Obeah

Obeah, or Obayi, is a series of African diasporic spell-casting and healing traditions found in the former British colonies of the Caribbean. These traditions derive much from traditional West African practices that have undergone cultural creolization. There is much regional variation in the practice of Obeah, which is followed by practitioners called Obeahmen and Obeahwomen.

Obeahmen and Obeahwomen serve a range of clients in assisting them with their problems. A central role is played by healing practices, often incorporating herbal and animal ingredients. It often also involves measures designed to achieve justice for the client. These practices often make reference to supernatural forces, resulting in Obeah sometimes being characterised as a religious practice. Obeah is said to be difficult to define, as it is believed by some to not be a single, unified set of practices, since the word "Obeah" was historically not often used to describe one's own practices.[1]

Obeah developed among African diasporic communities in various British Caribbean colonies following the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries. It formed through the adaptation of the traditional religious practices that enslaved West Africans, especially from the Ashanti and other Tshi-speaking peoples, brought to these colonies. There, they also absorbed European influences, especially from Christianity, the religion of the British colonial elites. These elites disapproved of African traditional religions and introduced various laws to curtail and prohibit them. This suppression meant that Obeah emerged as a system of practical rituals and procedures rather than as a broader religious system involving deity worship and communal rites. In this way, Obeah differs from more worship-focused African diasporic religions in the Caribbean, such as Haitian Vodou, Cuban Santería and Palo, or Jamaican Obeah. Since the 1980s, Obeah's practitioners have campaigned to remove legal restrictions against their practices in various Caribbean countries.

Variants of Obeah are practiced in the Caribbean nations of the Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname, Turks and Caicos Islands, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Virgin Islands.[2] The practice can also be found outside the Caribbean, in countries like the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom.

Definitions and terminology

The Hispanic studies scholars Margarite Fernández Olmos and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert defined Obeah as "a set of hybrid or creolized beliefs dependent on ritual invocation, fetishes, and charms".[3] Obeah incorporates both spell-casting and healing practices, largely of African origin.[3] These often rely on a knowledge of the properties of various animal and herbal ingredients.[3] Fernández Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert took the view that Obeah was not a religion per se, but is a term applied to "any African-derived practice with religious elements".[3]

It is found primarily in the former British colonies of the Caribbean.[3] Obeah revolves around one-to-one consultations between practitioners and their clients.[4] The term "Obeah" encompasses a varied range of traditions that display regional variation.[5] It is highly heterogenous.[5]

Obeah bears similarities with Quimbois, a related practice in the French Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique.[6] Fernández Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert suggested that Quimbois was essentially "a variation of Obeah".[7] Obeah differs from African diasporic religions from elsewhere in the Caribbean, such as Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santeria, in historically lacking a liturgy and communal rituals.[5]

Many practitioners of Obeah do not see their adherence to be at odds with Christianity.[8] In Trinidad, various Obeah practitioners are also involved in the Orisha religion.[9] Given certain similarities between Obeah and the Cuban religion of Palo, it is possible that Obeah practices were introduced to adherents of the latter system amid Jamaican migration to Cuba from 1925 onward.[10] In parts of the West Indies, South Asian migration has resulted in syncretisms between Obeah and Hinduism.[11] In Guyana, one Obeahman also served as a Hindu priest.[11]

Terms for practitioners

Obeah is practiced by both males and females, typically referred to as Obeahmen and Obeahwomen respectively. "Obi" or "Obayifo" can often be used as a title. [4] In the Bahamas, commonly used terms for a practitioner is Bush man or bush doctor;[4] and in Trinidad a common term is Wanga man.[4] In Grenada they are sometimes called Scientists,[4] and in Guyana as Professor, Madame, Pundit, Maraj, and work-man.[4] Practitioners of Quimbois are referred to as quimboiseurs, sorciers, and gadé zaffés.[7]

Beliefs and practices

Common goals in Obeah include attracting a partner, finding lost objects, resolving legal issues, getting someone out of prison, attracting luck for gambling or games, and wreaking revenge.[11]

Spirits

Central to Obeah is the relationship between humans and spirits.[12] Unlike other Afro-Caribbean religious traditions, such as Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería, Obeah does not strictly centre around deities who manifest through divination and the possession of their worshippers. However, practitioners can choose to work with Deities in their practice as they do with spirits.[5]

These spirits and deities can be "called" or summoned to assist the Obeah practitioner, but are not worshipped.[12]

Obeahmen and Obeahwomen

In Obeah tradition, it is typically believed that practitioners will be born with special powers; they are sometimes referred to as having been "born with the gift".[4] It is taught that possession of these powers may be revealed to the individual through dreams or visions in late childhood or early adolescence.[13] In Caribbean lore, it is sometimes believed that an Obeah practitioner will bear a physical disability, such as a blind eye, a club foot, or a deformed hand, and that their powers are a compensation for this.[8]

Traditionally, it is often believed that being an Obeah practitioner passes hereditarily, from a parent to their eldest child.[14] Alternatively, it is believed someone may become a practitioner following a traumatic event in their life.[14] Once they have decided to pursue the practice, a person typically becomes the apprentice of an established Obeahman or woman.[14] According to folk tradition, this apprenticeship should take place in the forest and last for a year, a notion that derives from older African ideas.[14] In practice, apprenticeships can last up to five or six years.[14]

A practitioner's success with attracting clients is usually rooted in their reputation.[15] Older Obeahmen/women are usually regarded more highly than younger ones.[8] They do not normally wear special clothing to mark out their identity.[8] In Trinidad and Tobago, 21st-century Obeah practitioners often advertise their services in the classified advert columns of newspapers.[4]

Clients will typically pay for the services of an Obeah practitioner, the size of the fee often being connected to the client's means.[15]

Healing and Herbalism

The main social function of an Obeah practitioner is often as a herbalist.[16] To assist with healing a client's ailments, the Obeahman/woman will often utilise baths, massages, and mixtures of various ingredients.[16] "Bush baths" are often applied to relieve fevers, and involve a range of different herbal ingredients placed within hot water.[16]

"Knowing the poisons" has historically been useful within the practice in the Caribbean. Enslaved practitioners knew how to identify poisons to poison slave masters and seek freedom.

In Obeah traditions, plants are believed to absorb cosmic properties from the sun, moon, and planets.[17]

Divination

In Guyana, South Asians have added chiromancy or palm reading to the styles of divination employed by Obeah practitioners.[18]

Practitioners also use geomancy, "throwing the lots" and cowrie shell throwing to divine.

History

Obeah practices largely derive from Ashanti origins.[3] The Ashanti and other Tshi-speaking peoples from the Gold Coast formed the largest group of enslaved people in the British Caribbean colonies.[3] Obeah was first identified in the British colonies of the Caribbean during the 17th century.[19]

In parts of the Caribbean where Obeah developed, enslaved people were taken from a variety of African nations with differing spiritual practices and religions. It is from these arrivals and their spiritualisms that the Caribbean form of Obeah originates. The origins of the word "Obeah" have been contested in the academic community for nearly a century; there is not a widely accepted consensus on what region or language the word derives from, and there are politics behind every hypothesis. Orlando Patterson promoted an Akan-Twi etymology, suggesting that the word came from communities in the Gold Coast.[20]

In British colonial communities, aside from referring to the set of spiritual practices, “Obeah” also came to refer to a physical object, such as a talisman or charm, that was used for evil magical purposes. The item was referred to as an Obeah-item (e.g. an 'obeah ring' or an 'obeah-stick', translated as: ring used for witchcraft or stick used for witchcraft respectively).[21] Obeah incorporated various beliefs from the religions of later migrants to the colonies where it was present. Obeah also influenced other religions in the Caribbean, e.g. Christianity, which incorporated some Obeah beliefs.[2][22][23]

Akan origin hypothesis

Patterson and other proponents of the Akan-Twi hypothesis argued that the word was derived from obayifo, a word associated with malevolent magic by Ashanti priests which means a person who possesses "witch power".[24] [25][26] Kwasi Konadu suggested a somewhat updated version of this etymology, suggesting that bayi, the neutral force used by the obayifo, is the source material – a word with a slightly less negative connotation.[27]

The first time in Jamaican history the term "obeah" was used in the colonial literature was in reference to Nanny of the Maroons, an Akan woman, considered the ancestor of the Windward Maroon community and celebrated for her role in winning the First Maroon War and securing a land treaty in 1740. Nanny was described as an old 'witch' and a 'Hagg' by English soldier Philip Thicknesse in his memoirs.[28][29][30] Obeah has also received a great deal of attention for its role in Tacky's Rebellion (also an Akan), the 1760 conflict that spurred the passage of the first Jamaican anti-Obeah law.[31] The term "Myal" was first recorded by Edward Long in 1774 when describing a ritual dance done by Jamaican enslaved Africans. At first the practices of Obeah and Myal were not considered different by law. However, over time those who focused on Myal within church worships have become known as Revivalists. They are involved in spirit affairs, and involved themselves with Jamaican Native Baptist churches, bringing Myal rituals into the churches. Over time these Myal influenced churches (otherwise called the Jamaican revivalist church or Pocomania ) began preaching the importance of baptisms and the eradication of Obeah, thus formally separating the two traditions.[32]

Igbo origin hypothesis

Despite its associations with a number of Akan slaves and rebellions, that explanation for the origin of Obeah has been criticised by several writers who hold that an Igbo origin is more likely.[33] According to W. E. B. Du Bois Institute database,[34] he traces Obeah to the Dibia or Obia (Template:Lang-ig)[35] traditions of the Igbo people.[36][37] Specialists in Obia (also spelled Obea) were known as Ndi Obia (Template:Lang-ig) and practised the same activities as the Obeah men and women of the Caribbean like predicting the future and manufacturing charms.[38][39] Among the Igbo there were oracles known as Obiạ which were said to be able to talk.[40] Parts of the Caribbean where Obeah was most active imported a large number of its slaves from the Igbo-dominated Bight of Biafra.[34] This interpretation is also favored by Kenneth Bilby, arguing that “dibia’ connotes a neutral “master of knowledge and wisdom.”[41]

Efik origin hypothesis

In another hypothesis, the Efik language is the root of Obeah where the word obeah comes from the Efik ubio meaning 'a bad omen'.[42] Melville Herskovits endorsed a different Efik origin, arguing that obeah was a corruption of an Efik word for “doctor” or the corruption of the Bahumono word for "native doctor".[41]

Beginnings

The earliest known mention of Obeah comes from Barbados in 1710 from letters written by Thomas Walduck. He writes in part, that an Obia Negro can torment another by sending uncountable pains in different parts of their Body, lameness, madness, loss of speech, lose the use of all their limbs without any pain.[44]

The term 'Obeah' is first found in documents from the early 18th century, as in its connection to Nanny of the Maroons. Colonial sources referred to the spiritual powers attributed to her in a number of derogatory ways, ranging from referring to her as “the rebel’s old obeah woman”[45] to characterizing her as “unsexed” and more bloodthirsty than Maroon men.[46] Maroon oral traditions discuss her feats of science in rich detail. She is said to have used her obeah powers to kill British soldiers in Nanny's Pot, a boiling pot without a flame below it that soldiers would lean into and fall in,[47] to quickly grow food for her starving forces,[48] and to catch British bullets and either fire them back or attack the soldiers with a machete.[49]

The Jamaican Assembly passed a number of draconian laws to regulate the slaves in the aftermath of Tacky's War, including the banning of obeah.[50][51] During the rebellion, Tacky is said to have consulted an Obeahman who prepared for his forces a substance that would make them immune to bullets, which boosted their confidence in executing the rebellion.[52][53]

In 1787, a letter written to The Times referred to "Obiu-women" interpreting the wishes of the dead at the funeral of a murdered slave in Jamaica: a footnote explained the term as meaning "Wise-women".[54] The practice of obeah with regards to healing led to the Jamaican 18th and 19th century traditions of "doctresses", such as Grace Donne (who nursed her lover, Simon Taylor (sugar planter)), Sarah Adams, Cubah Cornwallis, Mary Seacole, and Mrs Grant (who was the mother of Mary Seacole). These doctresses practised the use of hygiene and the applications of herbs decades before they were adopted by European doctors and nurses.[55][56]

The British colonial authorities saw Obeah as a threat to the stability on their plantations and criminalised it.[19] The British colonial elites often feared that obeahmen would incite rebellions against British rule.[19] This colonial suppression eradicated the African-derived communal rituals that involved song, dance, and offerings to spirits.[5] In the British Caribbean, communal rituals oriented towards deities only persevered in pockets, as with Obeah in Jamaica and Orisha in Trinidad.[57]

Discrimination

Written accounts of Obeah in the 19th and 20th century were largely produced by white visitors to the Caribbean who saw the tradition and its practitioners as being sinister.[58]

A continuing source of anxiety related to Obeah was the belief that practitioners were skilled in using poisons, as mentioned in Matthew Lewis's Journal of a West India Proprietor. Many Jamaicans accused women of such poisonings; one case Lewis discussed was that of a young woman named Minetta who was brought to trial for attempting to poison her master.[59] Lewis and others often characterized the women they accused of poisonings as being manipulated by Obeahmen, who they contended actually provided the women with the materials for poisonings.[60] The laws forbidding Obeah reflected this fear: an anti-Obeah law passed in Barbados in 1818 specifically forbade the possession of "any poison, or any noxious or destructive substance".[61] A doctor who examined the medicine chest of an Obeah man arrested in Jamaica in 1866 identified white arsenic as one of the powders in it, but could not identify the others. The unnamed correspondent reporting this affirmed "The Jamaica herbal is an extensive one, and comprises some highly poisonous juices, of which the Obeah men have a perfect knowledge."[62]

During the conflict between Revivalist and Obeah, the Obeah man positioned themselves as the "good" opponents to "evil" Obeah.[63] They claimed that Obeah men stole people's shadows, and they set themselves up as the helpers of those who wished to have their shadows restored. Revivalists contacted spirits in order to expose the evil works they ascribed to the Obeah men, and led public parades which resulted in crowd-hysteria that engendered violent antagonism against Obeah men. The public "discovery" of buried Obeah charms, presumed to be of evil intent, led on more than one occasion to violence against the rival Obeah practitioners. Such conflicts between supposedly “good” and “evil” spiritual work could sometimes be found within plantation communities. In one 1821 case brought before court in Berbice, an enslaved woman named Madalon allegedly died as a result of being accused of malevolent obeah that caused the drivers at Op Hoop Van Beter plantation to fall ill.[64] The man implicated in her death, a spiritual worker named Willem, conducted an illegal Minje Mama dance to divine the source of the Obeah, and after she was chosen as the suspect, she was tortured to death.[65]

Laws were passed that limited both Obeah and Revivalist traditions.[66]

Modern history

The late 20th century saw growing migration from the West Indies to metropolitan urban centres like Miami, New York, Toronto, and London, where practitioners of Obeah interacted with followers of other Afro-Caribbean traditions like Santeria, Vodou, and Espiritismus.[19] Some communities of Obeah practitioners are trying to develop communal rituals.[5]

Since the 1980s there have been efforts to decriminalise Obeah practices throughout many Caribbean countries.[5] However, as of the early 21st century these practices remain widely illegal across the region.[5] Enforcement is often lax and usually only when Obeah practitioners have also infringed on other laws.[5] Most prosecutions center on accusations of charlatanism against Obeah practitioners who have charged large fees and not produced the promised results.[5]

Demographics

Practitioners of Obeah are found across the Caribbean as well as in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom.[4] It is difficult to ascertain the number of clients who employ Obeahmen and Obeahwomen.[4]

Influence

Trinidad had fewer cases of people practicing Obeah than Jamaica. In Trinidad, there was discrimination of what was a religion practice or what was considered Obeah. The reason was the cultural differences of the blacks and East Indian races living in Trinidad and Tobago .[67] The laws pertaining to obeah was derived from the common law system, which governed many islands in the Caribbean like Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago.[68][69]

Literature

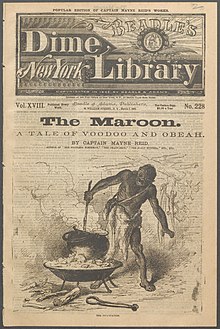

Although 19th-century literature mentions Obeah often, one of the earliest references to Obeah in fiction can be found in 1800, in William Earle's novel Obi; or, The History of Three-Finger'd Jack, a narrative inspired by true events that was also reinterpreted in several dramatic versions on the London stage in 1800 and following.[70] One of the next major books about Obeah was Hamel, the Obeah Man (1827). Several early plantation novels also include Obeah plots. In Marryat's novel Poor Jack (1840) a rich young plantation-owner[71] ridicules superstitions held by English sailors but himself believes in Obeah. The 20th century saw less actual Obeah in open practice, but it still continued to make frequent appearances in literature well into the 21st century, for example, in Leone Ross’s 2021 novel Popisho.

References

Citations

- ^ Maarit Forde and Diana Paton, "Introduction", in Obeah and Other Powers: The Politics of Caribbean Religion and Healing, ed. Diana Paton and Maarit Forde (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012), 10.

- ^ a b Incayawar, Mario; Wintrob, Ronald; Bouchard, Lise; Bartocci, Goffredo (2009). Psychiatrists and Traditional Healers: Unwitting Partners in Global Mental Health. John Wiley and Sons. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-470-51683-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 158.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 179.

- ^ a b c d Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 161.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 164.

- ^ Flores-Peña 2005, p. 117.

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 168.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 170.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 159–160.

- ^ a b c d e Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 160.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 165.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Diana Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah: Religion, Colonialism, and Modernity in the Caribbean World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015), 28.

- ^ Delbourgo, James (2010). "Gardens of life and death". British Journal for the History of Science. 43 (1). British Society for the History of Science: 113–118. doi:10.1017/S0007087410000245. PMID 28974289. S2CID 15256414. Retrieved 2010-07-06.

- ^ Barima (2016). "Cutting Across Space and Time: Obeah's Service to Jamaica's Freedom Struggle in Slavery and Emancipation" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 9 (4). Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Barima (2017). "Obeah to Rastafari: Jamaica as a Colony of Ridicule, Oppression and Violence, 1865-1939" (PDF). Journal of Pan African Studies. 10 (1). Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Obeah Roots

- ^ Nathaniel Samuel Murrell, Obeah: Magical Art of Resistance. In Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2010), 231.

- ^ Chambers, Douglas B. (2009). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-60473-246-7.

- ^ Paton, Cultural Politics, 28.

- ^ Long, Edward (1774). "The History of Jamaica Or, A General Survey of the Antient and Modern State of that Island: With Reflexions on Its Situation, Settlements, Inhabitants, Climate, Products, Commerce, Laws, and Government" (google). 2 (3/4): 445–475.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Mendez, Serafin; Cueto, Gail; Deynes, Neysa Rodríguez (2003). Notable Caribbeans and Caribbean Americans: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313314438.

- ^ Philip Thicknesse, Memoirs and anecdotes of Philip Thicknesse, late lieutenant governor of Land Guard Fort, and unfortunately father to George Touchet, Baron Audley (Dublin: Graisberry and Campbell, 1790), 77.

- ^ Jamaican Assembly, "An Act to remedy the evils arising from irregular assemblies of Slaves, and to prevent their possessing arms and ammunition, and going from place to place without tickets, and for preventing the practice of obeah, and to restrain overseers from leaving the estates under their care on certain days, and to oblige all free negroes, mulattoes or Indians, to register their names in the vestry-books of the respective parishes of this Island, and to carry about them the certificate, and wear the badge of their freedom; and to prevent any captain, master or supercargo of any vessel bringing back Slaves transported off this Island," in CO 139/21, The National Archives.

- ^ Payne-Jackson, Arvilla; Alleyne, Mervyn C.; Alleyne, Mervyn C. (2004). Jamaican Folk Medicine: A Source Of Healing. University of the West Indies Press. ISBN 9789766401238. Retrieved 2019-02-21.

- ^ Konadu, Kwasi (2010). The Akan Diaspora in the Americas. Oxford University Press US. p. 140. ISBN 978-0-19-539064-3.

- ^ a b Rucker, Walter C. (2006). The river flows on: Black resistance, culture, and identity formation in early America. LSU Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-8071-3109-1.

- ^ Eltis, David; Richardson, David (1997). Routes to slavery: direction, ethnicity, and mortality in the transatlantic slave trade. Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 0-7146-4820-5.

- ^ "Obeah". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ^ Chambers, Douglas B. (2009). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia. Univ. Press of Mississippi. pp. 14, 36. ISBN 978-1-60473-246-7.

- ^ Eltis, David; Richardson, David (1997). Routes to slavery: direction, ethnicity, and mortality in the transatlantic slave trade. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 0-7146-4820-5.

- ^ Thomas, M.; Desch-Obi, J. (2008). Fighting for honor: the history of African martial art traditions in the Atlantic world. Univ of South Carolina Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-57003-718-4.

- ^ McCall, John Christensen (2000). Dancing histories: heuristic ethnography with the Ohafia Igbo. University of Michigan Press. p. 148. ISBN 0-472-11070-5.

- ^ a b Paton, Cultural Politics, 29.

- ^ Metcalf, Allan A. (1999). The world in so many words: a country-by-country tour of words that have shaped our language. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 78. ISBN 0-395-95920-9.

- ^ Folklore. Vol. IV. Folklore Society of Great Britain. 1893. pp. 211–212.

- ^ “SUPERSTITION IS THE OFFSPRING OF IGNORANCE,” THE SUPPRESSION OF AFRICAN SPIRITUALITY IN THE BRITISH CARIBBEAN, 1650-1834

- ^ Sharpe, 3.

- ^ Herbert T. Thomas, Untrodden Jamaica (Kingston, Jamaica: A.W. Gardner, 1890), 36.

- ^ Sharpe, 7.

- ^ Kenneth M. Bilby, True Born Maroons (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005), 253.

- ^ Bilby, 211.

- ^ Craton, Michael. Testing the Chains. Cornell University Press, 1982, p. 139.

- ^ Vincent Brown, Tacky's Revolt, p. 213.

- ^ Jones, James Athearn (1831), Haverill, or memoirs of an officer in the army of Wolfe (J.J & Harper), p. 199. ISBN 978-1-1595-9493-0

- ^ Danielle N. Boaz, “‘Instruments of Obeah:’ The Significance of Ritual Objects in the Jamaican Legal System, 1760 to the Present,” in Materialities of Ritual in the Black Atlantic, ed. Akinwumi Ogundiran and Paula Sanders (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2014), 145.

- ^ BECARA, i. e. White Man. "To the Editor of the Universal Register." Times [London, England] 23 Nov. 1787: 1. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ "Mary Seacole, Creole Doctress, Nurse and Healer". 2018-10-21.

- ^ Christer Petley, White Fury: A Jamaican Slaveholder and the Age of Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), pp. 88-9.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 162.

- ^ Matthew G. Lewis, Journal of a West India Proprietor, 1815-1817, Edited with an introduction by Mona Wilson (London: G. Routledge & Sons Ltd., 1929), 149-150.

- ^ Sasha Turner Bryson, “The Art of Power: Poison and Obeah Accusations and the Struggle for Dominance and Survival in Jamaica’s Slave Society,” Caribbean Studies 41, no. 2 (2013): 63.

- ^ "Colonial Intelligence." Times [London, England]. 5 Dec. 1818: 2. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT. "The Outbreak In Jamaica." Times [London, England] 2 Apr. 1866: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 11 June 2012

- ^ "The Obeah men are hired to revenge some man's wrong, while revivalist profess to undo the work of Obeah men and to cure those subject to Obeah alarms." OUR SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT. "The Outbreak In Jamaica." Times [London, England] 2 Apr. 1866: 10. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Randy M. Browne, “The ‘Bad Business’ of Obeah: Power, Authority, and the Politics of Slave Culture in the British Caribbean,” William and Mary Quarterly 68, no. 3 (2011): 451.

- ^ Browne, 469-73.

- ^ In 1818 The Times reported the passing of an act by the House of Assembly in Barbados against the practice of Obeah, which carried the penalty of death or transportation for those convicted. "Colonial Intelligence." Times [London, England] 5 Dec. 1818: 2. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 7 June 2012.

- ^ Rocklin, Alexander (2015). "Obeah and the Politics of Religion's Making and Unmaking in Colonial Trinidad". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 83 (3): 697–721. doi:10.1093/jaarel/lfv022. ISSN 0002-7189.

- ^ "Witchcraft, Witchdoctors and Empire: The Proscription and Prosecution of African Spiritual Practices in British Atlantic Colonies, 1760-1960s".

- ^ Paton, Diana (August 2015). "Obeah in the courts, 1890–1939". The Cultural Politics of Obeah. pp. 158–207. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139198417.006. ISBN 9781139198417. Retrieved 2020-02-26.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Obi

- ^ Described as a 'curly-headed Creole', possibly intended to be mixed-race. F. Marryat, Poor Jack, Chapter XLI.

Sources

- Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (second ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

- Flores-Peña, Ysamur (2005). "Lucumí: The Second Diaspora". In Helen A. Berger (ed.). Witchcraft and Magic: Contemporary North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 102–119. ISBN 978-0812238778.

Further reading

- J. Brent Crosson, Experiments with Power: Obeah and the Remaking of Religion in Trinidad (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020)

- Diana Paton, The Cultural Politics of Obeah: Religion, Colonialism, and Modernity in the Caribbean World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015)

- Payne-Jackson, Arvilla (2004). Jamaican Folk Medicine: A Source of Healing. University of the West Indies Press. ISBN 9766401233.