah amassed an army to attack them, with his son Humayun Khan as the commander-in-chief. While preparations were in progress in Delhi in January 1394, Sultan Muhammad Shah died. His son, Humayun Khan assumed power but was murdered within two months. The brother of Humayun Khan, Nasir-al-din Mahmud Shah assumed power – but he enjoyed little support from Muslim nobility, the wazirs and amirs.[94] The Sultanate had lost command over almost all eastern and western provinces of already shrunken Sultanate. Within Delhi, factions of Muslim nobility formed by October 1394 AD, triggering the second civil war.[94]

Tartar Khan installed a second Sultan, Nasir-al-din Nusrat Shah in Firozabad, few kilometers from the first Sultan seat of power in late 1394. The two Sultans claimed to be rightful ruler of South Asia, each with a small army, controlled by a coterie of Muslim nobility.[94] Battles occurred every month, duplicity and switching of sides by amirs became commonplace, and the civil war between the two Sultan factions continued through 1398, till the invasion by Timur.[95]

Timur's Invasion

The lowest point for the dynasty came in 1398, when Turco-Mongol[96][97] invader, Timur (Tamerlane) defeated four armies of the Sultanate. During the invasion, Sultan Mahmud Khan fled before Tamerlane as he entered Delhi. For eight days Delhi was plundered, its population massacred, and over 100,000 prisoners were killed as well.[98]

The capture of the Delhi Sultanate was one of Timur's greatest victories, as at that time, Delhi was one of the richest cities in the world. After Delhi fell to Timur's army, uprisings by its citizens against the Turkic-Mongols began to occur, causing a retaliatory bloody massacre within the city walls. After three days of citizens uprising within Delhi, it was said that the city reeked of the decomposing bodies of its citizens with their heads being erected like structures and the bodies left as food for the birds by Timur's soldiers. Timur's invasion and destruction of Delhi continued the chaos that was still consuming India, and the city would not be able to recover from the great loss it suffered for almost a century.[99][100]: 269–274

It is believed that before his departure, Timur appointed Khizr Khan, the future founder of the succeeding Sayyid dynasty, as his viceroy at Delhi. Initially, Khizr Khan could only establish his control over Multan, Dipalpur and parts of Sindh. Soon he started his campaign against the Tughlaq dynasty, and entered Delhi victoriously on 6 June 1414.[101]

Ibn Battuta's memoir on Tughlaq dynasty

Ibn Battuta, the Moroccan Muslim traveller, left extensive notes on Tughlaq dynasty in his travel memoirs. Ibn Battuta arrived in India through the mountains of Afghanistan, in 1334, at the height of Tughlaq dynasty's geographic empire.[75] On his way, he learnt that Sultan Muhammad Tughluq liked gifts from his visitors, and gave to his visitors gifts of far greater value in return. Ibn Battuta met Muhammad bin Tughluq, presenting him with gifts of arrows, camels, thirty horses, slaves and other goods. Muhammad bin Tughlaq responded by giving Ibn Battuta with a welcoming gift of 2,000 silver dinars, a furnished house and the job of a judge with an annual salary of 5,000 silver dinars that Ibn Battuta had the right to keep by collecting taxes from two and a half Hindu villages near Delhi.[74]

In his memoirs about Tughlaq dynasty, Ibn Batutta recorded the history of Qutb complex which included Quwat al-Islam Mosque and the Qutb Minar.[102] He noted the seven-year famine from 1335 AD, which killed thousands upon thousands of people near Delhi, while the Sultan was busy attacking rebellions.[74] He was tough both against non-Muslims and Muslims. For example,

Not a week passed without the spilling of much Muslim blood and the running of streams of gore before the entrance of his palace. This included cutting people in half, skinning them alive, chopping off heads and displaying them on poles as a warning to others, or having prisoners tossed about by elephants with swords attached to their tusks.

— Ibn Battuta, Travel Memoirs (1334-1341, Delhi)[74]

The Sultan was far too ready to shed blood. He punished small faults and great, without respect of persons, whether men of learning, piety or high station. Every day hundreds of people, chained, pinioned, and fettered, are brought to this hall, and those who are for execution are executed, for torture tortured, and those for beating beaten.

— Ibn Battuta, Chapter XV Rihla (Delhi)[104]

In Tughlaq dynasty, the punishments were extended even to Muslim religious figures who were suspected rebellion.[102] For example, Ibn Battuta mentions Sheikh Shinab al-Din, who was imprisoned and tortured as follows:

On the fourteen day, the Sultan sent him food, but he (Sheikh Shinab al-Din) refused to eat it. When the Sultan heard this he ordered that the sheikh should be fed human excrement [dissolved in water]. [His officials] spread out the sheikh on his back, opened his mouth and made him drink it (the excrement). On the following day, he was beheaded.

Ibn Batutta wrote that Sultan's officials demanded bribes from him while he was in Delhi, as well as deducted 10% of any sums that Sultan gave to him.[106] Towards the end of his stay in Tughluq dynasty court, Ibn Battuta came under suspicion for his friendship with a Sufi Muslim holy man.[75] Both Ibn Battuta and the Sufi Muslim were arrested. While Ibn Battuta was allowed to leave India, the Sufi Muslim was killed as follows according to Ibn Battuta during the period he was under arrest:

(The Sultan) had the holy man's beard plucked out hair by hair, then banished him from Delhi. Later the Sultan ordered him to return to court, which the holy man refused to do. The man was arrested, tortured in the most horrible way, then beheaded.

— Ibn Battuta, Travel Memoirs (1334-1341, Delhi)[75]

Slavery under Tughlaq dynasty

Each military campaign and raid on non-Muslim kingdoms yielded loot and seizure of slaves. Additionally, the Sultans patronized a market (al-nakhkhās[107]) for trade of both foreign and Indian slaves.[108] This market flourished under the reign of all Sultans of Tughlaq dynasty, particularly Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq, Muhammad Tughlaq and Firoz Tughlaq.[109]

Ibn Battuta's memoir records that he fathered a child each with two slave girls, one from Greece and one he purchased during his stay in Delhi Sultanate. This was in addition to the daughter he fathered by marrying a Muslim woman in India.[110] Ibn Battuta also records that Muhammad Tughlaq sent along with his emissaries, both slave boys and slave girls as gifts to other countries such as China.[111]

Muslim nobility and revolts

The Tughlaq dynasty experienced many revolts by Muslim nobility, particularly during Muhammad bin Tughlaq's reign but also during rule of later monarchs such as Firoz Shah Tughlaq.[81][112]

The Tughlaqs had attempted to manage their expanded empire by appointing family members and Muslim aristocracy as na'ib (نائب) of Iqta' (farming provinces, اقطاع) under contract.[81] The contract would require that the na'ib shall have the right to forcefully collect taxes from non-Muslim peasants and local economy, and deposit a fixed sum of tribute and taxes to Sultan's treasury on a periodic basis.[81][114] The contract allowed the na'ib to keep a certain amount of taxes they collected from peasants as their income, but the contract required any excess tax and seized property collected from non-Muslims to be split between na'ib and Sultan in a 20:80 ratio. (Firuz Shah changed this to 80:20 ratio.) The na'ib had the right to keep soldiers and officials to help extract taxes. After contracting with Sultan, the na'ib would enter into subcontracts with Muslim amirs and army commanders, each granted the right over certain villages to force collect or seize produce and property from dhimmis.[114]

This system of tax extraction from peasants and sharing among Muslim nobility led to rampant corruption, arrests, execution and rebellion. For example, in the reign of Firoz Shah Tughlaq, a Muslim noble named Shamsaldin Damghani entered into a contract over the iqta' of Gujarat, promising enormous sums of annual tribute while entering the contract in 1377 AD.[81] He then attempted to force collect the amount deploying his coterie of Muslim amirs, but failed. Even the amount he did manage to collect, he paid nothing to Delhi.[114] Shamsaldin Damghani and Muslim nobility of Gujarat then declared rebellion and separation from Delhi Sultanate. However, the soldiers and peasants of Gujarat refused to fight the war for the Muslim nobility. Shamsaldin Damghani was killed.[81] During the reign of Muhammad Shah Tughlaq, similar rebellions were very common. His own nephew rebelled in Malwa in 1338 AD; Muhammad Shah Tughlaq attacked Malwa, seized his nephew, and then flayed him alive in public.[41]

Downfall

The provinces of Deccan, Bengal, Sindh and Multhan had become independent during the reign of Muhammad bin Tughlaq. The invasion of Timur further weakened the Tughlaq empire and allowed several regional chiefs to become independent, resulting in the formation of the sultanates of Gujarat, Malwa and Jaunpur. The Rajput states also expelled the governor of Ajmer and asserted control over Rajputana. The Tughlaq power continued to decline until they were finally overthrown by their former governor of Multhan, Khizr Khan, resulting in the rise of the Sayyid Dynasty as the new rulers of the Delhi Sultanate.[115]

Indo-Islamic Architecture

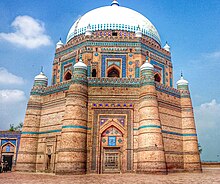

The Sultans of Tughlaq dynasty, particularly Firoz Shah Tughlaq, patronized many construction projects and are credited with the development of Indo-Islamic architecture.[116]

-

Tughlaqabad Fort, Tughlaqabad, Delhi.

-

Sultan Ghiyath-ud-din Tughluq Shah's Mausoleum in Tughlaqabad Fort, Tughlaqabad, Delhi.

-

Tughlaqabad fort wall

-

Tughlaqabad Fort

-

Sultan Feroze Shah Tughlaq's tomb with adjoining Madrassa, in Hauz Khas Complex, Delhi.

-

Feroze Shah Kotla ruins, painted in 1802.

-

West Gate of Firozabad (present Feroz Shah Kotla), painted in 1802.

-

Feroz Shah Kotla remains next to the Feroz Shah Kotla Cricket Stadium.

Rulers

| Titular Name | Personal Name[citation needed] | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| Sultan Ghiyath-ud-din Tughluq Shah سلطان غیاث الدین تغلق شاہ |

Ghazi Malik غازی ملک |

1320–1325 |

| Sultan Muhammad Adil bin Tughluq Shah سلطان محمد عادل بن تغلق شاہ Ulugh Khan الغ خان Juna Khan جنا خان |

Malik Fakhr-ud-din Jauna ملک فخر الدین |

1325–1351 |

| Sultan Feroze Shah Tughluq سلطان فیروز شاہ تغلق |

Malik Feroze ibn Malik Rajab ملک فیروز ابن ملک رجب |

1351–1388 |

| Sultan Ghiyath-ud-din Tughluq Shah سلطان غیاث الدین تغلق شاہ |

Tughluq Khan ibn Fateh Khan ibn Feroze Shah تغلق خان ابن فتح خان ابن فیروز شاہ |

1388–1389 |

| Sultan Abu Bakr Shah سلطان ابو بکر شاہ |

Abu Bakr Khan ibn Zafar Khan ibn Fateh Khan ibn Feroze Shah ابو بکر خان ابن ظفر خان ابن فتح خان ابن فیروز شاہ |

1389–1390 |

| Sultan Muhammad Shah سلطان محمد شاہ |

Muhammad Shah ibn Feroze Shah محمد شاہ ابن فیروز شاہ |

1390–1394 |

| Sultan Ala-ud-din Sikandar Shah سلطان علاءالدین سکندر شاہ |

Humayun Khan ھمایوں خان |

1394 |

| Sultan Nasir-ud-din Mahmud Shah Tughluq سلطان ناصر الدین محمود شاہ تغلق |

Mahmud Shah ibn Muhammad Shah محمود شاہ ابن محمد شاہ |

1394–1412/1413 |

| Sultan Nasir-ud-din Nusrat Shah Tughluq سلطان ناصر الدین نصرت شاہ تغلق |

Nusrat Khan ibn Fateh Khan ibn Feroze Shah نصرت خان ابن فتح خان ابن فیروز شاہ |

1394–1398 |

- The coloured rows signify the splitting of Delhi Sultanate under two Sultans; one in the east (Orange) at Firozabad & the other in the west (Yellow) at Delhi.

See also

| History of the Turkic peoples pre–14th century |

|---|

|

References

- ^ a b Edmund Wright (2006), A Dictionary of World History, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780192807007

- ^ Grey flag with black vertical stripe according to the Catalan Atlas of c. 1375:

in the depiction of the Delhi Sultanate in the Catalan Atlas

in the depiction of the Delhi Sultanate in the Catalan Atlas

- ^ Kadoi, Yuka (2010). "On the Timurid flag". Beiträge zur islamischen Kunst und Archäologie. 2: 148.

...helps identify another curious flag found in northern India – a brown or originally sliver flag with a vertical black line – as the flag of the Delhi Sultanate (602-962/1206-1555).

- ^ Note: other sources describe the use of two flags: the black Abbasid flag, and the red Ghurid flag, as well as various banners with figures of the new moon, a dragon or a lion. "Large banners were carried with the army. In the beginning the sultans had only two colours : on the right were black flags, of Abbasid colour; and on the left they carried their own colour, red, which was derived from Ghor. Qutb-u'd-din Aibak's standards bore the figures of the new moon, a dragon or a lion; Firuz Shah's flags also displayed a dragon." in Qurashi, Ishtiyaq Hussian (1942). The Administration of the Sultanate of Delhi. Kashmiri Bazar Lahore: SH. MUHAMMAD ASHRAF. p. 143. , also in Jha, Sadan (8 January 2016). Reverence, Resistance and Politics of Seeing the Indian National Flag. Cambridge University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-107-11887-4., also "On the right of the Sultan was carried the black standard of the Abbasids and on the left the red standard of Ghor." in Thapliyal, Uma Prasad (1938). The Dhvaja, Standards and Flags of India: A Study. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 94. ISBN 978-81-7018-092-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Jackson, Peter (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521543293.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (j). ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ "Arabic and Persian Epigraphical Studies - Archaeological Survey of India". Asi.nic.in. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ Lombok, E.J. Brill's First Encyclopedia of Islam, Vol 5, ISBN 90-04-09796-1, pp 30, 129-130

- ^ Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. pp. 90–102. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- ^ a b W. Haig (1958), The Cambridge History of India: Turks and Afghans, Volume 3, Cambridge University Press, pp 153-163

- ^ ÇAĞMAN, FİLİZ; TANINDI, ZEREN (2011). "Selections from Jalayirid Books in the Libraries of Istanbul" (PDF). Muqarnas. 28: 231. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 23350289.

Muhammad Tughluq and his successors were contemporaries of the Jalayirid sultans; both dynasties were Turco-Mongol

- ^ Jamal Malik (2008). Islam in South Asia: A Short History. Brill Publishers. p. 104. ISBN 978-9004168596.

The founder of this new Turkish dynasty...

- ^ a b Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, p. 460.

- ^ An Advanced History of Muslim Rule in Indo-Pakistan. the University of Michigan. 1967. p. 94.

- ^ Aniruddha Ray (2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526)Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. ISBN 9781000007299.

- ^ Khalid Ahmad Nizami (1997). History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume 06, the Delhi Sultanate. Royalty in Medieval India. Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 9788121507332.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, p. 461.

- ^ Surender Singh (30 September 2019). The Making of Medieval Panjab: Politics, Society and Culture c. 1000–c. 1500. Routledge. ISBN 9781000760682.

- ^ Banarsi Prasad Saksena 1970, pp. 460, 461.

- ^ Massing, Jean Michel; Albuquerque, Luís de; Brown, Jonathan; González, J. J. Martín (1 January 1991). Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05167-4.

- ^ The caption for the Sultan of Delhi reads: Here is a great sultan, powerful and very rich: the sultan has seven hundred elephants and a hundred thousand horsemen under his command. He also has countless foot soldiers. In this part of the land there is a lot of gold and precious stones.

The caption for the southern king reads:

Here rules the king of Colombo, a Christian.

He was mistakenly identified as Christian because of the Christian mission established in Kollam since 1329.

In Liščák, Vladimír (2017). "Mapa mondi (Catalan Atlas of 1375), Majorcan cartographic school, and 14th century Asia" (PDF). International Cartographic Association: 5. - ^ Cartography between Christian Europe and the Arabic-Islamic World, 1100-1500: Divergent Traditions. BRILL. 17 June 2021. pp. 176–178. ISBN 978-90-04-44603-8.

- ^ a b Holt et al. (1977), The Cambridge History of Islam, Vol 2, ISBN 978-0521291378, pp 11-15

- ^ Vincent Smith, The Oxford Student's History of India at Google Books, Oxford University Press, pp 81-82

- ^ a b c William Hunter (1903), A Brief History of the Indian Peoples, p. 123, at Google Books, Frowde - Publisher to the Oxford University, London, 23rd Edition, pages 123-124

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-I Alai Amir Khusru, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 67-92; Quote - "The Rai again escaped him, and he ordered a general massacre at Kandur. He heard that in Brahmastpuri there was a golden idol. (He found it). He then determined on razing the beautiful temple to the ground. The roof was covered with rubies and emeralds, in short, it was the holy place of the Hindus, which Malik dug up from its foundations with the greatest care, while heads of idolaters fell to the ground and blood flowed in torrents. The Musulmans destroyed all the lings (idols). Many gold and valuable jewels fell into the hands of the Musulmans who returned to the royal canopy in April 1311 AD. Malik Kafur and the Musulmans destroyed all the temples at Birdhul, and placed in the plunder in the public treasury."

- ^ Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 214-218

- ^ Mohammad Arshad (1967), An Advanced History of Muslim Rule in Indo-Pakistan, OCLC 297321674, pp 90-92

- ^ a b Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 229-231

- ^ a b c William Lowe (Translator), Muntakhabu-t-tawārīkh, p. 296, at Google Books, Volume 1, pages 296-301

- ^ Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 233-234

- ^ ÇAĞMAN, FİLİZ; TANINDI, ZEREN (2011). "Selections from Jalayirid Books in the Libraries of Istanbul" (PDF). Muqarnas. 28: 230, 258 Fig.56. ISSN 0732-2992. JSTOR 23350289.

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Travels of Ibn Battuta Ibn Battuta, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 609-611

- ^ Henry Sharp (1938), DELHI: A STORY IN STONE, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Vol. 86, No. 4448, pp 324-325

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Táríkh-i Fíroz Sháh Ziauddin Barani, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 609-611

- ^ a b c Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp 236-242, Oxford University Press

- ^ Elliot and Dowson, Táríkh-i Fíroz Sháhí of Ziauddin Barani, The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period (Vol 3), London, Trübner & Co

- ^ a b c Muḥammad ibn Tughluq Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 236–237

- ^ a b c d Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 235–240

- ^ a b c d e f William Hunter (1903), A Brief History of the Indian Peoples, p. 124, at Google Books, 23rd Edition, pp. 124-127

- ^ Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 236–238

- ^ Aniruddha Ray (4 March 2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526): Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 9781000007299.

The Sultan created Daulatabad as the second administrative centre. A contemporary writer has written that the Empire had two capitals - Delhi and Daulatabad.

- ^ Carl W. Ernst (1992). Eternal Garden: Mysticism, History, and Politics at a South Asian Sufi Center. SUNY Press. ISBN 9781438402123.

- ^ Aniruddha Ray (4 March 2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526): Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. Routledge. ISBN 9781000007299.

- ^ Aniruddha Ray (4 March 2019). The Sultanate of Delhi (1206-1526): Polity, Economy, Society and Culture. ISBN 9781000007299.

The primary result of the transfer of the capital to Daulatabad was the hatred of the people towards the Sultan.

- ^ P.M. Holt; Ann K.S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis (22 May 1977). The Cambridge History of Islam" Volume 2A. Camgridge University Press. p. 15.

- ^ Kousar.J. Azam (2017). Languages and Literary Cultures in Hyderabad. Taylor & Francis. p. 8.

- ^ Richard Eaton, Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India at Google Books, (2004)

- ^ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Medieval India. p. 82. ISBN 9788171416837.

- ^ Kate Fleet, Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Devin J. Stewart. "Jalal al-Din Ahsan".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ M. S. Nagaraja Rao (1987). Kusumāñjali:New Interpretation of Indian Art & Culture : Sh. C. Sivaramamurti Commemoration Volume · Volume 2.

- ^ Hermann Kulke and Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, (Routledge, 1986), 188.

- ^ Advanced Study in the History of Medieval India by Jl Mehta p. 97

- ^ A Social History of the Deccan, 1300-1761: Eight Indian Lives, by Richard M. Eaton p.50

- ^ a b Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp. 242–248, Oxford University Press

- ^ Ahmed Farooqui, Salma (2011). Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century. Pearson. p. 150. ISBN 9789332500983.

- ^ Architecture and art of the Deccan sultanates (Vol 7 ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1999. p. 7. ISBN 9780521563215.

- ^ Wink, André (2020). The Making of the Indo-Islamic World C.700-1800 CE. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781108417747.

- ^ Government Gazette The United Provinces of Agra and Oudh (Part 2 ed.). Harvard University. 1910. p. 314.

- ^ See:

- M. Reza Pirbha, Reconsidering Islam in a South Asian Context, ISBN 978-9004177581, Brill

- Richards J. F. (1974), The Islamic frontier in the east: Expansion into South Asia, Journal of South Asian Studies, 4(1), pp. 91–109

- ^ McCann, Michael W. (15 July 1994). Rights at Work: Pay Equity Reform and the Politics of Legal Mobilization. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-55571-3.

- ^ Suvorova (2000). Masnavi. p. 3.

- ^ Husaini (Saiyid.), Abdul Qadir (1960). Bahman Shāh, the Founder of the Bahmani Kingdom. Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. pp. 59–60.

- ^ Jayanta Gaḍakarī (2000). Hindu Muslim Communalism, a Panchnama. p. 140.

- ^ Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pages 239-242

- ^ Cornelius Walford (1878), The Famines of the World: Past and Present, p. 3, at Google Books, pp. 9–10

- ^ Judith Walsh, A Brief History of India, ISBN 978-0816083626, pp. 70–72; Quote: "In 1335-42, during a severe famine and death in the Delhi region, the Sultanate offered no help to the starving residents."

- ^ Domenic Marbaniang, "The Corrosion of Gold in Light of Modern Christian Economics", Journal of Contemporary Christian, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Bangalore: CFCC), August 2013, p. 66

- ^ John Keay, India: A History (New Delhi: Harper Perennial, 2000), p. 269

- ^ a b Tarikh-I Firoz Shahi Ziauddin Barni, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 241–243

- ^ Chandra, Satish (1997). Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals. New Delhi, India: Har-Anand Publications. pp. 101–102. ISBN 978-8124105221.

- ^ Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, Oxford University Press, Chapter 2, pp. 236–242

- ^ a b c d Ross Dunn (1989), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century, University of California Press, Berkeley, Excerpts Archived 24 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Ibn Battuta's Trip: Chapter 7 - Delhi, capital of Muslim India Archived 24 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine Travels of Ibn Battuta: 1334-1341, University of California, Berkeley

- ^ George Roy Badenoc (1901), The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record, p. 13, at Google Books, 3rd Series, Volume 9, Nos. 21-22, pp. 13–15

- ^ McKibben, William Jeffrey (1994). "The Monumental Pillars of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq". Ars Orientalis. 24: 105–118. JSTOR 4629462.

- ^ HM Elliot & John Dawson (1871), Tarikh I Firozi Shahi - Records of Court Historian Sams-i-Siraj The History of India as told by its own historians, Volume 3, Cornell University Archives, pp 352-353

- ^ Prinsep, J (1837). "Interpretation of the most ancient of inscriptions on the pillar called lat of Feroz Shah, near Delhi, and of the Allahabad, Radhia and Mattiah pillar, or lat inscriptions which agree therewith". Journal of the Asiatic Society. 6 (2): 600–609.

- ^ Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India no.52. 1937. p. Plate II.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jackson, Peter (1999). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 296–309. ISBN 978-0-521-40477-8.

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 271–273

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 290–292

- ^ Firoz Shah Tughlak, Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi - Memoirs of Firoz Shah Tughlak, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 3 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives

- ^ a b c Vincent A Smith, The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, p. 217, at Google Books, Chapter 2, pp. 249–251, Oxford University Press

- ^ Firoz Shah Tughlak, Futuhat-i Firoz Shahi - Autobiographical memoirs, Translated in 1871 by Elliot and Dawson, Volume 3 - The History of India, Cornell University Archives, pp. 377–381

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 365–366

- ^ Annemarie Schimmel, Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, ISBN 978-9004061170, Brill Academic, pp 20-23

- ^ a b William Hunter (1903), A Brief History of the Indian Peoples, p. 126, at Google Books, Frowde - Publisher to the Oxford University, London, 23rd Edition, pp. 126–127

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1999). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–310. ISBN 978-0-521-40477-8.

- ^ Agha Mahdi Husain (1963), Tughluq Dynasty, Thacker Spink, Calcutta

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 39, 147. ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 367–371

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, Peter (2003). The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 305–311. ISBN 978-0521543293.

- ^ a b Bihamadkhani, Muhammad (date unclear, estim. early 15th century) Ta'rikh-i Muhammadi, Translator: Muhammad Zaki, Aligarh Muslim University

- ^ B.F. Manz, The rise and rule of Timur, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1989, p. 28: "... We know definitely that the leading clan of the Barlas tribe traced its origin to Qarchar Barlas, head of one of Chaghadai's regiments ... These then were the most prominent members of the Ulus Chaghadai: the old Mongolian tribes - Barlas, Arlat, Soldus and Jalayir ..."

- ^ M.S. Asimov & C. E. Bosworth, History of Civilizations of Central Asia, UNESCO Regional Office, 1998, ISBN 92-3-103467-7, p. 320: "… One of his followers was […] Timur of the Barlas tribe. This Mongol tribe had settled […] in the valley of Kashka Darya, intermingling with the Turkish population, adopting their religion (Islam) and gradually giving up its own nomadic ways, like a number of other Mongol tribes in Transoxania …"

- ^ Hunter, Sir William Wilson (1909). "The Indian Empire: Timur's invasion 1398". The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Vol. 2. p. 366.

- ^ Marozzi, Justin (2004). Tamerlane: Sword of Islam, conqueror of the world. HarperCollins.

- ^ Josef W. Meri (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization. Routledge. p. 812. ISBN 9780415966900.

- ^ Majumdar, R.C. (ed.) (2006). The Delhi Sultanate, Mumbai: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, pp. 125–8

- ^ a b c H. Gibb (1956), The Travels of Ibn Battuta, Vols. I, II, III, Hakluyt Society, Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 693–709

- ^ Anderson, Jennifer Cochran; Dow, Douglas N. (22 March 2021). Visualizing the Past in Italian Renaissance Art: Essays in Honor of Brian A. Curran. BRILL. p. 125. ISBN 978-90-04-44777-6.

detail of elephant near Delhi

- ^ Ibn Batutta, Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354, Translated by H Gibb, Routledge, ISBN 9780415344739, p. 203

- ^ "The Travels of Ibn Battuta". Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- ^ Ibn Batutta, Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354, Translated by H Gibb, Routledge, ISBN 9780415344739, pp. 208–209

- ^ "nak̲h̲k̲h̲ās", Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition, Editors: P.J. Bearmanet al, Brill, The Netherlands

- ^ I.H. Siddiqui (2012), Recording the Progress of Indian History: Symposia Papers of the Indian History Congress, Saiyid Jafri (Editor), ISBN 978-9380607283, pp. 443–448

- ^ Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 340–341

- ^ Insights into Ibn Battuta's Ideas of Women and Sexuality Archived 13 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine The Travels of Ibn Battuta, University of California, Berkeley

- ^ Samuel Lee (translator), Ibn Battuta - The Travels of Ibn Battuta: in the Near East, Asia and Africa, 2010, ISBN 978-1616402624, pp. 151–155

- ^ James Brown (1949), The History of Islam in India, The Muslim World, Volume 39, Issue 1, pp. 11–25

- ^ Bloom, Jonathan (1995). The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300064650. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Elliot and Dowson (Translators), Tarikh-i Firoz Shahi Shams-i Siraj 'Afif, The History of India by its own Historians - The Muhammadan Period, Volume 3, Trubner London, pp. 287–373

- ^ Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanate (1206–1526) By Satish Chandra p. 210 [1]

- ^ William McKibben (1994), The Monumental Pillars of Fīrūz Shāh Tughluq. Ars orientalis, Vol. 24, pp. 105–118

Bibliography

- Banarsi Prasad Saksena (1970). "The Tughluqs: Sultan Ghiyasuddin Tughluq". In Mohammad Habib and Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (ed.). A Comprehensive History of India: The Delhi Sultanat (A.D. 1206–1526). Vol. 5. The Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. OCLC 31870180.