Sphinx

| |

| Grouping | Legendary creatures |

|---|---|

| Similar entities | Griffin, Manticore, Cherub, Lamassu, Narasimha |

| Region | Persian, Egyptian and Greek |

A sphinx (/ˈsfɪŋks/ SFINKS, Template:Lang-grc, Greek: [spʰíŋks]; Boeotian: φίξ, Greek: [pʰíːks]; pl.: sphinxes or sphinges) is a mythical creature with the head of a human, the body of a lion, and the wings of an eagle.

In Greek tradition, the sphinx is a treacherous and merciless being with the head of a woman, the haunches of a lion, and the wings of a bird. According to Greek myth, she challenges those who encounter her to answer a riddle, and kills and eats them when they fail to do so.[1] This deadly version of a sphinx appears in the myth and drama of Oedipus.[2]

In Egyptian mythology, in contrast, the sphinx is typically depicted as a man (an androsphinx (Template:Lang-grc)), and were seen as a benevolent representation of strength and ferocity, usually of a pharaoh. Unlike Greek or Levantine/Mesopotamian ones, Egyptian sphinxes were not winged.

Both the Greek and Egyptian sphinxes were thought of as guardians, and statues of them often flank the entrances to temples.[3] During the Renaissance the sphinx enjoyed a major revival in European decorative art. During this period, images of the sphinx were initially similar to the ancient Egyptian version, but when later exported to other cultures, the sphinx was often conceived of quite differently, partly due to varied translations of descriptions of the originals, and partly through the evolution of the concept as it was integrated into other cultural traditions.

However, depictions of the sphinx are generally associated with grand architectural structures, such as royal tombs or religious temples.

Etymology

The word sphinx comes from the Greek Σφίγξ, associated by folk etymology with the verb σφίγγω (sphíngō), meaning "to squeeze", "to tighten up".[4][5] This name may be derived from the fact that lions kill their prey by strangulation, biting the throat of prey and holding them down until they die. However, the historian Susan Wise Bauer suggests that the word "sphinx" was instead a Greek corruption of the Egyptian name "shesepankh", which meant "living image", and referred rather to the statue of the sphinx, which was carved out of "living rock" (rock that was a contiguous part of the stony body of the Earth, shaped, but not cut away from its original source), than to the beast itself.[6]

Egypt

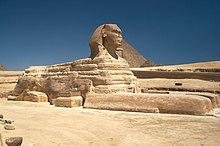

The largest and most famous sphinx is the Great Sphinx of Giza, situated on the Giza Plateau adjacent to the Great Pyramids of Giza on the west bank of the Nile River and facing east (29°58′31″N 31°08′15″E / 29.97528°N 31.13750°E). The sphinx is located southeast of the pyramids. While the date of its construction is not known for certain, the general consensus among Egyptologists is that the head of the Great Sphinx bears the likeness of the pharaoh Khafre, dating it to between 2600 and 2500 BC. However, a fringe minority of late 20th century geologists have claimed evidence of water erosion in and around the Sphinx enclosure which would prove that the Sphinx predates Khafre, at around 10,000 to 5000 BC, a claim that is sometimes referred to as the Sphinx water erosion hypothesis but which has little support among Egyptologists and contradicts other evidence.[7]

What names their builders gave to these statues is not known. At the Great Sphinx site, a 1400 BC inscription on a stele belonging to the 18th dynasty pharaoh Thutmose IV lists the names of three aspects of the local sun deity of that period, Khepera–Rê–Atum. Many pharaohs had their heads carved atop the guardian statues for their tombs to show their close relationship with the powerful solar deity Sekhmet, a lioness. Besides the Great Sphinx, other famous Egyptian sphinxes include one bearing the head of the pharaoh Hatshepsut, with her likeness carved in granite, which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the alabaster Sphinx of Memphis, currently located within the open-air museum at that site. The theme was expanded to form great avenues of guardian sphinxes lining the approaches to tombs and temples as well as serving as details atop the posts of flights of stairs to very grand complexes. Nine hundred sphinxes with ram heads (Criosphinxes), believed to represent Amon, were built in Thebes, where his cult was strongest. At Karnak, each Criosphinx is fronted by a full-length statue of the pharaoh. The task of these sphinxes was to hold back the forces of evil.[8]

The Great Sphinx has become an emblem of Egypt, frequently appearing on its stamps, coins, and official documents.[9]

In March 2023, a limestone sphinx was discovered at the Dendera Temple Complex. This sphinx, which is depicted with a slight grin and dimples, is thought to be made in the image of the Roman emperor Claudius.[10]

Europe

The revived Mannerist sphinx of the late 15th century is sometimes thought of as the "French sphinx". Her coiffed head is erect and she has the breasts of a young woman. Often she wears ear drops and pearls as ornaments. Her body is naturalistically rendered as a recumbent lioness. Such sphinxes were revived when the grottesche or "grotesque" decorations of the unearthed Domus Aurea of Nero were brought to light in late 15th-century Rome, and she was incorporated into the classical vocabulary of arabesque designs that spread throughout Europe in engravings during the 16th and 17th centuries. Sphinxes were included in the decoration of the loggia of the Vatican Palace by the workshop of Raphael (1515–20), which updated the vocabulary of the Roman grottesche.

The first appearances of sphinxes in French art are in the School of Fontainebleau in the 1520s and 1530s and she continues into the Late Baroque style of the French Régence (1715–1723). From France, she spread throughout Europe, becoming a regular feature of the outdoors decorative sculpture of 18th-century palace gardens, as in the Upper Belvedere Palace in Vienna, Sanssouci Park in Potsdam, La Granja in Spain, Branicki Palace in Białystok, or the late Rococo examples in the grounds of the Portuguese Queluz National Palace (of perhaps the 1760s), with ruffs and clothed chests ending with a little cape.

Sphinxes are a feature of the neoclassical interior decorations of Robert Adam and his followers, returning closer to the undressed style of the grottesche. They had an equal appeal to artists and designers of the Romanticism and subsequent Symbolism movements in the 19th century. Most of these sphinxes alluded to the Greek sphinx and the myth of Oedipus, rather than the Egyptian, although they may not have wings.

Greece

In the Bronze Age, the Hellenes had trade and cultural contacts with Egypt. Before the time that Alexander the Great occupied Egypt, the Greek name, sphinx, was already applied to these statues. [citation needed] The historians and geographers of Greece such as Herodotus wrote extensively about Egyptian culture.

There was a single sphinx in Greek mythology, a unique demon of destruction and bad luck. Apollodorus describes the sphinx as having a woman's face, the body and tail of a lion and the wings of a bird.[12] Pliny the Elder mentions that Ethiopia produces plenty of sphinxes, with brown hair and breasts,[13] corroborated by 20th-century archeologists.[14] Statius describes her as a winged monster, with pallid cheeks, eyes tainted with corruption, plumes clotted with gore and talons on livid hands.[15] Sometimes, the wings are specified to be those of an eagle, and the tail to be serpent-headed. [citation needed] According to Hesiod, the Sphinx was a daughter of Orthrus and an unknown she—either the Chimera, Echidna, or Ceto.[16] According to Apollodorus[12] and Lasus,[17] she was a daughter of Echidna and Typhon.

The sphinx was the emblem of the ancient city-state of Chios, and appeared on seals and the obverse side of coins from the 6th century BC until the 3rd century AD.[18]

Riddle of the Sphinx

The Sphinx is said to have guarded the entrance to the Greek city of Thebes, asking a riddle to travellers to allow them passage. The exact riddle asked by the Sphinx was not specified by early tellers of the myth, and was not standardized as the one given below until late in Greek history.[19]

It was said in late lore that Hera or Ares sent the Sphinx from her Aethiopian homeland (the Greeks always remembered the foreign origin of the Sphinx) to Thebes in Greece where she asked all passersby the most famous riddle in history: "Which creature has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?" She strangled and devoured anyone who could not answer. Oedipus solved the riddle by answering: "Man—who crawls on all fours as a baby, then walks on two feet as an adult, and then uses a walking stick in old age".[12] In some lesser accounts,[20] there was a second riddle: "There are two sisters: one gives birth to the other and she, in turn, gives birth to the first. Who are the two sisters?" The answer is "day and night" (both words—ἡμέρα and νύξ, respectively—are feminine in Ancient Greek). This second riddle is also found in a Gascon version of the myth and could be very ancient.[21]

Bested at last, the Sphinx then threw herself from her high rock and died;[22] or, in some versions Oedipus killed her.[23] An alternative version tells that she devoured herself.[citation needed] In both cases, Oedipus can therefore be recognized as a "liminal" or threshold figure, helping effect the transition between the old religious practices, represented by the death of the Sphinx, and the rise of the new, Olympian gods.[citation needed]

The riddle in popular culture

In Jean Cocteau's retelling of the Oedipus legend, The Infernal Machine, the Sphinx tells Oedipus the answer to the riddle in order to kill herself so that she did not have to kill any more, and also to make him love her. He leaves without ever thanking her for giving him the answer to the riddle. The scene ends when the Sphinx and Anubis ascend back to the heavens.

There are mythic, anthropological, psychoanalytic and parodic interpretations of the Riddle of the Sphinx, and of Oedipus's answer to it. Sigmund Freud describes "the question of where babies come from" as a riddle of the Sphinx.[24]

Numerous riddle books use the Sphinx in their title or illustrations.[25]

-

Funerary stele, 530 BC, Greece

-

Limestone funerary stele (shaft) surmounted by two sphinxes. Greece, 5th century BC.

-

Marble capital and finial in the form of a sphinx, 530 BC

-

Sphinxes on the Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon (430–420 BC)

Romania

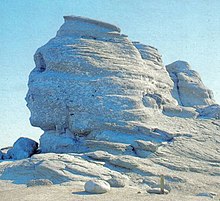

Sfinxul is a natural rock formation in the Bucegi Natural Park which is in the Bucegi Mountains of Romania. This rock formation is named for its resemblance to the Sphinx of Giza, and is located at an altitude of 2,216 metres (7,270 ft) within the Babele complex of rock formations.[26][27]

Asia

A composite mythological being with the body of a lion and the head of a human being is present in the traditions, mythology and art of South and Southeast Asia.[29] Variously known as puruṣamr̥ga (Sanskrit, "human-animal"), purushamirugam (Tamil, "human-animal"), naravirala (Sanskrit, "human-cat") in India, or as nara-simha (Sanskrit, "human-lion") in Sri Lanka, manussiha or manutthiha (Pali, "human-lion") in Myanmar, and norasingha (from Pali, "human-lion", a variation of the Sanskrit "nara-simha") or thep norasingha ("man-lion deity"), or nora nair in Thailand. Although, just like the "nara-simha", she/he has a head of a lion and the body of a human.

In contrast to the sphinxes in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Greece, of which the traditions largely have been lost due to the discontinuity of the civilization,[30] the traditions related to the "Asian sphinxes" are very much alive today. The earliest artistic depictions of "sphinxes" from the South Asian subcontinent are to some extent influenced by Hellenistic art and writings. These hail from the period when Buddhist art underwent a phase of Hellenistic influence. Numerous sphinxes can be seen on the gateways of Bharhut stupa, dating to the 1st century B.C.[28]

In South India, the "sphinx" is known as puruṣamr̥ga (Sanskrit) or purushamirugam (Tamil), meaning "human-animal". It is found depicted in sculptural art in temples and palaces where it serves an apotropaic purpose, just as the "sphinxes" in other parts of the ancient world.[31] It is said by the tradition, to take away the sins of the devotees when they enter a temple and to ward off evil in general. It is therefore often found in a strategic position on the gopuram or temple gateway, or near the entrance of the sanctum sanctorum.

The puruṣamr̥ga plays a significant role in daily as well as yearly ritual of South Indian Hindu temples. In the Shodhasha-Upakaara (or sixteen honors) ritual, performed between one and six times at significant sacred moments through the day, it decorates one of the lamps of the Deepaaradhana or lamp ceremony. And in several temples the puruṣamr̥ga is also one of the vahana or vehicles of the deity during the processions of the Brahmotsava or festival.

In Kanyakumari district, in the southernmost tip of the Indian subcontinent, during the night of Maha Shivaratri, devotees run 75 kilometres while visiting and worshiping at twelve Shiva temples. This Shiva Ottam or Running for Shiva is performed in commemoration of the story of the race between the Purushamirugam and Bhima, one of the Pandavas of the Hindu Epic Mahabharata.

The Indian conception of a sphinx that comes closest to the classic Greaco-Roman idea is the Sharabha and Gandabherunda, two mythical creatures, part lion, part human, part mammal and part bird, and the form of Sharabha that god Shiva took on and fought with the god Vishnu as Narasimha and Shiva as Sharabha was killed by Vishnu as Gandabherunda in the form of Narashima when Narashima killed Hiranyakashipu.

In Sri Lanka and India,[citation needed] the sphinx is known as narasimha or human-lion. As a sphinx, it has the body of a lion and the head of a human being, and is not to be confused with Narasimha, the fourth incarnation of the deity Vishnu; this avatara or incarnation of Vishnu has a human body and the head of a lion and Vishnu as Narashima killed Hiranyakashipu. The "sphinx" narasimha is part of the Buddhist tradition and functions as a guardian of the northern direction and also was depicted on banners.

In Burma (Myanmar), the sphinx-like statue, with a human head and two lion hindquarters, is known as Manussiha (manuthiha). It is depicted on the corners of Buddhist stupas, and its legends tell how it was created by Buddhist monks to protect a new-born royal baby from being devoured by ogresses.

Nora Nair, Norasingha and Thep Norasingha are three of the names under which the "sphinx" is known in Thailand. They are depicted as upright walking beings with the lower body of a lion or deer, and the upper body of a human. Often they are found as female-male pairs. Here, too, the sphinx serves a protective function. It also is enumerated among the mythological creatures that inhabit the ranges of the sacred mountain Himapan.[32]

Freemasonry

The sphinx imagery has historically been adopted into Masonic architecture and symbolism.[33]

Among the Egyptians, sphinxes were placed at the entrance of the temples to guard their mysteries, by warning those who penetrated within that they should conceal a knowledge of them from the uninitiated. Champollion said that the sphinx became successively the symbol of each of the gods. The placement of the sphinxes expressed the idea that all the gods were hidden from the people, and that the knowledge of them, guarded in the sanctuaries, was revealed to initiates only.

As a Masonic emblem, the sphinx has been adopted as a symbol of mystery, and as such often is found as a decoration sculptured in front of Masonic temples, or engraved at the head of Masonic documents.[34]

Similar hybrid creatures

With feline features

- Gopaitioshah – The Persian Gopat or Gopaitioshah is another creature that is similar to the Sphinx, being a winged bull or lion with human face.[35][36] The Gopat have been represented in ancient art of Iran since late second millennium BC, and was a common symbol for dominant royal power in ancient Iran. Gopats were common motifs in the art of Elamite period, Luristan, North and North West region of Iran in Iron Age, and Achaemenid art,[37] and can be found in texts such as the Bundahishn, the Dadestan-i Denig, the Menog-i Khrad, as well as in collections of tales, such as the Matikan-e yusht faryan and in its Islamic replication, the Marzubannama.[38]

- Löwenmensch figurine – The 32,000-year-old Aurignacian Löwenmensch figurine, also known as "lion-human" is the oldest known anthropomorphic statue, discovered in the Hohlenstein-Stadel, a German cave in 1939.[39]

- Manticore – The Manticore (Early Middle Persian: Mardyakhor or Martikhwar, means: Man-eater[40]) is a Persian legendary hybrid creature and another similar creature to the sphinx.

- Narasimha – Narasimha ("human-lion") is an incarnation (Avatara) of Vishnu in Hinduism in the Dashavatara of Vishnu who takes the form of half-man/half-Asiatic lion, having a human torso and lower body, but with a lion-like face and claws and in this avatara, Vishnu killed Hiranyakashipu as Narashima and saved the world from chaos in Hindu Mythology.

Without feline features

- In ancient Assyria, bas-reliefs of shedu bulls with the crowned bearded heads of kings guarded the entrances of temples.

- Many Greek mythological creatures who are archaic survivals of previous mythologies with respect to the classical Olympian mythology, like the centaurs, are similar to the Sphinx.

Gallery

-

Maned sphinx of Amenemhat III. 12th Dynasty, c. 1800 BC. State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich.

-

Egyptian sphinx from Hadrian's Villa at Tivoli. 1st century AD. State Museum of Egyptian Art, Munich.

-

Column base in the shape of a double sphinx. From Sam'al. 8th century BC. Museum of the Ancient Orient, Istanbul.

-

Hittite sphinx. Basalt. 8th century BC. From Sam'al. Museum of the Ancient Orient, Istanbul.

-

Achaemenid sphinx from Halicarnassus, capital of Caria, 355 BC. Found in Bodrum Castle, but possibly from the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

-

Head from a female sphinx, c. 1876–1842 BC, Brooklyn Museum

-

The Great Sphinx of Giza in 1858

-

Typical Egyptian sphinx with a human head (Museo Egizio, Turin)

-

Sphinx of Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut with unusual ear and ruff features, 1503–1482

-

3000-year-old sphinxes were imported from Egypt to embellish public spaces in Saint Petersburg and other European capitals.

-

Queluz wingless rococo sphinx

-

Classic Régence garden Sphinx in lead, Château Empain, the Parc d'Enghien, Belgium

-

Park Schönbusch in Aschaffenburg, Bavaria, 1789–90

-

Ingres, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1808, 1827

-

Oedipus and the Sphinx by Gustave Moreau, 1864

-

Sphinx at Plaza de los Emperadores (Parque de El Capricho, Madrid)

-

Marble sphinx on a cavetto capital, Attic, c. 580–575 BC

-

The Sphinx of Adi Gramaten, Eritrea

-

Wings of sphinxes from the Thinissut sanctuary, c. 1st century AD (Nabeul Museum, Tunisia)

-

An early Egyptian sphinx, Queen Hetepheres II from the Fourth Dynasty (Cairo Museum)

-

Picture of an Iranian Elamite Gopat on a seal, currently in the National Museum of Iran

-

An Iranian Luristan Bronze in the form of a Gopat, currently in the Cleveland Museum of Art

-

Picture of a Gopat on a golden rhyton from Amarlou, Iran, currently in the National Museum of Iran

-

Sculpture model of an Egyptian sphinx. Late Period, 664-332 BC. From Egypt. Neues Museum, Berlin.

See also

Similar hybrid creatures

- Lupul Dacic or the head of a wolf with the body of a snake, the sacred symbol of the Dacians, the ancient inhabitants of modern Romania.

- Anzû (older reading: Zû), Mesopotamian monster

- Chimera, Greek mythological hybrid monster

- Centaur and Ichthyocentaur, Greek horse and human hybrid, or horse, human, fish hybrid

- Cockatrice, snake with rooster's head and feet and bat's wings

- Dragon, European and East Asian reptile-like mythical creature

- Griffin or griffon, lion-bird hybrid

- Harpy, Greco-Roman mythological bird monster with woman's face

- Siren, Greco-Roman mythical creature with the combined features of a woman and bird, often a woman's head and breasts and a bird's body

- Lamassu, Assyrian deity, bull/lion-eagle-human hybrid

- Hippogryph, half eagle, half horse

- Manticore, Persian monster with a lion's body and a humanoid head.

- Nue, Japanese legendary creature

- Pegasus, winged stallion in Greek mythology

- Phoenix, self-regenerating bird in Greek mythology

- Pixiu or Pi Yao, Chinese mythical creature

- Qilin, Chinese/East Asian mythical hybrid creature

- Satyr, or Faun, a Greek or Roman mythical creature that is half human half goat

- Sharabha, Hindu mythology: lion-bird hybrid

- Simurgh, Iranian mythical flying creature

- Sirin, Russian mythological creature, half-woman half-bird

- Snow Lion, Tibetan mythological celestial animal

- Yali, Hindu mythological lion-elephant-horse hybrid

- Ziz, giant griffin-like bird in Jewish mythology

- Komainu to compare its use in Japanese culture

- Chinthe similar lion statues in Burma, Laos and Cambodia

- Shisa similar lion statues in the Ryukyu Islands

- Nian to compare with a similar but horned (unicorn) mythical beast

- Haetae to compare with similar lion-like statues in Korea.

Notes

- ^ "Dr. J's Lecture on Oedipus and the Sphinx". People.hsc.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ Kallich, Martin. "Oedipus and the Sphinx." Oedipus: Myth and Drama. N.p.: Western, 1968. N. pag. Print.

- ^ Stewart, Desmond. Pyramids and the Sphinx. [S.l.]: Newsweek, U.S., 72. Print.

- ^ Entry σφίγγω at LSJ. See Beekes, 2010: 1431-2.

- ^ Note that the γ takes on a 'ng' sound in front of both γ and ξ.

- ^ Bauer, S. Wise (2007). The History of the Ancient World. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 110–112. ISBN 978-0-393-05974-8.

- ^ Brian Dunning (2019). [1] Skeptoid Podcast, episode 693 'The Age of the Sphinx'

- ^ Strudwick, Helen (2006). The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 254–255. ISBN 978-1-4351-4654-9.

- ^ Regier, Willis Goth. Book of the Sphinx (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2004), 54, 59, 177.

- ^ Kuta, Sarah (8 March 2023). "Smiling Sphinx Statue Unearted in Egypt". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 3 April 2023.

- ^ Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium (2017). "Caresses". Google Arts and Culture.

- ^ a b c Apollodorus, Library Apollod. 3.5.8

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 8.30

- ^ p. 5,6,24. Fattovich, Rodolfo. "Remarks on the pre-Aksumite period in northern Ethiopia." Journal of Ethiopian Studies 23 (1990): 1-33.

- ^ Statius, Thebaid, 2.496

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 326–327. Who is meant as the mother is unclear, the problem arising from the ambiguous referent of the pronoun "she" in line 326 of the Theogony, see Clay, p.159, note 34; Most, p. 29 n. 20; Gantz, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Lasus fr. 3, on Lyra Graeca II

- ^ Sear, David (2010). Greek Imperial coins and their values – The Local Coinages of the Roman Empire. Nabu Press. p. xiv.

- ^ Edmunds, Lowell (1981). The Sphinx in the Oedipus Legend. Königstein im Taunus: Hain. ISBN 3-445-02184-8.

- ^ Grimal, Pierre (1996). The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. trans. A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-20102-5. (entry "Oedipus", p. 324)

- ^ Julien d'Huy (2012). L'Aquitaine sur la route d'Oedipe? La Sphinge comme motif préhistorique. Bulletin de la SERPE, 61: 15-21.

- ^ Apollod. 3.5.8

- ^ "Sphinx"Hornblower, Simon (2012). Oxford Classical Dictionary. Anthony Spawforth, Esther Eidinow. Oxford University Press.

- ^ 'An Autobiographical Study', Sigmund Freud, W. W. Norton & Company, 1963, p.39

- ^ Regier, Book of the Sphinx, chapter 4.

- ^ "Sfinxul din Muntii Bucegi". Travelworld.ro. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Louise McTigue, ed. (2014). "Bucegi Natural Park". Nature Flip. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

Latitude: 45.382416 Longitude: 25.449116. About Bucegi Natural Park: Located in south central Romania in the Bucegi Mountains, Bucegi Natural Park covers a total area of 325 km2 (~125 sq mi). Half falls within the Dâmbovita county with the remainder split relatively equally between Prahova and Brasov. Unsurprisingly, given its location, it is a mountainous landscape with caves, canyons, sinkholes, valleys and waterfalls, alongside meadows and forests. Significant features include the Babele (Old Women) and the Sphinx.

- ^ a b "Sphinxes of all sorts occur on the Bharhut gateways" Kosambi, Damodar Dharmanand (2002). Combined Methods in Indology and Other Writings. Oxford University Press. p. 459. ISBN 9780195642391.

- ^ Deekshitar, Raja. "Discovering the Anthropomorphic Lion in Indian Art." in Marg. A Magazine of the Arts. 55/4, 2004, p.34-41; Sphinx of India.

- ^ Demisch, Heinz (1977). Die Sphinx. Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart. Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Demisch, Heinz (1977). Die Sphinx. Geschichte ihrer Darstellung von den Anfangen bis zur Gegenwart. Stuttgart.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Thep Norasri". Himmapan.com. Retrieved 15 May 2014.

- ^ Freund, Charles Paul (5 November 1995). "From Satan to The Sphinx: The Masonic Mysteries of D.C.'s Map". The Washington Post. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Taylor, David A. "The Lost Symbol's Masonic Temple". Smithsonian. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ "Dadestan-i Denig, Question 90, Paragraph 4".

- ^ "Menog-i Khrad, Chapter 62".

- ^ Taheri, Sadreddin (2017). "The Semiotics of Archetypes, in the Art of Ancient Iran and its Adjacent Cultures". Tehran: Shour Afarin Publications. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Taheri, Sadreddin (2013). "Gopat and Shirdal in the Near East". نشریه هنرهای زیبا- هنرهای تجسمی. 17 (4(زمستان 1391)). Tehran: Honarhay-e Ziba Journal, Vol. 17, No. 4. doi:10.22059/jfava.2013.30063.

- ^ "New Life for the Lion Man – Archaeology Magazine Archive". archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- ^ Pausanias, Pausanias, Description of Greece, 9.21.4

References

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (1 June 1987). ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- Clay, Jenny Strauss, Hesiod's Cosmos, Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-521-82392-0.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Kallich, Martin. "Oedipus and the Sphinx." Oedipus: Myth and Drama. N.p.: Western, 1968. N. pag. Print.

- Most, G.W., Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia, Edited and translated by Glenn W. Most, Loeb Classical Library No. 57, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-674-99720-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Stewart, Desmond. Pyramids and the Sphinx. [S.l.]: Newsweek, U.S., 72. Print.

- Taheri, Sadreddin (2013). "Gopat (Sphinx) and Shirdal (Gryphon) in the Ancient Middle East". نشریه هنرهای زیبا- هنرهای تجسمی. 17 (4(زمستان 1391)). Tehran: Honarhay-e Ziba Journal, Vol. 17, No. 4. doi:10.22059/jfava.2013.30063.

Further reading

- Griffith, Francis Llewellyn; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). pp. 662–663.

- Dessenne, André. La Sphinx: Étude iconographique (in French). De Boccard, 1957.

External links

- Sphinxes

- Ancient Egyptian symbols

- Ancient Greek art

- Egyptian artefact types

- Egyptian legendary creatures

- Fantasy creatures

- Female legendary creatures

- Greek legendary creatures

- Human-headed mythical creatures

- Monsters in Greek mythology

- Mythological hybrids

- Mythological lions

- Mythological monsters

- Riddles

- Archaeology

![Classic Régence garden Sphinx in lead, Château Empain, the Parc d'Enghien [nl], Belgium](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/Enghien_CHSph1JPG.jpg/190px-Enghien_CHSph1JPG.jpg)