Banaba

Banaba (formerly Ocean Island) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 0°51′34″S 169°32′13″E / 0.85944°S 169.53694°E |

| Area | 6.29 km2 (2.43 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 81 m (266 ft) |

| Administration | |

Kiribati | |

| Island council | Banaba |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 330[1] (2020) |

| Pop. density | 52.5/km2 (136/sq mi) |

| Languages | Gilbertese |

| Ethnic groups | I-Kiribati (100%) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

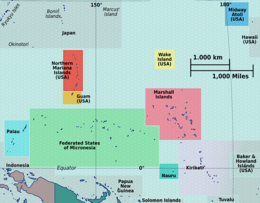

Banaba[notes 1] (/bəˈnɑːbə/; formerly Ocean Island) is an island of Kiribati in the Pacific Ocean. A solitary raised coral island west of the Gilbert Island Chain, it is the westernmost point of Kiribati, lying 185 miles (298 km) east of Nauru, which is also its nearest neighbour. It has an area of six square kilometres (2.3 sq mi),[2] and the highest point on the island is also the highest point in Kiribati, at 81 metres (266 ft) in height.[3] Along with Nauru and Makatea (French Polynesia), it is one of the important elevated phosphate-rich islands of the Pacific.[4]

History

According to Te Rii ni Banaba (The Backbone of Banaba) by Raobeia Ken Sigrah, Banaban oral history supports the claim that the people of the Te Aka clan, which originated in Melanesia, were the original inhabitants of Banaba, having arrived before the arrival of later migrations from the East Indies and Kiribati. The name Banaba in the local Gilbertese language is correctly spelled Bwanaba, but the Constitution of Kiribati (12 July 1979) writes Banaba, meaning "hollow land".

Sigrah makes also the controversial (and politically loaded) assertion that Banabans are ethnically distinct from other I-Kiribati.[5] The Banabans were assimilated only through forced migrations and the heavy impact of the discovery of phosphate in 1900. Prior to the relocation of its inhabitants at the end of World War II,[6] there were four villages on the island: Ooma (Uma), Tabiang, Tapiwa (Tabwewa) and Buakonikai. The local capital was Tabiang, now called Antereen.

| Village | Population (Census) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | |

| Antereen (Tabiang) | 16 | 108 | 83 | 102 | 115 |

| Umwa (Ooma, Uma) | 269 | 135 | 155 | 166 | 158 |

| Tabewa (Tapiwa, Tabwewa) | 54 | 58 | 57 | 57 | |

| Buakonikai | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 339 | 301 | 295 | 268 | 330 |

The first known sighting of Banaba by Europeans occurred on 3 January 1801. Captain Jared Gardner of the American vessel Diana sighted the island. Then in 1804, Captain John Mertho of the convict transport and merchant ship Ocean sighted the island and named it after his vessel.

Whaling vessels often visited the island in the nineteenth century for water and wood. The first recorded visit was by the Arabella in March 1832. The last known visit was by the Charles W. Morgan in January 1904.[7]

Banaba is prone to drought, as it is a high island with no natural streams and no water lens. The traditional source of water was a cave in which fresh water collected.[8] A three-year drought starting in 1873 killed more than three-quarters of the population and wiped out almost all of the trees; many of those who survived left the island on passing ships to escape the drought, and only some were able to return, often years later.[3]

Phosphate mining

The Pacific Islands Company, under John T. Arundel, identified that the petrified guano on Banaba consisted of high-grade phosphate rock. The agreement made with the Banabans was for the exclusive right to mine for 999 years for £50 a year. The terms of the licences were changed to provide for the payment of royalties and compensation for mining damage,[9][10] amounting to less than 0.1% of the profits the PIC made during its first 13 years.[11]

The Pacific Phosphate Company (PPC) built the Ocean Island Railway and mined phosphate from 1900 to 1919. In 1913, an anonymous correspondent to The New Age criticised the operation of the PPC under the title "Modern buccaneers in the West Pacific".[12] In 1919, the governments of the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand took over the operations of the Pacific Phosphate Company. The mining of the phosphate rock for fertiliser, which was carried out from 1900 to 1979, stripped away 90 per cent of the island's surface, the same process which occurred on Nauru from 1907 to the 1980s.[9] In June 1948, about 1,100 Gilbertese employed on Ocean Island refused to work; the key demand of the strikers was for higher wages of £10 a month to meet the increased price of goods sold in the trade store.[13]

After 1945, the British authorities relocated most of the population to Rabi Island, Fiji, with subsequent waves of emigration in 1977, and from 1981 to 1983. Some islanders subsequently returned, following the end of mining in 1979; approximately 300 were living on the island in 2001. The population of Banaba in the 2010 census was 295.[3] Globally, there are an estimated 6,000 individuals of Banaban descent.[14] On Rabi Island the names of settlements are the same authentic four names from Banaba Island.

Ocean Island Post Office opened on 1 January 1911 and was renamed Banaba around 1979.[15]

In the 1970s, the Banabans sued in the Court of England and Wales claiming that the UK Crown owed a fiduciary duty to the islanders when fixing the royalty payments and the difference in proper rates should be paid. In Tito v Waddell (No 2) [1977] Ch 106, Sir Robert Megarry V-C held that no fiduciary duties were owed, because the term "trust" in the Mining Ordinance 1927 was not used in the technical sense, but rather in the sense of an unenforceable government obligation.[16] The claim for the beach to be restored, from the 1948 agreement, was time-barred. The replanting obligations under the 1913 agreement were binding, but also they were limited to what was reasonably practicable.[16]

World War II and Japanese occupation

In July 1941, Australia and New Zealand troops evacuated British Phosphate Commission employees from Banaba (then known as Ocean Island). In February 1942, the Free French destroyer Le Triomphant evacuated the remaining Europeans and Chinese. Japanese forces occupied the island from 26 August 1942 until the end of World War II in 1945.[17] Cyril Cartwright, a member of the Gilbert and Ellice Colony administration, was subjected to ill-treatment and malnutrition.[18] He died on 23 April 1943.[18] Five Europeans also did not survive.[19]

On 20 August 1945, the Japanese troops murdered all but one of the remaining 200 Banabans on Ocean Island.[20] One man, Kabunare Koura, survived the massacre.[20][21] On 21 August, the surrender of the 500 Japanese soldiers was accepted by Resident Commissioner, Vivian Fox-Strangways and Brigadier J. R. Stevenson, who represented Lieutenant General Vernon Sturdee, the commander of the First Australian Army, on board the warship HMAS Diamantina.[19][22] Two Japanese officers were put on trial and convicted for the deaths.[20]

Several months later, Japan occupied Banaba, akin to the Gilbert group islands. While the Gilberts were reclaimed by the Allies in November 1943, the Japanese were ousted from Ocean Island only in 1945. During these three years, the majority of Banaba's inhabitants were either killed or deported to Nauru, the Caroline Islands, and the Marshall Islands. Nearly all of the 150 individuals left on Ocean Island at the Japanese surrender were killed by retreating forces before the island was reoccupied in September 1945. The island suffered extensive destruction, with houses and trees mostly obliterated.

Given these conditions, the British Government deemed it impractical to return the Banabans to their island and decided to temporarily resettle the 280 Banabans who survived the war on Nauru and Truk were resettled on Rabi Island in Fiji.[23] In December 1945, the Rabi Island Council was established, empowered to enact regulations, subject to the Governor of Fiji.

Post-1945 Decolonisation Period

Legal Challenges

In 1947, the British Phosphate Commissioners negotiated with the Banabans of Rabi Island for the acquisition of the remaining economically workable land on Ocean Island. The High Commissioner refrained from participating in the negotiations, leaving the Banabans without needed knowledge and advice. The Banabans agreed to sell their land for £82,000 and a fixed royalty rate, unaware that the British Phosphate Commissioners operated as a non-profit entity, aimed at allowing Australian and New Zealand farmers to gain advantages from acquiring phosphates at prices below the market rate.[24]

Sir Robert Megarry described the 1947 transaction as a "major disaster" for the Banabans. Despite later increases in royalty rates, resentment among the Banabans persisted, mostly due to the fact that royalties paid to the government of the Gilbert and Ellice Colony were higher than what they received. This general dissatisfaction along with the example of recently-independent island-nation Nauru led them demand independence for Ocean Island, however, these were not granted by the British, with concerns about revenue loss cited.

In 1968, the Banabans brought their case to the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonisation. Here, they garnered sympathy from committee members who urged the United Kingdom to take measures to improve the Banabans' situation, but refrained from supporting their plea for secession.

Simultaneously, the Banabans pursued legal action. In proceedings before the High Court in London, the Council of Leaders in Rabi Island, along with several Banaban landowners, alleged that the Crown held a fiduciary relationship with the Banabans. They claimed that in the 1931 and 1947 transactions, the Crown had breached this relationship due to a conflict of duty and interest.[25] The claim of fiduciary relationship was dismissed by the Court, because the term "trust" in the Mining Ordinance 1927 was not used in the technical sense, but rather in the sense of an unenforceable government obligation. The claim for the beach to be restored, from the 1948 agreement, was according to the Court, time barred.

Sir Megarry, however, who was highly reproachful of the British colonial administration, took the sides of the Banabans during the case, "Ocean Island no. 1," which claimed that the British Phosphate Commissioners did not not fulfil obligations under the 1913 agreement. The Commissioners were found liable for damages, but the plaintiffs were required to cover legal costs, which likely exceeded the awarded damages.

In 1977, a senior official, Mr. R.N. Posnett, was tasked with investigating financial and constitutional issues affecting the Banaban community's future. After visiting the Gilbert and Rabi Island, Posnett recommended a $A 10 million ex-gratia payment from the British, Australian, and New Zealand governments to the Banabans.[26]

Simultaneously, discussions about Banaba's constitutional status within the Gilbert Islands occurred in London in July 1977 between the British Government and a Gilbert Islands delegation. The delegation aimed to maintain the territorial integrity of the Gilbert Islands while seeking agreement with the Banaban community. Although talks in London and later in Tarawa in October 1977, known as the Bairiki Resolutions, appeared promising, including the proposal for a UN-supervised referendum on the separation of Banaba from the Gilberts, the resolutions were never implemented.[24]

Independence and Inclusion in the Republic of Kiribati

On July 12, 1979, the Gilbert Islands achieved complete independence from British colonial rule, marking the birth of the Republic of Kiribati. The term "Kiribati" is derived from the Gilbertese pronunciation of "Gilberts." In this newly formed nation, Banaba was integrated as one of its islands. The historical context of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands, characterised by Micronesian and Polynesian distinctions, posed challenges due to ethnic differences. The Ellice Islands adopted a "separation before self-government" strategy, leading to their constitutional independence in 1978 and the establishment of Tuvalu. Meanwhile, the Gilbert Islands, grappling with the intricate matter of Banaba islanders seeking secession, successfully navigated these complexities and emerged as the Republic of Kiribati in 1978, overcoming issues related to phosphate royalties and the resettlement of Banabans on Rabi Island in Fiji.[27]

Geography

The woodland of Banaba is now limited to the coastal area and is made up mostly of mangoes, flame trees, guavas, tapioca, and common Kiribati shrubs such as the saltbush. Having been mined for over 80 years, the centre of the island has no soil and is uninhabitable.[3]

The village Buakonikai (‘Te Aonoanne’) is now unoccupied. Banaba had three inhabited villages in the 2010 census; Tabwewa, Antereen (also called Tabiang) and Umwa.[3]

Climate

Banaba Island features a tropical rainforest climate, under Köppen's climate classification. Winds between north-east and south-east bring rainfall with large annual and seasonal variability. The period of lowest mean monthly rainfall starts in May and lasts until November. From December until April the monthly rainfall is on average higher than 120 mm.[28]

Demography

At the census of 1931, when the production of phosphate was at his highest point, and the headquarters of the entire colony concentrated there, the total population of Ocean Island was of 2,607 inhabitants (1,715 Gilbertese; 65 Elliceans; 129 Europeans; 698 “Mongoloids” [Asians]. After World War II, at the census of 1947, just after relocation of Banabans on Rabi Island in 1945, there were 2,060 left (considering notably the massacre of Banabans at the end of the Japanese occupation). The new ethnic distribution was then the following: 1,351 Gilbertese (the main losses); 441 Polynesians (the main gain from overcrowded Ellice Islands); 138 Europeans; 112 “Mongoloids”; 11 “half-caste” European-Gilbertese; 2 “half-caste” European-Ellicean; 4 “Gilbertese-Mongoloids” and 1 "other races".[29]

At the end of World War II, the Gilbert Islands' (and Fiji's) British colonial rulers decided to resettle most of Ocean Island's population on Rabi Island, because of the ongoing devastation of Banaba caused by phosphate mining. Some have since returned, but the majority have remained on Rabi or elsewhere in Fiji. The Banabans came to Fiji in three major waves, with the first group of 703, including 318 children, arriving on the BPC vessel, Triona, on 15 December 1945. Accompanying them were 300 other Gilbertese. The Banabans had been collected from Japanese internment camps on various islands, mainly Nauru and Kosrae; they were not given the option of returning to Banaba, on the grounds that the Japanese had destroyed their houses – this was not true. Only 100 to 200 returned and represent the landowners that stay in Fiji.

The population was 2,706 in 1963, 2,192 in 1968, 2,314 in 1973 and 2,201 in 1978, the year before the end of phosphate exploitation. At the following census, in 1985, only 46 Banabans were living. With the return of some people from Rabi Island, they were 284 in 1990, 339 in 1995, 276 in 2000, 301 in 2005, 295 in 2010 and 268 in 2015 (last available census). While only about 268 people live on Banaba, there is an estimated 6,000 people of Banaban descent in Fiji and other countries.[30][31]

Politics

Despite being part of Kiribati, its municipal administration is by the Rabi Council of Leaders and Elders, which is based on Rabi Island, in Fiji. Internationally, the Banaban community is often represented by the Banaban Community Presidium.[citation needed]

On 19 December 2005, Teitirake Corrie, the Rabi Island Council's representative to the Parliament of Kiribati, said that the Rabi Council was considering giving the right to remine Banaba Island to the government of Fiji. This followed the disappointment of the Rabi Islanders at the refusal of the Kiribati Parliament to grant a portion of the A$614 million trust fund from phosphate proceeds to elderly Rabi islanders. Corrie asserted that Banaba is the property of their descendants who live on Rabi, not of the Kiribati government, asserting that, "The trust fund also belongs to us even though we do not live in Kiribati". He condemned the Kiribati government's policy of not paying the islanders.

On 23 December, Reteta Rimon, Kiribati's High Commissioner to Fiji, clarified that Rabi Islanders were, in fact, entitled to Kiribati government benefits—but only if they returned to Kiribati. She called for negotiations between the Rabi Council of Leaders and the Kiribati government.

On 1 January 2006, Corrie called for Banaba to secede from Kiribati and join Fiji. Kiribati was using Banaban phosphate money for its own enrichment, he said; of the five thousand Banabans in Fiji, there were fewer than one hundred aged seventy or more who would be claiming pensions. [citation needed]

Future prospects

The stated wish of the Kiribati government to reopen mining on Banaba is strongly opposed by many in the Banaban diaspora.[citation needed]

Some of the leaders of the displaced Banaban community in Fiji have called for Banaba to be granted independence.[6] One reason given for the maintenance of a community on Banaba, at a monthly cost of F$12,000, is that if the island were to become uninhabited, the Kiribati government might take over the administration of the island, and integrate it with the rest of the country. Kiribati is believed to be anxious to retain Banaba, in the hope of mining it in the future. Like Kiritimati, it is a low-lying coral atoll but less susceptible to rising sea levels.

Notable people

Science fiction and fantasy author Hugh Cook lived on Ocean Island for two years as a child and it was an influence on much of his work. "When I was a small child – aged five and six, I think – I spent two years on Ocean Island, a dot in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. (Ocean Island is now called Banaba.) The Untunchilamon milieu has very much the flavor of Ocean Island – heat, flying fish, ghost crabs, red ants, scorpions, and the remnants of deceased military civilizations. (Ocean Island was littered with World War Two debris from the Japanese military occupation.)" [32]

Journalist Barbara Dreaver was born on Banaba and later moved to Tarawa and then New Zealand.[33]

See also

Notes

- ^ The correct spelling and etymology in Gilbertese should be Bwanaba but the Constitution of Kiribati writes Banaba. Because of the spelling in English or French, the name was very often written Paanapa or Paanopa, as it was in 1901 Act.

Further reading

- Correspondent. (5 June 1913). "Modern buccaneers in the West Pacific". The New Age, pp. 136–140 (Online). Available: [1] (accessed 12 June 2015).

- Treasure Islands: The Trials of the Ocean Islanders by Pearl Binder (published by Blond & Briggs in 1977), an emotional account of the Banaban's troubles.[34]

- Go Tell It to the Judge, a TV documentary by the BBC on the court case brought by the Banabans in London. It was first broadcast on 6 January 1977, shortly after judgement was reached.[35]

- An account of the Banaban's struggle with the British Phosphate Commission and the British government, as of 1985, can be found in the book On Fiji Islands by Canadian author Ronald Wright. This also contains descriptions of Rabi Island, to which the majority of Banabans were removed after World War II.[36]

- A Pattern of Islands, memoirs by Sir Arthur Grimble (published 1957), recounts his stay on the island at the beginning of his career, starting from 1914.

- Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba, Katerina Martina Teaiwa, 2015, Indiana University Press, pp 272.

- Maude, H. C.; Maude, H. E. (1932). "The Social Organization of Banaba or Ocean Island, Central Pacific". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 41 (4(164)): 262–301. JSTOR 20702446. OCLC 1250190393.

- Maude, H. C.; Maude, H. E., eds. (1994). The Book of Banaba: From the Maude and Grimble Papers; and Published Works. Institute of Pacific Studies of the University of the South Pacific. ISBN 978-0-646-20128-3.

- David Jehan: Tramways, Coconuts and Phosphate: A History of the Tramways of Ocean Island and Nauru. Light Railway Research Society of Australia Inc.

- Notes

- ^ "2020 Kiribati Population and Housing Census". Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Dahl, Arthur (12 July 1988). "Islands of Kiribati". Island Directory. UN System-Wide Earthwatch Web Site. Archived from the original on 11 February 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e "19. Banaba" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitenti – Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ C.Michael Hogan. 2011. Phosphate. Encyclopedia of Earth. Topic ed. Andy Jorgensen. Ed.-in-Chief C.J.Cleveland. National Council for Science and the Environment. Washington DC Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sigrah, Raobeia Ken, and Stacey M. King (2001). Te rii ni Banaba.. Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, Suva, Fiji. ISBN 982-02-0322-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Banaba: The island Australia ate". Radio National. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- ^ Langdon, Robert (1984) Where the whalers went: An index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, pp.198–201. ISBN 086784471X

- ^ "Nauru and Ocean Island". II(8) Pacific Islands Monthly. 15 March 1932. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ a b Maslyn Williams & Barrie Macdonald (1985). The Phosphateers. Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0-522-84302-6.

- ^ Ellis, Albert F. (1935). Ocean Island and Nauru; Their Story. Sydney, Australia: Angus and Robertson, limited. OCLC 3444055.

- ^ Gregory T. Cushman (2013). Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World. Cambridge University Press. p. 127.

- ^ Correspondent (5 June 1913). "Modern buccaneers in the West Pacific" (PDF). New Age: 136–140.

{{cite journal}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Gilbertese Strike on Ocean Island". XVIII(11) Pacific Islands Monthly. 18 March 1948. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Fiji Times, 27 December 2005[full citation needed]

- ^ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ a b [1977] Ch 106

- ^ Takizawa, Akira; Alsleben, Allan (1999–2000). "Japanese garrisons on the by-passed Pacific Islands 1944–1945". Forgotten Campaign: The Dutch East Indies Campaign 1941–1942.

- ^ a b "Wykehamist-War-Service-Record-and-Roll-of-Honour-1939-1945". militaryarchive.co.uk. 1945. p. 137. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Ocean Island Reoccupied". XVI(3) Pacific Islands Monthly. 16 October 1945. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b c "Japs Massacre Ocean Islanders After Surrender". XVI(10) Pacific Islands Monthly. 16 May 1946. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "Fate of Ocean Islanders – 100 Reported Murdered". XVI(4) Pacific Islands Monthly. 19 November 1945. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ "BANABA AND WORLD WAR 2". Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- ^ "New Home for Ocean Islanders". XVI(4) Pacific Islands Monthly. 19 November 1945. Retrieved 29 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Decolonization" (PDF). United Nations Department of Political Affairs, Trusteeship and Decolonization (15): 15. July 1979.

- ^ Conaglen, Matthew (2006). "A Re-Appraisal of the Fiduciary Self-Dealing and Fair-Dealing Rules". The Cambridge Law Journal. 65 (2): 366 – via JSTOR.

- ^ "Banabans". UK Parliament. 31 July 1978.

- ^ de Deckker, Paul (1996). "Decolonisation Processes in the South Pacific Islands: A Comparative Analysis Between Metropolitan Powers" (PDF). Victoria University of Wellington Law Research. 2: 8.

- ^ Burgess, S.M., The climate and weather of Western Kiribati, NZ Meteorological Service, Misc. Publ. 188(7), 1987, Wellington.

- ^ "Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony. A Report on the Results of the Census of the Population 1947". Endangered Archives Programme. British Library.

- ^ Teaiwa, Katerina Martina (2014). Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from Banaba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-01452-8.

- ^ Prestt, Kate (2017). "Australia's shameful chapter". 49(1) ANUReporter. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Hugh Cook Official Website". 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Bamber, Shaun (30 June 2021). "Tears, battles and making a difference - Barbara Dreaver's Pacific odyssey". Stuff. Retrieved 30 December 2023.

- ^ Wright, Ronald (1986). On Fiji Islands, New York:Penguin, p. 116.

- ^ Wright, Ronald (1986). On Fiji Islands, New York:Penguin, p. 152.

- ^ Wright, Ronald (1986). On Fiji Islands, New York:Penguin, pp. 115–154.

External links

- Banaban.com is a resource on Banaba, by Stacey King, covering history of Banabans and Banaba, as well as recent news

- Jane Resturehad an informative Banaba site Archived 21 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine