Xian (Taoism)

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese folk religion |

|---|

|

In Taoism, the concept of xian[a] is ascribed to a person or entity having a long life, or is understood to be immortal in some sense. The concept of xian has different implications dependent upon the specific context: philosophical, religious, mythological, or other symbolic or cultural occurrence.

In traditional thought, Xian refers to immortal beings who have attained supernatural abilities and a connection to the heavenly realms inaccessible to mortals, either through spiritual self-cultivation or worship by others.[2]

Description

Xian have been venerated from ancient times to the modern day in a variety of ways across different cultures and religious sects in China.[3][4][5] The Eight Immortals are a good example of xian sometimes being seen as folk heroes who can offer assistance to "worthy human followers" and whose existence fosters the relationship between the living and the dead. Sometimes, they and other xian were viewed as similar in nature to ghosts, rather than deities.[5][6] The Eight Immortals and other xian were thought to have powers linked to their tools that were ultimately of a single nature that can add to or subtract the lifespan of humans depending on the human's level of sin.[7]

Xian were also thought by some Taoists to be synonymous with the gods inside the body, and as beings that sometimes cause mortals (who could fight them with martial virtue and martial arts) problems.[8] Xian could be good or evil.[9]

The word xian semantically developed from meaning spiritual "immortality; enlightenment", to physical "immortality; longevity" involving methods such as alchemy, breath meditation, and tai chi, and eventually to legendary and figurative "immortality". A variety of synonyms exist for the word across the various conceptions of it, including zhenren, a word used in Taoism that can also refer to "god[s] and deified mortal[s]", both of which xian could also be seen as.[10] Taoist cults of immortality formed around a variety of issues and leaders, including many healing cults formed around charismatic leaders who used "medical magic".[5]

Xian were also thought of as "personal gods" who were formerly humans, and types of ascended humans who became them include "ascetics, scholars, and warriors."[11] "Taoists [who believe in them] pray to the[m]...to request help, and try to follow the examples the gods set while living."[11]

Victor H. Mair describes the xian archetype as:

They are immune to heat and cold, untouched by the elements, and can fly, mounting upward with a fluttering motion. They dwell apart from the chaotic world of man, subsist on air and dew, are not anxious like ordinary people, and have the smooth skin and innocent faces of children. The transcendents live an effortless existence that is best described as spontaneous. They recall the ancient Indian ascetics and holy men known as ṛṣi who possessed similar traits.[12]

Translations

The Chinese word xian is translatable into English as:

- (in Daoist philosophy and cosmology) spiritually immortal; transcendent human; celestial being

- (in Daoist religion and pantheon) physically immortal; immortal person; an immortal; saint,[2] one who is aligned with Heaven's mandate and does not suffer earthly desires or attachments.[13]

- (in Chinese alchemy) alchemist; one who seeks the elixir of life; one who practices longevity techniques by turning Shen to Jing.

- (or by extension) alchemical, herbal, shí liáo, or qigong methods for attaining immortality

- (in Chinese mythology) wizard; magician; shaman; sorcerer

- (in popular Chinese literature) genie; elf, fairy; nymph; 仙境 (xian jing is fairyland, faery)

- (based on the folk etymology for the character 仙, a compound of the characters for person and mountain) sage living high in the mountains; mountain-man; hermit; recluse

- (as a metaphorical modifier) immortal [talent]; accomplished person; celestial [beauty]; marvelous; extraordinary

- (in new-age conception) seeker who takes refuge in immortality (longevity for the realization of divinity); transcended person [self] recoded by the "higher self"; divine soul; fully established being

- (in early Tang dynasty folk religion conception) immortal being part of a small spiritual cabal who had immortal lifespans and supernatural powers, and were enlightened to the works of heaven, which assigned everyone else to "gloomy underworld jails",[14] "a fiery underworld",[15] and/or a mundane role in the afterlife[16] depending on how positively one viewed the afterlife

- (in Daoism and Chinese folk religion) a Daoist who was blessed to become immortal from death onwards[17] and/or a guardian of a village[18]

- (in Chinese Buddhism and Buddhist-inspired Taoist sects) a kind of deity or spiritual person[19][3] imported from Taoism

- (in Confucianism within some imperial courts and folk religion practice that believes in the three teachings) an ideal existence often associated with cult images made from bronze and with "everlasting life" that is synonymous with and a part of tian or an afterlife that combines elements of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, a higher reality (variably a yin-yang realm or a mountain world beyond reality that created jade that manifests in the real world), the Tao and the forces of nature, or existence itself or a being that a deceased person's soul should become[20][21][11][22]

- (in Fujian Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism, and folk religion) a boddhisatva, a buddha who is not Gautama Buddha or a being of comparable holiness and power over nature to one, or a type of god worshipped in temples[2]

- (in Korean Taoist-inspired new religions) a being subservient to heaven that helps humans[23][24]

The word xian

The most famous Chinese compound of xiān is Bāxiān (八仙 "the Eight Immortals"). Other common words include xiānrén (仙人, sennin in Japanese, "immortal person; transcendent", see Xianren Cave), xiānrénzhăng (仙人掌 "immortal's palm; cactus"), xiānnǚ (仙女 "immortal woman; female celestial; angel"), and shénxiān (神仙 "gods and immortals; divine immortal"). The Three Sovereigns had similarities to xian because of some of their supernatural abilities and could have been considered such.[citation needed] Upon his death, the Yellow Emperor was "said to have become" a xian.[17]

Besides enlightened humans and fairy-like humanoid beings, xiān can also refer to supernatural animals, including foxes, fox spirits,[25] and Chinese dragons.[26][27] Xian dragons were thought to be the mounts of gods and goddesses[27] or manifestations of the spirit of Taoists such as Laozi that existed in a mental realm sometimes called "the Heavens".[26]

The mythological húlijīng 狐狸精 (lit. "fox spirit") "fox fairy; vixen; witch; enchantress" has an alternate name of húxiān 狐仙 (lit. "fox immortal").

The etymology of xiān remains uncertain. The circa 200 CE Shiming, a Chinese dictionary that provided word-pun "etymologies", defines xiān (仙) as "to get old and not die," and explains it as someone who qiān (遷 "moves into") the mountains."

Its writing is a combination of 人 (pinyin: rén; lit. 'human') and 山 (pinyin: shān; lit. 'mountain'). Its historical form is 僊: a combination of 人 (pinyin: rén; lit. 'human') and 遷/䙴 (pinyin: qiān; lit. 'moving into').

Edward H. Schafer[28] defined xian as "transcendent, sylph (a being who, through alchemical, gymnastic and other disciplines, has achieved a refined and perhaps immortal body, able to fly like a bird beyond the trammels of the base material world into the realms of aether, and nourish himself on air and dew.)" Schafer noted xian was cognate to xian 䙴 "soar up", qian 遷 "remove", and xianxian 僊僊 "a flapping dance movement"; and compared Chinese yuren 羽人 "feathered man; xian" with English peri "a fairy or supernatural being in Persian mythology" (Persian pari from par "feather; wing").

Two linguistic hypotheses for the etymology of xian involve Arabic and Sino-Tibetan languages. Wu and Davis suggested the source was jinn, or jinni "genie" (from Arabic جني jinnī).[29] "The marvelous powers of the Hsien are so like those of the jinni of the Arabian Nights that one wonders whether the Arabic word, jinn, may not be derived from the Chinese Hsien." Axel Schuessler's etymological dictionary[30] suggests a Sino-Tibetan connection between xiān (Old Chinese *san or *sen) "'An immortal' ... men and women who attain supernatural abilities; after death they become immortals and deities who can fly through the air" and Classical Tibetan gšen < g-syen "shaman, one who has supernatural abilities, incl[uding] travel through the air".

The Quanzhen School of Daoism had a variety of definitions about what xian means during its history, including a metaphorical meaning where the term simply means a good, principled person.[31]

The character and its variants

The word xiān is written with three characters 僊, 仙, or 仚, which combine the logographic "radical" rén (人 or 亻 "person; human") with two "phonetic" elements (see Chinese character classification). The oldest recorded xiān character 僊 has a xiān ("rise up; ascend") phonetic supposedly because immortals could "ascend into the heavens". (Compare qiān 遷 "move; transfer; change" combining this phonetic and the motion radical.) The usual modern xiān character 仙, and its rare variant 仚, have a shān (山 "mountain") phonetic. For a character analysis, Schipper interprets "'the human being of the mountain,' or alternatively, 'human mountain'.[32] The two explanations are appropriate to these beings: they haunt the holy mountains, while also embodying nature."

The Classic of Poetry (220/3) contains the oldest occurrence of the character 僊, reduplicated as xiānxiān (僊僊 "dance lightly; hop about; jump around"), and rhymed with qiān (遷). "But when they have drunk too much, Their deportment becomes light and frivolous—They leave their seats, and [遷] go elsewhere, They keep [僊僊] dancing and capering." (tr. James Legge)[33] Needham and Wang suggest xian was cognate with wu 巫 "shamanic" dancing.[34] Paper writes, "the function of the term xian in a line describing dancing may be to denote the height of the leaps. Since, "to live for a long time" has no etymological relation to xian, it may be a later accretion."[35]

The 121 CE Shuowen Jiezi, the first important dictionary of Chinese characters, does not enter 仙 except in the definition for 偓佺 (Wòquán "name of an ancient immortal"). It defines 僊 as "live long and move away" and 仚 as "appearance of a person on a mountaintop".

Textual references

This section chronologically reviews how Chinese texts describe xian "immortals; transcendents". Early text such as Zhuangzi, Chuci, and Liezi texts allegorically used xian immortals and magic islands to describe spiritual immortality, sometimes using the word yuren 羽人 or "feathered person" (later another word for "Daoist"[Notes 1] ), and were described with motifs of feathers and flying.[36] [37]

Later texts like the Shenxian zhuan and Baopuzi took immortality literally and described esoteric Chinese alchemical techniques for physical longevity, with techniques such as neidan ("internal alchemy") and waidan ("external alchemy"). Neidan techniques included taixi ("embryonic respiration") breath control, meditation, visualization, sexual training, and daoyin exercises (which later evolved into qigong and tai chi), while waidan techniques for immortality included alchemical recipes, magic plants, rare minerals, herbal medicines, drugs, and dietetic techniques like inedia.

Besides the following major Chinese texts, many others use both graphic variants of xian. Xian (仙) occurs in the Chunqiu Fanlu, Fengsu Tongyi, Qian fu lun, Fayan, and Shenjian; xian occurs in the Caizhong langji, Fengsu Tongyi, Guanzi, and Shenjian.

They are usually found in Taoist texts, although some Buddhist sources mention them. Chinese folk religion and writings on it also use them, such as in Northeast China with the fox gods or "huxian" common in the region.

The Three Sovereigns had similarities to xian because of some of their supernatural abilities and could have been considered such.[citation needed] Upon his death, the Yellow Emperor was "said to have become" a xian.[17]

During the Six Dynasties, xian were a common subject of zhiguai stories.[38] They often had "magical" Tao powers including the abilities to "walk...through walls or stand...in light without casting a shadow."[38]

Zhuangzi

Two circa 3rd century BCE "Outer Chapters" of the Zhuangzi ("[Book of] Master Zhuang") use the archaic character xian (僊). Chapter 11 has a parable about "Cloud Chief" (雲 將) and "Big Concealment" (鴻濛) that uses the Shijing compound xianxian ("dance; jump"):

Big Concealment said, "If you confuse the constant strands of Heaven and violate the true form of things, then Dark Heaven will reach no fulfillment. Instead, the beasts will scatter from their herds, the birds will cry all night, disaster will come to the grass and trees, misfortune will reach even to the insects. Ah, this is the fault of men who 'govern'!"

"Then what should I do?" said Cloud Chief.

"Ah," said Big Concealment, "you are too far gone! [僊僊] Up, up, stir yourself and be off!"

Cloud Chief said, "Heavenly Master, it has been hard indeed for me to meet with you—I beg one word of instruction!"

"Well, then—mind‑nourishment!" said Big Concealment. "You have only to rest in inaction and things will transform themselves. Smash your form and body, spit out hearing and eyesight, forget you are a thing among other things, and you may join in great unity with the deep and boundless. Undo the mind, slough off spirit, be blank and soulless, and the ten thousand things one by one will return to the root—return to the root and not know why. Dark and undifferentiated chaos—to the end of life none will depart from it. But if you try to know it, you have already departed from it. Do not ask what its name is, do not try to observe its form. Things will live naturally end of themselves."

Cloud Chief said, "The Heavenly Master has favored me with this Virtue, instructed me in this Silence. All my life I have been looking for it, and now at last I have it!" He bowed his head twice, stood up, took his leave, and went away. (11)[39]

Chapter 12 uses xian when mythical Emperor Yao describes a shengren (聖 人 "sagely person").

The true sage is a quail at rest, a little fledgling at its meal, a bird in flight who leaves no trail behind. When the world has the Way, he joins in the chorus with all other things. When the world is without the Way, he nurses his Virtue and retires in leisure. And after a thousand years, should he weary of the world, he will leave it and [上] ascend to [僊] the immortals, riding on those white clouds all the way up to the village of God. (12)[40]

Without using the word xian, several Zhuangzi passages employ xian imagery, like flying in the clouds, to describe individuals with superhuman powers. For example, Chapter 1, within the circa 3rd century BCE "Inner Chapters", has two portrayals. First is this description of Liezi (below).

Lieh Tzu could ride the wind and go soaring around with cool and breezy skill, but after fifteen days he came back to earth. As far as the search for good fortune went, he didn't fret and worry. He escaped the trouble of walking, but he still had to depend on something to get around. If he had only mounted on the truth of Heaven and Earth, ridden the changes of the six breaths, and thus wandered through the boundless, then what would he have had to depend on? Therefore, I say, the Perfect Man has no self; the Holy Man has no merit; the Sage has no fame. (1)[41]

Second is this description of a shenren (神人; "divine person").

He said that there is a Holy Man living on faraway [姑射] Ku-she Mountain, with skin like ice or snow, and gentle and shy like a young girl. He doesn't eat the five grains, but sucks the wind, drinks the dew, climbs up on the clouds and mist, rides a flying dragon, and wanders beyond the Four Seas. By concentrating his spirit, he can protect creatures from sickness and plague and make the harvest plentiful. (1)[42]

The authors of the Zhuangzi had a lyrical view of life and death, seeing them as complementary aspects of natural changes. This is antithetical to the physical immortality (changshengbulao 長生不老 "live forever and never age") sought by later Daoist alchemists. Consider this famous passage about accepting death.

Chuang Tzu's wife died. When Hui Tzu went to convey his condolences, he found Chuang Tzu sitting with his legs sprawled out, pounding on a tub and singing. "You lived with her, she brought up your children and grew old," said Hui Tzu. "It should be enough simply not to weep at her death. But pounding on a tub and singing—this is going too far, isn't it?" Chuang Tzu said, "You're wrong. When she first died, do you think I didn't grieve like anyone else? But I looked back to her beginning and the time before she was born. Not only the time before she was born, but the time before she had a body. Not only the time before she had a body, but the time before she had a spirit. In the midst of the jumble of wonder and mystery a change took place and she had a spirit. Another change and she had a body. Another change and she was born. Now there's been another change and she's dead. It's just like the progression of the four seasons, spring, summer, fall, winter."

"Now she's going to lie down peacefully in a vast room. If I were to follow after her bawling and sobbing, it would show that I don't understand anything about fate. So I stopped. (18)[43]

Alan Fox explains this anecdote about Zhuangzi's wife.

Many conclusions can be reached on the basis of this story, but it seems that death is regarded as a natural part of the ebb and flow of transformations which constitute the movement of Dao. To grieve over death, or to fear one's own death, for that matter, is to arbitrarily evaluate what is inevitable. Of course, this reading is somewhat ironic given the fact that much of the subsequent Daoist tradition comes to seek longevity and immortality, and bases some of their basic models on the Zhuangzi.[44]

Chuci

The 3rd–2nd century BCE Chuci ("Lyrics of Chu") anthology of poems uses xian 仙 once and xian 僊 twice, reflecting the disparate origins of the text. These three contexts mention the legendary Daoist xian immortals Chi Song (赤松 "Red Pine",[45] and Wang Qiao (王僑, or Zi Qiao 子僑). In later Daoist hagiography, Chi Song was Lord of Rain under Shennong, the legendary inventor of agriculture; and Wang Qiao was a son of King Ling of Zhou (r. 571–545 BCE), who flew away on a giant white bird, became an immortal and was never again seen.

Yuan You

The "Yuan You" ("Far-off Journey") poem describes a spiritual journey into the realms of gods and immortals, frequently referring to Daoist myths and techniques.

My spirit darted forth and did not return to me,

And my body, left tenantless, grew withered and lifeless.

Then I looked into myself to strengthen my resolution,

And sought to learn from where the primal spirit issues.

In emptiness and silence I found serenity;

In tranquil inaction I gained true satisfaction.

I heard how once Red Pine had washed the world's dust off:

I would model myself on the pattern he had left me.

I honoured the wondrous powers of the [真人] Pure Ones,

And those of past ages who had become [仙] Immortals.

They departed in the flux of change and vanished from men's sight,

Leaving a famous name that endures after them.[46]

Xi shi

The "Xi shi" ("Sorrow for Troth Betrayed") resembles the "Yuan You", and both reflect Daoist ideas from the Han period. "Though unoriginal in theme," says Hawkes, "its description of air travel, written in a pre-aeroplane age, is exhilarating and rather impressive."[47]

We gazed down of the Middle Land [China] with its myriad people

As we rested on the whirlwind, drifting about at random.

In this way we came at last to the moor of Shao-yuan:

There, with the other blessed ones, were Red Pine and Wang Qiao.

The two Masters held zithers tuned in perfect concord:

I sang the Qing Shang air to their playing.

In tranquil calm and quiet enjoyment,

Gently I floated, inhaling all the essences.

But then I thought that this immortal life of [僊] the blessed,

Was not worth the sacrifice of my home-returning.[48]

Ai shi ming

The "Ai shi ming" ("Alas That My Lot Was Not Cast") describes a celestial journey similar to the previous two.

Far and forlorn, with no hope of return:

Sadly I gaze in the distance, over the empty plain.

Below, I fish in the valley streamlet;

Above, I seek out [僊] holy hermits.

I enter into friendship with Red Pine;

I join Wang Qiao as his companion. We send the Xiao Yang in front to guide us;

The White Tiger runs back and forth in attendance.

Floating on the cloud and mist, we enter the dim height of heaven;

Riding on the white deer we sport and take our pleasure.[49]

Li Sao

The "Li Sao" ("On Encountering Trouble"), the most famous Chuci poem, is usually interpreted as describing ecstatic flights and trance techniques of Chinese shamans. The above three poems are variations describing Daoist xian.

Some other Chuci poems refer to immortals with synonyms of xian. For instance, "Shou zhi" (守志 "Maintaining Resolution), uses zhenren (真人 "true person", tr. "Pure Ones" above in "Yuan You"), which Wang Yi's commentary glosses as zhen xianren (真仙人 "true immortal person").

I visited Fu Yue, bestriding a dragon,

Joined in marriage with the Weaving Maiden,

Lifted up Heaven's Net to capture evil,

Drew the Bow of Heaven to shoot at wickedness,

Followed the [真人] Immortals fluttering through the sky,

Ate of the Primal Essence to prolong my life.[50]

Han dynasty xian texts

In at least the latter two centuries of the Han dynasty, the idea of becoming a xian received more popularity than in previous eras of Chinese religion.[51]

In ancient Chinese dynasties such as the Han, various gods were thought to be xian instead in some retellings of their mythology. Hou Yi was one example of this.[52]

Liezi

The Liezi ("[Book of] Master Lie"), which Louis Komjathy says[53] "was probably compiled in the 3rd century CE (while containing earlier textual layers)", uses xian four times, always in the compound xiansheng (仙聖 "immortal sage").

Nearly half of Chapter 2 ("The Yellow Emperor") comes from the Zhuangzi, including this recounting of the above fable about Mount Gushe (姑射, or Guye, or Miao Gushe 藐姑射).

The Ku-ye mountains stand on a chain of islands where the Yellow River enters the sea. Upon the mountains there lives a Divine Man, who inhales the wind and drinks the dew, and does not eat the five grains. His mind is like a bottomless spring, his body is like a virgin's. He knows neither intimacy nor love, yet [仙聖] immortals and sages serve him as ministers. He inspires no awe, he is never angry, yet the eager and diligent act as his messengers. He is without kindness and bounty, but others have enough by themselves; he does not store and save, but he himself never lacks. The Yin and Yang are always in tune, the sun and moon always shine, the four seasons are always regular, wind and rain are always temperate, breeding is always timely, the harvest is always rich, and there are no plagues to ravage the land, no early deaths to afflict men, animals have no diseases, and ghosts have no uncanny echoes.[54]

Chapter 5 uses xiansheng three times in a conversation set between legendary rulers Tang (湯) of the Shang dynasty and Ji (革) of the Xia dynasty.

T'ang asked again: 'Are there large things and small, long and short, similar and different?'

—'To the East of the Gulf of Chih-li, who knows how many thousands and millions of miles, there is a deep ravine, a valley truly without bottom; and its bottomless underneath is named "The Entry to the Void". The waters of the eight corners and the nine regions, the stream of the Milky Way, all pour into it, but it neither shrinks nor grows. Within it there are five mountains, called Tai-yü, Yüan-chiao, Fang-hu, Ying-chou and P'eng-Iai. These mountains are thirty thousand miles high, and as many miles round; the tablelands on their summits extend for nine thousand miles. It is seventy thousand miles from one mountain to the next, but they are considered close neighbours. The towers and terraces upon them are all gold and jade, the beasts and birds are all unsullied white; trees of pearl and garnet always grow densely, flowering and bearing fruit which is always luscious, and those who eat of it never grow old and die. The men who dwell there are all of the race of [仙聖] immortal sages, who fly, too many to be counted, to and from one mountain to another in a day and a night. Yet the bases of the five mountains used to rest on nothing; they were always rising and falling, going and returning, with the ebb and flow of the tide, and never for a moment stood firm. The [仙聖] immortals found this troublesome, and complained about it to God. God was afraid that they would drift to the far West and he would lose the home of his sages. So he commanded Yü-ch'iang to make fifteen [鼇] giant turtles carry the five mountains on their lifted heads, taking turns in three watches, each sixty thousand years long; and for the first time the mountains stood firm and did not move.

'But there was a giant from the kingdom of the Dragon Earl, who came to the place of the five mountains in no more than a few strides. In one throw he hooked six of the turtles in a bunch, hurried back to his country carrying them together on his back, and scorched their bones to tell fortunes by the cracks. Thereupon two of the mountains, Tai-yü and Yüan-chiao, drifted to the far North and sank in the great sea; the [仙聖] immortals who were carried away numbered many millions. God was very angry, and reduced by degrees the size of the Dragon Earl's kingdom and the height of his subjects. At the time of Fu-hsi and Shen-nung, the people of this country were still several hundred feet high.'[55]

Penglai Mountain became the most famous of these five mythical peaks where the elixir of life supposedly grew, and is known as Horai in Japanese legends. The first emperor Qin Shi Huang sent his court alchemist Xu Fu on expeditions to find these plants of immortality, but he never returned (although by some accounts, he discovered Japan).

Holmes Welch analyzed the beginnings of Daoism, sometime around the 4th–3rd centuries BCE, from four separate streams: philosophical Daoism (Laozi, Zhuangzi, Liezi), a "hygiene school" that cultivated longevity through breathing exercises and yoga, Chinese alchemy and Five Elements philosophy, and those who sought Penglai and elixirs of "immortality".[56] This is what he concludes about xian.

It is my own opinion, therefore, that though the word hsien, or Immortal, is used by Chuang Tzu and Lieh Tzu, and though they attributed to their idealized individual the magic powers that were attributed to the hsien in later times, nonetheless the hsien ideal was something they did not believe in—either that it was possible or that it was good. The magic powers are allegories and hyperboles for the natural powers that come from identification with Tao. Spiritualized Man, P'eng-lai, and the rest are features of a genre which is meant to entertain, disturb, and exalt us, not to be taken as literal hagiography. Then and later, the philosophical Taoists were distinguished from all other schools of Taoism by their rejection of the pursuit of immortality. As we shall see, their books came to be adopted as scriptural authority by those who did practice magic and seek to become immortal. But it was their misunderstanding of philosophical Taoism that was the reason they adopted it.[57]

Shenxian zhuan

The Shenxian zhuan (神仙傳 Biographies of Spirit Immortals") is a hagiography of xian. Although it was traditionally attributed to Ge Hong (283–343 CE), Komjathy says,[58] "The received versions of the text contain some 100-odd hagiographies, most of which date from 6th–8th centuries at the earliest."

According to the Shenxian zhuan, there are four schools of immortality:

Qi (气—"energy"): Breath control and meditation. Those who belong to this school can

"...blow on water and it will flow against its own current for several paces; blow on fire, and it will be extinguished; blow at tigers or wolves, and they will crouch down and not be able to move; blow at serpents, and they will coil up and be unable to flee. If someone is wounded by a weapon, blow on the wound, and the bleeding will stop. If you hear of someone who has suffered a poisonous insect bite, even if you are not in his presence, you can, from a distance, blow and say in incantation over your own hand (males on the left hand, females on the right), and the person will at once be healed even if more than a hundred li away. And if you yourself are struck by a sudden illness, you have merely to swallow pneumas in three series of nine, and you will immediately recover.

But the most essential thing [among such arts] is fetal breathing. Those who obtain [the technique of] fetal breathing become able to breathe without using their nose or mouth, as if in the womb, and this is the culmination of the way [of pneumatic cultivation]."[59]

Fàn (饭—"Diet"): Ingestion of herbal compounds and abstention from the Sān Shī Fàn (三尸饭—"Three-Corpses food")—Meats (raw fish, pork, dog, leeks, and scallions) and grains. The Shenxian zhuan uses this story to illustrate the importance of bigu "grain avoidance":

"During the reign of Emperor Cheng of the Han, hunters in the Zhongnan Mountains saw a person who wore no clothes, his body covered with black hair. Upon seeing this person, the hunters wanted to pursue and capture him, but the person leapt over gullies and valleys as if in flight, and so could not be overtaken. [But after being surrounded and captured, it was discovered this person was a 200 plus year old woman, who had once been a concubine of Qin Emperor Ziying. When he had surrendered to the 'invaders of the east', she fled into the mountains where she learned to subside on 'the resin and nuts of pines' from an old man. Afterwards, this diet 'enabled [her] to feel neither hunger nor thirst; in winter [she] was not cold, in summer [she] was not hot.']

The hunters took the woman back in. They offered her grain to eat. When she first smelled the stink of grain, she vomited, and only after several days could she tolerate it. After little more than two years of this [diet], her body hair fell out; she turned old and died. Had she not been caught by men, she would have become a transcendent."[60]

Fángzhōng Zhī Shù (房中之术—"Arts of the Bedchamber"): Sexual yoga.[61] According to a discourse between the Yellow Emperor and the immortaless Sùnǚ (素女—"Plain Girl"), one of the three daughters of Hsi Wang Mu,

"The sexual behaviors between a man and woman are identical to how the universe itself came into creation. Like Heaven and Earth, the male and female share a parallel relationship in attaining an immortal existence. They both must learn how to engage and develop their natural sexual instincts and behaviors; otherwise the only result is decay and traumatic discord of their physical lives. However, if they engage in the utmost joys of sensuality and apply the principles of yin and yang to their sexual activity, their health, vigor, and joy of love will bear them the fruits of longevity and immortality.[62]

The White Tigress (Zhuang Li Quan Pure Angelic Metal Ajna Empress "Toppest") Manual, a treatise on female sexual yoga, states,

"A female can completely restore her youthfulness and attain immortality if she refrains from allowing just one or two men in her life from stealing and destroying her [sexual] essence, which will only serve in aging her at a rapid rate and bring about an early death. However, if she can acquire the sexual essence of a thousand males through absorption, she will acquire the great benefits of youthfulness and immortality."[63]

Dān (丹—"Alchemy", literally "Cinnabar"): Elixir of Immortality.[64]

Baopuzi

The 4th century CE Baopuzi (抱朴子 "[Book of] Master Embracing Simplicity"), which was written by Ge Hong, gives some highly detailed descriptions of xian.

The text lists three classes of immortals:

- Tiānxiān (天仙—"Celestial Immortal"): The highest level.

- Dìxiān (地仙—"Earth Immortal"): The middle level.

- Shījiě xiān (尸解仙—"Escaped-by-means-of-a-stimulated-corpse-simulacrum Immortal", literally "Corpse Untie Immortal"): The lowest level. This is considered the lowest form of immortality since a person must first "fake" their own death by substituting a bewitched object like a bamboo pole, sword, talisman or a shoe for their corpse or slipping a type of Death certificate into the coffin of a newly departed paternal grandfather, thus having their name and "allotted life span" deleted from the ledgers kept by the Sīmìng (司命—"Director of allotted life spans", literally "Controller of Fate"). Hagiographies and folktales abound of people who seemingly die in one province, but are seen alive in another. Mortals who choose this route must cut off all ties with family and friends, move to a distant province, and enact the Ling bao tai xuan yin sheng zhi fu (靈寳太玄隂生之符—"Numinous Treasure Talisman of the Grand Mystery for Living in Hiding") to protect themselves from heavenly retribution.[65] However, this is not a true form of immortality. For each misdeed a person commits, the Director of allotted life spans subtracts days and sometimes years from their allotted life span. This method allows a person to live out the entirety of their allotted lifespan (whether it be 30, 80, 400, etc.) and avoid the agents of death. But the body still has to be transformed into an immortal one, hence the phrase Xiānsǐ hòutuō (先死後脱—"The 'death' is apparent, [but] the sloughing off of the body's mortality remains to be done."). Sometimes the Shījiě are employed by heaven to act as celestial peace keepers. Therefore, they have no need for hiding from retribution since they are empowered by heaven to perform their duties. There are three levels of heavenly Shījiě:

- Dìxià zhǔ (地下主—"Agents Beneath the Earth"): Are in charge of keeping the peace within the Chinese underworld. They are eligible for promotion to earthbound immortality after 280 years of faithful service.

- Dìshàng zhǔzhě (地上主者—"Agents Above the Earth"): Are given magic talismans which prolong their lives (but not indefinitely) and allow them to heal the sick and exorcize demons and evil spirits from the earth. This level was not eligible for promotion to earthbound immortality.

- Zhìdì jūn (制地君—"Lords Who Control the Earth"): A heavenly decree ordered them to "disperse all subordinate junior demons, whether high or low [in rank], that have cause afflictions and injury owing to blows or offenses against the Motion of the Year, the Original Destiny, Great Year, the Kings of the Soil or the establishing or breaking influences of the chronograms of the tome. Annihilate them all." This level was also not eligible for promotion to immortality.

These titles were usually given to humans who had either not proven themselves worthy of or were not fated to become immortals. One such famous agent was Fei Changfang, who was eventually murdered by evil spirits because he lost his book of magic talismans. However, some immortals are written to have used this method in order to escape execution.[65]

Ge Hong wrote in his book The Master Who Embraces Simplicity,

The [immortals] Dark Girl and Plain Girl compared sexual activity as the intermingling of fire [yang/male] and water [yin/female], claiming that water and fire can kill people but can also regenerate their life, depending on whether or not they know the correct methods of sexual activity according to their nature. These arts are based on the theory that the more females a man copulates with, the greater benefit he will derive from the act. Men who are ignorant of this art, copulating with only one or two females during their life, will only suffice to bring about their untimely and early death.[63]

Zhong Lü Chuan Dao Ji

The Zhong Lü Chuan Dao Ji (鐘呂傳道集/钟吕传道集 "Anthology of the Transmission of the Dao from Zhong[li Quan] to Lü [Dongbin]") is associated with Zhongli Quan (2nd century CE?) and Lü Dongbin (9th century CE), two of the legendary Eight Immortals. It is part of the so-called "Zhong-Lü" (鍾呂) textual tradition of internal alchemy (neidan). Komjathy describes it as, "Probably dating from the late Tang (618–906), the text is in question-and-answer format, containing a dialogue between Lü and his teacher Zhongli on aspects of alchemical terminology and methods."[66]

The Zhong Lü Chuan Dao Ji lists five classes of immortals:

- Guǐxiān (鬼仙—"Ghost Immortal"): A person who cultivates too much yin energy. These immortals are likened to Vampires because they drain the life essence of the living, much like the fox spirit. Ghost immortals do not leave the realm of ghosts.

- Rénxiān (人仙—Human Immortal"): Humans have an equal balance of yin and yang energies, so they have the potential of becoming either a ghost or immortal. Although they continue to hunger and thirst and require clothing and shelter like a normal human, these immortals do not suffer from aging or sickness. Human immortals do not leave the realm of humans. There are many sub-classes of human immortals, as discussed above under Shījiě xiān.

- Dìxiān (地仙—"Earth Immortal"): When the yin is transformed into the pure yang, a true immortal body will emerge that does not need food, drink, clothing or shelter and is not affected by hot or cold temperatures. Earth immortals do not leave the realm of earth. These immortals are forced to stay on earth until they shed their human form.

- Shénxiān (神仙—"Spirit Immortal"): The immortal body of the earthbound class will eventually change into vapor through further practice. They have supernatural powers and can take on the shape of any object. These immortals must remain on earth acquiring merit by teaching mankind about the Tao. Spirit immortals do not leave the realm of spirits. Once enough merit is accumulated, they are called to heaven by a celestial decree.

- Tiānxiān (天仙—"Celestial Immortal"): Spirit immortals who are summoned to heaven are given the minor office of water realm judge. Over time, they are promoted to oversee the earth realm and finally become administrators of the celestial realm. These immortals have the power to travel back and forth between the earthly and celestial realms.

Śūraṅgama Sūtra

The Śūraṅgama Sūtra, a Mahayana Buddhist manuscript, in a borrowing from Taoist teachings, discusses the characteristics of ten types of xian who exist between the world of devas ("gods") and that of human beings.[19] This position in Buddhist literature is usually occupied by asuras. Xian as portrayed here are of a different and contrasting type of existence in Buddhist cosmology to asuras.[further explanation needed] These xian are not considered true cultivators of samadhi ("unification of mind"), as their methods differ from the practice of dhyāna ("meditation").

- Dìxiān (地(行)仙; Dìxíng xiān, "earth-travelling immortals") – Xian who constantly ingest special food called fuer (服餌).

- Fēixiān (飛(行)仙; Fēixíng xiān, "flying immortals") – Xian who constantly ingest certain herbs and plants.

- Yóuxiān (遊(行)仙; Yóuxíng xiān, "roaming immortals") – Xian who "transform" by constantly ingesting metals and minerals.

- Kōngxiān (空(行)仙; Kōngxíng xiān, "void-travelling immortals") – Xian who perfect their qi and essence through unceasing movement and stillness (dongzhi 動止).

- Tiānxiān (天(行)仙; Tiānxíng xiān, "heaven-travelling immortals") – Xian who constantly practice control of their fluids and saliva.

- Tōngxiān (通(行)仙; Tōngxíng xiān, "all-penetrating immortals") – Xian who constantly practice the inhalation of unadulterated essences.

- Dàoxiān (道(行)仙; Dàoxíng xiān, "immortals of the Way") – Xian who achieve transcendence through unceasing recitation of spells and prohibitions.

- Zhàoxiān (照(行)仙; Zhàoxíng xiān, "illuminated immortals") – Xian who achieve transcendence through constant periods of thought and recollection.

- Jīngxiān (精(行)仙; Jīngxíng xiān, "seminal immortals") – Xian who have mastered the stimuli and responses of intercourse.

- Juéxiān (絕(行)仙; Juéxíng xiān, "absolute immortals") – Xian who "have attained the end" and perfected their awakening through constant transformation.

In religions

Chinese folk religion

Ancient Chinese folk religion believed xian were deceased noblemen, such as emperors and ancestors who were nobles, as well as commoner "worthies".[67] However, Taoism changed that belief eventually by making the Taoist view of a xian as a holy human being, who could be good or evil, who went to heaven by following a path that would make the soul stay in the body permanently, along with making the body disappear from Earth, popular among folk religious practitioners.[67]

In 2005, roughly 8% of Chinese folk practitioners believed in "immortal souls".[68]

Taoism

Taoists sometimes had the same beliefs as folk religious practitioners about noblemen and noble ancestors, although they invented the ideas that said otherwise.[67]

Many Taoists believed that xian were spirits of human origin and that they could become them. It was believed that they could become immortals by refining their bodies throughout their lives by taking drugs and/or performing the correct amount of good deeds and repentant acts to make up for bad deeds throughout their lives.[69] Heaven, and therefore, status as an immortal, was also thought to be accessible through being an unenlightened soul in the afterlife that is prayed for in the collective salvation prayers of Taoist temple worshippers, who pray in the hope that souls will reach a better status in their death.[69]

A form of Taoism that worshipped xian that became popular in roughly the year 50 was called "Hsien...Taoism".[70] This type of Taoism was also associated with worshipping Chinese "household gods" and doing rituals to achieve the status of an immortal xian after death.[70]

In art and culture

According to Michael Loewe, the earliest artistic and textual evidence of xian transcendents dates from the fifth or fourth centuries BCE. They were depicted as avian and serpentine hybrids who could fly through the universe, typically either combinations of a bird's body and a human face, or a human with wings sprouting on their back, i.e., a yuren (羽人, "feathered person").[71]

According to John Lagerway, the earliest artistic representations of xian date from the second century BC.[36]

In tomb reliefs from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE), xian are often bird-human and reptile-human hybrids, depicted as "liminal but spiritually empowered figures" who accompanied a deceased person's soul to paradise, "transient figures moving through an intermediate realm" where they are often joined by deer, tigers, dragons, birds, heavenly horses (tianma 天馬), and other animals.[72] These avian, serpentine, and human hybrid xian are frequently depicted with "secondary characteristics" including androgyny, large ears, long hair, exaggerated nonhuman faces, tattoo-like markings, and nudity; many of these traits also appear in depictions of foreigners, who also lived outside the Chinese cultural and spiritual sphere.[73]

Xian were and are associated with yin and yang,[70] and some Taoist sects held that the "adept of immortality" could get in touch with the "pure energies [related to yin and yang] possessed at birth by every infant" to become a xian.[74] If a Taoist in these beliefs became a xian, he or she could live for 1,000 years in the human world if he or she chose to, and afterwards, transform his or her body into "pure yang energy and ascend...to [Tiān]".[74]

In modern and historical times, xian are also thought to draw power and be created from the Tao in its aspect as "the source of all being, in which life and death are the same."[75]

Xian are conventionally held to be beings that bring good fortune and "benevolent spirits".[76] Some Taoists beseeched xian, multiple xian, and pantheons of xian to aid them in life[77] and/or abolish their sins.[4]

Refugee communities and their descendants, wanderers, and Taoists who were societal recluses inspired myths of "timeless" worlds where xian lived.[78] In many Taoist sects, xian were thought to "dress...in feathers" and live in the atmosphere "just off-planet" and explore various places in the universe to perform "various actions and miracles."[79] A Confucian cosmology that had immortals in it viewed them as beings of a "heavenly world", which was "above the earthly world" that was distinct "from a dark underworld".[20]

Some mythical xian were worshipped and/or seen as gods or zhenren,[80][36][10][81][14][82] and some real Taoists were thought to become xian if they died after performing certain rituals or living a certain way and gain the ability to explore "heavenly realms".[80][82] These Taoists' spirits after death would be seen as divine entities that were synonymous with xian,[80][36][10][83] and were often referred to by that name.[83]

Becoming a xian was often seen as a heroic "quest" in Taoist mythos to either become as powerful as a god or multiple gods or gain an immortal lifespan like a god.[81] Given that many Taoists believed that their gods and gods belonging to different ethnic groups and other religions were subject to the roles the Tao made for them,[84] becoming a xian is technically a process that lets a practitioner get enough holy or spiritual power to defy that role,[citation needed] and some Taoists chose to worship xian instead of gods,[81][4] it is likely that some Taoists believed that even a single xian was more powerful than entire pantheons of the various gods of China.[citation needed][further explanation needed] Before and during the early Tang dynasty, beliefs about death that included them were notable among ordinary Chinese than Buddhist counterparts, and some who were inclined towards Taoism or were part of a Taoist religious organization and also thought Buddhist deities existed believed xian, collectively, were more powerful and relevant than Buddhist gods.[14]

Some sects thought they were more worthy to venerate than gods because of their admirable qualities or their being more powerful in a only few specific ways, such as comprehension of some heavenly powers and/or the spiritual location they live in, while acknowledging their lack of strength and their typical place in the celestial hierarchy being below gods.[85][4]

In the Han dynasty and Tang dynasty, the ideas of xian and becoming them were quite popular.[16][51] Chinese folk religion practitioners in the Tang dynasty[14] when Chinese religious traditions were more entrenched drew symbols of immortality and paintings with Taoist symbolism on tombs so their family members could have a chance at becoming xian,[16][51] and this happened in the Han dynasty as well[16][51] before some theological ideas that would become popular later on.

In Buddhist-inspired Taoism and Buddhist traditions that venerated Laozi and/or other Taoist icons, a minority of xian on Mount Kunlun and the wider world spoke Sanskrit[3] and/or other foreign languages,[citation needed] as it was seen as a sacred language[3] and possibly because some xian were thought of as spirits of Indian origin or ascended humans from the same area or other parts of the world.[citation needed]

A pseudo-Sanskrit language that was mixed with Chinese and was often random in its structure and mixture of the two called "the sounds of Brahmā-heaven" was also seen as another sacred language used as a liturgical language,[3] and was frequently confused with Sanskrit. It was thought of as an important godly language that a Taoist version of Brahmā spoke and that some immortals also spoke to a lesser degree which was the embodiment of the Tao, "the esoteric sounds of the heavens", "the beginning of the universe", the harmonious relation between the gods (who Brahmā ruled over), and Indian and Buddhist philosophy thought to be transmitted by Laozi.[3]

In Japan, the image of the sennin was perpetuated in many legends and art such as miniature sculptures (netsuke). Below is a wooden netsuke, made in the 18th century. It represents a perplexed old man with one hand based on the curve of a snag, and the other hand is rubbing his head with concern. He is looking somewhere in the sky and tucked up the right leg. This position was commonly used for art of Sennin Tekkay, whose soul has found the second life in the body of the lame beggar. In shape the beggarly old man this legendary personality portrayed prominent carver of the early period Jobun. A similar humorous depiction of xian in China came in the form of Dongfang Shuo, a deified Han dynasty scholar who was thought to be a "clown" xian after death.[82] There were also legends about him in this state in Japan and Korea.[86]

Sennin is a common Japanese character name. For example, Ikkaku Sennin (一角仙人 "One-horned Immortal") was a Noh play by Komparu Zenpō (金春禅鳳, 1454–1520?). The Japanese legend of Gama Sennin (蝦蟇仙人 "Toad Immortal") is based upon Chinese Liu Hai, a fabled 10th-century alchemist who learned the secret of immortality from the Chan Chu ("Three-legged Money Toad").

In Korea among commoners who belonged to no specific religious tradition, the desire to become an immortal, imported from China and Korean Taoist sects, mostly manifested itself in the wish for merely longer life instead of living forever.[87] Peaks and valleys were commonly named after the xian, and Buddhist principles were also sometimes thought to be important to becoming one in Korea and art communities in Korea often approved of paintings of Taoist immortals and others depicting Buddhist symbolism.[87] Xian were sometimes viewed as gods in Korea.[23][88]

Depictions of xians, sennins and tiên in art

-

Lacquered yuren (羽人) figure on a toad stand from the Chu kingdom of the Warring States.

-

A Han dynasty stone-relief of Immortal and a deer rider.

-

An immortal riding a tortoise. A Han dynasty stone-relief rubbing.

-

Feathered Immortals playing Liubo. Han dynasty stone-relief.

-

Xiwangmu Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5, Northern Liang

-

Winged xian flying in the heavens, Dengzhou painted stone-relief, Liu Song dynasty.

-

An immortal riding on a dragon, Dengzhou painted stone-relief, Liu Song dynasty.

-

Two immortals, Dengzhou painted stone-relief, Liu Song dynasty.

-

Mogao Cave no. 257mural of the Nine-colored deer and a deity, Northern Wei dynasty

-

Deity with Yueqin on Mogao Cave no.285 mural, Western Wei Dynasty.

-

Immortal Riding a Dragon by Ma Yuan. Southern Song Dynasty

-

Painting of Xiwangmu meeting with a Chinese regent in the Jade Pond, likely King Mu of Zhou or Emperor Wu of Han, Song dynasty

-

The Immortal Zhang Guolao at Repose, Song dynasty

-

Three Immortals

-

The Daoist immortal Lü Dongbin crossing Lake Dongting, Song dynasty

-

Song dynasty brocade depicting the Moon Goddess Chang'e and Attendants

-

The Daoist Immortal He Xiangu by Zhang Lu, early 16th century

-

Ming Dynasty painting of Li Tieguai

-

Ming Dynasty painting of Lü Dongbin

-

The Daoist Immortal Lü Dongbin, a painting from the Ming dynasty

-

Immortal Lü Dongbin and Willow Deity, by Gu Jianlong, Ming dynasty

-

Xian riding dragons[1]

-

Xiwangmu riding on a phoenix.

-

King Father of the East (東王公)

-

Fei Changfang (费长房).

-

He-He Er Xian as painted by Wang Wen, Ming dynasty

-

Ming dynasty painting of Four Time Guardians (四值功曹)

-

Joseon painting of Taoist Immortals by Kim Hong-do.

-

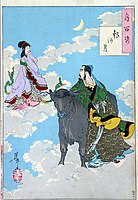

Zhinü and Niulang, by the Japanese painter Tsukioka Yoshitoshi.

-

Sennin with his staff, carver Jobun, 18th century, wood, height 80 mm

-

Lacquer painting of the four tiên, 16th century, Vietnam

-

Lacquer painting of the four tiên, 16th century, Vietnam

-

Tiên water puppet at Vietnam Museum of Ethnology – Hanoi

-

Statues of Tiên, and a Tiên riding a dragon (17th century), Vietnam National Museum of Fine Arts, Hanoi

-

Ceramic statue of Tiên in a museum in Vietnam

-

Ceramic statue of Tiên in a museum in Vietnam

In popular culture

Xian are common characters in Chinese fantasy works. There is a genre called xianxia, which is part of a larger genre called cultivation fantasy or cultivation, named after the beings where characters usually seek to become xian in a fantasy world that is either militaristic or fraught with other dangers.[90]

Example works

- The Legend of Sword and Fairy, video game based on xianxia fiction.

- Lotus Lantern, an animated film based on the story of The Magic Lotus Lantern.

- Heaven Official's Blessing features a story based on the concept of xian and spiritual worship and cultivation.

- Xuanyuan Sword, video game based on xianxia fiction.

- Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain, a 1983 Hong Kong supernatural wuxia fantasy film directed by Tsui Hark and based on the 1932 xianxia novel Legend of the Swordsmen of the Mountains of Shu by Huanzhulouzhu

See also

- Shen (Chinese religion)

- Zhenren

- Eight Immortals

- Eight Immortals from Sichuan

- Fu Lu Shou

- Old Man of the South Pole

- Magu

- Xi Wangmu (Queen Mother of the West)

- Temples of the Five Immortals in China:

- Kunlun Mountain in mythology

- Peaches of Immortality

- Xianxia (genre)

- Sansin

- Yama-no-Kami

- Rishi

- Weizza

- Woodwose

- Yaoguai, a type of ghost that was sometimes thought to be synonymous with the spirits of Taoist immortals

- Zhiguai xiaoshuo, folklore stories where xian are sometimes found

Notes

- ^ Daoist ascension to immortality is also called "羽化登升" or "Becoming feather and ascending"

- ^ Chinese: 仙; pinyin: xiān; Wade–Giles: hsienAncient or variant character forms include 仚 and 僊.

References

- Akahori, Akira. 1989. "Drug Taking and Immortality", in Taoist Meditation and Longevity Techniques, ed. Livia Kohn. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, pp. 73–98. ISBN 0-89264-084-7.

- Blofeld, John. 1978. Taoism: The Road to Immortality. Boston: Shambhala. ISBN 1-57062-589-1.

- Campany, Robert Ford (2002). To Live As Long As Heaven and Earth: Ge Hong's Traditions of Divine Transcendents. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23034-5.

- DeWoskin, Kenneth. 1990. "Xian Descended: Narrating Xian among Mortals." Taoist Resources 1.2:21–27.

- The Book of Lieh-tzǔ: A Classic of Tao. Translated by Graham, A.C. New York City: Columbia University Press. 1990 [1960]. ISBN 0-231-07237-6.

- The Songs of the South: An Anthology of Ancient Chinese Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets. Translated by Hawkes, David. Penguin Books. 1985. ISBN 0-14-044375-4.

- Komjathy, Louis (2004). Daoist texts in translation (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 May 2005. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Loewe, Michael (1978). "Man and Beast: The Hybrid in Early Chinese Art and Literature". Numen. 25 (2): 97–117.

- Robinet, Isabel. 1986. "The Taoist Immortal: Jesters of Light and Shadow, Heaven and Earth". Journal of Chinese Religions 13/14:87–106.

- Wallace, Leslie V. (2001). "BETWIXT AND BETWEEN: Depictions of Immortals (Xian) in Eastern Han Tomb Reliefs". Ars Orientalis. 41: 73–101.

- The Complete works of Chuang Tzu. Translated by Watson, Burton. New York City: Columbia University Press. 1968. ISBN 0-231-03147-5.

- Welch, Holmes (1957). Taoism: The Parting of the Way. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5973-0.

- Wong, Eva. 2000. The Tao of Health, Longevity, and Immortality: The Teachings of Immortals Chung and Lü. Boston: Shambhala.

Footnotes

- ^ a b Werner, E.T.C. (1922). Myths & Legends of China. New York City: George G. Harrap & Co. Available online from Project Gutenberg.

- ^ a b c Dean, Kenneth (1993). Laznovsky, Bill (ed.). Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of Southeast China. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 90, 147–148. ISBN 978-0-691-07417-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Zürcher, Erik (1980). "Buddhist Influence on Early Taoism: A Survey of Scriptural Evidence". T'oung Pao. 66 (1/3): 109. doi:10.1163/156853280X00039. ISSN 0082-5433. JSTOR 4528195 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c d Wilson, Andrew, ed. (1995). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (1st paperback ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-55778-723-1.

- ^ a b c Stevenson, Jay (2000). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Eastern Philosophy. Indianapolis: Alpha Books. pp. 13, 224, 352. ISBN 9780028638201.

- ^ World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 401. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ The Secrets of the Universe in 100 Symbols. New York: Chartwell Books. 2022. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7858-4142-5.

- ^ Clayre, Alasdair (1985). The Heart of the Dragon (First American ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-395-35336-3.

- ^ Helle, Horst J. (2017). "CHAPTER 7 Daoism: China's Native Religion". JSTOR. Brill: 75–76. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h29s.12. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- ^ a b c "zhenren". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson, Philip (1999). Spilling, Michael; Williams, Sophie; Dent, Marion (eds.). Illustrated Dictionary of Religions (First American ed.). New York: DK. pp. 67–68, 70, 121. ISBN 0-7894-4711-8.

- ^ Mair, Victor H. 1994. Wandering on the Way: early Taoist tales and parables of Chuang Tzu. New York: Bantam. p. 376. ISBN 0-553-37406-0.

- ^ Gesterkamp, Lennert (2012). The Heavenly Court Daoist, Temple Painting in China, 1200–1400. Lennert Gesterkamp. ISBN 9789004190238.

- ^ a b c d Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516.

- ^ Smith, Huston (1991). The World's Religions (Revised and Updated ed.). San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-06-250811-9.

- ^ a b c d "Immortality of the Spirit: Chinese Funerary Art from the Han & Tang Dynasties". Fairfield University Art Museum. Fairfield University. 2012. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ a b c "Huangdi". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-05-22.

- ^ Eberhard, Wolfram (2006). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Translated by Campbell, G. L. Routledge. p. 179. ISBN 0-203-03877-0.

- ^ a b Epstein, Ron; Society, Buddhist Text Translation (June 2009). "The Shurangama Sutra Volume Seven" (PDF). Professor Ron Epstein's Online Educational Resources. pp. 197–207. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ a b Scarpari, Maurizio (2006). Ancient China: Chinese Civilization from the Origins to the Tang Dynasty. Translated by Milan, A.B.A. New York: Barnes & Noble. pp. 63, 88, 97, 99, 101, 172, 197. ISBN 978-0-7607-8379-5.

- ^ Bradeen, Ryan; Johnson, Jean (Fall 2005). "Using Monkey to Teach Religions of China" (PDF). Education About Asia. 10 (2). Columbia University: 40–41.

- ^ Stevens, Keith (1997). Chinese Gods: The Unseen World of Spirits and Demons. London: Collins and Brown. pp. 53, 66, 70. ISBN 978-1-85028-409-3.

- ^ a b "각세도(覺世道)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ "성도교(性道敎)". Encyclopedia of Korean Culture (in Korean). Retrieved 2023-06-25.

- ^ Carlson, Kathie; Flanagin, Michael N.; Martin, Kathleen; Martin, Mary E.; Mendelsohn, John; Rodgers, Priscilla Young; Ronnberg, Ami; Salman, Sherry; Wesley, Deborah A.; et al. (Authors) (2010). Arm, Karen; Ueda, Kako; Thulin, Anne; Langerak, Allison; Kiley, Timothy Gus; Wolff, Mary (eds.). The Book of Symbols: Reflections on Archetypal Images. Köln: Taschen. p. 280. ISBN 978-3-8365-1448-4.

- ^ a b Minford, John (2018). Tao Te Ching: The Essential Translation of the Ancient Chinese Book of the Tao. New York: Viking Press. pp. ix–x. ISBN 978-0-670-02498-8.

- ^ a b Sanders, Tao Tao Liu (1980). Dragons, Gods & Spirits from Chinese Mythology. New York: Peter Bedrick Books. p. 73. ISBN 0-87226-922-1.

- ^ Schafer, Edward H. (1966), "Thoughts about a Students' Dictionary of Classical Chinese," Monumenta Serica 25: 197–206. p. 204.

- ^ Wu Lu-ch'iang and Tenney L. Davis. 1935. "An Ancient Chinese Alchemical Classic. Ko Hung on the Gold Medicine and on the Yellow and the White", Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 70:221–284. p. 224.

- ^ Schuessler, Axel. 2007. ABC Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 527. ISBN 0-8248-1111-9.

- ^ Palmer, Martin (1999). The Elements of Taoism. United States: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 89. ISBN 0-7607-1078-3.

- ^ Schipper, Kristofer. 1993. The Taoist Body. Berkeley: University of California. p. 164. ISBN 0-520-08224-9.

- ^ "Shi Jing – Le Canon des Poèmes – II.7.(220)". Association Française des Professeurs de Chinois. Translated by James Legge. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling (1956). "History of Scientific Thought". Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 2. Cambridge University Press. p. 134.

- ^ Paper, Jordan D. 1995. The Spirits Are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese Religion. State University of New York Press. p. 55.

- ^ a b c d Lagerwey, John (2018-05-21). "Xian". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ (圖仙人之形,體生毛,臂變為翼,行於雲,則年增矣,千歲不死。)("In representing the bodies of [xian] one gives them a plumage, and their arms are changed into wings with which they poise in the clouds. This means an extension of their lifetime. They are believed not to die for a thousand years. ")Lunheng; "vol. 7" "chapter 27"p. 27 of 118

- ^ a b Gershon, Livia (2022-02-22). "The Trouble with Immortality". JSTOR Daily. JSTOR. Retrieved 2023-05-27.

- ^ Watson 1968, pp. 122–3.

- ^ Watson 1968, p. 130.

- ^ Watson 1968, p. 32.

- ^ Watson 1968, p. 33.

- ^ Watson 1968, pp. 191–2.

- ^ Fox, Alan. Zhuangzi, in Great Thinkers of the Eastern World, Ian P. McGreal ed., HarperCollins Publishers, 1995, 99–103. p. 100.

- ^ Kohn, Livia. 1993. The Taoist Experience: an anthology. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 142–4. ISBN 0-7914-1579-1.

- ^ Hawkes 1985, p. 194.

- ^ Hawkes 1985, p. 239.

- ^ Hawkes 1985, p. 240.

- ^ Hawkes 1985, p. 266.

- ^ Hawkes 1985, p. 318.

- ^ a b c d Pang, Mae Anna (2013-01-30). "In search of immortality: provisions for the afterlife". Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria. 50 (11). National Gallery of Victoria.

- ^ Ni, Xueting C. (2023). Chinese Myths: From Cosmology and Folklore to Gods and Immortals. London: Amber Books. p. 132. ISBN 978-1-83886-263-3.

- ^ Komjathy 2004, p. 36.

- ^ Graham 1960, p. 35.

- ^ Graham 1960, pp. 97–8.

- ^ Welch 1957, pp. 88–97.

- ^ Welch 1957, p. 95.

- ^ Komjathy 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Campany 2002, p. 21.

- ^ Campany 2002, pp. 22–3.

- ^ Campany 2002, pp. 30–1.

- ^ Hsi, Lai. 2002. The Sexual Teachings of the Jade Dragon: Taoist Methods for Male Sexual Revitalization. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books. pp. 99–100. ISBN 0-89281-963-4.

- ^ a b Hsi, Lai (2001). The Sexual Teachings of the White Tigress: Secrets of the Female Taoist Masters. Rochester, Vermont: Destiny Books. p. 48. ISBN 0-89281-868-9.

- ^ Campany 2002, p. 31.

- ^ a b Campany 2002, pp. 52–60.

- ^ Komjathy 2004, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Helle, Horst J. (2017). "CHAPTER 7 Daoism: China's Native Religion". JSTOR. Brill: 75–76. JSTOR 10.1163/j.ctt1w8h29s.12. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- ^ "Religion in China on the Eve of the 2008 Beijing Olympics". Pew Research Center. 2008-05-01. Retrieved 2023-06-19.

- ^ a b Stark, Rodney (2007). Discovering God: The Origins of the Great Religions and the Evolution of Belief (1st ed.). New York: HarperOne. pp. 258–259, 261–262. ISBN 978-0-06-117389-9.

- ^ a b c Black, Jeremy; Brewer, Paul; Shaw, Anthony; Chandler, Malcolm; Cheshire, Gerard; Cranfield, Ingrid; Ralph Lewis, Brenda; Sutherland, Joe; Vint, Robert (2003). World History. Bath, Somerset: Parragon Books. pp. 39, 343. ISBN 0-75258-227-5.

- ^ Loewe 1978, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Wallace 2001, pp. 1.

- ^ Wallace 2001, p. 79.

- ^ a b Carrasco, David; Warmind, Morten; Hawley, John Stratton; Reynolds, Frank; Giarardot, Norman; Neusner, Jacob; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Campo, Juan; Penner, Hans; et al. (Authors) (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Edited by Wendy Doniger. United States: Merriam-Webster. p. 1065. ISBN 9780877790440.

- ^ Wright, Edmund, ed. (2006). The Desk Encyclopedia of World History. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 365. ISBN 978-0-7394-7809-7.

- ^ "Hsien". Collins. Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Haw, Stephen G. (1998). A Traveller's History of China. Preface by Denis Judd (First American ed.). Brooklyn: Interlink Books. p. 89. ISBN 1-56656-257-0.

- ^ Cleary, Thomas F. (1998). The Essential Tao: An Initiation Into the Heart of Taoism Through the Authentic Tao Te Ching and the Inner Teachings of Chuang-Tzu. Edison, New Jersey: Castle Books. pp. 123–124. ISBN 0-7858-0905-8. OCLC 39243466.

- ^ Forty, Jo (2004). Mythology: A Visual Encyclopedia. London: Barnes & Noble Books. p. 200. ISBN 0-7607-5518-3.

- ^ a b c "xian". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ a b c World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 392. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b c Robinet

- ^ a b World Religions: Eastern Traditions. Edited by Willard Gurdon Oxtoby (2nd ed.). Don Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. 2002. p. 395. ISBN 0-19-541521-3. OCLC 46661540.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Harari, Yuval Noah (2015). Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Translated by Harari, Yuval Noah; Purcell, John; Watzman, Haim. London: Penguin Random House UK. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-09-959008-8. OCLC 910498369.

- ^ Carrasco, David; Warmind, Morten; Hawley, John Stratton; Reynolds, Frank; Giarardot, Norman; Neusner, Jacob; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Campo, Juan; Penner, Hans; et al. (Authors) (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Edited by Wendy Doniger. United States: Merriam-Webster. p. 1067. ISBN 9780877790440.

- ^ Vos, Frits (1979). "Tung-fang Shuo, Buffoon and Immortal, in Japan and Korea". Oriens Extremus. 26 (1/2): 189–203. ISSN 0030-5197. JSTOR 43383385.

- ^ a b A Handbook of Korea (9th ed.). Seoul: Korean Overseas Culture and Information Service. December 1993. pp. 133, 197. ISBN 978-1-56591-022-5.

- ^ Amore, Roy C.; Hussain, Amir; Narayanan, Vasudha; Singh, Pashaura; Vallely, Anne; Woo, Terry Tak-ling; Nelson, John K. (2010). Oxtoby, Willard Gurdon; Amore, Roy C. (eds.). World Religions: Eastern Traditions (3rd ed.). Donn Mills, Ontario: Oxford University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-19-542676-2.

- ^ "《原神》小剧场——「璃月雅集」第五期". bilibili (in Simplified Chinese). 2022-07-27. Archived from the original on 2022-07-28. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- ^ Ni, Zhange (2020-01-02). "Xiuzhen (Immortality Cultivation) Fantasy: Science, Religion, and the Novels of Magic/Superstition in Contemporary China". Religions. 11 (1): 25. doi:10.3390/rel11010025. hdl:10919/96386.

External links

- "Transcendence and Immortality", Russell Kirkland, The Encyclopedia of Taoism

- Chapter Seven: Later Daoism, Gregory Smits, Topics in Premodern Chinese History

- Xian, Encyclopedia of Religion

![Winged xian flying in the heavens, Dengzhou painted stone-relief [zh], Liu Song dynasty.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_17.jpg/200px-Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_17.jpg)

![An immortal riding on a dragon, Dengzhou painted stone-relief [zh], Liu Song dynasty.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/11/Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_07.jpg/200px-Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_07.jpg)

![Two immortals, Dengzhou painted stone-relief [zh], Liu Song dynasty.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d0/Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_08.jpg/200px-Southern_Dynasties_Brick_Relief_08.jpg)

![Xian riding dragons[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0f/Dragon_gods_-_Project_Gutenberg_eText_15250.jpg/136px-Dragon_gods_-_Project_Gutenberg_eText_15250.jpg)