Sino-Roman relations

| |

China |

SPQR |

|---|---|

Sino-Roman relations comprised the (primarily indirect) contacts and flows of trade goods, information, and occasional travelers between the Roman Empire and the Han dynasty, as well as between the later Eastern Roman Empire and various successive Chinese dynasties that followed. These empires inched progressively closer to each other in the course of the Roman expansion into ancient Western Asia and of the simultaneous Han military incursions into Central Asia. Mutual awareness remained low, and firm knowledge about each other was limited. Surviving records document only a few attempts at direct contact. Intermediate empires such as the Parthians and Kushans, seeking to maintain control over the lucrative silk trade, inhibited direct contact between these two Eurasian powers. In 97 AD the Chinese general Ban Chao tried to send his envoy Gan Ying to Rome, but Parthians dissuaded Gan from venturing beyond the Persian Gulf. Ancient Chinese historians recorded several alleged Roman emissaries to China. The first one on record, supposedly either from the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius or from his adopted son Marcus Aurelius, arrived in 166 AD. Others are recorded as arriving in 226 and 284 AD, followed by a long hiatus until the first recorded Byzantine embassy in 643 AD.

The indirect exchange of goods on land along the Silk Road and sea routes involved (for example) Chinese silk, Roman glassware and high-quality cloth. Roman coins minted from the 1st century AD onwards have been found in China, as well as a coin of Maximian (Roman emperor from 286 to 305 AD) and medallions from the reigns of Antoninus Pius (r. 138–161 AD) and Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 AD) in Jiaozhi (in present-day Vietnam), the same region at which Chinese sources claim the Romans first landed. Roman glassware and silverware have been discovered at Chinese archaeological sites dated to the Han period (202 BC to 220 AD). Roman coins and glass beads have also been found in the Japanese archipelago.[1]

In classical sources, the problem of identifying references to ancient China is exacerbated by the interpretation of the Latin term Seres, whose meaning fluctuated and could refer to several Asian peoples in a wide arc from India over Central Asia to China. In Chinese records, the Roman Empire came to be known as Daqin or Great Qin. Chinese sources directly associated Daqin with the later Fulin (拂菻), which scholars such as Friedrich Hirth have identified as the Byzantine Empire. Chinese sources describe several embassies of Fulin (Byzantine Empire) arriving in China during the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) and also mention the siege of Constantinople by the forces of Muawiyah I in 674–678 AD.

Geographers in the Roman Empire, such as Ptolemy in the second century AD, provided a rough sketch of the eastern Indian Ocean, including the Malay Peninsula and beyond this the Gulf of Thailand and the South China Sea. Ptolemy's "Cattigara" was most likely Óc Eo, Vietnam, where Antonine-era Roman items have been found. Ancient Chinese geographers demonstrated a general knowledge of West Asia and of Rome's eastern provinces. The 7th-century AD Byzantine historian Theophylact Simocatta wrote of China's reunification under the contemporary Sui dynasty (581 to 618 AD), noting that the northern and southern halves were separate nations recently at war. This mirrors both the conquest of Chen by Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604 AD) as well as the names Cathay and Mangi used by later medieval Europeans in China during the Mongol-led Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and the Han Chinese-led Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279).

Geographical accounts and cartography

Roman geography

Beginning in the 1st century BC with Virgil, Horace, and Strabo, Roman historians offer only vague accounts of China and the silk-producing Seres people of the Far East, who were perhaps the ancient Chinese.[2][3] The 1st-century AD geographer Pomponius Mela asserted that the lands of the Seres formed the centre of the coast of an eastern ocean, flanked to the south by India and to the north by the Scythians of the Eurasian Steppe.[2] The 2nd-century AD Roman historian Florus seems to have confused the Seres with peoples of India, or at least noted that their skin complexions proved that they both lived "beneath another sky" than the Romans.[2] Roman authors generally seem to have been confused about where the Seres were located, in either Central Asia or East Asia.[4] The historian Ammianus Marcellinus (c. 330 – c. 400 AD) wrote that the land of the Seres was enclosed by "lofty walls" around a river called Bautis, possibly a description of the Yellow River.[2]

The existence of China was known to Roman cartographers, but their understanding of it was less certain. Ptolemy's 2nd-century AD Geography separates the Land of Silk (Serica) at the end of the overland Silk Road from the land of the Qin (Sinae) reached by sea.[5] The Sinae are placed on the northern shore of the Great Gulf (Magnus Sinus) east of the Golden Peninsula (Aurea Chersonesus, Malay Peninsula). Their chief port, Cattigara, seems to have been in the lower Mekong Delta.[6] The Great Gulf served as a combined Gulf of Tonkin and South China Sea, as Marinus of Tyre and Ptolemy's belief that the Indian Ocean was an inland sea caused them to bend the Cambodian coast south beyond the equator before turning west to join southern Libya (Africa).[7][8] Much of this is given as unknown lands, but the north-eastern area is placed under the Sinae.[9]

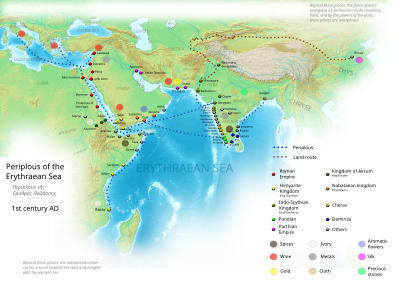

Classical geographers such as Strabo and Pliny the Elder were slow to incorporate new information into their works and, from their positions as esteemed scholars, were seemingly prejudiced against lowly merchants and their topographical accounts.[10] Ptolemy's work represents a break from this, since he demonstrated an openness to their accounts and would not have been able to chart the Bay of Bengal so accurately without the input of traders.[10] In the 1st-century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, its anonymous Greek-speaking author, a merchant of Roman Egypt, provides such vivid accounts of eastern trade cities that it is clear he visited many of them.[11] These include sites in Arabia, Pakistan, and India, including travel times from rivers and towns, where to drop anchor, the locations of royal courts, lifestyles of the locals and goods found in their markets, and favourable times of year to sail from Egypt to these places to catch the monsoon winds.[11] The Periplus also mentions a great inland city, Thinae (or Sinae), in a country called This that perhaps stretched as far as the Caspian.[12][13] The text notes that silk produced there travelled to neighbouring India via the Ganges and to Bactria by a land route.[12] Marinus and Ptolemy had relied on the testimony of a Greek sailor named Alexander, probably a merchant, for how to reach Cattigara (most likely Óc Eo, Vietnam).[6][14] Alexander (Greek: Alexandros) mentions that the main terminus for Roman traders was a Burmese city called Tamala on the north-west Malay Peninsula, where Indian merchants travelled overland across the Kra Isthmus to reach the Perimulic Gulf (the Gulf of Thailand).[15] Alexandros claimed that it took twenty days to sail from Thailand to a port called "Zabia" (or Zaba) in southern Vietnam.[15][16] According to him, one could continue along the coast (of southern Vietnam) from Zabia until reaching the trade port of Cattigara after an unspecified number of days (with "some" being interpreted as "many" by Marinus).[15][16] More generally, modern historical scholars assert that merchants from the Eastern part of the Roman Empire were in contact with the peoples of China, Sri Lanka, India and the Kushana Empire.[17]

Cosmas Indicopleustes, a 6th-century AD Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Greek monk from Alexandria and former merchant with experience in the Indian Ocean trade, was the first Roman to write clearly about China in his Christian Topography (c. 550 AD).[18] He called it the country of Tzinista (comparable to Sanskrit Chinasthana and Syriac Sinistan from the 781 AD Nestorian Stele of Xi'an, China), located in easternmost Asia.[19][20] He explained the maritime route towards it (first sailing east and then north up the southern coast of the Asian continent) and the fact that cloves came that way to Sri Lanka for sale.[19] By the time of the Eastern Roman ruler Justinian I (r. 527–565 AD), the Byzantines purchased Chinese silk from Sogdian intermediaries.[21] They also smuggled silkworms out of China with the help of Nestorian monks, who claimed that the land of Serindia was located north of India and produced the finest silk.[21] By smuggling silkworms and producing silk of their own, the Byzantines could bypass the Chinese silk trade dominated by their chief rivals, the Sasanian Empire.[22]

From Turkic peoples of Central Asia during the Northern Wei (386–535 AD) period the Eastern Romans acquired yet another name for China: Taugast (Old Turkic: Tabghach).[21] Theophylact Simocatta, a historian during the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641 AD), wrote that Taugast (or Taugas) was a great eastern empire colonised by Turkic people, with a capital city 2,400 kilometres (1,500 mi) northeast of India that he called Khubdan (from the Turkic word Khumdan used for the Sui and Tang capital Chang'an), where idolatry was practised but the people were wise and lived by just laws.[23] He depicted the Chinese empire as being divided by a great river (the Yangzi) that served as the boundary between two rival nations at war; during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Maurice (582–602 AD) the northerners wearing "black coats" conquered the "red coats" of the south (black being a distinctive colour worn by the people of Shaanxi, location of the Sui capital Sui Chang'an, according to the 16th-century Persian traveller Hajji Mahomed, or Chaggi Memet).[24] This account may correspond to the conquest of the Chen dynasty and reunification of China by Emperor Wen of Sui (r. 581–604 AD).[24] Simocatta names their ruler as Taisson, which he claimed meant Son of God, either correlating to the Chinese Tianzi (Son of Heaven) or even the name of the contemporary ruler Emperor Taizong of Tang (r. 626–649 AD).[25] Later medieval Europeans in China wrote of it as two separate countries, with Cathay in the north and Mangi in the south, during the period when the Yuan dynasty led by Mongol ruler Kublai Khan (r. 1260–1294 AD) conquered the Southern Song Dynasty.[26][27][28]

Chinese geography

Detailed geographical information about the Roman Empire, at least its easternmost territories, is provided in traditional Chinese historiography. The Shiji by Sima Qian (c. 145–86 BC) gives descriptions of countries in Central Asia and West Asia. These accounts became significantly more nuanced in the Book of Han, co-authored by Ban Gu and his sister Ban Zhao, younger siblings of the general Ban Chao, who led military exploits into Central Asia before returning to China in 102 AD.[29] The westernmost territories of Asia as described in the Book of the Later Han compiled by Fan Ye (398–445 AD) formed the basis for almost all later accounts of Daqin.[29][note 1] These accounts seem to be restricted to descriptions of the Levant, particularly Syria.[29]

Historical linguist Edwin G. Pulleyblank explains that Chinese historians considered Daqin to be a kind of "counter-China" located at the opposite end of their known world.[30][31] According to Pulleyblank, "the Chinese conception of Dà Qín was confused from the outset with ancient mythological notions about the far west".[32][31] From the Chinese point of view, the Roman Empire was considered "a distant and therefore mystical country," according to Krisztina Hoppál.[33] The Chinese histories explicitly related Daqin and Lijian (also "Li-kan", or Syria) as belonging to the same country; according to Yule, D. D. Leslie, and K. H. G. Gardiner, the earliest descriptions of Lijian in the Shiji distinguished it as the Hellenistic-era Seleucid Empire.[34][35][36] Pulleyblank provides some linguistic analysis to dispute their proposal, arguing that Tiaozhi (條支) in the Shiji was most likely the Seleucid Empire and that Lijian, although still poorly understood, could be identified with either Hyrcania in Iran or even Alexandria in Egypt.[37]

The Weilüe by Yu Huan (c. 239–265 AD), preserved in annotations to the Records of the Three Kingdoms (published in 429 AD by Pei Songzhi), also provides details about the easternmost portion of the Roman world, including mention of the Mediterranean Sea.[29] For Roman Egypt, the book explains the location of Alexandria, travelling distances along the Nile and the tripartite division of the Nile Delta, Heptanomis, and Thebaid.[29][38] In his Zhu Fan Zhi, the Song-era Quanzhou customs inspector Zhao Rugua (1170–1228 AD) described the ancient Lighthouse of Alexandria.[39] Both the Book of the Later Han and the Weilüe mention the "flying" pontoon bridge (飛橋) over the Euphrates at Zeugma, Commagene in Roman Anatolia.[29][40] The Weilüe also listed what it considered the most important dependent vassal states of the Roman Empire, providing travel directions and estimates for the distances between them (in Chinese miles, li).[29][38] Friedrich Hirth (1885) identified the locations and dependent states of Rome named in the Weilüe; some of his identifications have been disputed.[note 2] Hirth identified Si-fu (汜復) as Emesa;[29] John E. Hill (2004) uses linguistic and situational evidence to argue it was Petra in the Nabataean Kingdom, which was annexed by Rome in 106 AD during the reign of Trajan.[40]

The Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang record that the Arabs (Da shi 大食) sent their commander Mo-yi (摩拽, pinyin: Móyè, i.e. Muawiyah I, governor of Syria and later Umayyad caliph, r. 661–680 AD) to besiege the Byzantine capital, Constantinople, and forced the Byzantines to pay them tribute.[29] The same books also described Constantinople in some detail as having strong granite walls and a water clock mounted with a golden statue of man.[29][41][42] Henry Yule noted that the name of the Byzantine negotiator "Yenyo" (the patrician John Pitzigaudes) was mentioned in Chinese sources, an envoy who was unnamed in Edward Gibbon's account of the man sent to Damascus to hold a parley with the Umayyads, followed a few years later by the increase of tributary demands on the Byzantines.[43] The New Book of Tang and Wenxian Tongkao described the land of Nubia (either the Kingdom of Kush or Aksum) as a desert south-west of the Byzantine Empire that was infested with malaria, where the natives had black skin and consumed Persian dates.[29] In discussing the three main religions of Nubia (the Sudan), the Wenxian Tongkao mentions the Daqin religion there and the day of rest occurring every seven days for those following the faith of the Da shi (the Muslim Arabs).[29] It also repeats the claim in the New Book of Tang about the Eastern Roman surgical practice of trepanning to remove parasites from the brain.[29] The descriptions of Nubia and Horn of Africa in the Wenxian Tongkao were ultimately derived from the Jingxingji of Du Huan (fl. 8th century AD),[44] a Chinese travel writer whose text, preserved in the Tongdian of Du You, is perhaps the first Chinese source to describe Ethiopia (Laobosa), in addition to offering descriptions of Eritrea (Molin).[45]

Embassies and travel

Prelude

Some contact may have occurred between Hellenistic Greeks and the Qin dynasty in the late 3rd century BC, following the Central Asian campaigns of Alexander the Great, king of Macedon, and the establishment of Hellenistic kingdoms relatively close to China, such as the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Excavations at the burial site of China's first Emperor Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BC) suggest ancient Greeks may have paid tribute and submitted to the supreme universal rule of the Han Chinese Qin dynasty emperor by giving him gifts with Greek stylistic and technological influences in some of the artworks found buried there, including a few examples of the famous terracotta army.[47][48] Cultural exchanges at such an early date are generally regarded as conjectural in academia, but excavations of a 4th-century BC tomb in Gansu province belonging to the state of Qin have yielded Western items such as glass beads and a blue-glazed (possibly faience) beaker of Mediterranean origin.[49] Trade and diplomatic relations between China's Han Empire and remnants of Hellenistic Greek civilization under the rule of the nomadic Da Yuezhi began with the Central Asian journeys of the Han envoy Zhang Qian (d. 113 BC). He brought back reports to the court of Emperor Wu of Han about the "Dayuan" in the Fergana Valley, with Alexandria Eschate as its capital, and the "Daxia" of Bactria, in what is now Afghanistan and Tajikistan.[50] The only well-known Roman traveller to have visited the easternmost fringes of Central Asia was Maes Titianus,[note 3] a contemporary of Trajan in either the late 1st or early 2nd century AD[note 4] who visited a "Stone Tower" that has been identified by historians as either Tashkurgan in the Chinese Pamirs[note 5] or a similar monument in the Alai Valley just west of Kashgar, Xinjiang, China.[51][52][53]

Embassy to Augustus

The historian Florus described the visit of numerous envoys, including the "Seres" (possibly the Chinese) to the court of the first Roman Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC – 14 AD):

Even the rest of the nations of the world which were not subject to the imperial sway were sensible of its grandeur, and looked with reverence to the Roman people, the great conqueror of nations. Thus even Scythians and Sarmatians sent envoys to seek the friendship of Rome. Nay, the Seres came likewise, and the Indians who dwelt beneath the vertical sun, bringing presents of precious stones and pearls and elephants, but thinking all of less moment than the vastness of the journey which they had undertaken, and which they said had occupied four years. In truth it needed but to look at their complexion to see that they were people of another world than ours.[54][55]

In the entire corpus of Roman literature and historiography, Yule was unable to uncover any other mention of such a direct diplomatic encounter between the Romans and the Seres.[note 6] He speculated that these people were more likely to have been private merchants than diplomats, since Chinese records insist that Gan Ying was the first Chinese to reach as far west as Tiaozhi (條支; Mesopotamia) in 97 AD.[note 6] Yule notes that the 1st-century AD Periplus mentioned that people of Thinae (Sinae) were rarely seen, because of the difficulties of reaching that country.[12][13] It states that their country, located under Ursa Minor and on the farthest unknown reaches of the Caspian Sea, was the origin of raw silk and fine silk cloth that was traded overland from Bactria to Barygaza, as well as down the Ganges.[12]

Envoy Gan Ying

The Eastern Han general Ban Chao (32–102 AD), in a series of military successes which brought the Western Regions (the Tarim Basin of Xinjiang) back under Chinese control and suzerainty, defeated the Da Yuezhi in 90 AD and the Northern Xiongnu in 91 AD, forcing the submission of city-states such as Kucha and Turfan, Khotan and Kashgar (Indo-European Tocharian and Saka settlements, respectively),[56] and finally Karasahr in 94 AD.[57][58] An embassy from the Parthian Empire had earlier arrived at the Han court in 89 AD and, while Ban was stationed with his army in Khotan, another Parthian embassy came in 101 AD, this time bringing exotic gifts such as ostriches.[59]

In 97 AD, Ban Chao sent an envoy named Gan Ying to explore the far west. Gan made his way from the Tarim Basin to Parthia and reached the Persian Gulf.[60] Gan left a detailed account of western countries; he apparently reached as far as Mesopotamia, then under the control of the Parthian Empire. He intended to sail to the Roman Empire, but was discouraged when told that the trip was dangerous and could take two years.[61][62] Deterred, he returned to China bringing much new information on the countries to the west of Chinese-controlled territories,[63] as far as the Mediterranean Basin.[60]

Gan Ying is thought to have left an account of the Roman Empire (Daqin in Chinese) which relied on secondary sources—likely sailors in the ports which he visited. The Book of the Later Han locates it in Haixi ("west of the sea", or Roman Egypt;[29][64] the sea is the one known to the Greeks and Romans as the Erythraean Sea, which included the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, and Red Sea):[65]

Its territory extends for several thousands of li [a li during the Han dynasty equalled 415.8 metres].[66] They have established postal relays at intervals, which are all plastered and whitewashed. There are pines and cypresses, as well as trees and plants of all kinds. It has more than four hundred walled towns. There are several tens of smaller dependent kingdoms. The walls of the towns are made of stone.[67]

The Book of the Later Han gives a positive, if inaccurate, view of Roman governance:

Their kings are not permanent rulers, but they appoint men of merit. When a severe calamity visits the country, or untimely rain-storms, the king is deposed and replaced by another. The one relieved from his duties submits to his degradation without a murmur. The inhabitants of that country are tall and well-proportioned, somewhat like the Han [Chinese], whence they are called [Daqin].[68]

Yule noted that although the description of the Roman Constitution and products was garbled, the Book of the Later Han offered an accurate depiction of the coral fisheries in the Mediterranean.[69] Coral was a highly valued luxury item in Han China, imported among other items from India (mostly overland and perhaps also by sea), the latter region being where the Romans sold coral and obtained pearls.[70] The original list of Roman products given in the Book of the Later Han, such as sea silk, glass, amber, cinnabar, and asbestos cloth, is expanded in the Weilüe.[38][71] The Weilüe also claimed that in 134 AD the ruler of the Shule Kingdom (Kashgar), who had been a hostage at the court of the Kushan Empire, offered blue (or green) gems originating from Haixi as gifts to the Eastern Han court.[38] Fan Ye, the editor of the Book of the Later Han, wrote that former generations of Chinese had never reached these far western regions, but that the report of Gan Ying revealed to the Chinese their lands, customs and products.[72] The Book of the Later Han also asserts that the Parthians (Chinese: 安息; Anxi) wished "to control the trade in multi-coloured Chinese silks" and therefore intentionally blocked the Romans from reaching China.[64]

Possible Roman Greeks in Burma and China

It is possible that a group of Greek acrobatic performers, who claimed to be from a place "west of the seas" (Roman Egypt, which the Book of the Later Han related to the Daqin empire), were presented by a king of Burma to Emperor An of Han in 120 AD.[note 7][73][74] It is known that in both the Parthian Empire and Kushan Empire of Asia, ethnic Greeks continued to be employed after the Hellenistic period as musicians and athletes.[75][76] The Book of the Later Han states that Emperor An transferred these entertainers from his countryside residence to the capital Luoyang, where they gave a performance at his court and were rewarded with gold, silver, and other gifts.[77] With regard to the origin of these entertainers, Raoul McLaughlin speculates that the Romans were selling slaves to the Burmese and that this is how the entertainers originally reached Burma before they were sent by the Burmese ruler to Emperor An in China.[78][note 8] Meanwhile, Syrian jugglers were renowned in Western Classical literature,[79] and Chinese sources from the 2nd century BC to the 2nd century AD seem to mention them as well.[80]

First Roman embassy

The first group of people claiming to be an ambassadorial mission of Romans to China was recorded as having arrived in 166 AD by the Book of the Later Han. The embassy came to Emperor Huan of Han China from "Andun" (Chinese: 安敦; Emperor Antoninus Pius or Marcus Aurelius Antoninus), "king of Daqin" (Rome):[81][82]

"... 其王常欲通使於漢,而安息欲以漢繒彩與之交市,故遮閡不得自達。至桓帝延熹九年,大秦王安敦遣使自日南徼外獻象牙、犀角、瑇瑁,始乃一通焉。其所表貢,並無珍異,疑傳者過焉。"

"... The king of this state always wanted to enter into diplomatic relations with the Han. But Parthia ("Anxi") wanted to trade with them in Han silk and so put obstacles in their way, so that they could never have direct relations [with Han]. This continued until the ninth year of the Yanxi (延熹) reign period of Emperor Huan (桓) (A.D. 166), when Andun (安敦), king of Da Qin, sent an envoy from beyond the frontier of Rinan (日南) who offered elephant tusk, rhinoceros horn, and tortoise shell. It was only then that for the first time communication was established [between the two states]."— 《後漢書·西域傳》 “Xiyu Zhuan” of the Hou Hanshu (ch. 88)[83]

As Antoninus Pius died in 161 AD, leaving the empire to his adoptive son Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, and the envoy arrived in 166 AD,[84] confusion remains about who sent the mission, as both emperors were named "Antoninus".[32][85] The Roman mission came from the south (therefore probably by sea), entering China by the frontier of Rinan or Tonkin (present-day Vietnam). It brought presents of rhinoceros horns, ivory, and tortoise shell, probably acquired in Southern Asia.[85][86] The text states that it was the first time there had been direct contact between the two countries.[85] Yule speculated that the Roman visitors must have lost their original wares due to robbery or shipwreck and used the gifts instead, prompting Chinese sources to suspect them of withholding their more precious valuables, which Yule notes was the same criticism directed at papal missionary John of Montecorvino when he arrived in China in the late 13th century AD.[87] Historians Rafe de Crespigny, Peter Fibiger Bang, and Warwick Ball believe that this was most likely a group of Roman merchants rather than official diplomats sent by Marcus Aurelius.[80][81][88] Crespigny stresses that the presence of this Roman embassy as well as others from Tianzhu (in northern India) and Buyeo (in Manchuria) provided much-needed prestige for Emperor Huan, as he was facing serious political troubles and fallout for the forced suicide of politician Liang Ji, who had dominated the Han government well after the death of his sister Empress Liang Na.[89] Yule emphasised that the Roman embassy was said to come by way of Jiaozhi in northern Vietnam, the same route that Chinese sources claimed the embassies from Tianzhu (northern India) had used in 159 and 161 AD.[90]

Other Roman embassies

The Weilüe and Book of Liang record the arrival in 226 AD of a merchant named Qin Lun (秦論) from the Roman Empire (Daqin) at Jiaozhou (Chinese-controlled northern Vietnam).[6][38][80] Wu Miao, the Prefect of Jiaozhi, sent him to the court of Sun Quan (the ruler of Eastern Wu during the Three Kingdoms) in Nanjing,[6][80] where Sun requested that he provide him with a report on his native country and its people.[29][38] An expedition was mounted to return the merchant along with ten female and ten male "blackish coloured dwarfs" he had requested as a curiosity, as well as a Chinese officer, Liu Xian of Huiji (in Zhejiang), who died en route.[29][38][91] According to the Weilüe and Book of Liang Roman merchants were active in Cambodia and Vietnam, a claim supported by modern archaeological finds of ancient Mediterranean goods in the Southeast Asian countries of Vietnam, Thailand, Malaysia, and Indonesia.[6][29][38]

Yule mentions that in the early 3rd century AD a ruler of Daqin sent an envoy with gifts to the northern Chinese court of Cao Wei (220–266 AD) that included glassware of various colours.[92] Several years later a Daqin craftsman is mentioned as showing the Chinese how to make "flints into crystal by means of fire", a curiosity to the Chinese.[92]

Another embassy from Daqin is recorded as bringing tributary gifts to the Chinese Jin Empire (266–420 AD).[80][93] This occurred in 284 AD during the reign of Emperor Wu of Jin (r. 266–290 AD), and was recorded in the Book of Jin, as well as the later Wenxian Tongkao.[29][80] This embassy was presumably sent by the Emperor Carus (r. 282–283 AD), whose brief reign was preoccupied by war with Sasanian Persia.[94]

Fulin: Eastern Roman embassies

Chinese histories for the Tang dynasty (618–907 AD) record contacts with merchants from "Fulin" (拂菻), the new name used to designate the Byzantine Empire.[29][95][96] The first reported diplomatic contact took place in 643 AD during the reigns of Constans II (641–668 AD) and Emperor Taizong of Tang (626–649 AD).[29] The Old Book of Tang, followed by the New Book of Tang, provides the name "Po-to-li" (波多力, pinyin: Bōduōlì) for Constans II, which Hirth conjectured to be a transliteration of Kōnstantinos Pogonatos, or "Constantine the Bearded", giving him the title of a king (王 wáng).[29] Yule[97] and S. A. M. Adshead offer a different transliteration stemming from "patriarch" or "patrician", possibly a reference to one of the acting regents for the 13-year-old Byzantine monarch.[98] The Tang histories record that Constans II sent an embassy in the 17th year of the Zhenguan (貞觀) regnal period (643 AD), bearing gifts of red glass and green gemstones.[29] Yule points out that Yazdegerd III (r. 632–651 AD), last ruler of the Sasanian Empire, sent diplomats to China to secure aid from Emperor Taizong (considered the suzerain over Ferghana in Central Asia) during the loss of the Persian heartland to the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate, which may also have prompted the Byzantines to send envoys to China amid their recent loss of Syria to the Muslims.[99] Tang Chinese sources also recorded how Sasanian prince Peroz III (636–679 AD) fled to Tang China following the conquest of Persia by the growing Islamic caliphate.[98][100]

Yule asserts that the additional Fulin embassies during the Tang period arrived in 711 and 719 AD, with another in 742 AD that may have been Nestorian monks.[101] Adshead lists four official diplomatic contacts with Fulin in the Old Book of Tang as occurring in 643, 667, 701, and 719 AD.[102] He speculates that the absence of these missions in Western literary sources can be explained by how the Byzantines typically viewed political relations with powers of the East, as well as the possibility that they were launched on behalf of frontier officials instead of the central government.[103] Yule and Adshead concur that a Fulin diplomatic mission occurred during the reign of Justinian II (r. 685–695 AD; 705–711 AD). Yule claims it occurred in the year of the emperor's death, 711 AD,[104] whereas Adshead contends that it took place in 701 AD during the usurpation of Leontios and the emperor's exile in Crimea, perhaps the reason for its omission in Byzantine records and the source for confusion in Chinese histories about precisely who sent this embassy.[105] Justinian II regained the throne with the aid of Bulgars and a marriage alliance with the Khazars. Adshead therefore believes a mission sent to Tang China would be consistent with Justinian II's behaviour, especially if he had knowledge of the permission Empress Wu Zetian granted to Narsieh, son of Peroz III, to march against the Arabs in Central Asia at the end of the 7th century.[105]

The 719 AD a Fulin embassy ostensibly came from Leo III the Isaurian (r. 717–741 AD) to the court of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712–756 AD), during a time when the Byzantine emperor was again reaching out to Eastern powers with a renewed Khazar marriage alliance.[106] It also came as Leo III had just defeated the Arabs in 717 CE.[107] The Chinese annals record that "In the first month of the seventh year of the period Kaiyuan [719 CE] their lord [拂菻王, "the King of Fulin"] sent the Ta-shou-ling [an officer of high rank] of T'u-huo-lo [吐火羅, Tokhara] (...) to offer lions and ling-yang [antelopes], two of each. A few months after, he further sent Ta-te-seng ["priests of great virtue"] to our court with tribute."[108] During its long voyage, this embassy probably visited the Turk Shahis king of Afghanistan, since the son of the king took the title "Fromo Kesaro" when he acceded to the throne in 739 CE.[107][109] "Fromo Kesaro" is a phonetic transcription of "Roman Caesar", probably chosen in honor of "Caesar", the title of Leo III, who had defeated their common enemy the Arabs.[107][109][110] In Chinese sources "Fromo Kesaro" was aptly transcribed "Fulin Jisuo" (拂菻罽娑), "Fulin" (拂菻) being the standard Tang Dynasty name for "Byzantine Empire".[111][112][109] The year of this embassy coincided with Xuanzong's refusal to provide aid to the Sogdians of Bukhara and Samarkand against the Arab invasion force.[106] An embassy from the Umayyad Caliphate was received by the Tang court in 732 AD. However, the Arab victory at the 751 AD Battle of Talas and the An Lushan Rebellion crippled Tang Chinese interventionist efforts in Central Asia.[113]

The last diplomatic contacts with Fulin are recorded as having taken place in the 11th century AD. From the Wenxian Tongkao, written by historian Ma Duanlin (1245–1322), and from the History of Song, it is known that the Byzantine emperor Michael VII Parapinakēs Caesar (滅力沙靈改撒, Mie li sha ling kai sa) of Fulin sent an embassy to China's Song dynasty that arrived in 1081 AD, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong of Song (r. 1067–1085 AD).[29][114] The History of Song described the tributary gifts given by the Byzantine embassy as well as the products made in Byzantium. It also described punishments used in Byzantine law, such as the capital punishment of being stuffed into a "feather bag" and thrown into the sea,[29] probably the Romano-Byzantine practice of poena cullei (from Latin 'penalty of the sack').[115] The final recorded embassy arrived in 1091 AD, during the reign of Alexios I Komnenos (r. 1081–1118 AD); this event is only mentioned in passing.[116]

The History of Yuan offers a biography of a Byzantine man named Ai-sie (transliteration of either Joshua or Joseph), who originally served the court of Güyük Khan but later became a head astronomer and physician for the court of Kublai Khan, the Mongol founder of the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368 AD), at Khanbaliq (modern Beijing).[117] He was eventually granted the title Prince of Fulin (拂菻王, Fúlǐn wáng) and his children were listed with their Chinese names, which seem to match with transliterations of the Christian names Elias, Luke, and Antony.[117] Kublai Khan is also known to have sent Nestorian monks, including Rabban Bar Sauma, to the court of Byzantine ruler Andronikos II Palaiologos (r. 1282–1328 AD), whose half-sisters were married to the great-grandsons of Genghis Khan, making this Byzantine ruler an in-law with the Mongol ruler in Beijing.[118]

Right: A Western Han (202 BC – 9 AD) blue-glass bowl; the Chinese had been making glass beads based on imports from West Asia since the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC), and the first Chinese glassware appeared during the Western Han era.[119]

Within the Mongol Empire, which eventually included all of China, there were enough Westerners travelling there that in 1340 AD Francesco Balducci Pegolotti compiled a guide book for fellow merchants on how to exchange silver for paper money to purchase silk in Khanbaliq (Beijing).[120] By this stage the Eastern Roman Empire, temporarily dismantled by the Latin Empire, had shrunk to the size of a rump state in parts of Greece and Anatolia.[121][122] Ma Duanlin, author of the Wenxian Tongkao, noted the shifting political boundaries, albeit based on generally inaccurate and distorted political geography.[29] He wrote that historians of the Tang Dynasty considered "Daqin" and "Fulin" to be the same country, but he had his reservations about this due to discrepancies in geographical accounts and other concerns (Wade–Giles spelling):

During the sixth year of Yuan-yu [1091] they sent two embassies, and their king was presented, by Imperial order, with 200 pieces of cloth, pairs of silver vases, and clothing with gold bound in a girdle. According to the historians of the T'ang dynasty, the country of Fulin was held to be identical with the ancient Ta-ts'in. It should be remarked, however, that, although Ta-ts'in has from the Later Han dynasty when Zhongguo was first communicated with, till down to the Chin and T'ang dynasties has offered tribute without interruption, yet the historians of the "four reigns" of the Sung dynasty, in their notices of Fulin, hold that this country has not sent tribute to court up to the time of Yuan-feng [1078–1086] when they sent their first embassy offering local produce. If we, now, hold together the two accounts of Fulin as transmitted by the two different historians, we find that, in the account of the T'ang dynasty, this country is said "to border on the great sea in the west"; whereas the Sung account says that "in the west you have still thirty days' journey to the sea;" and the remaining boundaries do also not tally in the two accounts; nor do the products and the customs of the people. I suspect that we have before us merely an accidental similarity of the name, and that the country is indeed not identical with Ta-ts'in. I have, for this reason, appended the Fulin account of the T'ang dynasty to my chapter on Ta-ts'in, and represented this Fulin of the Sung dynasty as a separate country altogether.[123]

The History of Ming expounds how the Hongwu Emperor, founder of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD), sent a merchant of Fulin named "Nieh-ku-lun" (捏古倫) back to his native country with a letter announcing the founding of the Ming dynasty.[29][124][125] It is speculated that the merchant was a former archbishop of Khanbaliq called Nicolaus de Bentra (who succeeded John of Montecorvino for that position).[29][126] The History of Ming goes on to explain that contacts between China and Fulin ceased after this point and an envoy of the great western sea (the Mediterranean Sea) did not appear in China again until the 16th century AD, with the 1582 AD arrival of the Italian Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci in Portuguese Macau.[29][note 9]

Trade relations

Roman exports to China

Direct trade links between the Mediterranean lands and India had been established in the late 2nd century BC by the Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt.[127] Greek navigators learned to use the regular pattern of the monsoon winds for their trade voyages in the Indian Ocean. The lively sea trade in Roman times is confirmed by the excavation of large deposits of Roman coins along much of the coast of India. Many trading ports with links to Roman communities have been identified in India and Sri Lanka along the route used by the Roman mission.[128] Archaeological evidence stretching from the Red Sea ports of Roman Egypt to India suggests that Roman commercial activity in the Indian Ocean and Southeast Asia declined heavily with the Antonine Plague of 166 AD, the same year as the first Roman embassy to Han China, where similar plague outbreaks had occurred from 151 AD.[129][130]

High-quality glass from Roman manufacturers in Alexandria and Syria was exported to many parts of Asia, including Han China.[131][33] The first Roman glassware discovered in China is a blue soda-lime glass bowl dating to the early 1st century BC and excavated from a Western Han tomb in the southern port city of Guangzhou, which may have come there via the Indian Ocean and South China Sea.[132] Other Roman glass items include a mosaic-glass bowl found in a prince's tomb near Nanjing dated to 67 AD and a glass bottle with opaque white streaks found in an Eastern Han tomb of Luoyang.[133] Roman and Persian glassware has been found in a 5th-century AD tomb of Gyeongju, Korea, capital of ancient Silla, east of China.[134] Roman glass beads have been discovered as far as Japan, within the 5th-century AD Kofun-era Utsukushi burial mound near Kyoto.[135]

From Chinese sources it is known that other Roman luxury items were esteemed by the Chinese. These include gold-embroidered rugs and gold-coloured cloth, amber, asbestos cloth, and sea silk, which was a cloth made from the silk-like hairs of a Mediterranean shellfish, the Pinna nobilis.[29][136][137][138] As well as silver and bronze items found throughout China dated to the 3rd–2nd centuries BC and perhaps originating from the Seleucid Empire, there is also a Roman gilded silver plate dated to the 2nd–3rd centuries AD and found in Jingyuan County, Gansu, with a raised relief image in the centre depicting the Greco-Roman god Dionysus resting on a feline creature.[139]

A maritime route opened up with the Chinese-controlled port of Rinan in Jiaozhi (centred in modern Vietnam) and the Khmer kingdom of Funan by the 2nd century AD, if not earlier.[140][141] Jiaozhi was proposed by Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 to have been the port known to the Greco-Roman geographer Ptolemy as Cattigara, situated near modern Hanoi.[142] Ptolemy wrote that Cattigara lay beyond the Golden Chersonese (the Malay Peninsula) and was visited by a Greek sailor named Alexander, most likely a merchant.[6] Richthofen's identification of Cattigara as Hanoi was widely accepted until archaeological discoveries at Óc Eo (near Ho Chi Minh City) in the Mekong Delta during the mid-20th century suggested this may have been its location.[note 10] At this place, which was once located along the coastline, Roman coins were among the vestiges of long-distance trade discovered by the French archaeologist Louis Malleret in the 1940s.[140] These include Roman golden medallions from the reigns of Antoninus Pius and his successor Marcus Aurelius.[6][143] Furthermore, Roman goods and native jewellery imitating Antonine Roman coins have been found there, and Granville Allen Mawer states that Ptolemy's Cattigara seems to correspond with the latitude of modern Óc Eo.[14][note 11] In addition, Ancient Roman glass beads and bracelets were also found at the site.[143]

The trade connection from Cattigara extended, via ports on the coasts of India and Sri Lanka, all the way to Roman-controlled ports in Egypt and the Nabataean territories on the north-eastern coast of the Red Sea.[144] The archaeologist Warwick Ball does not consider discoveries such as the Roman and Roman-inspired goods at Óc Eo, a coin of Roman emperor Maximian found in Tonkin, and a Roman bronze lamp at P'ong Tuk in the Mekong Delta, to be conclusive proof that Romans visited these areas and suggests that the items could have been introduced by Indian merchants.[145] While observing that the Romans had a recognised trading port in Southeast Asia, Dougald O'Reilly writes that there is little evidence to suggest Cattigara was Óc Eo. He argues that the Roman items found there only indicate that the Indian Ocean trade network extended to the ancient Kingdom of Funan.[143]

Chinese silk in the Roman Empire

Chinese trade with the Roman Empire, confirmed by the Roman desire for silk, started in the 1st century BC. The Romans knew of wild silk harvested on Cos (coa vestis), but they did not at first make the connection with the silk that was produced in the Pamir Sarikol kingdom.[146] There were few direct trade contacts between Romans and Han Chinese, as the rival Parthians and Kushans were each protecting their lucrative role as trade intermediaries.[147][148]

During the 1st century BC silk was still a rare commodity in the Roman world; by the 1st century AD this valuable trade item became much more widely available.[149] In his Natural History (77–79 AD), Pliny the Elder lamented the financial drain of coin from the Roman economy to purchase this expensive luxury. He remarked that Rome's "womankind" and the purchase of luxury goods from India, Arabia, and the Seres of the Far East cost the empire roughly 100 million sesterces per year,[150] and claimed that journeys were made to the Seres to acquire silk cloth along with pearl diving in the Red Sea.[151][138] Despite the claims by Pliny the Elder about the trade imbalance and quantity of Rome's coinage used to purchase silk, Warwick Ball asserts that the Roman purchase of other foreign commodities, particularly spices from India, had a much greater impact on the Roman economy.[152] In 14 AD the Senate issued an edict prohibiting the wearing of silk by men, but it continued to flow unabated into the Roman world.[149] Beyond the economic concerns that the import of silk caused a huge outflow of wealth, silk clothes were also considered to be decadent and immoral by Seneca the Elder:

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes ... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body.

— Seneca the Elder c. 3 BC – 65 AD, Excerpta Controversiae 2.7[153]

Trade items such as spice and silk had to be paid for with Roman gold coinage. There was some demand in China for Roman glass; the Han Chinese also produced glass in certain locations.[154][149] Chinese-produced glassware date back to the Western Han era (202 BC – 9 AD).[155] In dealing with foreign states such as the Parthian Empire, the Han Chinese were perhaps more concerned with diplomatically outmaneuvering their chief enemies, the nomadic Xiongnu, than with establishing trade, since mercantile pursuits and the merchant class were frowned upon by the gentry who dominated the Han government.[156]

Roman and Byzantine currency discovered in China

Valerie Hansen wrote in 2012 that no Roman coins from the Roman Republic (509–27 BC) or the Principate (27 BC – 284 AD) era of the Roman Empire have been found in China.[157] Nevertheless, Warwick Ball (2016) cites two studies from 1978 summarizing the discovery at Xi'an, China (the site of the Han capital Chang'an) of a hoard of sixteen Roman coins from the reigns of Tiberius (14–37 AD) to Aurelian (270–275 AD).[152] The Roman coins found at Óc Eo, Vietnam, near Chinese-controlled Jiaozhou, date to the mid-2nd century AD.[6][143] A coin of Maximian (r. 286–305 AD) was also discovered in Tonkin.[145] As a note, Roman coins of the 3rd and 4th centuries AD have been discovered in Japan; they were unearthed from Katsuren Castle (in Uruma, Okinawa), which was built from the 12th to 15th centuries AD.[158]

Shortly after the smuggling of silkworm eggs into the Byzantine Empire from China by Nestorian Christian monks, the 6th-century AD Byzantine historian Menander Protector wrote of how the Sogdians attempted to establish a direct trade of Chinese silk with the Byzantine Empire. After forming an alliance with the Sasanian Persian ruler Khosrow I to defeat the Hephthalite Empire, Istämi, the Göktürk ruler of the First Turkic Khaganate, was approached by Sogdian merchants requesting permission to seek an audience with the Sasanian king of kings for the privilege of travelling through Persian territories to trade with the Byzantines.[159] Istämi refused the first request, but when he sanctioned the second one and had the Sogdian embassy sent to the Sasanian king, the latter had the members of the embassy killed by poison.[159] Maniakh, a Sogdian diplomat, convinced Istämi to send an embassy directly to Byzantium's capital Constantinople, which arrived in 568 AD and offered not only silk as a gift to Byzantine ruler Justin II, but also an alliance against Sasanian Persia. Justin II agreed and sent an embassy under Zemarchus to the Turkic Khaganate, ensuring the direct silk trade desired by the Sogdians.[159][160][161] The small number of Roman and Byzantine coins found during excavations of Central Asian and Chinese archaeological sites from this era suggests that direct trade with the Sogdians remained limited. This was despite the fact that ancient Romans imported Han Chinese silk,[162] and discoveries in contemporary tombs indicate that the Han-dynasty Chinese imported Roman glassware.[163]

The earliest gold solidus coins from the Eastern Roman Empire found in China date to the reign of Byzantine emperor Theodosius II (r. 408–450 AD) and altogether only forty-eight of them have been found (compared to 1300 silver coins) in Xinjiang and the rest of China.[157] The use of silver coins in Turfan persisted long after the Tang campaign against Karakhoja and Chinese conquest of 640 AD, with a gradual adoption of Chinese bronze coinage during the 7th century AD.[157] Hansen maintains that these Eastern Roman coins were almost always found with Sasanian Persian silver coins and Eastern Roman gold coins were used more as ceremonial objects like talismans, confirming the pre-eminence of Greater Iran in Chinese Silk Road commerce of Central Asia compared to Eastern Rome.[164] Walter Scheidel remarks that the Chinese viewed Byzantine coins as pieces of exotic jewellery, preferring to use bronze coinage in the Tang and Song dynasties, as well as paper money during the Song and Ming periods, even while silver bullion was plentiful.[165] Ball writes that the scarcity of Roman and Byzantine coins in China, and the greater amounts found in India, suggest that most Chinese silk purchased by the Romans was from maritime India, largely bypassing the overland Silk Road trade through Iran.[152] Chinese coins from the Sui and Tang dynasties (6th–10th centuries AD) have been discovered in India; significantly larger amounts are dated to the Song period (11th–13th centuries AD), particularly in the territories of the contemporary Chola dynasty.[166]

Even with the Byzantine production of silk starting in the 6th century AD, Chinese varieties were still considered to be of higher quality.[22] This theory is supported by the discovery of a Byzantine solidus minted during the reign of Justin II found in a Sui-dynasty tomb of Shanxi province in 1953, among other Byzantine coins found at various sites.[22] Chinese histories offer descriptions of Roman and Byzantine coins. The Weilüe, Book of the Later Han, Book of Jin, as well as the later Wenxian Tongkao noted how ten ancient Roman silver coins were worth one Roman gold coin.[29][38][69][167] The Roman golden aureus was worth about twenty-five silver denarii.[168] During the later Byzantine Empire, twelve silver miliaresion was equal to one gold nomisma.[169] The History of Song notes that the Byzantines made coins of either silver or gold, without holes in the middle, with an inscription of the king's name.[29] It also asserts that the Byzantines forbade the production of counterfeit coins.[29]

Human remains

In 2010, mitochondrial DNA was used to identify that a partial skeleton found in a Roman cemetery from the 1st or 2nd century AD in Vagnari, Italy, had East Asian ancestry on his mother's side. Evidence indicated that he was not originally from Italy, and was a slave or worker in the area.[170][171]

A 2016 analysis of archaeological finds from Southwark in London, the site of the ancient Roman city Londinium in Roman Britain, suggests that two or three skeletons from a sample of twenty-two dating to the 2nd to the 4th centuries AD are of Asian ancestry, and possibly of Chinese descent. The assertion is based on forensics and the analysis of skeletal facial features. The discovery has been presented by Dr Rebecca Redfern, curator of human osteology at the Museum of London.[172][173] No DNA analysis has yet been done, the skull and tooth samples available offer only fragmentary pieces of evidence, and the samples that were used were compared with the morphology of modern populations, not ancient ones.[174]

Hypothetical military contact

The historian Homer H. Dubs speculated in 1941 that Roman prisoners of war who were transferred to the eastern border of the Parthian Empire might later have clashed with Han troops there.[175]

After a Roman army under the command of Marcus Licinius Crassus decisively lost the battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, an estimated 10,000 Roman prisoners were dispatched by the Parthians to Margiana to man the frontier. Some time later the nomadic Xiongnu chief Zhizhi established a state further east in the Talas valley, near modern-day Taraz. Dubs points to a Chinese account by Ban Gu of about "a hundred men" under the command of Zhizhi who fought in a so-called "fish-scale formation" to defend Zhizhi's wooden-palisade fortress against Han forces, in the Battle of Zhizhi in 36 BC. He claimed that this might have been the Roman testudo formation and that these men, who were captured by the Chinese, founded the village of Liqian (Li-chien, possibly from "legio") in Yongchang County.[176][177]

There have been attempts to promote the Sino-Roman connection for tourism, but Dubs' synthesis of Roman and Chinese sources has not found acceptance among historians, on the grounds that it is highly speculative and reaches too many conclusions without sufficient hard evidence.[178][179] DNA testing in 2005 confirmed the Indo-European ancestry of a few inhabitants of modern Liqian; this could be explained by transethnic marriages with Indo-European people known to have lived in Gansu in ancient times,[180][181] such as the Yuezhi and Wusun. A much more comprehensive DNA analysis of more than two hundred male residents of the village in 2007 showed close genetic relation to the Han Chinese populace and great deviation from the Western Eurasian gene pool.[182] The researchers conclude that the people of Liqian are probably of Han Chinese origin.[182] The area lacks archaeological evidence of a Roman presence, such as coins, pottery, weaponry, architecture, etc.[180][181]

See also

- China–Greece relations

- China–Italy relations

- China–European Union relations

- Comparative studies of the Roman and Han empires

- Malay Chronicles: Bloodlines and Dragon Blade, films based on Sino-Roman relations

- Ancient Greece–Ancient India relations

Notes

- ^ For the assertion that the first Chinese mention of Daqin belongs to the Book of the Later Han, see: Wilkinson (2000), p. 730.

- ^ Hirth (2000) [1885], "From the Wei-lio (written before 429 C.E.), for 220–264 C.E.", (using Wade-Giles) identified these dependent vassal states as Alexandria-Euphrates or Charax Spasinu ("Ala-san"), Nikephorium ("Lu-fen"), Palmyra ("Ch'ieh-lan"), Damascus ("Hsien-tu"), Emesa ("Si-fu"), and Hira ("Ho-lat"). Going south of Palmyra and Emesa led one to the "Stony Land", which Hirth identified as Arabia Petraea, due to the text speaking how it bordered a sea (the Red Sea) where corals and real pearls were extracted. The text also explained the positions of border territories that were controlled by Parthia, such as Seleucia ("Si-lo").

Hill (September 2004), "Section 14 – Roman Dependencies", identified the dependent vassal states as Azania (Chinese: 澤散; pinyin: Zesan; Wade–Giles: Tse-san), Al Wajh (Chinese: 驢分; pinyin: Lüfen; Wade–Giles: Lü-fen), Wadi Sirhan (Chinese: 且蘭; pinyin: Qielan; Wade–Giles: Ch'ieh-lan), Leukos Limên, ancient site controlling the entrance to the Gulf of Aqaba near modern Aynūnah (Chinese: 賢督; pinyin: Xiandu; Wade–Giles: Hsien-tu), Petra (Chinese: 汜復; pinyin: Sifu; Wade–Giles: Szu-fu), al-Karak (Chinese: 于羅; pinyin: Yuluo; Wade–Giles: Yü-lo), and Sura (Chinese: 斯羅; pinyin: Siluo; Wade–Giles: Szu-lo). - ^ His "Macedonian" origin betokens no more than his cultural affinity, and the name Maës is Semitic in origin, Cary (1956), p. 130.

- ^ The mainstream opinion, noted by Cary (1956), p. 130, note #7, based on the date of Marinus of Tyre, established by his use of many Trajanic foundation names but none identifiable with Hadrian.

- ^ Centuries later Tashkurgan ("Stone Tower") was the capital of the Pamir kingdom of Sarikol.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 18; for a discussion of Tiaozhi (条支) and even its etymology possibly stemming from the Tajiks and Iranian peoples under ancient Chinese rule, see footnote #2 on p. 42.

- ^ a b Fan Ye, ed. (1965) [445]. "86: 南蠻西南夷列傳 (Nanman, Xinanyi liezhuan: Traditions of the Southern Savages and South-Western Tribes)". 後漢書 [Book of the Later Han]. Beijing: Zhonghua Publishing. p. 2851. "永寧元年,撣國王雍由調復遣使者詣闕朝賀,獻樂及幻人,能變化吐火,自支解,易牛馬頭。又善跳丸, 數乃至千。自言我海西人。海西即大秦也,撣國西南通大秦。明年元會,安帝作樂於庭,封雍由調爲漢大都尉,賜印綬、金銀、綵繒各有差也。"

A translation of this passage into English, in addition to an explanation of how Greek athletic performers figured prominently in the neighbouring Parthian and Kushan Empires of Asia, is offered by Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 40–41:The first year of Yongning (120 AD), the southwestern barbarian king of the kingdom of Chan (Burma), Yongyou, proposed illusionists (jugglers) who could metamorphose themselves and spit out fire; they could dismember themselves and change an ox head into a horse head. They were very skilful in acrobatics and they could do a thousand other things. They said that they were from the "west of the seas" (Haixi–Egypt). The west of the seas is the Daqin (Rome). The Daqin is situated to the south-west of the Chan country. During the following year, Andi organized festivities in his country residence and the acrobats were transferred to the Han capital where they gave a performance to the court, and created a great sensation. They received the honours of the Emperor, with gold and silver, and every one of them received a different gift.

- ^ Raoul McLaughlin notes that the Romans knew Burma as India Trans Gangem (India Beyond the Ganges) and that Ptolemy listed the cities of Burma. See McLaughlin (2010), p. 58.

- ^ For information on Matteo Ricci and reestablishment of Western contact with China by the Portuguese Empire during the Age of Discovery, see: Fontana (2011), pp. 18–35, 116–118.

- ^ For a summary of scholarly debate about the possible locations of Cattigara by the end of the 20th century, with proposals ranging from Guangzhou, Hanoi, and the Mekong River Delta of the Kingdom of Funan, see: Suárez (1999), p. 92.

- ^ Mawer also mentions Kauthara (in Khánh Hòa Province, Vietnam) and Kutaradja (Banda Aceh, Indonesia) as other plausible sites for that port. Mawer (2013), p. 38.

References

Citations

- ^ a b British Library. "Detailed record for Harley 7182". www.bl.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Ostrovsky (2007), p. 44.

- ^ Lewis (2007), p. 143.

- ^ Schoff (1915), p. 237.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 1–2, 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Young (2001), p. 29.

- ^ Raoul McLaughlin (2010), pp. 58–59.

- ^ Suárez (1999), p. 92.

- ^ Wilford (2000), p. 38; Encyclopaedia Britannica (1903), p. 1540.

- ^ a b Parker (2008), p. 118.

- ^ a b Schoff (2004) [1912], Introduction. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b c d Schoff (2004) [1912], Paragraph #64. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), footnote #2 on p. 43.

- ^ a b Mawer (2013), p. 38.

- ^ a b c McLaughlin (2014), p. 205.

- ^ a b Suárez (1999), p. 90.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2021). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 230.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 25.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 28.

- ^ Lieu (2009), p. 227.

- ^ a b c Luttwak (2009), p. 168.

- ^ a b c Luttwak (2009), pp. 168–169.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 29–31; footnote #3 on p. 31.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 30; footnote #2 on p. 30.

- ^ Yule (1915), p 29; footnote #4 on p. 29.

- ^ Haw (2006), pp. 170–171.

- ^ Wittfogel & Feng (1946), p. 2.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag Friedrich Hirth (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham University. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), p. 71.

- ^ a b See also Lewis (2007), p. 143.

- ^ a b Pulleyblank (1999), p. 78.

- ^ a b Hoppál, Krisztina (2019). "Chinese Historical Records and Sino-Roman Relations: A Critical Approach to Understand Problems on the Chinese Reception of the Roman Empire". RES Antiquitatis. 1: 63–81.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 41; footnote #4.

- ^ For a review of The Roman Empire as Known to Han China: The Roman Empire in Chinese Sources by D. D. Leslie; K. H. J. Gardiner, see Pulleyblank (1999), pp 71–79; for the specific claim about "Li-Kan" or Lijian see Pulleyblank (1999), p 73.

- ^ Fan, Ye (September 2003). Hill, John E. (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices): Section 11 – The Kingdom of Daqin 大秦 (the Roman Empire)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), pp 73–77; Lijian's identification as Hyrcania was put forward by Marie-Félicité Brosset (1828) and accepted by Markwart, De Groot, and Herrmann (1941). Paul Pelliot advanced the theory that Lijian was a transliteration of Alexandria in Roman Egypt.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Yu, Huan (September 2004). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 AD". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Archived from the original on 15 March 2005. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Needham (1971), p. 662.

- ^ a b Yu, Huan (September 2004). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Peoples of the West from the Weilue 魏略 by Yu Huan 魚豢: A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265, Quoted in zhuan 30 of the Sanguozhi, Published in 429 CE: Section 11 – Da Qin (Roman territory/Rome)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 46–48.

- ^ Ball (2016), pp. 152–153; see also endnote #114.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 48–49; for a brief summary of Gibbon's account, see also footnote #1 on p. 49.

- ^ Bai (2003), pp 242–247.

- ^ Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa Archived 2017-08-02 at the Wayback Machine ". New African. Accessed 2 August 2017.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 15–16.

- ^ "BBC Western contact with China began long before Marco Polo, experts say". BBC News. 12 October 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Montgomery, Stephanie; Cammack, Marcus (12 October 2016). "The Mausoleum of China's First Emperor Partners with the BBC and National Geographic Channel to Reveal Groundbreaking Evidence That China Was in Contact with the West During the Reign of the First Emperor". Press release. Business Wire. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ Sun (July 2009), p. 7.

- ^ Yang, Juping. “Hellenistic Information in China.” CHS Research Bulletin 2, no. 2 (2014). http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:YangJ.Hellenistic_Information_in_China.2014.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. xiii, 396,

- ^ Stein (1907), pp. 44–45.

- ^ Stein (1933), pp. 47, 292–295.

- ^ Florus, as quoted in Yule (1915), p. 18; footnote #1.

- ^ Florus, Epitome, II, 34

- ^ Tremblay (2007), p. 77.

- ^ Crespigny (2007), p. 590.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 40.

- ^ Crespigny (2007), pp. 590–591.

- ^ a b Crespigny (2007), pp. 239–240.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 5.

- ^ Pulleyblank (1999), pp. 77–78.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. 5, 481–483.

- ^ a b Fan, Ye (September 2003). John E. Hill (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Hill (2009), pp. 23, 25.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. xx.

- ^ Book of the Later Han, as quoted in Hill (2009), pp. 23, 25.

- ^ Book of the Later Han, as quoted in Hirth (2000) [1885], online source, retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), pp. 43–44.

- ^ Kumar (2005), pp. 61–62.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 25.

- ^ Hill, John E. (2012) Through the Jade Gate: China to Rome 2nd edition, p. 55. In press.

- ^ McLaughlin (2014), pp. 204–205.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 52–53.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), pp. 40–41.

- ^ Cumont (1933), pp. 264–68.

- ^ Christopoulos (August 2012), p. 41.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 58.

- ^ Braun (2002), p. 260.

- ^ a b c d e f Ball (2016), p. 152.

- ^ a b de Crespigny (2007), p. 600.

- ^ Yü (1986), pp. 460–461.

- ^ Translation in YU, Taishan (Chinese Academy of Social Sciences) (2013). "China and the Ancient Mediterranean World: A Survey of Ancient Chinese Sources". Sino-Platonic Papers. 242: 25–26. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.698.1744..

Chinese original: "Chinese Text Project Dictionary". ctext.org. - ^ "The First Contact Between Rome and China - Silk-Road.com". Silk Road. Retrieved 2021-06-29.

- ^ a b c Hill (2009), p. 27.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 27 and nn. 12.18 and 12.20.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 51–52.

- ^ Bang (2009), p. 120.

- ^ de Crespigny. (2007), pp. 597–600.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 52.

- ^ Hirth (1885), pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b Yule (1915), p. 53; see footnotes #4–5.

- ^ "During the Taikang Era (280-289) of the reign of Wudi (r.266-290), their King sent an Embassy with tribute" (武帝太康中,其王遣使貢獻) in the account of Daqin (大秦國) in "晉書/卷097". zh.wikisource.org.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 53–54.

- ^ Wilkinson (2000), p. 730, footnote #14.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 55–57.

- ^ Yule (1915), footnote #2 of pp. 54–55.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 105.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 54–55.

- ^ Schafer (1985), pp. 10, 25–26.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 55–56.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], pp. 104–106.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 104.

- ^ Yule (1915), p. 55.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995), pp. 105–106.

- ^ a b Adshead (1995) [1988], p. 106.

- ^ a b c Kim, Hyun Jin (19 November 2015). The Huns. Routledge. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-1-317-34090-4.

- ^ Old Book of Tang (舊唐書 Jiu Tangshu), ch. 198 (written mid-10th Century C.E.), for 618–906 C.E: "開元七年正月,其主遣吐火羅大首領獻獅子、羚羊各二。不數月,又遣大德僧來朝貢" quoted in English translation in Hirth, F. (1885). China and the Roman Orient: Researches into their Ancient and Mediaeval Relations as Represented in Old Chinese Records. Shanghai & Hong Kong.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Piras, Andrea (2013). "FROMO KESARO. Echi del prestigio di Bisanzio in Asia Centrale". Polidoro. Studi offerti ad Antonio Carile (in Italian). Spoleto: Centro italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo: 681.

- ^ Martin, Dan (2011). "Greek and Islamic Medicines' Historic Contact with Tibet". In Anna Akasoy; Charles Burnett; Ronit Yoeli-Tlalim (eds.). Islam and Tibet – Interactions along the Musk Routes. p. 127.

He received this laudatory epithet because he, like the Byzantines, was successful at holding back the Muslim conquerors.

- ^ Rahman, Abdur (2002). New Light on Khingal, Turk and Hindu Shahis (PDF). Vol. XV. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols. pp. 37–41. ISBN 2-503-51681-5.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ Balogh, Dániel (12 March 2020). Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis. p. 106. ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

- ^ Adshead (1995) [1988], pp. 106–107.

- ^ Sezgin (1996), p. 25.

- ^ Bauman (2005), p. 23.

- ^ Yule (1915), pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Bretschneider (1888), p. 144.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), p. 169.

- ^ An, (2002), pp. 79, 82–83.

- ^ Spielvogel (2011), p. 183.

- ^ Jacobi (1999), pp. 525–542.

- ^ Reinert (2002), pp. 257–261.

- ^ Wenxian Tongkao, as quoted in Hirth (2000) [1885], online source, retrieved 10 September 2016; in this passage, "Ta-ts'in" is an alternate spelling of "Daqin", the former using the Wade–Giles spelling convention and the latter using pinyin.

- ^ Grant (2005), p. 99.

- ^ Hirth (1885), p. 66.

- ^ Luttwak (2009), p. 170.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 25.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), pp. 34–57.

- ^ de Crespigny. (2007), pp. 514, 600.

- ^ McLaughlin (2010), p. 58–60.

- ^ An (2002), p. 82.

- ^ An (2002), p. 83.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 83–84.

- ^ Lee, Hee Soo (7 June 2014). "1,500 Years of Contact between Korea and the Middle East". Middle East Institute. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ^ "Japanese Tomb Found To House Rare Artifacts From Roman Empire". Huffington Post. 27 June 2012. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ Thorley (1971), pp. 71–80.

- ^ Hill (2009), Appendix B – Sea Silk, pp. 466–476.

- ^ a b Lewis (2007), p. 115.

- ^ Harper (2002), pp. 99–100, 106–107.

- ^ a b Osborne (2006), pp. 24–25.

- ^ Hill (2009), p. 291.

- ^ Ferdinand von Richthofen, China, Berlin, 1877, Vol.I, pp. 504–510; cited in Richard Hennig,Terrae incognitae : eine Zusammenstellung und kritische Bewertung der wichtigsten vorcolumbischen Entdeckungsreisen an Hand der daruber vorliegenden Originalberichte, Band I, Altertum bis Ptolemäus, Leiden, Brill, 1944, pp. 387, 410–411; cited in Zürcher (2002), pp. 30–31.

- ^ a b c d O'Reilly (2007), p. 97.

- ^ Young (2001), pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Ball (2016), p. 153.

- ^ Schoff (1915), p. 229.

- ^ Thorley (1979), pp. 181–190 (187f.).

- ^ Thorley (1971), pp. 71–80 (76).

- ^ a b c Whitfield (1999), p. 21.

- ^ "India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us. For what fraction of these imports is intended for sacrifices to the gods or the spirits of the dead?" Original Latin: "minimaque computatione miliens centena milia sestertium annis omnibus India et Seres et paeninsula illa imperio nostro adimunt: tanti nobis deliciae et feminae constant. quota enim portio ex illis ad deos, quaeso, iam vel ad inferos pertinet?" Pliny, Historia Naturae 12.41.84.

- ^ Natural History (Pliny), as quoted in Whitfield (1999), p. 21.

- ^ a b c Ball (2016), p. 154.

- ^ Seneca (1974), p. 375.

- ^ a b Ball (2016), pp. 153–154.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 82–83.

- ^ Ball (2016), p. 155.

- ^ a b c Hansen (2012), p. 97.

- ^ "Ancient Roman coins unearthed from castle ruins in Okinawa". The Japan Times. 26 September 2016. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Howard (2012), p. 133.

- ^ Liu (2001), p. 168.

- ^ Dresden (1981), p. 9.

- ^ Brosius (2006), pp. 122–123.

- ^ An (2002), pp. 79–94.

- ^ Hansen (2012), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Scheidel (2009), p. 186.

- ^ Bagchi (2011), pp. 137–144.

- ^ Scheidel (2009), footnote #239 on p. 186.

- ^ Corbier (2005), p. 333.

- ^ Yule (1915), footnote #1 on p. 44.

- ^ Prowse, Tracy (2010). "Stable isotope and mtDNA evidence for geographic origins at the site of Vagnari, South Italy". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 78: 175–198.

- ^ University, McMaster (2010). "DNA testing on 2,000-year-old bones in Italy reveal East Asian ancestry". phys.org.

- ^ "Skeleton find could rewrite Roman history". BBC News. 23 September 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ Redfern, Rebecca C.; Gröcke, Darren R.; Millard, Andrew R.; Ridgeway, Victoria; Johnson, Lucie; Hefner, Joseph T. (2016). "Going south of the river: A multidisciplinary analysis of ancestry, mobility and diet in a population from Roman Southwark, London" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 74: 11–22. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.07.016.

- ^ Kristina Killgrove. (23 September 2016). "Chinese Skeletons In Roman Britain? Not So Fast". Forbes. Accessed 25 September 2016.

- ^ Dubs (1941), pp. 322–330.

- ^ Hoh, Erling (May–June 1999). "Romans in China?". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "Romans in China stir up controversy". China Daily. Xinhua online. 24 August 2005. Archived from the original on June 24, 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ "They came, saw and settled". The Economist. 16 December 2004. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Gruber, Ethan (2006). "The Origins of Roman Li-Chien". Pre-print: 18–21. doi:10.5281/zenodo.258105.

- ^ a b "Hunt for Roman Legion Reaches China". China Daily. Xinhua. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b Squires, Nick (23 November 2010). "Chinese Villagers 'Descended from Roman Soldiers'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 June 2012.

- ^ a b R. Zhou; et al. (2007). "Testing the Hypothesis of an Ancient Roman Soldier Origin of the Liqian People in Northwest China: a Y-Chromosome Perspective". Journal of Human Genetics. 52 (7): 584–91. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0155-0. PMID 17579807.

Sources

- Abraham, Curtis. (11 March 2015). "China’s long history in Africa". New African. Accessed 2 August 2017.

- Adshead, S. A. M. (1995) [1988]. China in World History, 2nd edition. New York: Palgrave MacMillan and St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-333-62132-5.

- An, Jiayao. (2002). "When Glass Was Treasured in China", in Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (eds), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, 79–94. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Bagchi, Prabodh Chandra (2011). Bangwei Wang and Tansen Sen (eds), India and China: Interactions Through Buddhism and Diplomacy: a Collection of Essays by Professor Prabodh Chandra Bagchi. London: Anthem Press. ISBN 93-80601-17-4.

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: Transformation of an Empire, 2nd edition. London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-72078-6.

- Bang, Peter F. (2009). "Commanding and Consuming the World: Empire, Tribute, and Trade in Roman and Chinese History", in Walter Scheidel (ed), Rome and China: Comparative Perspectives on Ancient World Empires, pp. 100–120. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-975835-7.

- Bai, Shouyi (2003), A History of Chinese Muslim, vol. 2, Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju, ISBN 978-7-101-02890-4.

- Bauman, Richard A. (2005). Crime and Punishment in Ancient Rome. London: Routledge, reprint of 1996 edition. ISBN 0-203-42858-7.

- Braun, Joachim (2002). Douglas W. Scott (trans), Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine: Archaeological, Written, and Comparative Sources. Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8028-4477-4.

- Bretschneider, Emil (1888). Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century, Vol. 1. Abingdon: Routledge, reprinted 2000.

- Brosius, Maria (2006). The Persians: An Introduction. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32089-5.

- Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2012). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China (240 BC – 1398 AD)", in Victor H. Mair (ed), Sino-Platonic Papers, No. 230. Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, University of Pennsylvania Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. ISSN 2157-9687.

- Corbier, Mireille. (2005). "Coinage and Taxation: the State's point of view, A.D. 193–337", in Alan K. Bowman, Peter Garnsey, and Averil Cameron (eds), The Cambridge Ancient History XII: the Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193–337, Vol. 12 (2nd edition), pp. 327–392. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-30199-8.

- Cumont, Franz (1933). The Excavations of Dura-Europos: Preliminary Reports of the Seventh and Eighth Seasons of Work. New Haven: Crai.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (2007). A Biographical Dictionary of Later Han to the Three Kingdoms (23–220 AD). Leiden: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15605-0.

- Dresden, Mark J. (1981). "Introductory Note", in Guitty Azarpay (ed.), Sogdian Painting: the Pictorial Epic in Oriental Art. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-03765-0.

- Dubs, Homer H. "An Ancient Military Contact between Romans and Chinese", in The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 62, No. 3 (1941), pp. 322–330.

- Encyclopædia Britannica. (1903) [1890]. Day Otis Kellogg (ed.), The New Americanized Encyclopædia Britannica: a General Encyclopædia of Art, Science, Literature, History, Biography, Invention, and Discovery, Covering the Whole Range of Human Knowledge, Vol. 3. Chicago: Saalfield Publishing (Riverside Publishing).

- Fan, Ye (September 2003). Hill, John E. (ed.). "The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu: The Xiyu juan, "Chapter on the Western Regions", from Hou Hanshu 88, Second Edition (Extensively revised with additional notes and appendices)". Depts.washington.edu. Translated by John E. Hill. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- Fontana, Michela (2011). Matteo Ricci: a Jesuit in the Ming Court. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-0586-4.

- Grant, R.G. (2005). Battle: A Visual Journey Through 5,000 Years of Combat. DK Pub. ISBN 978-0-7566-1360-0.

- Hansen, Valerie (2012). The Silk Road: A New History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-993921-3.

- Harper, P. O. (2002). "Iranian Luxury Vessels in China From the Late First Millennium B.C.E. to the Second Half of the First Millennium C.E.", in Annette L. Juliano and Judith A. Lerner (eds), Silk Road Studies VII: Nomads, Traders, and Holy Men Along China's Silk Road, 95–113. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers. ISBN 2-503-52178-9.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo's China: a Venetian in the Realm of Kublai Khan. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-34850-1.

- Hill, John E. (2009). Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, First to Second Centuries CE. BookSurge. ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hirth, Friedrich (2000) [1885]. Jerome S. Arkenberg (ed.). "East Asian History Sourcebook: Chinese Accounts of Rome, Byzantium and the Middle East, c. 91 B.C.E. – 1643 C.E." Fordham.edu. Fordham University. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Hirth, Friedrich (1885): China and the Roman Orient. 1875. Shanghai and Hong Kong. Unchanged reprint. Chicago: Ares Publishers, 1975.

- Hoh, Erling (May–June 1999). "Romans in China?". Archaeology.org. Archaeological Institute of America. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- Howard, Michael C. (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: the Role of Cross Border Trade and Travel. McFarland and Company.

- Jacobi, David (1999), "The Latin empire of Constantinople and the Frankish states in Greece", in David Abulafia (ed), The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 525–542. ISBN 0-521-36289-X.

- Kumar, Yukteshwar. (2005). A History of Sino-Indian Relations, 1st Century A.D. to 7th Century A.D.: Movement of Peoples and Ideas between India and China from Kasyapa Matanga to Yi Jing. New Delhi: APH Publishing. ISBN 81-7648-798-8.