Lucretius

Titus Lucretius Carus | |

|---|---|

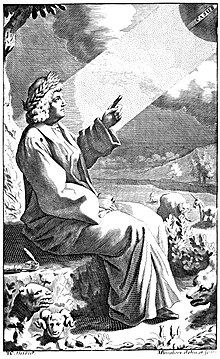

Modern bust of Lucretius | |

| Born | c. 99 BC |

| Died | c. 55 BC (aged around 44) |

| Era | Hellenistic philosophy |

| School | Epicureanism Atomism Materialism |

Main interests | Ethics, metaphysics, atomic theory[1] |

Titus Lucretius Carus (/ˈtaɪtəs luːˈkriːʃəs/ TY-təs loo-KREE-shəs, Latin: [ˈtitus luˈkreːti.us ˈkaːrus]; c. 99 – c. 55 BC) was a Roman poet and philosopher. His only known work is the philosophical poem De rerum natura, a didactic work about the tenets and philosophy of Epicureanism, which usually is translated into English as On the Nature of Things—and somewhat less often as On the Nature of the Universe. Very little is known about Lucretius's life; the only certainty is that he was either a friend or client of Gaius Memmius, to whom the poem was addressed and dedicated.[2] De rerum natura was a considerable influence on the Augustan poets, particularly Virgil (in his Aeneid and Georgics, and to a lesser extent on the Eclogues) and Horace.[3] The work was almost lost during the Middle Ages, but was rediscovered in 1417 in a monastery in Germany[4] by Poggio Bracciolini and it played an important role both in the development of atomism (Lucretius was an important influence on Pierre Gassendi)[5] and the efforts of various figures of the Enlightenment era to construct a new Christian humanism.

Life

And now, good Memmius, receptive ears

And keen intelligence detached from cares

I pray you bring to true philosophy

If I must speak, my noble Memmius,

As nature's majesty now known demands

Virtually nothing is known about the life of Lucretius, and there is insufficient basis for a confident assertion of the dates of Lucretius's birth or death in other sources. Another, yet briefer, note is found in the Chronicon of Donatus's pupil, Jerome. Writing four centuries after Lucretius's death, he enters under the 171st Olympiad: "Titus Lucretius the poet is born."[6] If Jerome is accurate about Lucretius's age (43) when Lucretius died (discussed below), then it may be concluded he was born in 99 or 98 BC.[7][8] Less specific estimates place the birth of Lucretius in the 90s BC and his death in the 50s BC,[9][10] in agreement with the poem's many allusions to the tumultuous state of political affairs in Rome and its civil strife.

Lucretius probably was a member of the aristocratic gens Lucretia, and his work shows an intimate knowledge of the luxurious lifestyle in Rome.[11] Lucretius's love of the countryside invites speculation that he inhabited family-owned rural estates, as did many wealthy Roman families, and he certainly was expensively educated with a mastery of Latin, Greek, literature, and philosophy.[11]

A brief biographical note is found in Aelius Donatus's Life of Virgil, which seems to be derived from an earlier work by Suetonius.[12] The note reads: "The first years of his life Virgil spent in Cremona until the assumption of his toga virilis on his 17th birthday (when the same two men held the consulate as when he was born), and it so happened that on the very same day Lucretius the poet passed away." However, although Lucretius certainly lived and died around the time that Virgil and Cicero flourished, the information in this particular testimony is internally inconsistent: if Virgil was born in 70 BC, his 17th birthday would be in 53. The two consuls of 70 BC, Pompey and Crassus, stood together as consuls again in 55, not 53.

Another note regarding Lucretius's biography is found in Jerome's Chronicon, where he contends that Lucretius "was driven mad by a love potion, and when, during the intervals of his insanity, he had written a number of books, which were later emended by Cicero, he killed himself by his own hand in the 44th year of his life."[6] The claim that he was driven mad by a love potion, although defended by such scholars as Reale and Catan,[13] is often dismissed as the result of historical confusion,[2] or anti-Epicurean bias.[14] In some accounts the administration of the toxic aphrodisiac is attributed to his wife Lucilia. Regardless, Jerome's image of Lucretius as a lovesick, mad poet continued to have significant influence on modern scholarship until quite recently, although it now is accepted that such a report is inaccurate.[15]

De rerum natura

His poem De rerum natura (usually translated as "On the Nature of Things" or "On the Nature of the Universe") transmits the ideas of Epicureanism, which includes atomism and cosmology. Lucretius was the first writer known to introduce Roman readers to Epicurean philosophy.[16] The poem, written in some 7,400 dactylic hexameters, is divided into six untitled books, and explores Epicurean physics through richly poetic language and metaphors. Lucretius presents the principles of atomism, the nature of the mind and soul, explanations of sensation and thought, the development of the world and its phenomena, and explains a variety of celestial and terrestrial phenomena. The universe described in the poem operates according to these physical principles, guided by fortuna, "chance", and not the divine intervention of the traditional Roman deities[17] and the religious explanations of the natural world.

Within this work, Lucretius makes reference to the cultural and technological development of humans in his use of available materials, tools, and weapons through prehistory to Lucretius's own time. He specifies the earliest weapons as hands, nails, and teeth. These were followed by stones, branches, and, once humans could kindle and control it, fire. He then refers to "tough iron" and copper in that order, but goes on to say that copper was the primary means of tilling the soil and the basis of weaponry until, "by slow degrees", the iron sword became predominant (it still was in his day) and "the bronze sickle fell into disrepute" as iron ploughs were introduced.[1] He had earlier envisaged a pre-technological, pre-literary kind of human whose life was lived "in the fashion of wild beasts roaming at large".[18] From this beginning, he theorised, there followed the development in turn of crude huts, use and kindling of fire, clothing, language, family, and city-states. He believed that smelting of metal, and perhaps too, the firing of pottery, was discovered by accident: for example, the result of a forest fire. He does specify, however, that the use of copper followed the use of stones and branches and preceded the use of iron.[18]

Lucretius seems to equate copper with bronze, an alloy of copper and tin that has much greater resilience than copper; both copper and bronze were superseded by iron during his millennium (1000 BC to 1 BC). He may have considered bronze to be a stronger variety of copper and not necessarily a wholly individual material. Lucretius is believed to be the first to put forward a theory of the successive uses of first wood and stone, then copper and bronze, and finally iron. Although his theory lay dormant for many centuries, it was revived in the nineteenth century and he has been credited with originating the concept of the three-age system that was formalised from 1834 by C. J. Thomsen.[19]

-

De rerum natura (1570)

-

1754 copy of De rerum natura

-

Frontispiece of a 1754 copy of De rerum natura

-

1683 English translation of De rerum natura

-

Title page of a 1683 English translation of De rerum natura

Reception

In a letter by Cicero to his brother Quintus in February 54 BC, Cicero said: "The poems of Lucretius are as you write: they exhibit many flashes of genius, and yet show great mastership."[20] In the work of another author in late Republican Rome, Virgil writes in the second book of his Georgics, apparently referring to Lucretius,[21] "Happy is he who has discovered the causes of things and has cast beneath his feet[a] all fears, unavoidable fate, and the din of the devouring Underworld."[22]

Natural philosophy

An early thinker in what grew to become the study of evolution, Lucretius believed nature experiments endlessly across the aeons, and the organisms that adapt best to their environment have the best chance of surviving. Living organisms survived because of the commensurate relationship between their strength, speed, or intellect and the external dynamics of their environment. Prior to Charles Darwin's 1859 publication of On the Origin of Species, the natural philosophy of Lucretius typified one of the foremost non-teleological and mechanistic accounts of the creation and evolution of life.[23] In contrast to modern thought on the subject, he did not believe that new species evolved from previously existing ones. Lucretius challenged the assumption that humans are necessarily superior to animals, noting that mammalian mothers in the wild recognize and nurture their offspring as do human mothers.[24]

Despite his advocacy of empiricism and his many correct conjectures about atomism and the nature of the physical world, Lucretius concludes his first book stressing the absurdity of the (by then well-established) spherical Earth theory, although he never explicitly said that he held the flat Earth view.[25]

While Epicurus left open the possibility for free will by arguing for the uncertainty of the paths of atoms, Lucretius viewed the soul or mind as emerging from fortuitous arrangements of distinct particles.[26]

See also

- The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, a modern historiography by Stephen Greenblatt

- List of English translations of De rerum natura

- Javelin argument

Notes

- ^ subiecit pedibus; cf. Lucretius 1.78: religio pedibus subiecta, "religion lies cast beneath our feet"

References

- ^ a b Lucretius. De rerum natura, Book V, around Line 1200 ff.

- ^ a b Melville & Fowler (2008), p. xii.

- ^ Reckford, K. J. Some studies in Horace's odes on love

- ^ Greenblatt (2009), p. 44.

- ^ Fisher, Saul (2009). "Pierre Gassendi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ a b Jerome, Chronicon.

- ^ Bailey (1947), pp. 1–3.

- ^ Smith (1992), pp. x–xi.

- ^ Kenney (1971), p. 6.

- ^ Costa (1984), p. ix.

- ^ a b Melville & Fowler (2008), Foreword.

- ^ Horsfall (2000), p. 3.

- ^ Reale & Catan (1980), p. 414.

- ^ Smith (2011), p. vii.

- ^ Gale (2007), p. 2.

- ^ Gale (2007), p. 35.

- ^ In particular, De rerum natura 5.107 (fortuna gubernans, "guiding chance" or "fortune at the helm"): see Monica R. Gale, Myth and Poetry in Lucretius (Cambridge University Press, 1994, 1996 reprint), pp. 213, 223–224 online and Lucretius (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 238 online.

- ^ a b Lucretius. De rerum natura, Book V, around line 940 ff.

- ^ Barnes, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Cicero, 2.9.

- ^ Smith (1975), intro.

- ^ Virgil, 2.490.

- ^ Campbell, Gordon (2003). Lucretius on Creation and Evolution: A Commentary on De rerum natura 5.772-1104. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–6. ISBN 0199263965.

- ^ Massaro, Alma (2014-11-11). "The Living in Lucretius' De rerum natura. Animals' ataraxia and Humans' Distress". Relations. Beyond Anthropocentrism. 2 (2): 45–58. doi:10.7358/rela-2014-002-mass. ISSN 2280-9643.

- ^ Hannam, James (29 April 2019). "Atoms and flat-earth ethics". Aeon. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

- ^ Gillispie, Charles Coulston (1960). The Edge of Objectivity: An Essay in the History of Scientific Ideas. Princeton University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-691-02350-6.

Bibliography

- Bailey, C. (1947). "Prolegomena". Lucretius's De rerum natura.

- Barnes, Harry Elmer (1937). An Intellectual and Cultural History of the Western World, Volume One. Dover Publications. OCLC 390382.

- Cicero. "Letters to his brother Quintus". Translated by Evelyn Shuckburgh. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Costa, C. D. N. (1984). "Introduction". Lucretius: De Rerum Natura V. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814457-1.

- Dalzell, A. (1982). "Lucretius". The Cambridge History of Classical Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gale, M.R. (2007). Oxford Readings in Classical Studies: Lucretius. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926034-8.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2009). The Swerve: How the World Became Modern. New York: WW. Norton and Company.

- Horsfall, N. (2000). A Companion to the Study of Virgil. ISBN 978-90-04-11951-2. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Kenney, E. J. (1971). "Introduction". Lucretius: De rerum natura. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29177-4.

- Melville, Ronald; Fowler, Don and Peta, eds. (2008) [1999]. Lucretius: On the Nature of the Universe. Oxford World's Classics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-162327-1.

- Reale, G.; Catan, J. (1980). A History of Ancient Philosophy: The Systems of the Hellenistic Age. SUNY Press.

- Santayana, George (1910). "Three philosophical poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe". Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Smith, M. (1992). "Introduction". De rerum natura. Loeb Classical Library.

- Smith, M. F. (1975). De rerum natura. Loeb Classical Library.

- Smith, M. F. (2011) [2001]. Lucretius, On the Nature of Things. Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-587-1. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- Stearns, J. B. (December 1931). "Lucretius and Memmius". The Classical Weekly. 25 (9): 67–68. doi:10.2307/4389660. JSTOR 4389660.

- Virgil. "Georgics". Retrieved 16 May 2012.

External links

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Works by Lucretius at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Lucretius at the Internet Archive

- Works by Lucretius at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Lucretius at Perseus Project

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry by David Simpson

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Lucretius's works: text, concordances and frequency list

- Bibliography De rerum natura Book III (archived 26 November 2006)

- Online Galleries, History of Science Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries High-resolution images of works by Lucretius in .jpg and .tiff format.

- Lucretius: De rerum natura (1475–1494), digitised codex at Somni

- Titi Lucretii Cari De rerum natura libri sex, published in Paris 1563, later owned and annotated by Montaigne, fully digitised in Cambridge Digital Library

- Discussion Forum For Lucretius and Epicurean Philosophy

- Is nature continuous or discrete? How the atomist error was born