List of emperors of the Mughal Empire

| Shahenshah of Hindustan | |

|---|---|

Imperial | |

Mughal Imperial Seal | |

| Details | |

| Style | His Imperial Majesty |

| First monarch | Babur (as the successor to Sultan of Delhi) |

| Last monarch | Bahadur Shah II |

| Formation | 20 April 1526; 498 years ago |

| Abolition | 21 September 1857; 167 years ago |

| Residence | |

| Appointer | Hereditary |

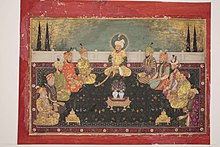

The Mughal emperors were the supreme monarchs of the Mughal Empire in the Indian subcontinent, mainly corresponding to the modern countries of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh. They ruled parts of India from 1526, and by 1707, ruled most of the subcontinent. Afterwards, they declined rapidly, but nominally ruled territories until the 1857 rebellion.

The Mughals were a branch of the Timurid dynasty of Turco-Mongol origin from Central Asia. Their founder Babur, a Timurid prince from the Fergana Valley (modern-day Uzbekistan), was a direct descendant of both Timur and Genghis Khan.

Many of the later Mughal emperors had significant Indian Rajput and Persian ancestry through marriage alliances as emperors were born to Rajput and Persian princesses.[1][2][3]

During the reign of Aurangzeb, the empire, as the world's largest economy and manufacturing power, worth over 25% of global GDP,[4] controlled nearly all of the Indian subcontinent, extending from Dhaka in the east to Kabul in the west and from Kashmir in the north to the Kaveri River in the south.[5]

Its population at the time has been estimated as between 110 and 150 million (a quarter of the world's population), over a territory of more than 4 million square kilometres (1.5 million square miles).[6] Mughal power rapidly dwindled during the 18th century and the last emperor, Bahadur Shah II, was deposed in 1857, with the establishment of the British Raj.[7]

Mughal Empire

The Mughal empire was founded by Babur, a Timurid prince and ruler from Central Asia. Babur was a direct descendant of Timur, the 14th century founder of the Timurid empire on his father's side, and Genghis Khan on his mother's side.[8] Ousted from his ancestral domains in Turkestan by Shaybani Khan, the 40-year-old prince Babur turned to India to satisfy his ambitions. He established himself in Kabul and then pushed steadily southward into India from Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass.[8] Babur's forces occupied much of northern India after his victory at Panipat in 1526.[8] The preoccupation with wars and military campaigns, however, did not allow the new emperor to consolidate the gains he had made in India.[9] The instability of the empire became evident under his son, Humayun, who was driven into exile in Persia by rebels.[8] Humayun's exile in Persia established diplomatic ties between the Safavid and Mughal courts and led to increasing West Asian cultural influence in the Mughal court. The restoration of Mughal rule began after Humayun's triumphant return from Persia in 1555, but he died from an accident shortly afterwards.[8] Humayun's son, Akbar, succeeded to the throne under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped consolidate the Mughal Empire in India.[10]

Through warfare and diplomacy, Akbar was able to extend the empire in all directions and controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent north of the Godavari river.[11] He created a new ruling elite loyal to him, implemented a modern administration, and encouraged cultural developments. He increased trade with European trading companies.[8] The Indian historian Abraham Eraly wrote that foreigners were often impressed by the fabulous wealth of the Mughal court, but the glittering court hid darker realities, namely that about a quarter of the empire's gross national product was owned by 655 families while the bulk of India's 120 million people lived in appalling poverty.[12] After suffering what appears to have been an epileptic seizure in 1578 while hunting tigers, which he regarded as a religious experience, Akbar grew disenchanted with Islam, and came to embrace a syncretistic mixture of Hinduism and Islam.[13] Akbar allowed freedom of religion at his court and attempted to resolve socio-political and cultural differences in his empire by establishing a new religion, Din-i-Ilahi, with strong characteristics of a ruling cult.[8] He left his son an internally stable state, which was in the midst of its golden age, but before long signs of political weakness would emerge.[8] Akbar was also interested in elevating the way individuals view leaders with the stylings of his clothes and ensemble.

Akbar's son, Jahangir, was addicted to opium, neglected the affairs of the state, and came under the influence of rival court cliques.[8] During the reign of Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan, the splendour of the Mughal court reached its peak, as exemplified by the Taj Mahal. The cost of maintaining the court, however, began to exceed the revenue being levied.[8]

Shah Jahan's eldest son, the liberal Dara Shikoh, became regent in 1658, as a result of his father's illness. Dara championed a syncretistic Hindu-Muslim religion and culture. With the support of the Islamic orthodoxy, however, a younger son of Shah Jahan, Aurangzeb, seized the throne. Aurangzeb defeated Dara in 1659 and had him executed.[8] Although Shah Jahan fully recovered from his illness, there was a succession war for the throne between Dara and Aurangzeb. Finally, Aurangzeb succeeded the throne and kept Shah Jahan under house arrest.

During Aurangzeb's reign, the empire gained political strength once more, and it became the world's largest economy, over a quarter of the world GDP,[citation needed] but his establishment of Sharia caused huge controversies. Aurangzeb expanded the empire to include a huge part of South Asia. At its peak, the kingdom stretched to 3.2 million square kilometres, including parts of what are now India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh.[14] After his death in 1707, "many parts of the empire were in open revolt."[8] Aurangzeb's attempts to reconquer his family's ancestral lands in Central Asia were not successful while his successful conquest of the Deccan region proved to be a pyrrhic victory that cost the empire heavily in both militarily and financially.[15] A further problem for Aurangzeb was the army had always been based upon the land-owning aristocracy of northern India who provided the cavalry for the campaigns, and the empire had nothing equivalent to the janissary corps of the Ottoman Empire.[15] The long and costly conquest of the Deccan had badly diminished the "aura of success" that surrounded Aurangzeb, and from the late 17th century onwards, the aristocracy became increasingly unwilling to provide forces for the empire's wars as the prospect of being rewarded with land as a result of a successful war was seen as less and less likely.[15]

Furthermore, at the conclusion of the conquest of the Deccan, Aurangzeb had very selectively rewarded some of the noble families with confiscated land in the Deccan, leaving aristocrats unrewarded with confiscated land feeling strongly disgruntled and unwilling to participate in further campaigns.[15] Aurangzeb's son, Shah Alam, repealed the religious policies of his father and attempted to reform the administration. "However, after his death in 1712, the Mughal dynasty sank into chaos and violent feuds. In the year 1719 alone, four emperors successively ascended the throne".[8]

During the reign of Muhammad Shah, the empire began to break up, and vast tracts of central India passed from Mughals to the Marathas hands. Mughal warfare had always been based upon heavy artillery for sieges, heavy cavalry for offensive operations and light cavalry for skirmishing and raids.[15] To control a region, the Mughals always sought to occupy a strategic fortress in some region, which would serve as a nodal point from which the Mughal army would emerge to take on any enemy that challenged the empire.[15] This system was not only expensive but also made the army somewhat inflexible as the assumption was always the enemy would retreat into a fortress to be besieged or would engage in a set-piece decisive battle of annihilation on open ground.[15] The Hindu Marathas were expert horsemen who refused to engage in set-piece battles, but rather engaged in campaigns of guerrilla warfare upon the Mughal supply lines.[15] The Marathas were unable to take the Mughal fortresses via a storm or formal siege as they lacked the artillery, but by constantly intercepting supply columns, they were able to starve Mughal fortresses into submission.[15]

Successive Mughal commanders refused to adjust their tactics and develop an appropriate counter-insurgency strategy, which led to the Mughals losing more and more ground to the Marathas.[15] The Indian campaign of Nader Shah of Persia culminated with the Sack of Delhi and shattered the remnants of Mughal power and prestige, as well as capturing the imperial treasury, thus drastically accelerating its decline. Many of the empire's elites now sought to control their own affairs and broke away to form independent kingdoms. The Mughal emperor, however, continued to be the highest manifestation of sovereignty. Not only the Muslim gentry, but the Maratha, Hindu, and Sikh leaders took part in ceremonial acknowledgements of the emperor as the sovereign of India.[16][17]

In the next decades, the Afghans, Sikhs, and Marathas battled against each other and the Mughals, revealing the fragmented state of the empire. The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II made futile attempts to reverse the empire's decline, but he ultimately had to seek the protection of outside powers. In 1784, the Marathas under Mahadaji Shinde won acknowledgement as the protectors of the emperor in Delhi, a state of affairs that continued until after the Second Anglo-Maratha War. Thereafter, the East India Company became the protectors of the Mughal dynasty in Delhi.[17] After 1835 the Company no longer recognised the authority of the emperor, accepting him only as 'King of Delhi' and removing all references to him from their coinage. After the Indian rebellion which he nominally led from 1857–58, the last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was deposed by the British, who then assumed formal control of a large part of the former empire,[8] marking the start of the British Raj.

Titular emperors

Over the course of the empire, there were several claimants to the Mughal throne who ascended the throne or claimed to do so but were never recognized.[18]

Here are the claimants to the Mughal throne historians recognise as titular Mughal emperors.

- Shahryar Mirza (1627 - 1628)

- Dawar Baksh (1627 - 1628)

- Jahangir II (1719 - 1720)

List of Mughal Emperors

| Portrait | Titular Name | Birth Name | Birth | Reign | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

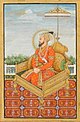

1

|

Babur بابر |

Zahir Ud-Din Muhammad Ghazi ظہیر الدین محمد |

14 February 1483 Andijan, Uzbekistan | 20 April 1526 – 26 December 1530 | 26 December 1530 (aged 47) Agra, India |

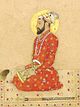

2

|

Humayun ہمایوں |

Nasir Ud-Din Baig Muhammad Khan ناصر الدین بیگ محمد خان |

6 March 1508 Kabul, Afghanistan | 26 December 1530 – 17 May 1540

22 February 1555 – 27 January 1556 |

27 January 1556 (aged 47) Delhi, India |

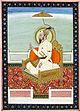

3

|

Akbar اکبر |

Abu'l Fath Jalal Ud-Din Muhammad ابوالفتح جلال الدین محمد |

15 October 1542 Umerkot, Pakistan | 11 February 1556 – 27 October 1605 | 27 October 1605 (aged 63) Agra, India |

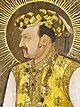

4

|

Jahangir جہانگیر |

Nur Ud-Din Baig Muhammad khan Salim نورالدین بیگ محمد خان سلیم |

31 August 1569 Agra, India | 3 November 1605 – 28 October 1627 | 28 October 1627 (aged 58) Jammu and Kashmir, India |

5

|

Shah Jahan شاہ جہان |

Shahab Ud-Din Muhammad Khurram شہاب الدین محمد خرم |

5 January 1592 Lahore, Pakistan | 19 January 1628 – 31 July 1658 | 22 January 1666 (aged 74) Agra, India |

6

|

Aurangzeb اورنگزیب Alamgir |

Muhi Ud-Din Muhammad محی الدین محمد |

3 November 1618 Gujarat, India | 31 July 1658 – 3 March 1707 | 3 March 1707 (aged 88) Ahmednagar, India |

7

|

Azam Shah اعظم شاہ |

Qutb Ud-Din Muhammad قطب الدين محمد |

28 June 1653 Burhanpur, India | 14 March 1707 – 20 June 1707 | 20 June 1707 (aged 53) Agra, India |

8

|

Bahadur Shah بہادر شاہ Shah Alam |

Abul-Nasr Sayyid Qutb-ud-din Mirza Muhammad Muazzam ابوالنصر سید قطب الدین مرزا محمد معظم |

14 October 1643 Burhanpur, India | 19 June 1707 – 27 February 1712 | 27 February 1712 (aged 68) Lahore, Pakistan |

9

|

Jahandar Shah جہاندار شاہ |

Mu'izz-ud-Din Beg Muhammad Khan Bahādur معیز الدین بیگ محمد خان بہادر |

9 May 1661 Deccan, India | 27 February 1712 – 11 February 1713 | 12 February 1713 (aged 51) Delhi, India |

10

|

Farrukhsiyar فرخ سیر |

Abu'l Muzaffar Muīn-ud-Dīn Muhammad Shāh Farrukhsiyar Alim Akbar Sāni Wālā Shān Pādshāh-i-bahr-u-bar ابوالمظفر معین الدین محمد شاہ فرخ سیار علیم اکبر ثانی والا شان پادشاہ البحر البر Puppet King Under the Sayyids of Barha |

20 August 1685 Aurangabad, India | 11 January 1713 – 28 February 1719 | 19 April 1719 (aged 33) Delhi, India |

11

|

Rafi ud-Darajat رفیع الدرجات |

Abu'l Barakat Shams-ud-Din Muhammad Rafi ud-Darajat Padshah Ghazi Shahanshah-i-Bahr-u-Bar ابوالبرکات شمس الدین محمد رفیع الدراجات پادشاہ غازی شہنشاہ البحر البر Puppet King Under the Sayyids of Barha |

1 December 1699 | 28 February 1719 – 6 June 1719 | 6 June 1719 (aged 19) Agra, India |

12

|

Shah Jahan II شاہ جہان دوم |

Rafi-ud-Din Muhammad Rafi-ud-Daulah رفیع الدین محمد رفیع الدولہ Puppet King Under the Sayyids of Barha |

5 January 1696 | 6 June 1719 – 17 September 1719 | 18 September 1719 (aged 23) Agra, India |

13

|

Muhammad Shah محمد شاہ |

Nasir-ud-Din Muḥammad Shah Roshan Akhtar Bahadur Ghazi ناصر الدین محمد شاہ روشن اختر بہادر غازی Puppet King Under the Sayyids of Barha |

7 August 1702 Ghazni, Afghanistan | 27 September 1719 – 26 April 1748 | 26 April 1748 (aged 45) Delhi, India |

14

|

Ahmad Shah Bahadur احمد شاہ بہادر |

Abu-Nasir Mujahid ud-din Muhammad Ahmad Shah Bahadur Ghazi ابو ناصر مجاہد الدین محمد احمد شاہ بہادر غازی |

23 December 1725 Delhi, India | 29 April 1748 – 2 June 1754 | 1 January 1775 (aged 49) Delhi, India |

15

|

Alamgir II عالمگیر دوم |

Aziz Ud-Din Muhammad عزیز اُلدین محمد |

6 June 1699 Burhanpur, India | 3 June 1754 – 29 November 1759 | 29 November 1759 (aged 60) Kotla Fateh Shah, India |

16

|

Shah Jahan III شاہ جہان سوم |

Muhi Ul-Millat محی اُلملت |

1711 | 10 December 1759 – 10 October 1760 | 1772 (aged 60–61) |

17

|

Shah Alam II شاہ عالم دوم |

Abdu'llah Jalal ud-din Abu'l Muzaffar Ham ud-din Muhammad 'Mirza Ali Gauhar عبدالله جلال الدین ابوالمظفر هم الدین محمد میرزا علی گوهر شاه علم دوم |

25 June 1728 Delhi, India | 10 October 1760 – 31 July 1788 | 19 November 1806 (aged 78) Delhi, India |

18

|

Shah Jahan IV جہان شاه چہارم |

Bidar Bakht Mahmud Shah Bahadur Jahan Shah بیدار بخت محمود شاه بهادر جہان شاہ |

1749 Delhi, India | 31 July 1788 – 11 October 1788 | 1790 (aged 40–41) Delhi, India |

19

|

Shah Alam II شاہ عالم دوم |

Abdu'llah Jalal ud-din Abu'l Muzaffar Ham ud-din Muhammad 'Mirza Ali Gauhar عبدالله جلال الدین ابوالمظفر هم الدین محمد میرزا علی گوهر شاه علم دوم Puppet King under the Maratha Empire |

25 June 1728 Delhi, India | 16 October 1788 – 19 November 1806 | 19 November 1806 (aged 78) Delhi, India |

20

|

Akbar Shah II اکبر شاہ دوم |

Sultan Ibn Sultan Sahib al-Mufazi Wali Ni'mat Haqiqi Khudavand Mujazi Abu Nasir Mu'in al-Din Muhammad Akbar Shah Pad-Shah Ghazi سلطان ابن سلطان صاحب المفاضی ولی نعمت حقی خداوند مجازی ابو ناصر معین الدین محمد اکبر شاہ پاد شاہ غازی Puppet King under the East India Company |

22 April 1760 Mukundpur, India | 19 November 1806 – 28 September 1837 | 28 September 1837 (aged 77) Delhi, India |

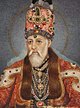

21

|

Bahadur Shah II Zafar بہادر شاہ ظفر |

Abu Zafar Siraj Ud-Din Muhammad ابو ظفر سراج اُلدین محمد |

24 October 1775 Delhi, India | 28 September 1837 – 21 September 1857 | 7 November 1862 (aged 87) Rangoon, Myanmar |

Note: The Baburid emperors practiced polygamy. Besides their wives, they also had several concubines in their harem, who produced children. This makes it difficult to identify all the offspring of each emperor.[19]

Family tree of Mughal emperors

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Jeroen Duindam (2015), Dynasties: A Global History of Power, 1300–1800, page 105 Archived 6 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine, Cambridge University Press

- ^ Mohammada, Malika (1 January 2007). The Foundations of the Composite Culture in India. Akkar Books. p. 300. ISBN 978-8-189-83318-3.

- ^ Dirk Collier (2016). The Great Mughals and their India. Hay House. p. 15. ISBN 9789384544980.

- ^ "The World Economy (GDP) : Historical Statistics by Professor Angus Maddison" Archived 5 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine . World Economy. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ^ Chandra, Satish. Medieval India: From Sultanate to the Mughals. p. 202.

- ^ Richards, John F. (1 January 2016). Johnson, Gordon; Bayly, C. A. (eds.). The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge history of India: 1.5. Vol. I. The Mughals and their Contemporaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 190. ISBN 978-0521251198.

- ^ Spear 1990, pp. 147–148

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic Visual History of the World. National Geographic Society. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0-7922-3695-5.

- ^ Keay, 293–296

- ^ Keay, 309–311

- ^ Keay, 311–319

- ^ Eraly, Abraham The Mughal Throne:The Saga of India's Great Emperors, London: Phonenix, 2004 p. 520.

- ^ Eraly, Abraham The Mughal Throne The Sage of India's Great Emperors, London: Phonenix, 2004 p. 191.

- ^ "The great Aurangzeb is everybody's least favourite Mughal – Audrey Truschke | Aeon Essays". Aeon. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j D'souza, Rohan "Crisis before the Fall: Some Speculations on the Decline of the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals" pp. 3–30 from Social Scientist, Volume 30, Issue # 9/10, September–October 2002 p. 21.

- ^ Keay, 361–363, 385–386

- ^ a b Bose, Sugata; Jalal, Ayesha (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-203-71253-5.

- ^ "The Mughal emperors in India", The Caliphate, Routledge, pp. 161–164, 18 November 2016, doi:10.4324/9781315443249-20, ISBN 978-1-315-44324-9, retrieved 7 January 2023

- ^ Dalrymple, William (2006). The Last Mughal The Fall Of A Dynasty. London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-4088-0092-8.

Sources

- Keay, John, India, a History, 2000, HarperCollins, ISBN 0002557177

- Spear, Percival (1990) [First published 1965], A History of India, Volume 2, New Delhi and London: Penguin Books. Pp. 298, ISBN 978-0-14-013836-8.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – India Archived 14 July 2012 at archive.today Pakistan Archived 29 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Country Studies. Federal Research Division. – India Archived 14 July 2012 at archive.today Pakistan Archived 29 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra; Pusalker, A. D.; Majumdar, A. K., eds. (1973). The History and Culture of the Indian People. Vol. VII: The Mughal Empire. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.