Pre-Cabraline history of Brazil

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

The pre-Cabraline history of Brazil is the stage in Brazil's history before the arrival of Portuguese navigator Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500,[1] at a time when the region that is now Brazilian territory was occupied by thousands of indigenous peoples.

Traditional prehistory is generally divided into the Paleolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic periods. However, in Brazil, some authors prefer to work with the geological epochs of the current Quaternary period: Pleistocene and Holocene.[2] In this sense, the most accepted periodization is divided into: Pleistocene (hunters and gatherers at least 12,000 years ago) and Holocene, the latter being subdivided into Early Archaic (between 12,000 and 9,000 years ago), Middle Archaic (between 9,000 and 4,500 years ago) and Recent Archaic (from 4,000 years ago until the arrival of the Europeans). It is believed that the first peoples began to inhabit the region where Brazil is now located 60,000 years ago.[2]

The expression "prehistory of Brazil" is also used to refer to this period, but the term has been criticized since the concept of prehistory is questioned by some scholars as being a Eurocentric worldview, in which people without writing would be people without history. In the context of Brazilian history, this nomenclature would not accept that the indigenous people had their own history.[1] For this reason, some prefer to call this period pre-Cabraline.[3]

Study methodology

The study of Brazilian history before 1500 is mostly done through archaeology, since the peoples who occupied the territory are not known to have writing systems.[1][4] Linguistic, ethnological, and historical studies have aided archaeological research as much as possible. However, few authors have attempted to reconstruct this history in a panoramic way (and attempts by archaeologists to establish an overview of pre-Cabraline history have not proved satisfactory).[1] A further aggravating factor is that much remains to be done at various levels of research - language records and comparisons, analysis of excavated materials, the relationship between antiquity sites and others from the colonial period.[1]

The first scholar to inquire into Brazil's past was Danish naturalist Peter Wilhelm Lund (1801-1880).[2] Lund lived much of his life in Brazil, and was responsible for studying several reminiscences of ancient plants in the caves of the Lagoa Santa region (Minas Gerais), where he settled between 1834 and 1880.[2][5] In his researches, he found human bones mixed in with these prehistoric remains, one of the first findings that contradicted Creationism. He was the first to defend the antiquity of American Man based on archaeological finds, but he failed to convince the scientific community of his time.[2]

Midden

Middens, shell mounds, and other debris accumulated by human action were archeological remains responsible for stirring scientific debate in the 19th century.[5] Ladislau Netto, director of the National Museum of Brazil - which together with the Ipiranga Museum, represented the official interest in the archeological-historical facts in the country - sent the first scientific expeditions to these regions. After years of research, these missions claimed that "shell mounds" would have anthropogenic formation, i.e. human origin. Hermann Von Ihering, however, the director of the Ipiranga Museum, first opposed this view, stating that the shell remains would have been formed by natural, intertropical phenomena.[2]

Between 1880 and 1900, the first excavations in the Amazon took place.[1][2] Extensive discoveries of Marajoara ceramics were made in this period,[1] and were analyzed in 1882 by Egyptologist Paul l'Epine, who believed he identified Egyptian and Asian spellings on the indigenous ceramics. Émil Goeldi also conducted important research in Brazil's northern region at that time.[6] The Austrian J. A. Padberg-Drenkpohl, hired after World War I by the National Museum, was another important figure in the history of Brazilian archaeology, who excavated at Lagoa Santa between 1926 and 1929. His goal was to find traces that would prove Lund's classic findings. Drenpohl, however, was not successful in his enterprise, and he went on to criticize the defenders of the antiquity of man from Lagoa Santa. In 1934, shortly after Drenkpohl's last expedition, Angione Costa published the first manual of Brazilian archaeology.[2]

After 1950, official archaeology diminished, while the number of amateurs who began to carry out research in the country increased. One of these was Guilherme Tiburtius, a German immigrant in Curitiba, who conducted one of the most important searches for Indian antiquities in Brazil, collecting artifacts for his collection (received by Joinville's Sambaqui Museum). He studied the coast of Santa Catarina and the plateau of Paraná and was assisted in his research by the Federal University of Paraná. Harold V. Walter, the English Consul in Belo Horizonte, was responsible for research in the state of Minas Gerais, in the region of Lagoa Santa. Although he used a methodology that is not accepted nowadays, he contributed to the collection of information about the Pleistocene era. Even at this time, substantial efforts were made to preserve Brazil's historical heritage. Thanks to the efforts of several intellectuals, the Prehistory Institute of USP (currently integrated into MAE)[7] was created, while a few years later (1961), new legislation on heritage was enacted.[2] Accompanying this advance in the question of preservation of Brazilian memory, excavations were carried out at the mouth of the Amazon river by Clifford Evans and Betty J. Meggers between 1949 and 1950, discovering important ceramic artifacts, and in São Paulo and Paraná between 1954 and 1956 by Joseph Emperaire and Annette Laming - where the first Carbon-14 datings were made.[2][8]

The recent history of archaeology in Brazil includes the creation of PRONAPA (National Project for Archaeological Research)[9] with the assistance of IPHAN,[10] which aims to conduct searches to provide a more complete picture of the Brazilian historical-cultural past. Meanwhile, institutions such as the National Museum, the Ipiranga Museum, and the Prehistory Institute conducted isolated research, and the Émil Goeldi Museum launched a project called PRONAPABA (National Project of Archaeological Research in the Amazon Basin). Several studies have been conducted since then on middens, Brazilian rock painting,[1] and lithic industry. In 1980, the first Brazilian Archaeological Society was created.[11][12] Archaeology is now taught in Brazil, although in a limited way.[5]

Pleistocene (60,000 - 12,000 BP)

Territorial occupation

The occupation of American territory is a topic that has generated substantial controversy, especially as many archaeologists are still reluctant to accept that man could have arrived in the Americas by other routes than the Bering land bridge.[1][13] However, discoveries made in Brazilian archaeological sites have called into question the validity of this theory.[1] In Piauí, for example, a fossil of the roundworm Ancylostoma duodenale was found with a date of 7,750 BP. According to some archaeologists, this Old World species could not have survived the Beringian crossing, because it would have died from the cold. Thus, they believe that the existence of the fossil indicates the migration of people from warm regions of the globe. Finds in Minas Gerais and Bahia have been dated between 25,000 and 12,000 BP[1] At the Alice Boer archaeological site in São Paulo, pieces dating back to 14,200 BP have been found.[14] In São Raimundo Nonato, in Piauí, archaeologists advocate an age of 50,000 years for a shelter occupied by prehistoric man.[1] Also at this same site, archaeologists were able to find human artifacts dating back to more than 48,000 BP[15]

The discoveries in Brazil led to polemics about the traditional view of the occupation of the Americas[16] and archeologists started to defend other theories about the great migrations, among them, that Man arrived in the Americas between 150,000 and 100,000 years ago, arriving by Malay-Polynesian (from Southeast Asia) or Australian (from the South Pacific) currents, while other authors still think of a migration current originating in Africa. The similarities between the material traces found in the Americas and those found in Oceania contribute to these theories. It can be generally admitted that Brazil was occupied 60,000 years ago, as far as Piauí is concerned.[17] Migratory currents would have reached Minas Gerais 30,000 years ago and Rio Grande do Sul 15,000 years ago.[18]

Luzia Woman

Luzia is the name of the oldest human fossil found in the Americas.[19] Charcoal near the fossilized remains was dated to about 11,000 years before present. Found by French archaeologist Annette Laming-Emperaire in the 1970s at the archaeological site of Lapa Vermelha, in the municipality of Lagoa Santa (Minas Gerais), the fossil of this prehistoric woman contributes to reigniting an old debate about the origins of humans in the Americas.[19] According to paleoanthropologist Walter Neves, responsible for naming the fossil, the morphology of Luzia's skull would bring her closer to the current aborigins of Australia and natives of Africa.[19]

Neves ventured the hypothesis that the occupation of the Americas was older than previously imagined, although not going back very far in time (about 14,000 years before the present), and that it was carried out by peoples from distinct regions, such as Oceania and Africa.[20] This thesis was not well received by some scientists.[19] According to National Geographic, besides races not being a scientific way to classify human beings, the differentiations between human groups only emerged after 9.5 thousand years.[21]

The people of Luzia

Studies conducted in the region inhabited by Luzia and other Paleo-Indians show that they were unaware of pottery and that their lithic industry was relatively simple.[22] Recent research, however, claims that these men were sedentary. Findings such as numerous burials and the use of raw materials existing only at this site have reinforced these ideas. An analysis of cavities in the teeth of these Americans shows that they, although having no agriculture, drew heavily on plant resources.[23]

Holocene in Brazil (12,000 - 4,000 BP)

Archaeologists call a "phase" a cultural complex where the elements are closely associated. By "tradition" archaeologists mean the standard practices and techniques of the ancients for making, for example, lithic industry and cave paintings. A subtradition is a split within the tradition, usually because there has been a differentiation of the original pattern into two or more new patterns.[2]

At the end of the Pleistocene period, the temperature varied widely in phases of glacier expansion and contraction. It is believed that temperatures were cooler in the Pleistocene than in the Holocene when they experienced a considerable increase. At the beginning of the Middle Archaic period, the sea level was 10 meters lower than it is today. Many regions of the country, such as Piauí, for example, were much wetter than they are today.[19]

Northeast and Center-South Brazil

The Brazilian Paleolithic age is usually situated between 12,000 and 4–2,000 years before the present when the agricultural practice emerged and spread in the region.[24] Before that time, Man lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering, a fact proven by archeological findings and representations in pre-Cabraline paintings. At this time, archaeologists found different types of lithic industries in several regions of Brazil. In the northeast, several archeological sites indicate the development of chipped stone, containing slugs (a slug-shaped lithic artifact used to scrape wooden supports), splinters, awls, and stoves for roasting meat. Rock art was carried out at these early sites.[19]

In the northeast region, the techniques for working with lithic material became increasingly diversified and complex over time. The number of stoves, for example, increased as dating approached the year 8,000 before the present. Campfires were also found.[24][25]

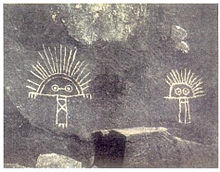

The cave paintings of this region have been instigating experts. In the Baixão da Perna 1 cave, for example, (in the archeological area of São Raimundo Nonato) cave paintings dating back 10,500 years have been found. At the site of the Boqueirão da Pedra Furada, numerous cave paintings in red pigment were found. The authors identify the painting tradition of this area as the "northeast tradition".[26] Besides the northeast tradition, subtraditions such as Várzea Grande (southeast of Piauí) and Seridó (Rio Grande do Norte) have been identified. The most abundant figures represent human beings, plants and animals, but purely abstract graphisms are also found. Some cave walls depict hunting scenes and ritual celebrations. According to some archaeologists, the themes of violence in ancient rock art would be linked to the technical development achieved in subsequent years, responsible for promoting more efficient hunting strategies. The northeastern tradition concluded about 5,000 years ago.[27]

In the central and northeastern region, an important cultural tradition has been identified by scholars: The "Itaparica tradition" (Goiás, Minas Gerais, Pernambuco, Piauí). This tradition developed lithic tools like slugs, awls, and knives, but few projectile points. The people of these regions changed their way of life about 6,500 years ago when they began to eat mollusks and fruits.[28] In the center of the country, a tradition of rock paintings called "Planalto" developed.[29]

The oldest dates in the South are attributed to the "Ibicuí tradition" (between 13,000 and 8,500 years old), composed of simple artifacts found in the Uruguay Basin.[1][2] The Uruguay phase, which succeeds the first chronologically, dates from 11,555 to 8,640 BP and is composed of scrapers, bifacial blades, and projectile points.[30] In Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul, artifacts (knives, scrapers, arrowheads) from 8,500 to 6,500 years ago have been located, established as the "Vinitu tradition". The more recent "Humaitá tradition" (between 6,500 and 2,000 years ago) extends from São Paulo to Rio Grande do Sul.[2][24] The Man of this tradition produced scrapers, awls, and even zooliths (stone statues in the shape of animals). Another tradition identified in the south was called "Umbu"; this one would have been responsible for making stoves and projectile points.[1][19][31]

The main archaeological sites on the coast are the middens.[1][32][33][34] Usually, skeletons of ancient Americans, lithic pieces, food remains, are found near them. A large part of the Brazilian middens are covered by the sea, due to the climatic changes that occurred during the late Pleistocene and Holocene. They exist almost everywhere along the Brazilian coast. At the time of their discovery, in the 19th century, they were compared to similar structures in Scandinavia. Middens are associated with the "Itaipu tradition". The people who inhabited the coast are usually defined as semi-nomadic fishermen.[1][35]

Recent Archaic from the south to the northeast regions (4,000 BP to 1,500 A.D.)

The appearance of cultivated plants in Minas Gerais dates back 4,000 years.[36] In São Raimundo Nonato, agriculture has likely been practiced since at least 2,090 years ago. Although Amazonian pottery is older than agriculture, the same phenomenon does not occur in the rest of the country, where the oldest pottery dates back 3,000 years (also in the area of São Raimundo Nonato). Brazilian archeologists consider that the appearance of pottery in these regions is linked to sedentarism and agriculture since pottery is difficult to transport and usually had the function of storing food. The "Taquara-Itaré tradition" is probably the most studied pottery tradition in the country.[1]

Pre-Ceramic period (Amazon) (12,000 - 3,000 BP)

The oldest records of inhabitants in the Amazon region are dated as early as 12,500 B.C. Likely, the territory had already been colonized earlier, but only further research in the Amazon will be able to confirm this hypothesis. Archeologists identified the development of stone chipping techniques, starting with percussion flaking and moving on to pressure flaking.[37] The changes in flaking techniques are associated with different types of hunting, one targeting large animals and the other small animals. Nothing, however, is certain about the hunting style of the ancient Amazonian peoples. Scholars believe that these peoples fed on mollusks (an observation based on the discovery of sites such as midden), small animals, and fruits. Middens remain the main archaeological sites of this period in the Amazon.[37]

Amazon agriculture

New research in Rondônia attributes greater antiquity to the practice of agriculture in the Amazon. According to archeologist Eduardo Bespalez, Amazonian agriculture can reach 8,000 years, a date close to the first records of agriculture in the world.[38] Furthermore, the Garbin archeological site reinforces the thesis that pottery was not, in its origins, associated with agriculture.[38] Brazilian archaeologists have found only lithic industry associated with terra preta (the main indication of the practice of agriculture in the region). The new findings may shed light on the mysteries surrounding everything from the significance of complex societies in the Amazon to the origins of the Amazon rainforest, possibly anthropogenic.[38] According to archaeologist Marcos Pereira Magalhães,

"The Amazonian Neotropical Culture is the result of a long-term regional historical event, derived from the Tropical Culture developed by hunter-gatherer societies socially, culturally, and economically integrated with the resources of the Neotropical rainforest, with which they interacted objectively and subjectively."[39]

Early ceramic period (3,000 - 1,000 B.C.)

During this time, the Amazonian peoples adopted a lifestyle similar to the lifestyle adopted by many tribes in the territory today. Thus, the indigenous people would have lived in a state of relative settlement, performing horticulture. These groups developed the first elaborate pottery in the Americas, with geometric and zoomorphic themes, and paintings in white and red paint.[40] The vessels took on oval and circular shapes. The best-known groups of ceramic styles are called "Hachurado-Zonado" and "Saldóide Barrancóide". The latter is related to red and white incisions and paintings, while the former is to the preference for ornate decoration.[1] "Saldóide Barrancóide" ceramics, found in the lower and middle Orinoco, were likely created between 2,800 and 800 B.C.. The "Hachurado-Zonado" styles of Tutoshcainyo and Ananatuba date from around 2,000-800 B.C. and 1,500-500 B.C. respectively. Many scholars have admitted that this pottery was influenced by Andean cultural complexes, although it is now accepted that Amazonian indigenous people developed this elaborate pottery in the lower region themselves, and probably influenced the Andes at a later date.[1] The "Saldóide Barrancóide" style is also believed to have been created in the lower Orinoco.[1]

In addition to horticulture, these societies practiced hunting and fishing. Shellfish consumption was reduced, and these peoples began to settle in the floodplains and riverbanks. Coarse pottery bowls have been identified in these territories, so that some archaeologists hypothesize the presence of cassava. Sites of these cultural complexes have been found in the Ucaiali basin, on Marajó Island, in the Orinoco and in the Amazon.[1]

Amazonian complex cacicados (1,000 B.C. - 1,000 A.D.)

The demographic increase of Amazonian populations in late Prehistoric times, combined with other factors, gave rise to major transformations among the indigenous societies of the Amazon.[41] According to archaeologists, the societies inhabiting regions of the Amazon basin began to organize themselves in increasingly elaborate ways between 1,000 B.C. and 1,000 A.D.[1] Archaeologists define these societies as "complex cacicados."[42] These societies became increasingly hierarchical containing nobles, "commoners" and captive servants,[42] with a centralized leadership in the figure of the cacique, and adopted bellicose and expansionist attitudes. The chieftain, besides dominating large territories, continuously organized his warriors to conquer new territories. The pottery of these societies was highly elaborate, demonstrating mastery of complex production techniques. There were elaborate funerary urns (associated with the cult of the dead chiefs) and trade. Archaeological evidence points to an urban-scale population density in these civilizations.[43] It is believed that monoculture was practiced, in addition to intensive hunting and fishing, intensive root production, and food storage.[44][1] According to researcher Anna Roosevelt,

"The development of intensive agriculture in prehistoric times seems to have been correlated to the rapid expansion of the populations of complex societies. Suggestively, the displacements and depopulation of the historical period caused these economies to return to patterns of less intensive root cultivation and animal capture (...)."[42]

Chronicles from the early colonial period are employed today in the reconstruction of ancient Brazilian civilizations. Many foreign chroniclers have described indigenous elements from the period of the complex cacicados. The dissolution of these social organizations is usually related to the conquest, which affected their demographic structure.[45]

The ceramics produced by these civilizations are classified into two main groups: the "Horizonte Policrômico" and the "Horizonte Inciso Ponteado". Among the archaeological sites that presented vestiges grouped under the "Horizonte Policrômico" are: The Marajoara (mouth of the Amazon) and the Guarita (Middle Amazon), among others located outside the Brazilian Amazon. Archaeological sites associated with the "Horizonte Inciso Ponteado" include Santarém (Lower Amazon) and Itacoatiara (Middle Amazon). The first Horizon ("Horizonte") is characterized by white, black, and red paintings, geometric themes, and incisions. The second horizon is characterized by deep incisions and the dotting technique. It is believed that the "Horizonte Inciso Ponteado" was associated with the ancestors of the Cariban-speaking peoples, while the "Horizonte Policrômico" would have been produced by the ancestors of the Tupi-speaking peoples.[45]

The large Amazonian sites of the complex cacicado epoch were probably specialized regions for burial, worship, work, and warfare. The late prehistoric occupation of the territory was sedentary. The entry of maize and other seeds into the region, as well as their popularization among Americans, dates back to the first millennium before Christ.[46]

Kuhikugu (1,500 - 400 A.D.)

One of the Amazonian civilizations known to have developed large cities and towns during the pre-Cabraline period was Kuhikugu.[47] The archaeological site, discovered by archaeologist Michael Heckenberger, is located within the Xingu National Park (Upper Xingu region) and proved to have been a large urban complex that may have housed up to 50,000 inhabitants. Probably built by the ancestors of the current Kuikuro people, the site houses complex constructions such as roads, fortifications, and trenches for protection. As the discovery is recent, studies on the ways of life of these populations are still needed, although scholars believe that these people cultivated cassava.[48] The disappearance of this civilization, as well as other great Amazonian civilizations, is related to the entrance of European diseases into the continent, responsible for decimating the local populations at around 1,500 of the present era. The natural characteristics of the Amazon Rainforest (dense forest, etc.) would explain why the ancient Europeans did not make acquaintance with this Brazilian civilization.[49]

Mount of Teso dos Bichos (400 BC - 1,300 A.D.)

Teso dos Bichos or Tesos Marajoaras, located on Marajó Island, is the site where one of the most elaborate civilizations of the pre-Cabraline Amazon were born, occupying 2.5 hectares.[50] One of the distinguished features of the complex societies of Marajó Island is the "tesos", large artificial embankments built to place dwellings, probably to avoid flooding. Marajoara tesos are considered monumental structures and, for this reason, are essential for the interpretation of the Marajoara past.[50]

Anthropogenic hill formation

It was estimated that the civilization responsible for the work would have a population of 500,000 people. The inhabitants of this civilization would belong to a society of Tuxaua, lords of the mouth of the Amazon River. There would be a division of labor between men and women, a diet rich in protein (animal and vegetable), and fermented beverages (such as aluá).[51]

Formation by fluvial sedimentation of the hill

In October 2009, a group of geologists claimed that the tesos could be essentially natural structures, by processes similar to fluvial mound formation elsewhere, with evidence of human activity only in more superficial layers.[52] Because they required significantly less human activity for their formation, complex societies would not have been necessary for the monumental accumulation of labor.[52] This hypothesis partially invalidates interpretations about the existence of complex societies in the Amazon.[53] Archaeologists responsible for the excavation and anthropogenic hypothesis have questioned the team's methodology, but admit that the lack of evidence of agriculture in the region corroborates the discovery.[53]

Main archeological sites

Alice Boer

The Alice Boer site is located in Ipeúna, a municipality near Rio Claro, in São Paulo. It was excavated by archaeologist Maria Beltrão at the service of the National Museum from 1964 onwards. The first Brazilians in the region were ancient and produced artifacts such as projectile points, scrapers, and slugs. A charcoal sample from this site provided a date of 14,200 years.[54][55]

Abismo da Ponta de Flecha

The Ponta de Flecha site was excavated between 1981 and 1982 by C. Barreto and E. Robrahn. The findings from the site - among them arrowheads and bones - date back to both the Pleistocene and Holocene times. The animal bones found were marked by human lithic instruments.[56]

Pedra Pintada

Anna Roosevelt (great-granddaughter of U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt), a professor of anthropology at the University of Illinois, coordinated in 1996 a team that researched the Pedra Pintada Cave in Monte Alegre, Pará, on the left bank of the Amazon River, a few kilometers from what is now Santarém.[57]

The prehistoric inhabitants of that region supported themselves with a stable economy and produced culture and technologies. The Paleoindians lived in comfortable and protected caves, had a healthier diet, and produced pottery, cave paintings, and arrowheads. They were hunters of small animals and gatherers of fruit. At the height of their civilization, they might have reached as many as 300,000 individuals.[58]

Spearheads and pottery shards dating back 10,000 to 6,000 years were found there. The results concluded that the Paleoindians (the first inhabitants of the Americas) lived in the Amazon region from 11,200 to 10,000 years ago. This serves as evidence that human occupation in the continent took place more than 20,000 years ago.[58]

Still, Roosevelt's findings have not yet fully refuted the hypothesis of the arrival of the first inhabitants of the Americas through the Bering Strait. The migratory movement would have occurred in successive waves. The Amazonian populations, whose signs she found in the Pedra Pintada cave, probably migrated south without having had contact with American mammoth hunters.[59]

Pedra Furada

The archaeological site of Pedra Furada,[60] located in São Raimundo Nonato, in the Serra da Capivara National Park, Piauí, was discovered in the 1960s. It has been studied since the 1970s by Niède Guidon, a French-Brazilian archaeologist. The findings (chipped stones and traces of bonfires) date back approximately 11,000 years. According to the team, it is not unlikely that the discoveries could be up to 48,000 years old. Guidon's thesis goes much further - about 100,000 years - and assumes that Man did not arrive in America from Asia by land (via the Bering Strait as is believed until today), but by sea, using boats. However, the findings of São Raimundo Nonato remain controversial and do not yet fully refute the Clovis Theory.[60]

The site also houses the Museum of the American Man. Illuminated explanatory panels tell the story of the presence of man in the Americas with drawings, maps, and texts. The space also holds clay funerary urns and replicas of two human skeletons found in caves in the region. One of them, a 30-year-old Indian woman, was found practically complete and dates back to 9,700 years ago.[61]

Drawings were found as well in the Toca do Boqueirão, also in Pedra Furada, which likely represent a scene of an attack by the felines that once inhabited the continent. The conceptions of the current Indians living in the northeast region of the country, like the Kiriri, although much modified, may still be a useful element to decipher such representations with a conjectural strategy. The drawings are described by the Kiriri, in general, as huge men, ferocious and implacable, with rude features and wide-open eyes, truly frightening. According to anthropologist Nascimento, who studied in his Master's thesis for the Federal University of Bahia the rituals and ethnic identification of the northeastern Indians based on the conceptions of a remnant group - the Kiriri of Mirandela (Bahia) in 1994.[62]

-

Serra da Capivara, Piauí

-

Serra da Capivara, Piauí

-

Serra da Capivara, Piauí

-

Catimbau Valley, Pernambuco

Lagoa Santa

In Brazil, besides the remains from Piauí, there is also an ancient set found in the region of Lagoa Santa (Minas Gerais), possibly the representatives of the country's ancient linguistic group Macro Jê, whose closest descendants today would be the Kiriri and Botocudo Indians.[63][64][65]

In 1974, at Lapa Vermelha IV, during the excavation of Annette Laming-Emperaire's team, a human skeleton dated 11,500 years BP, the oldest in the Americas, was discovered, later nicknamed Luzia. She cast doubt on the Clovis Theory since she is a woman with characteristics very distinct from today's indigenous people (who are closer to the epigenetic Mongoloid group). Luzia was investigated by bioanthropologists and archaeologists Walter Alves Neves, André Prous, Joseph F. Powell, Erik G. Ozolins, and Max Blum.[66]

Recent pre-Cabraline period

While most research on earlier Brazil has mainly analyzed the material remains left by these peoples, recent pre-Cabraline Brazil is usually studied through the native languages. The study of native languages allows us to understand many aspects of these cultures, as well as their historical affiliations and migrations. When European chroniclers described the ancient Brazilian peoples, they mostly used linguistic names and, thanks to the missionary work of some Jesuits, today we know the ancient Brazilian languages (which gave rise to modern indigenous languages).[67][68]

When Europeans came to occupy the eastern coast of South America, they encountered ethnic groups linked to four main language groups: The Arawak, the Tupi-Guaraní, the Jê, and the Kalinago.[67]

Tupi

One of the most relevant linguistic groups in Brazil, and one which likely spread in a large scale over Brazilian territory before 1500, is the Tupi group. The main language family within this larger group is the Tupi-Guaraní. These peoples may have first inhabited the headwaters of the Madeira, Tapajós and Xingu rivers.[69][70] The Tupi-Guaraní expansion happened between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago, shortly after this group differentiated from others in the region between the Xingu and Madeira rivers, forming new language subgroups, such as the Cocama, Omágua, Guaiaqui, and Xirinó. The Cocama and Omágua peoples headed to the Amazon River, while the Guaiaqui went to Paraguay and the Xirinó to Bolivia. The Tapirapé and Teneteara moved toward the northeast. The Pauserna, Cajabi, and Kamayurá peoples moved to the extreme southern region of Brazil.[69][71]

The Wayampi-speaking peoples reached as far as the Guianas region. The last phase of dispersion of the Tupi-Guaraní peoples occurred around the year 1,000. The speakers of languages associated with the Tupi-Guaraní family were already settled in southern Brazil (Guaraní, for example), in the Amazon basin, and also on the coast of Brazil (Potiguara, Tupinambá, Tupiniquin). Thanks to an extensive network of waterways, the peoples of this linguistic group were able to spread out and at the same time maintain contact with each other.[69][71]

Many archaeological artifacts from the ceramic period are affiliated with these ancient peoples of the Tupi-Guaraní linguistic matrix. The archaeological sites associated with these peoples were extensive villages, usually located on plateau or terrace regions. In these archaeological sites, averaging between 10,000 and 2,000 square meters in width, ancient pottery was abundant.[69][72]

The chronology of the history of the Tupi-Guaraní peoples is based on archeological theories, glottochronology, and the dating of ceramics identified. As demonstrated by the history of the Tupi-Guaraní from their languages, the expansion movement occurred between 3,000 and 2,000 years ago from the Amazon region; most of the archeological artifacts of these peoples are dated between the years 500 and the year 1,500. The time of the expansion to the coast is verified by the highest concentration of artifacts in this region between the 11th and 13th centuries.[73]

Macro-Jê

The Macro-Jê expansion began 3,000 years ago in the Midwest Region of Brazil. The Jê group itself possibly originated in the headwaters regions of the São Francisco and Araguaia rivers. A large part of the Jê speaking peoples moved away from the Kaingang and Xokleng to the south of the Central Brazilian region.[1] Some groups must have separated from the latter and moved into the Amazon region at least a thousand years ago. The Jê peoples preferred to settle in plateau regions (such as the original Brazilian Plateau region), evidenced by study of their languages among the languages of the Macro-Jê trunk, which are Kayapo, Xerente, Timbira, among others.[1]

16th-century Brazil

On the eve of the arrival of Europeans in America in 1500, it is estimated that the current territory of Brazil (the eastern coast of South America) was inhabited by two million indigenous people, from north to south.[74]

According to Luís da Câmara Cascudo, the Tupi were the first "indigenous grouping that had contact with the colonizer."[75]

The names of some of the main groups that inhabited Brazil on the eve of the European arrival are (among them some of non-Tupi origin): The Potiguara, Tremembé, Tabajara, Caeté, Tupiniquim, the Tupinambá, Aimoré, Goitacá, Tamoio, Carijó and Temiminó. The Potiguara inhabited the region between the Acaraú and Paraíba rivers and controlled the river navigation. During the conquest, they were allied with the French, and some accounts speak of marriages between Potiguara and French, involving anti-Portuguese war agreements.[68][1][69] The Tabajara inhabited the southern bank of the Paraíba River, in what is now the coastal region of Pernambuco. They were important allies of the Portuguese during the conquest. The Caetés inhabited the region of Pernambuco from Olinda, "the Marim of the Caetés", to where the state of Alagoas is today, dismembered from Pernambuco.[68][1][69]

The Tremembé inhabited the western bank of the Acaraú river. The Tamoio inhabited the Guanabara Bay; their leaders were also allied with the French in the fight against the Portuguese. The Carijós inhabited the southern coast of the country. The Tupiniquim inhabited the present-day region of the state of São Paulo, and the Tupinambá the southeast region of Brazil.[68][1][69] The current knowledge of ancient Tupi is mainly based on the language of the Tupinambá.[76]

The Tupi peoples lived in villages of 600 to 700 inhabitants. Some villages were fortified because of inter-tribal wars. No authority appeared with absolute or considerably strong power over the other members of the society, although there were "hierarchies" according to gender, warrior merit and shamanic powers. Pajés (payes in ancient Tupi, intermediaries between the religious world and the world of men) and caciques (morubixaba in ancient Tupi for "warrior chiefs") generally occupied the role of tribal authorities.[2][77][78] The men believed in good and bad spirits (Tupã, Anhang, among others), who influenced events in the cosmos. Each man carried a maraca, in which they believed a spirit protector of each individual dwelled. It is believed that only the sons of the most important men of the tribe were buried in the funerary urns. The religious events had a wide scope, and brought together different ethnic groups. The ancient Indians were responsible for numerous artistic manifestations, such as pottery pieces, dances, songs/poetry and, the one that impressed Westerners the most, the sophisticated and rich featherwork.[79] Tupi literature appears with the arrival of European writing, when missionaries started writing in Tupi to convert the natives,[76] and chronicles transcribed indigenous songs.[80]

Other indigenous groups

Other groups, with debated theories on their origins and their languages that have inhabited Brazil since pre-Cabraline times are:[81]

Pre-Cabraline Brazil in Europe

On the European side, the discovery of Brazil was preceded by several treaties between Portugal and Spain, establishing limits and dividing the world already discovered from the world yet to be discovered.[84][85]

Of these agreements signed at a distance from the assigned land, the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) is the most important, for defining the portions of the globe that would belong to Portugal during the period in which Brazil was a Portuguese colony.[86][84] Its clauses established that the lands east of an imaginary median that would pass 370 maritime leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands would belong to the kingdom of Portugal, while the lands to the west would be owned by the kings of Castile (now Spain). In the current Brazilian territory, the line crossed from north to south, from the current city of Belém to Laguna.[84]

See also

- History of Brazil

- Pre-Columbian era

- Mesoamerica

- Andean civilizations

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab da Cunaha, Manuela Carneiro (2008). História dos Índios no Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. ISBN 9788571642607.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Prous, André (1991). Arqueologia brasileira (in Brazilian Portuguese). Editora Universidade de Brasília. ISBN 978-85-230-0316-6.

- ^ Guzmán, Décio de Alencar (7 February 2005). "Carlos Fausto, Os índios antes do Brasil.,Rio de Janeiro, Jorge Zahar Editor, 2000. 94 pp. (Coleção "Descobrindo o Brasil")". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.398. ISSN 1626-0252.

- ^ Costa, Angyone (1980). Introdução à arqueologia brasileira: (etnografia e história) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Companhia Editora Nacional. ISBN 978-85-04-00040-5.

- ^ a b c Ambientebrasil, Redação (6 January 2009). "Arqueologia no Brasil". Ambientebrasil - Ambientes (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ "Emílio Goeldi — Este site está sendo migrado... Clique aqui para acessar novos conteúdos em gov.br/museugoeldi Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi". www.museu-goeldi.br (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- ^ "Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia". mae.usp.br.

- ^ Quantos anos faz o Brasil? (in Brazilian Portuguese). EdUSP. 2000. ISBN 978-85-314-0546-4.

- ^ "Projeto Nacional de Pesquisas Arqueológicas»" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Página Inicial". Instituto do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Schaan, Denise Pahl; Bezerra, Márcia (2009). Construindo a arqueologia no Brasil: a trajetória da Sociedade de Arqueologia Brasileira (in Portuguese). G K Noronha. ISBN 978-85-62913-00-6.

- ^ "Sabnet". Sabnet (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Jablonski, Nina G. (2002). The First Americans. California Academy of Sciences. ISBN 9780940228504.

- ^ "Sítio Arqueológico Alice Boer" (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ^ "Parque Nacional Serra da Capivara". FUNDHAM (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Angelo, Claudio (21 March 2005). "Crânios sugerem que povo de Luzia habitou México e São Paulo". Folha de S. Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Martin, Gabriela (1997). Pré-história do Nordeste do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Editora Universitária UFPE. ISBN 978-85-7315-083-4.

- ^ Vialou, Águeda Vilhena (2005). Pré-história do Mato Grosso: Cidade de Pedra (in Brazilian Portuguese). EdUSP. ISBN 978-85-314-0917-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Melatti, Julio Cezar (2007). Indios do Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). EdUSP. ISBN 978-85-314-1013-0.

- ^ "Luzia (fóssil)", Wikipédia, a enciclopédia livre (in Portuguese), 3 April 2023

- ^ "Who were the first americans?". National Geographic.

- ^ Neves, Walter A.; Piló, Luís Beethoven (2008). O povo de Luzia: em busca dos primeiros americanos (in Brazilian Portuguese). Editora Globo. ISBN 978-85-250-4418-1.

- ^ "Primeiros brasileiros eram sedentários, sugerem pesquisas". www.jornaldosite.com.br.

- ^ a b c Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo. 2005.

- ^ Xavier, Leandro Augusto Franco (12 February 2008). Arqueologia do Noroeste Mineiro: análise de indústria lítica da bacia do Rio Preto - Unaí, Minas Gerais, Brasil (text thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ "FUMDHAM - Pinturas rupestres". Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ "Incrições Rupestres Serra da Capivara - Ache Tudo e Região". www.achetudoeregiao.com.br.

- ^ Lourdeau, Antoine (1 January 2015). "Lithic Technology and Prehistoric Settlement in Central and Northeast Brazil: Definition and Spatial Distribution of the Itaparica Technocomplex". PaleoAmerica. 1 (1): 52–67. doi:10.1179/2055556314Z.0000000005. ISSN 2055-5563. S2CID 140659852.

- ^ Lourdeau, Antoine (19 January 2008). "A Pertinência de uma Abordagem Tecnológica para o Estudo do Povoamento Pré-histórico do Planalto Central do Brasil". Habitus. 4 (2): 985. doi:10.18224/hab.v4.2.2006.985-710. ISSN 1983-7798.

- ^ Soares, André Luis Ramos (12 January 2005). Contribuição à Arqueologia Guarani: estudo do Sítio Röpke (text thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ Schiavetto, Solange Nunes de Oliveira (2003). A arqueologia guarani: construção e desconstrução da identidade indígena (in Portuguese). Annablume. ISBN 978-85-7419-363-2.

- ^ Capanema, Guilherme Schuch de (1876). Os Sambaquis (in Portuguese). Brown & Evaristo.

- ^ Gaspar, Madu (2000). Sambaqui: arquelogia do litoral Brasileiro (in Brazilian Portuguese). Jorge Zahar Editor. ISBN 978-85-7110-530-0.

- ^ Duarte, Paulo (1968). O sambaqui: visto através de alguns sambaquis (in Brazilian Portuguese). Instituto de Pré-História.

- ^ Roosevelt, Anna Curtenius (1991). Moundbuilders of the Amazon: Geophysical Archaeology on Marajo Island, Brazil. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-595348-1.

- ^ Silverman, Helaine; Isbell, William (4 April 2008). Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-75228-0.

- ^ a b Meggers, Betty Jane (1974). A reconstituic̃ão da pré-história amazônica: algumas considerações teóricas (in Brazilian Portuguese). Instituto de Geografia da Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ a b c "MidiaNews | Agricultura em sítio arqueológico de RO pode ter 8 mil anos". MidiaNews. 24 October 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Magalhães, Marcos Pereira. "Evolução antropomorfa da Amazônia" (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Gomes, Denise Maria Cavalcante (2002). Cerâmica arqueológica da Amazônia: vasilhas da colec̜ão Tapajônica Mae-USP (in Brazilian Portuguese). EdUSP. ISBN 978-85-314-0616-4.

- ^ Roach, John. "Ancient Amazon Cities Found; Were Vast Urban Network". National Geographic. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Roosevelt, Anna (1994). Amazonian Indians from Prehistory to the Present: Anthropological Perspectives. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1821-0.

- ^ "Ancient Amazon Civilization". Discovery News. Archived from the original on 8 January 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ Paiva, Maurício de (2009). Amazônia antiga: arqueologia no entorno (in Portuguese). DBA. ISBN 978-85-7234-401-2.

- ^ a b Bethell, Leslie (1997). História da América Latina: América Latina Colonial Vol. 2 (in Brazilian Portuguese). Edusp. ISBN 978-85-314-0497-9.

- ^ "acroosevelt.net - Registered at Namecheap.com". www.acroosevelt.net. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Kuikuro - Povos Indígenas no Brasil". pib.socioambiental.org. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Science -- Heckenberger et al. 301 (5640): 1710". plaza.ufl.edu. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Biello, David. "Ancient Amazon Actually Highly Urbanized". Scientific American. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b "Moundbuilders of the Amazon : geophysical archaeology on Marajo Island, Brazil | WorldCat.org". www.worldcat.org.

- ^ Souza, Márcio (2001). Breve história da Amazônia (in Brazilian Portuguese). AGIR. ISBN 978-85-220-0533-8.

- ^ a b de Fátima Rossetti, Dilce; Góes, Ana Maria; Mann de Toledo, Peter (2009). "Archaeological mounds in Marajó Island in northern Brazil: A geological perspective integrating remote sensing and sedimentology". Geoarchaeology. 24 (1): 22–41. doi:10.1002/gea.20250. S2CID 55092997.

- ^ a b "Folha de S.Paulo - Povos antigos não fizeram aterros no Pará, diz grupo - 19/10/2009". www1.folha.uol.com.br.

- ^ "A Pré-história Brasileira" (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese). 19 April 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ "Os Povos Guarani Na Região de Indaiatuba | PDF | Sociedade". Scribd. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Revista de pré-história (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo, Instituto de Pré-história. 1979.

- ^ "História da ocupação do Baixo Amazonas prova que humanos e floresta podem conviver". National Geographic (in Brazilian Portuguese). 8 July 2021. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ a b Pereira, Edithe da Silva; Moraes, Claide de Paula (26 August 2019). "A cronologia das pinturas rupestres da Caverna da Pedra Pintada, Monte Alegre, Pará: revisão histórica e novos dados". Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas (in Portuguese). 14 (2): 327–342. doi:10.1590/1981.81222019000200005. ISSN 1981-8122. S2CID 202015595.

- ^ Roosevelt, Anna C.; Douglas, John E.; Amaral, Anderson Marcio; Silveira, Maura Imazio da; Barbosa, Carlos Palheta; Barreto, Mauro; Silva, Wanderley Souza da; Brown, Linda J. (19 November 2009). "Early Hunter in the Terra Firme Rainforest: Stemmed Projectile Points from the Curuá Goldmines". Amazônica - Revista de Antropologia (in Portuguese). 1 (2). doi:10.18542/amazonica.v1i2.296. ISSN 2176-0675.

- ^ a b Guidon, Niede (1989). "On Stratigraphy and Chronology at Pedra Furada". Current Anthropology. 30 (5): 641–642. doi:10.1086/203795. ISSN 0011-3204. S2CID 143602429.

- ^ "Museu do Homem Americano – FUMDHAM" (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Nascimento, Marco Tromboni De S. (1994). "O T R O N C O DA J U R E M A: Ritual e etnicidade entre os povos indígenas do nordeste - o caso Kiriri" (PDF). UFBA. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Baeta, Alenice Maria Motta (19 April 2011). Os grafismos rupestres e suas unidades estilísticas no Carste de Lagoa Santa e Serra do Cipó - MG (text thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ Junior, Pugliese (28 February 2008). Os líticos de Lagoa Santa: um estudo sobre organização tecnológica de caçadores-coletores do Brasil Central (text thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ Strauss, André Menezes (20 August 2010). As práticas mortuárias dos caçadores-coletores pré-históricos da região de Lagoa Santa (MG): um estudo de caso do sítio arqueológico Lapa do Santo (text thesis) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Universidade de São Paulo.

- ^ Neves, Walter A.; Powell, Joseph F.; Prous, Andre; Ozolins, Erik G.; Blum, Max (1999). "Lapa vermelha IV Hominid 1: morphological affinities of the earliest known American". Genetics and Molecular Biology. 22 (4): 461–469. doi:10.1590/S1415-47571999000400001. ISSN 1415-4757.

- ^ a b "Panorama das Línguas Indígenas da Amazônia". www.comciencia.br (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ a b c d Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil : terra à vista! : a aventura ilustrada do descobrimento. Edgar Vasques. Porto Alegre, RS: L & PM Pocket. ISBN 85-254-1258-9. OCLC 73509776.

- ^ a b c d e f g "IBGE | Brasil: 500 anos de povoamento | território brasileiro e povoamento | história indígena". brasil500anos.ibge.gov.br. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Bueno, Eduardo (2003). Brasil: uma história (in Brazilian Portuguese) (2nd ed.). São Paulo: Ática.

- ^ a b "Os índios no Brasil". Só História (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Prous, André. (2006). O Brasil antes dos brasileiros : a pré-história do nosso país. Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar Editor. ISBN 85-7110-920-6. OCLC 80946412.

- ^ Noelli, Francisco (1996). "As hipóteses sobre o centro de origem e rotas de expansão dos Tupi". Revista de Antropologia. 39 (2): 7–53. doi:10.11606/2179-0892.ra.1996.111642. S2CID 142157171.

- ^ Noelli, Francisco S. "Os Antigos Habitantes do Brasil" (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ Cascudo, Luís da Câmara. Dicionário do folclore brasileiro (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. 2. p. 865.

- ^ a b "South American Indian languages - Grammatical characteristics | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "A Socialidade contra o Estado: a antropologia de Pierre Clastres" (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese).

- ^ "Reflexões sobre a contribuição de Pierre Clastres à Antropologia Política" (PDF) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Com Ciência - Arqueologia e Sítios Arqueológicos". www.comciencia.br. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Academia BRASIL-EUROPA. Ed.A.BISPO: Jean de Léry". www.academia.brasil-europa.eu. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ Cunha, Manuela Carneiro da (1992). História dos índios no Brasil (in Brazilian Portuguese). Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo. ISBN 978-85-7164-260-7.

- ^ Grimes, Joseph E., ed. (1972). Languages of the Guianas (PDF). Summer Institute of Linguistics of the University of Oklahoma.

- ^ Rouse, Irving (1992). The Tainos : rise & decline of the people who greeted Columbus. New Haven. ISBN 0-300-05181-6. OCLC 24469325.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c "Treaty of Tordesillas". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Madrid, Treaty of (1750) | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "Descobrimento do Brasil". Livro do Centenário (1500-1900) (in Brazilian Portuguese). Vol. III. Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional. 1902.

| Period in Brazilian history | |

|---|---|

| Pre-Cabraline

(antiquity until 1500) |

Colonial Brazil

(1500 to 1822) |