The Watermelon Woman

| The Watermelon Woman | |

|---|---|

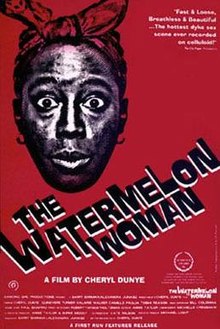

Promotional release poster | |

| Directed by | Cheryl Dunye |

| Written by | Cheryl Dunye |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Michelle Crenshaw |

| Edited by | Cheryl Dunye[1] |

| Music by | Paul Shapiro |

| Distributed by | First Run Features |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000[2] |

The Watermelon Woman is a 1996 American romantic comedy-drama film written, directed, and edited by Cheryl Dunye. The first feature film directed by a black lesbian,[3][4] it stars Dunye as Cheryl, a young black lesbian working a day job in a video store while trying to make a film about Fae Richards, a black actress from the 1930s known for playing the stereotypical "mammy" roles relegated to black actresses during the period.

The Watermelon Woman was produced on a budget of $300,000, financed by a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), as well as a fundraiser, and donations from friends of Dunye. The film was partly inspired by and dedicated to the memory of such Black actresses as Louise Beavers, Hattie McDaniel, and Butterfly McQueen.[5][6] Fae Richards is a fictional character created by Dunye for the film as both an amalgamation of and stand-in for Black actresses sidelined or forgotten in film history, and as a result of the film's budget being unable to afford archive footage of real-life actresses.[6]

The Watermelon Woman premiered at the 1996 Berlin International Film Festival. The film received generally positive reviews and is considered a landmark in New Queer Cinema.[7] It garnered controversy for a lesbian sex scene that prompted a writer for The Washington Times to question its NEA funding, which in turn led to the NEA restructuring their grant system. In 2021, The Watermelon Woman was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[8]

Plot

Cheryl is a 25-year-old African-American lesbian who works at a video rental store in Philadelphia with her friend Tamara. She is interested in films from the 1930s and 1940s that feature Black actresses, noting that the actresses in these roles are often not credited. After watching a film titled Plantation Memories in which a Black actress playing a mammy is credited only as "The Watermelon Woman", she decides to make a documentary in which she attempts to uncover the Watermelon Woman's identity and her own.

Cheryl begins interviewing subjects for her documentary: her mother, who recalls seeing the Watermelon Woman singing in clubs in Philadelphia; Lee Edwards, a local expert on African-American cinema; and her mother's friend Shirley, who is a lesbian and "in the family." Shirley tells Cheryl that the Watermelon Woman's name was Fae Richards, that Fae was a lesbian, and that she used to sing in clubs "for all us stone butches". She suggests that Fae was in a relationship with Martha Page, the white director of Plantation Memories. Cheryl later begins dating Diana, a white lesbian at the video rental store.

After interviewing cultural critic Camille Paglia, Cheryl visits the Center for Lesbian Information and Technology ("CLIT"), where she finds an autographed photo of Fae Richards signed for her "special friend" June Walker. Diana later helps Cheryl contact Martha Page's sister, who denies that Martha was a lesbian. Tamara tells Cheryl that she disapproves of her relationship with Diana; she accuses Cheryl of wanting to be white, and Diana of having a fetish for Black women.

Upon contacting June Walker, Cheryl learns that Fae is deceased and that June is a Black woman who was Fae's partner of 20 years. They arrange to meet, though June is hospitalized prior to their meeting and leaves a letter for Cheryl. In the letter, June expresses anger over the frequent rumors that Fae and Martha were a couple, and urges Cheryl to tell the true story of their relationship and Fae Richards' life. Having separated from Diana and fallen out with Tamara, Cheryl finishes her documentary, never managing to make further contact with June.

Cast

- Cheryl Dunye as Cheryl

- Guinevere Turner as Diana

- Valarie Walker as Tamara

- Lisa Marie Bronson as Fae "The Watermelon Woman" Richards

- Cheryl Clarke as June Walker

- Irene Dunye as herself

- Brian Freeman as Lee Edwards

- Ira Jeffries as Shirley Hamilton

- Alexandra Juhasz as Martha Page

- Camille Paglia as herself

- Sarah Schulman as CLIT archivist

- V.S. Brodie as Karaoke Singer

- Shelley Olivier as Annie Heath

- David Rakoff as Librarian

- Toshi Reagon as Street Musician

- Christopher Ridenhour as Bob

- Kathy Robertson as Yvette

- Jocelyn Taylor as Stacey

- Robert Reid-Pharr as Fred de Shields[9]

Production

In 1993 Dunye was doing research for a class on Black film history, by looking for information on Black actresses in early films. Many times the credits for these women were left out of the film. Dunye decided that she was going to use her work to create a story for Black women in early films, which became The Watermelon Woman. When confronted about the omissions in film history, Dunye replied, "That it's going to take more than just my film for that picture to be corrected," says Dunye. "There needs to be more work, there needs to be more Black protagonists. There are a lot of talented actresses that have nothing to do but "mammy" roles again and again, modern day mammies. There needs to be a focus that gets them working, getting some of those Academy Awards like they should."[10] The film's title is a play on the Melvin Van Peebles's film Watermelon Man (1970).[11]

The Watermelon Woman was made on a budget of $300,000, financed by a $31,500 grant from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), a fundraiser, and donations from friends of Dunye.[2][12][13] The photographic Fae Richards Archive, documenting the fictional actress' life, was created by New York City-based photographer Zoe Leonard.[14] Made up of 78 images, the collection later was exhibited in galleries and as a book. Some of the photos were auctioned off as a fundraiser to fund the film's production.[7]

For the production of the film, Dunye conducted her research at the Lesbian Herstory Archives and the Library of Congress. However, she quickly discovered that neither had the specific resources she was looking for and accessing them was beyond her budget for the film, causing her to stage 78 of the archival photographs featured in the film.[15][7] The production team decided against going to the Library of Congress to obtain materials and license them due to the costs, so instead Dunye and Zoe Leonard created new footage meant to resemble video from the 1930s and had playwright Ira Jeffries take additional photographs in the same style.[16]

In the film, the protagonist Cheryl, played by the director, is an aspiring Black lesbian filmmaker attempting to bring about the history of Black lesbians in cinematic history while attempting to produce her own work, saying "our stories have never been told."[17] The mockumentary explores the difficulty in navigating archival sources that either excludes or ignores Black lesbians working in Hollywood,[15] particularly that of actress Fae Richards whose character bore the name that provides the title for the film.[11] The film also features a number of appearances by homosexual art figures such as Cheryl Clarke, Camille Paglia, David Rakoff, Sarah Schulman and others.[17]

Dunye has said she found inspiration from the films Swoon (1992) and Norman... Is That You? (1976).[7]

Release

The Watermelon Woman premiered at the 1996 Berlin International Film Festival and played at several other international film festivals during 1996 and 1997, including the New York Lesbian & Gay Film Festival, L.A. Outfest, the San Francisco International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival, the Tokyo International Lesbian & Gay Film Festival, the Créteil International Women's Film Festival, the London Lesbian and Gay Film Festival, and the Toronto International Film Festival.[18][19]

The Watermelon Woman aired on the Sundance Channel on August 12, 1998. Dunye was the only female director to be showcased during that month. Dunye was selected as one of POWER UP's 2008 Top-10 Powerful Women in Showbiz.[20]

The film was released theatrically in the United States on March 5, 1997, distributed by First Run Features.[18]

In 2016, to celebrate the film's 20th anniversary, the Metrograph in New York City screened the film for one week.[7]

Reception and legacy

Critical response

Critical reviews of the film were generally positive. Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film "both stimulating and funny".[21] He praised Dunye for her "talent and open-heartedness" and enjoyed the film's moments of comedy.[21] He said that the film "lets you find your own way to its central message about cultural history and the invisibility of those shunted to the margins."[21] Writing for the San Francisco Chronicle, Ruthie Stein had a similar opinion to Holden, writing that, despite the seriousness of the film's topics, it "never takes itself too seriously."[22] She praised Dunye's "engaging personality" and said that she "has infused [the film] with a lightness that seems to match her spirit."[22] The Advocate's Anne Stockwell wrote that "this rollicking, sexy movie never gets self-important."[14] She praised the "footage" of Fae Richards and Zoe Leonard's work on the photo archive of the fictional actress as "one of the film's joys".[14]

Emanuel Levy rated the film as a "B", writing that it was "only a matter of time before a woman of color made a lesbian film."[23] He said that while "[p]oking fun at various sacred cows in American culture", it "makes statements about the power of narrative and the ownership of history."[23] In a review for The Austin Chronicle, Marjorie Baumgarten called the film "smart, sexy [...] funny, historically aware, and stunningly contemporary."[24] Kevin Thomas, writing for the Los Angeles Times, called the film a "wry and exhilarating comedy, at once romantic and sharply observant."[25]

To celebrate the 30th anniversary of the Teddy Awards, the film was selected to be shown at the 66th Berlin International Film Festival in February 2016.[26]

In 2016, a print of The Watermelon Woman was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) as part of its film collection.[27][28] On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a score of 92% from 63 reviews, with an average rating of 7.2/10. The site's consensus states, "An auspicious debut for writer-director Cheryl Dunye, The Watermelon Woman tells a fresh story in wittily irreverent style."[29] On Metacritic, the film holds a weighted average score of 74 out of 100 based on 11 reviews, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[30]

Accolades

In 1996, The Watermelon Woman won the Teddy Award for Best Feature Film at the Berlin International Film Festival,[31] and the Audience Award for Outstanding Narrative Feature at L.A. Outfest.[32]

The significance of the film was recognized with the 2021 Cinema Eye Honors Legacy Award.[33]

Criticism of NEA funding

On March 3, 1996, Jeannine DeLombard reviewed The Watermelon Woman for Philadelphia City Paper, describing the sex scene between Cheryl and Diana as "the hottest dyke sex scene ever recorded on celluloid".[34] On June 14, Julia Duin wrote an article for The Washington Times, quoting DeLombard's review and questioning the $31,500 grant given to Dunye by the NEA.[13][35]

Representative Peter Hoekstra, the chairman of the House Education and Workforce Committee's United States House Education Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, also read DeLombard's review. Hoekstra wrote a letter to the NEA chairwoman, Jane Alexander, stating that The Watermelon Woman "is one of several gay- and lesbian-themed works cited by the Michigan Republican as evidence of 'the serious possibility that taxpayer money is being used to fund the production and distribution of patently offensive and possibly pornographic movies.'" A spokesperson for Hoekstra said that he had no problem with gay content, just those that contained explicit sex.[36] Because of this controversy, the NEA restructured itself by awarding grants to specific projects rather than giving funding straight to arts groups for disbursement.[36]

Home media

The Watermelon Woman was released on DVD on September 5, 2000, and again on 2018.[29][37]

The film was restored in 2K and released on Blu-ray by The Criterion Collection on July 11, 2023.[38][39][40]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman (1996): Crew". AllMovie. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Haslett, T.; N. Abiaka (April 12, 1997). "Cheryl Dunye — Interview". Black Cultural Studies Web Site Collective. Archived from the original on January 22, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ Sullivan, Laura L. (2000). "Chasing Fae: "The Watermelon Woman" and Black Lesbian Possibility" (PDF). Callaloo. 23 (1): 448–460. doi:10.1353/cal.2000.0070. S2CID 161364954. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Keough, Peter (May 8, 1997), "Slice of life — The Watermelon Woman refreshes", The Phoenix, archived from the original on December 5, 1998, retrieved April 29, 2008

- ^ Rich, Frank (March 13, 1997), "Lesbian Lookout", The New York Times, retrieved April 29, 2008

- ^ a b Oloukoï, Chrystel (February 27, 2021). "The Watermelon Woman at 25: the Black lesbian classic that wears its brilliance lightly". BFI.org.uk. British Film Institute. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Kelsey, Colleen (November 11, 2016). "Cheryl Dunye's Alternative Histories". Interview Magazine. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

- ^ Tartaglione, Nancy (December 14, 2021). "National Film Registry Adds Return Of The Jedi, Fellowship Of The Ring, Strangers On A Train, Sounder, WALL-E & More". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 14, 2021.

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman — Cast", Movies & TV Dept., The New York Times, 2009, archived from the original on June 4, 2009, retrieved June 6, 2008

- ^ Trudi, Perkins (June 1997), "Caution: She'll Make You Think!", Lesbian News, 22 (11)

- ^ a b Richardson, Matt (2011). "Our Stories Have Never Been Told: Preliminary Thoughts on Black Lesbian Cultural Production as Historiography in The Watermelon Woman". Black Camera. 2 (2): 100–113. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.2.2.100. JSTOR 10.2979/blackcamera.2.2.100. S2CID 144355769.

- ^ McHugh, p.275.

- ^ a b Warner, David (October 17, 1996), "Dunye, Denzel and more", Philadelphia City Paper, archived from the original on January 14, 2002, retrieved April 28, 2008

- ^ a b c Stockwell, Anne (March 4, 1997), "Color-corrected film", The Advocate, LPI Media, p. 53, retrieved May 15, 2010

- ^ a b Bryan-Wilson, Julia, and Cheryl Dunye. "Imaginary Archives: A Dialogue." Art Journal, vol. 72, no. 2, 2013, pp. 82–89., JSTOR 43188602.

- ^ Anderson, Tre'vell (2016-11-27). "Director Cheryl Dunye on her groundbreaking LGBTQ film 'The Watermelon Woman,' 20 years later". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b Michel, Frann (Summer 2007). "Eating the (M)Other: Cheryl Dunye's Feature Films and Black Matrilineage". Rhizomes: Cultural Studies in Emerging Knowledge. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ a b "The Watermelon Woman", Variety, archived from the original on May 5, 2008, retrieved April 27, 2008

- ^ "Official Site". 2005. Archived from the original on July 8, 2011. Retrieved April 27, 2008.

- ^ "Cheryl Dunye - California College of the Arts". www.cca.edu. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ a b c Holden, Stephen (March 5, 1997), "On Black Films and Breezy Lesbians", The New York Times, retrieved May 13, 2010

- ^ a b Stein, Ruthe (July 25, 1997), "'Watermelon Woman' Digs Fruitfully Into a Faux Past", San Francisco Chronicle, Hearst Corporation, retrieved May 13, 2010

- ^ a b Levy, Emanuel (April 14, 2009). "Watermelon Woman, The (1996): Cheryl Dunye's Significant Lesbian Film (LGBTQ)". EmanuelLevy.com. Retrieved May 13, 2010.

- ^ Baumgarten, Marjorie (July 18, 1997), "Film Listings: The Watermelon Woman", The Austin Chronicle, Austin Chronicle Corp., retrieved May 13, 2010

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (28 March 1997). ""Wry 'Woman' Explores Race, Sexuality"". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Berlinale 2016: Panorama Celebrates Teddy Award's 30th Anniversary and Announces First Titles in Programme". Berlinale. Archived from the original on 21 December 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman. 1996. Directed by Cheryl Dunye". MoMA.

- ^ "AFI Movie Club: The Watermelon Woman". AFI.com. American Film Institute. October 19, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Watermelon Woman". Rotten Tomatoes. 5 March 1996. Retrieved April 28, 2008.

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman Reviews". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved June 14, 2023.

- ^ Walber, Daniel (6 February 2014). "The Out Take: 10 Fantastic Teddy Award-Winning LGBT Films To Watch Right Now". MTV.com. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Swartz, Shauna (2006-03-15). "Review of The Watermelon Woman". AfterEllen.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2007. Retrieved 2008-04-27.

- ^ Jeffrey, Andrew (October 20, 2021). ""City So Real" and "American Utopia" highlight 15th Cinema Eye Honors nominations". realscreen.com. Retrieved 2021-11-01.

- ^ DeLombard, Jeannine (March 3, 1996), "The Watermelon Woman Review", Philadelphia City Paper, archived from the original on September 25, 2022, retrieved September 25, 2022

- ^ Wallace, p.457.

- ^ a b Moss, J. Jennings (April 1, 1997), "The NEA gets gay-bashed — National Endowment for the Arts", The Advocate, LPI Media, p. 55, retrieved May 13, 2010

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman (Restored 20th Anniversary Edition)". Amazon.com.

- ^ "The Watermelon Woman (1996)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ Humphrey, Julia (April 14, 2023). "'After Hours', 'The Watermelon Woman', and More Coming to Criterion in July". Collider. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ Kois, Dan (July 11, 2023). "The Radical Classic That's Finally Coming to the Criterion Collection". Slate Magazine. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

Bibliography

- McHugh, Kathleen (2002), "Autobiography", in Lewis, Jon (ed.), The End of Cinema as We Know It, Pluto Press, ISBN 0-7453-1879-7

- Sullivan, Laura L. (2004), "Chasing Fae: The Watermelon Woman and Black Lesbian Possibility", in Bobo, Jacqueline; Hudley, Cynthia; Michel, Claudine (eds.), The Black Studies Reader, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-94553-4, JSTOR 3299571

- Wallace, Michele (2004), Dark Designs and Visual Culture, Duke University Press, pp. 457–459, ISBN 0-8223-3413-5

- Richardson, Matt (Spring 2011). "Our Stories Have Never Been Told: Preliminary Thoughts on Black Lesbian Cultural Production as Historiography in The Watermelon Woman". Black Camera. 2 (2 Special Issue: Beyond Normative: Sexuality and Eroticism in Black Film, Cinema, and Video). Indiana University Press: 100–113. doi:10.2979/blackcamera.2.2.100. JSTOR 10.2979. S2CID 144355769.

Further reading

- Thomas, Kevin (1997-03-28). "Wry 'Woman' Explores Race, Sexuality". Los Angeles Times.

External links

- 1996 films

- 1996 drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- Lesbian-related films

- African-American LGBT-related films

- African-American films

- American independent films

- 1996 independent films

- Films set in Philadelphia

- American LGBT-related films

- LGBT-related drama films

- 1996 LGBT-related films

- Films about film directors and producers

- Films about filmmaking

- Films about race and ethnicity

- Lesbian working-class culture

- Lesbian feminist mass media

- 1996 directorial debut films

- 1990s feminist films

- United States National Film Registry films

- LGBT-related controversies in film

- Sexual-related controversies in film

- National Endowment for the Arts

- 1990s American films