Genetic history of Italy

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (October 2011) |

The genetic history of current Italians is greatly influenced by geography and history. The ancestors of Italians are both Indo-Europeans speakers (mainly Italics, followed by Greeks, Celts, Germanics,..) and pre-Indo-European ones (Etruscans, Rhaetians, etc.).

It is generally agreed that the invasions that followed for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire did not significantly alter the local gene pool, because of the relatively small number of Germanics, or other migrants, compared to the large population of what constituted Roman Italy.[2][3] Molecular anthropology found no evidence of significant Northern European geneflow into the Italian peninsula over the last 1500 years; DNA studies show that only the Greek colonization of Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) had a lasting effect on the local genetic landscape, and also find evidence of deep regional genetic substructure within Italy dating to the Roman and pre-Roman periods.[4][5][6][7]

Multiple DNA studies confirmed that genetic variation in Italy is clinal, going from the Eastern to the Western Mediterranean (with the Sardinians as outliers in Italy and Europe,[8] reflecting the Pre-Indo-European and non-Italic Nuragic ancestry) and that all Italians are made up of the same ancestral components, but in different proportions, related to the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age settlements of Europe.[9][10][11]

A study on some linguistic and isolated communities residing in Italy revealed that their genetic diversity is greater than that observed throughout the entire European continent at short (0–200 Km) and intermediate distances (700–800 Km), and account for most of the highest values of genetic distances observed at all geographic ranges.[12]

In their admixture ratios, the Italians are similar to other Southern Europeans, and that is being of Early Neolithic Farmer ancestry, with the Southern Italians being closest to the Greeks (as the historical region of Magna Graecia, "Great Greece", bears witness to)[13] and the Northern Italians being closest to the Spaniards and southern French;[14][10][15][16][17] the genetic gap between the northern and southern Italians is filled by an intermediate Central Italian cluster, creating a continuous cline of variation that mirrors geography.[18] The genetic distance between the Northern and the Southern Italians, although pretty large for a single European nationality, is only roughly equal to the one between the Northern and the Southern Germans.[19] Indeed, Northern and Southern Italians began to diverge as early as the Late Glacial and thus appear to encapsulate at a micro-geographic scale the cline of genetic diversity observable across Europe.[20]

The only exceptions are some alloglot populations (mostly Germanic and Slavic minorities from the region of Friuli-Venezia Giulia) who cluster with the Germanic- and Slavic-speaking Central Europeans from Austria and Slovenia,[21] as well as the Sardinians, who appear to be clearly differentiated from the populations of both Mainland Italy and Sicily.[22]

Historical populations of Italy

Modern man appeared during the Upper Paleolithic. Specimens of Aurignacian age were discovered in the cave of Fumane and dated back about 34,000 years ago. During the Magdalenian period the first men from the Pyrenees populated Sardinia.[23]

During the Neolithic farming was introduced by people from the east and the first villages were built, weapons became more sophisticated and the first objects in clay were produced. In the late Neolithic era the use of copper spread and villages were built over piles near lakes. In Sardinia, Sicily and part of Mainland Italy the Beaker culture spread from Western Europe.

During the Late Bronze Age the Urnfield Proto-Villanovan culture appeared in Central and Northern Italy, characterized by the typical rite of cremation of dead bodies originating from Central Europe, and the use of iron spread.[24] In Sardinia, the Nuragic civilization flourished.

At the dawn of the Iron Age much of Italy was inhabited by Italic tribes such as the Latins, Sabines, Samnites, Umbrians and Veneti; the northwest and alpine territories were populated primarily by non-Indo European tribes like the Ligurians and Raetians; while Iapygian tribes, possibly of Illyrian origin, populated Apulia.

From the 8th century BC, Greek colonists settled on the southern Italian coast and founded cities, initiating what would be later called Magna Graecia. During the same period Etruscan civilization developed on the coast of Southern Tuscany and Northern Latium. In the 5th century BC Gauls settled in Northern Italy and parts of Central Italy.[25] With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, different populations of German origin invaded Italy, the most significant being the Lombards[26], followed five centuries later by the Normans in Sicily.

Y-DNA genetic diversity

Many Italians, especially in Northern Italy and parts of Central Italy, belong to Haplogroup R1b, common in Western and Central Europe. The highest frequency of R1b is found in Garfagnana (76.2%) in Tuscany and in the Bergamo Valleys (80.8%) in Lombardy, Northern regions.[27][28] This percentage lowers at the south of Italy in Calabria (26.5%).[29] On the other hand, the majority of the Sardinians belong to Mesolithic European haplogroup I2a1a.[30]

A study from the Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore found that while Greek colonization left little significant genetic contribution, data analysis sampling 12 sites in the Italian peninsula supported a male demic diffusion model and Neolithic admixture with Mesolithic inhabitants.[31] The results supported a distribution of genetic variation along a north–south axis and supported demic diffusion. South Italian samples clustered with southeast and south-central European samples, and northern groups with West Europe.[32][33]

A 2004 study by Semino et al. showed that Italians from the north-central regions had around 26.9% J2; the Apulians, Calabrians and Sicilians had 31.4%, 24.6% and 23.8% J2 respectively; the Sardinians had 12.5% J2.[34]

A 2018 genetic study, focusing on the Y-chromosome and haplogroups lineages, their diversity and their distribution by taking some 817 representative subjects, gives credit to the traditional northern-southern division in population, by concluding that due to Neolithic migrations southern Italians "show a higher similarity with Middle Eastern and Southern Balkan populations than northern ones; conversely, northern samples are genetically closer to North-West Europe and Northern Balkan groups". The intermediate position of Volterra in central Tuscany is a mark of its unique Y-chromosomal genetic structure. It also keeps the debate about the origins of Etruscans open: the presence of J2a-M67* could substantiate the hypothesis of Herodotus, of a migration from the sea of a population related to the Anatolians; the presence of Central European lineage G2a-L497 at considerable frequency would rather support a Central European origin of the Etruscans; and finally, the high incidence of European R1b lineages—especially of haplogroup R1b-U152—could suggest an autochthonous origin due to a process of formation of the Etruscan civilisation from the preceding Villanovan culture, following the theories of Dionysius of Halicarnassus.[27]

Y-DNA introduced by historical immigration

Barbarian invasions that occurred on Italian soil following the fall of the Western Roman Empire have not significantly altered the gene pool of the Italian people.[2] These invasions generally consisted of relatively small groups of people that either did not remain on the peninsula or settled in densely populated areas of Italy, therefore becoming genetically diluted and assimilated into the predominant genetic population within a relatively short amount of time.[2] Despite the lengthy Goth and Lombard presence in Italy, the I1 haplogroup associated with the Norsemen is present only among 6–7% of mainland Italians,[35] peaking at 11% in the northeast (20% in Udine[36] and 30% in Stelvio[37]). An average frequency of 7% I1 has been detected in Sicily, 12% in the western part and 5% in the eastern.[38]

In two villages in Lazio and Abruzzo (Cappadocia and Vallepietra), I1 was recorded at levels 35% and 28%.[39] In Sicily, further migrations from the Vandals and Saracens have only slightly affected the ethnic composition of the Sicilian people. However, Greek genetic legacy is estimated at 37% in Sicily.[6]

The Norman Kingdom of Sicily was created in 1130, with Palermo as capital, 70 years after the initial Norman invasion and 40 after the conquest of the last town, Noto in 1091, and would last until 1198. Nowadays it is in north-west Sicily, around Palermo and Trapani, that Norman Y-DNA is the most common, with 15% to 20% of the lineages belonging to haplogroup I. The North African male contribution to Sicily was estimated between 3.5% and 7.5%.[40] Overall the estimated Central Balkan and North Western European paternal contributions in South Italy and Sicily are about 63% and 26% respectively.[41]

A 2015 genetic study of six small mountain villages in eastern Lazio and one mountain community in nearby western Abruzzo found some genetic similarities between these communities and Near Eastern populations, mainly in the male genetic pool. The Y haplogroup Q, common in Western Asia and Central Asia, was also found among this sample population, suggesting that in the past could have hosted a settlement from Central Asia.[42] But Q-M242 is distributed across most European countries at low frequencies, and the frequencies decrease to the west and to the south.

Genetic composition of Italians mtDNA

In Italy as elsewhere in Europe the majority of mtDNA lineages belong to the haplogroup H. Several independent studies conclude that haplogroup H probably evolved in West Asia c. 25,000 years ago. It was carried to Europe by migrations c. 20–25,000 years ago, and spread with population of the southwest of the continent.[43][44] Its arrival was roughly contemporary with the rise of the Gravettian culture. The spread of subclades H1, H3 and the sister haplogroup V reflect a second intra-European expansion from the Franco-Cantabrian region after the last glacial maximum, c. 13,000 years ago.[43][45]

African Haplogroup L lineages are relatively infrequent (less than 1%) throughout Italy with the exception of Latium, Volterra, Basilicata and Sicily where frequencies between 2 and 3% have been found.[46]

A study in 2012 by Brisighelli "et al." stated that an analysis of ancestral informative markers "as carried out in the present study indicated that Italy shows a very minor sub-Saharan African component that is, however, slightly higher than non-Mediterranean Europe." Discussing African mtDNAs the study states that these indicate that a significant proportion of these lineages could have arrived in Italy more than 10,000 years ago; therefore, their presence in Italy does not necessarily date to the time of the Roman Empire, the Atlantic slave trade or to modern migration."[11] These mtDNAs by Brisighelli "et al." were reported with the given results as "Mitochondrial DNA haplotypes of African origin are mainly represented by haplogroups M1 (0.3%), U6 (0.8%) and L (1.2%)" for the 583 samples tested.[11] The haplogroups M1 and U6 can be considered to be of North African origin and could therefore be used to signal the documented African historical input. Haplogroup M1 was observed in only two carriers from Trapani (West Sicily), while U6 was observed only in Lucera, South Apulia, and another at the tip of the Peninsula (Calabria).[11]

A 2013 study by Alessio Boattini et al. found 0 of African L haplogroup in the whole Italy out of 865 samples. The percentages for Berber M1 and U6 haplogroups were 0.46% and 0.35% respectively.[35]

A 2014 study by Stefania Sarno et al. found 0 of African L and M1 haplogroups in mainland Southern Italy out of 115 samples. Only two Berber U6 out of 115 samples were found, one from Lecce and one from Cosenza.[41]

Close genetic similarity between Ashkenazim and Italians has been noted in genetic studies, possibly due to the fact that Ashkenazi Jews have significant European admixture (30–60%), much of it Southern European, a lot of which came from Italy when diaspora males migrated to Rome and found wives among local women who then converted to Judaism.[47][48][49][50][51][15][52] More specifically, Ashkenazi Jews could be modeled as being 50% Levantine and 50% European, with an estimated mean South European admixure of 37.5%. Most of it (30.5%) seems to derive from an Italian source.[53][54]

A 2010 study of Jewish genealogy found that with respect to non-Jewish European groups, the population most closely related to Ashkenazi Jews are modern-day Italians followed by the French and Sardinians.[55][56]

Recent studies have shown that Italy has played an important role in the recovery of "Western Europe" at the end of the Last glacial period. The study focused mitochondrial U5b3 haplogroup discovered that this female lineage had in fact originated in Italy and that then expanded from the Peninsula around 10,000 years ago towards Provence and the Balkans. In Provence, probably between 9,000 and 7,000 years ago, it gave rise to the haplogroup subclade U5b3a1. This subclade U5b3a1 later came from Provence to the island of Sardinia by obsidian merchants, as it is estimated that 80% of obsidian found in France comes from Monte Arci in Sardinia reflecting the close relations that were at the time of these two regions. Still about 4% of the female population in Sardinia belongs to this haplotype.[57]

Autosomal

- In 2008, Dutch geneticists determined that Italy is one of the last two remaining genetic islands in Europe, the other being Finland. This is due in part to the presence of the Alpine mountain chain which, over the centuries, has prevented large migration flows aimed at colonizing the Italian lands.[58]

- Recent genome-wide studies have been able to detect and quantify admixture like never before. Li et al. (2008), using more than 600,000 autosomal SNPs, identify seven global population clusters, including European, Middle Eastern and Central/South Asian. All the Italian samples belong to Central-Western group with minor influences dating to Neolithic period.[59]

- López Herráez et al. (2009) typed the same samples at close to 1 million SNPs and analyzed them in a Western Eurasian context, identifying a number of subclusters. This time, all of the European samples show some minor admixture. Among the Italians, Tuscany still has the most, and Sardinia has a bit too, but so does Lombardy (Bergamo), which is even farther north.[60]

- A 2011 study by Moorjani et al. found that many southern Europeans have inherited 1–3% Sub-Saharan ancestry, although the percentages were lower (0.2–2.1%) when reanalyzed with the 'STRUCTURE' statistical model. An average admixture date of around 55 generations/1100 years ago was also calculated, "consistent with North African gene flow at the end of the Roman Empire and subsequent Arab migrations".[61]

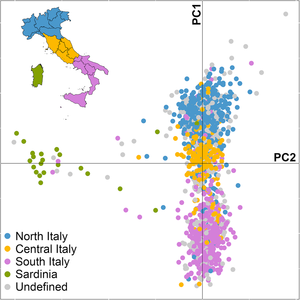

- A 2012 study by Di Gaetano et al. used 1,014 Italians with wide geographical coverage. It showed that the current population of Sardinia can be clearly differentiated genetically from mainland Italy and Sicily, and that a certain degree of genetic differentiation is detectable within the current Italian peninsula population.

By using the ADMIXTURE software, the authors obtained at K = 4 the lowest cross-validation error. The HapMap CEU individuals showed an average Northern Europe (NE) ancestry of 83%. A similar pattern is observed in French, Northern Italian and Central Italian populations with a NE ancestry of 70%, 56% and 52% respectively. According to the PCA plot, also in the ADMIXTURE analysis there are relatively small differences in ancestry between Northern Italians and Central Italians while Southern Italians showed a lower average admixture NE proportion (44%) than Northern and Central Italy, and a higher Middle East ancestry of 28%. The Sardinian samples display a pattern of crimson common to the others European populations but at a higher frequency (70%). The average admixture proportions for Northern European ancestry within current Sardinian population is 14.3% with some individuals exhibiting very low Northern European ancestry (less than 5% in 36 individuals on 268 accounting the 13% of the sample).[10]

- A 2013 study by Peristera Paschou et al. confirms that the Mediterranean Sea has acted as a strong barrier to gene flow through geographic isolation following initial settlements. Samples from (Northern) Italy, Tuscany, Sicily and Sardinia are closest to other Southern Europeans from Iberia, the Balkans and Greece, who are in turn closest to the Neolithic migrants that spread farming throughout Europe, represented here by the Cappadocian sample from Anatolia. But there hasn't been any significant admixture from the Middle East or North Africa into Italy and the rest of Southern Europe since then.[17]

- Ancient DNA analysis reveals that Ötzi the Iceman clusters with modern Southern Europeans and closest to Italians (the orange "Europe S" dots in the plots below), especially those from the island of Sardinia. Other Italians pull away toward Southeastern and Central Europe consistent with geography and some post-Neolithic gene flow from those areas (e.g. Italics, Greeks, Etruscans, Celts), but despite that and centuries of history, they're still very similar to their prehistoric ancestor.[62]

- A 2013 study by Botigué et al. 2013 applied an unsupervised clustering algorithm, ADMIXTURE, to estimate allele-based sharing between Africans and Europeans. Regarding Italians, the North African ancestry does not exceed 2% of their genomes. On average, 1% of Jewish ancestry is found in Tuscan HapMap population and Italian Swiss, as well as Greeks and Cypriots. Contrary to past observations, Sub-Saharan ancestry is detected at <1% in Europe, with the exception of the Canary Islands.[63]

- Haak et al. (2015) conducted a genome wide study of 94 ancient skeletons from Europe and Russia. The study argues that Bronze Age steppe pastoralists from the Yamna culture spread Indo-European languages in Europe. Autosomic tests indicate that the Yamnaya-people were the result of admixture between two different hunter-gatherer populations: Eastern Hunter-Gatherers from the Russian Steppe and either Caucasus Hunter-Gatherers or Chalcolithic Iranians (who are very similar). Wolfgang Haak estimated a 27% ancestral contribution of the Yamnaya in the DNA of modern Tuscans, a 25% ancestral contribution of the Yamnaya in the DNA of modern Northern Italians from Bergamo, excluding Sardinians (7%), and to a lesser extent Sicilians (12%).[14]

- A 2016 study Sazzini et al., confirms the results of previous studies by Di Gaetano et al. (2012) and Fiorito et al. (2015) but has much better geographical coverage of samples, with 737 individuals from 20 locations in 15 different regions being tested. The study also for the first time includes a formal admixture test that models the ancestry of Italians by inferring admixture events using all of the Western Eurasian samples. The results are very interesting in light of the ancient DNA evidence that has come out in the last couple years:

In addition to the pattern described in the main text, the SARD sample seemed to have played a major role as source of admixture for most of the examined populations, especially Italian ones, rather than as recipient of migratory processes. In fact, the most significant f3 scores for trios including SARD indicated peninsular Italians as plausible results of admixture between SARD and populations from Iran, Caucasus and Russia. This scenario could be interpreted as further evidence that Sardinians retain high proportions of a putative ancestral genomic background that was considerably widespread across Europe at least until the Neolithic and that has been subsequently erased or masked in most of present-day European populations.[18]

- A 2017 paper, concentrating on the genetic impact brought by the historical migrations around the Mediterranean on Southern Italy and Sicily, concludes that the "results demonstrate that the genetic variability of present-day Southern Italian populations is characterized by a shared genetic continuity, extending to large portions of central and eastern Mediterranean shores", while showing that "Southern Italy appear more similar to the Greek-speaking islands of the Mediterranean Sea, reaching as far east as Cyprus, than to samples from continental Greece, suggesting a possible ancestral link which might have survived in a less admixed form in the islands", also precises how "besides a predominant Neolithic-like component, our analyses reveal significant impacts of Post-Neolithic Caucasus- and Levantine-related ancestries."[4] A news article associated with the Max Planck Society, reviewing the results, while beginning by stating that "populations along the eastern Mediterranean coast share a genetic heritage that transcends nationality", also points out how this study is interesting on the debates concerning the diffusion of the Indo-European languages family in Europe, as, while showcasing the influence from the Caucasus, there's no genetic marker associated with the Pontic–Caspian steppe, "a very characteristic genetic signal well represented in North-Central and Eastern Europe, which previous studies associated with the introduction of Indo-European languages to the continent."[64]

See also

References

- ^ Parolo, Silvia; Lisa, Antonella; Gentilini, Davide; Di Blasio, Anna Maria; Barlera, Simona; Nicolis, Enrico B.; Boncoraglio, Giorgio B.; Parati, Eugenio A.; Bione, Silvia (2015). "Characterization of the biological processes shaping the genetic structure of the Italian population". BMC Genetics. 16: 132. doi:10.1186/s12863-015-0293-x. PMC 4640365. PMID 26553317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca; Menozzi, Paolo; Cavalli-Sforza, Luca; Piazza, Alberto; Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi (1994). The History and Geography of Human Genes. p. 295. ISBN 978-0691087504.

- ^ Antonio, M; Gao, Z; Lucci, M; et al. (2019). "Ancient Rome: A genetic crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean". Science. 366 (6466): 708–714. Bibcode:2019Sci...366..708A. doi:10.1126/science.aay6826. PMC 7093155. PMID 31699931.

- ^ a b Sarno, S; Boattini, A; Pagani, L; et al. (2017). "Ancient and recent admixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the Mediterranean". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 1984. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.1984S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01802-4. PMC 5434004. PMID 28512355.

- ^ Ralph, P; Coop, G (2013). "The geography of recent genetic ancestry across Europe". PLOS Biology. 11 (5): e1001555. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001555. PMC 3646727. PMID 23667324.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b "The genetic contribution of Greek chromosomes to the Sicilian gene pool is estimated to be about 37% whereas the contribution of North African populations is estimated to be around 6%.", Di Gaetano, C; Cerutti, N; Crobu, F; et al. (2009). "Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by genetic evidence from the Y chromosome". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (1): 91–99. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.120. PMC 2985948. PMID 18685561.

- ^ Raveane, A.; Aneli, S.; Montinaro, F.; Athanasiadis, G.; Barlera, S.; Birolo, G.; Boncoraglio, G. (4 September 2019). "Population structure of modern-day Italians reveals patterns of ancient and archaic ancestries in Southern Europe". Science Advances. 5 (9): eaaw3492. Bibcode:2019SciA....5.3492R. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw3492. PMC 6726452. PMID 31517044.

- ^ ..."La separazione della Sardegna dal resto del continente, anzi da tutte le altre popolazioni europee, che probabilmente rivela un'origine più antica della sua popolazione, indipendente da quella delle popolazioni italiche e con ascendenze nel Mediterraneo Medio-Orientale." Alberto Piazza, I profili genetici degli italiani, Accademia delle Scienze di Torino

- ^ Fiorito, G; Di Gaetano, C; Guarrera, S; Rosa, F; Feldman, MW; Piazza, A; Matullo, G (2016). "The Italian genome reflects the history of Europe and the Mediterranean basin". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (7): 1056–1062. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.233. PMC 5070887. PMID 26554880.

- ^ a b c Di Gaetano, C; Voglino, F; Guarrera, S; Fiorito, G; Rosa, F; Di Blasio, AM; Manzini, P; Dianzani, I; Betti, M; Cusi, D; Frau, F; Barlassina, C; Mirabelli, D; Magnani, C; Glorioso, N; Bonassi, S; Piazza, A; Matullo, G (2012). "An Overview of the Genetic Structure within the Italian Population from Genome-Wide Data". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e43759. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...743759D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043759. PMC 3440425. PMID 22984441.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d Brisighelli, F; Álvarez-Iglesias, V; Fondevila, M; Blanco-Verea, A; Carracedo, A; Pascali, VL; Capelli, C; Salas, A (2012). "Uniparental Markers of Contemporary Italian Population Reveals Details on Its Pre-Roman Heritage". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e50794. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750794B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050794. PMC 3519480. PMID 23251386.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Linguistic, geographic and genetic isolation: a collaborative study of Italian populations. M Capocasa et al., Journal of Anthropological Sciences, Vol 92(2014), pp. 201–231

- ^ «Sicily and Southern Italy were heavily colonized by Greeks beginning in the eight to ninth century B.C.. The demographic development of the Greek colonies in Southern Italy was remarkable, and in classical times this region was called Magna Graecia (Great Greece) because it probably surpassed in numbers the Greek population of the motherland.» Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Luca Cavalli-Sforza, Paolo Menozzi, Alberto Piazza. The History and Geography of Human Genes, Princeton University Press, 1994, p.278

- ^ a b Haak, W.; Lazaridis, I.; Patterson, N.; Rohland, N.; Mallick, S.; Llamas, B.; Brandt, G.; Nordenfelt, S.; Harney, E.; Stewardson, K.; Fu, Q.; Mittnik, A.; Bánffy, E.; Economou, C.; Francken, M.; Friederich, S.; Pena, R. G.; Hallgren, F.; Khartanovich, V.; Khokhlov, A.; Kunst, M.; Kuznetsov, P.; Meller, H.; Mochalov, O.; Moiseyev, V.; Nicklisch, N.; Pichler, S. L.; Risch, R.; Rojo Guerra, M. A.; et al. (2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–11. arXiv:1502.02783. Bibcode:2015Natur.522..207H. doi:10.1038/nature14317. PMC 5048219. PMID 25731166.

- ^ a b Tian, C; Kosoy, R; Nassir, R; et al. (2009). "European population genetic substructure: further definition of ancestry informative markers for distinguishing among diverse European ethnic groups". Mol. Med. 15 (11–12): 371–83. doi:10.2119/molmed.2009.00094. PMC 2730349. PMID 19707526.

- ^ Price, AL; Butler, J; Patterson, N; Capelli, C; Pascali, VL; Scarnicci, F; Ruiz-Linares, A; Groop, L; Saetta, AA; Korkolopoulou, P; Seligsohn, U; Waliszewska, A; Schirmer, C; Ardlie, K; Ramos, A; Nemesh, J; Arbeitman, L; Goldstein, DB; Reich, D; Hirschhorn, JN (2008). "Discerning the Ancestry of European Americans in Genetic Association Studies". PLOS Genetics. 4 (1): e236. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030236. PMC 2211542. PMID 18208327.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Peristera Paschou (2014). "Maritime route of colonization of Europe". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (25): 9211–16. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.9211P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320811111. PMC 4078858. PMID 24927591.

- ^ a b Sazzini, M.; Ruscone, G (2016). "Complex interplay between neutral and adaptive evolution shaped differential genomic background and disease susceptibility along the Italian peninsula". Nature. 6: 32513. Bibcode:2016NatSR...632513S. doi:10.1038/srep32513. PMC 5007512. PMID 27582244. Zendo: 165505.

- ^ Nelis, M; Esko, T; Mägi, R; et al. (2009). "Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East". PLOS ONE. 4 (5): e5472. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5472N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. PMC 2675054. PMID 19424496.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sazzini, Marco; Abondio, Paolo; Sarno, Stefania; Gnecchi-Ruscone, Guido Alberto; Ragno, Matteo; Giuliani, Cristina; De Fanti, Sara; Ojeda-Granados, Claudia; Boattini, Alessio; Marquis, Julien; Valsesia, Armand; Carayol, Jerome; Raymond, Frederic; Pirazzini, Chiara; Marasco, Elena; Ferrarini, Alberto; Xumerle, Luciano; Collino, Sebastiano; Mari, Daniela; Arosio, Beatrice; Monti, Daniela; Passarino, Giuseppe; d'Aquila, Patrizia; Pettener, Davide; Luiselli, Donata; Castellani, Gastone; Delledonne, Massimo; Descombes, Patrick; Franceschi, Claudio; Garagnani, Paolo (2020). "Genomic history of the Italian population recapitulates key evolutionary dynamics of both Continental and Southern Europeans". BMC Biology. 18 (1): 51. doi:10.1186/s12915-020-00778-4. PMC 7243322. PMID 32438927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Esko, T; Mezzavilla, M; Nelis, M; Borel, C; Debniak, T; Jakkula, E; Julia, A; Karachanak, S; Khrunin, A; Kisfali, P; Krulisova, V; Aušrelé Kučinskiené, Z; Rehnström, K; Traglia, M; Nikitina-Zake, L; Zimprich, F; Antonarakis, SE; Estivill, X; Glavač, D; Gut, I; Klovins, J; Krawczak, M; Kučinskas, V; Lathrop, M; Macek, M; Marsal, S; Meitinger, T; Melegh, B; Limborska, S; Lubinski, J; Paolotie, A; Schreiber, S; Toncheva, D; Toniolo, D; Wichmann, HE; Zimprich, A; Metspalu, M; Gasparini, P; Metspalu, A; D'Adamo, P (2013). "Genetic characterization of northeastern Italian population isolates in the context of broader European genetic diversity". European Journal of Human Genetics. 21 (6): 659–665. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.229. PMC 3658181. PMID 23249956.

- ^ Di Gaetano, Cornelia; Voglino, Floriana; Guarrera, Simonetta; Fiorito, Giovanni; Rosa, Fabio; Di Blasio, Anna Maria; Manzini, Paola; Dianzani, Irma; Betti, Marta; Cusi, Daniele; Frau, Francesca; Barlassina, Cristina; Mirabelli, Dario; Magnani, Corrado; Glorioso, Nicola; Bonassi, Stefano; Piazza, Alberto; Matullo, Giuseppe (2012). "An Overview of the Genetic Structure within the Italian Population from Genome-Wide Data". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e43759. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043759. PMC 3440425. PMID 22984441.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Siiri Rootsi: Y-Chromosome haplogroup I prehistoric gene flow in Europe Archived 2009-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, UDK 902(4)"631/634":577.2, Documenta Prehistorica XXXIII (2006)

- ^ [1] Culture del bronzo recente in Italia settentrionale e loro rapporti con la "cultura dei campi di urne" Archived May 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Haywood, John (2014). The Celts: Bronze Age to New Age. Routledge. p. 21. ISBN 978-1317870173.

- ^ "Lombard | people".

- ^ a b Grugni, V; Raveane, A; Mattioli, F; et al. (2018). "Reconstructing the genetic history of Italians: new insights from a male (Y-chromosome) perspective". Annals of Human Biology. 45 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1080/03014460.2017.1409801. PMID 29382284.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-20. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Tofanelli, S; Brisighelli, F; Anagnostou, P; Busby, GB; Ferri, G; Thomas, MG; Taglioli, L; Rudan, I; Zemunik, T; Hayward, C; Bolnick, D; Romano, V; Cali, F; Luiselli, D; Shepherd, GB; Tusa, S; Facella, A; Capelli, C (2016). "The Greeks in the West: genetic signatures of the Hellenic colonisation in southern Italy and Sicily". European Journal of Human Genetics. 24 (3): 429–36. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2015.124. PMC 4757772. PMID 26173964.

- ^ Francalacci P, et al. (July 2003). "Peopling of three Mediterranean islands (Corsica, Sardinia, and Sicily) inferred by Y-chromosome biallelic variability". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 121 (3): 270–79. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10265. PMID 12772214.

- ^ Capelli, C; Brisighelli, F; Scarnicci, F; et al. (July 2007). "Y chromosome genetic variation in the Italian peninsula is clinal and supports an admixture model for the Mesolithic-Neolithic encounter". Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44 (1): 228–39. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.11.030. PMID 17275346.

- ^ Capelli, C.; et al. (2007). "Y chromosome genetic variation in the Italian peninsula is clinal" (PDF). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44 (1): 228–39. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.11.030. PMID 17275346. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-28.

- ^ The History and Geography of Human Genes Search results for "Southern Italy" on Google Books

- ^ Semino, Ornella; et al. (2004). "Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area". American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1023–34. doi:10.1086/386295. PMC 1181965. PMID 15069642.

- ^ a b Boattini, A; Martinez-Cruz, B; Sarno, S; Harmant, C; Useli, A; Sanz, P; Yang-Yao, D; Manry, J; Ciani, G; Luiselli, D; Quintana-Murci, L; Comas, D; Pettener, D (2013). "Uniparental Markers in Italy Reveal a Sex-Biased Genetic Structure and Different Historical Strata". PLOS ONE. 8 (5): e65441. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...865441B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0065441. PMC 3666984. PMID 23734255.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Brisighelli, Francesca; Álvarez-Iglesias, Vanesa; Fondevila, Manuel; Blanco-Verea, Alejandro; Carracedo, Ángel; Pascali, Vincenzo L.; Capelli, Cristian; Salas, Antonio (2012). "Uniparental Markers of Contemporary Italian Population Reveals Details on its Pre-Roman Heritage". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e50794. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750794B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050794. PMC 3519480. PMID 23251386.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Pichler, Irene; Mueller, Jakob C.; Stefanov, Stefan A.; De Grandi, Alessandro; Volpato, Claudia BEU; Pinggera, Gerd K.; Mayr, Agnes; Ogriseg, Martin; Ploner, Franz; Meitinger, Thomas; Pramstaller, Peter P. (2006). "Genetic Structure in Contemporary South Tyrolean Isolated Populations Revealed by Analysis of Y-Chromosome, mtDNA, and Alu Polymorphisms". Human Biology. 78 (4): 441–64. doi:10.1353/hub.2006.0057. JSTOR 41466425. PMID 17278620.

- ^ "European Journal of Human Genetics – Table 1 for article: Differential Greek and northern African migrations to Sicily are supported by genetic evidence from the Y chromosome". Nature. 17.

- ^ Messina, Francesco; Finocchio, Andrea; Rolfo, Mario Federico; De Angelis, Flavio; Rapone, Cesare; Coletta, Martina; Martínez-Labarga, Cristina; Biondi, Gianfranco; Berti, Andrea; Rickards, Olga (2015). "Traces of forgotten historical events in mountain communities in Central Italy: A genetic insight". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (4): 508–19. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22677. PMID 25728801.

- ^ Capelli, C; Onofri, V; Brisighelli, F; et al. (2009). "Moors and Saracens in Europe, estimating the medieval North African male legacy in southern Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 848–52. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.258. PMC 2947089. PMID 19156170.

- ^ a b Sarno, S; Boattini, A; Carta, M; Ferri, G; Alù, M; Yao, DY; Ciani, G; Pettener, D; Luiselli, D (2014). "An Ancient Mediterranean Melting Pot: Investigating the Uniparental Genetic Structure and Population History of Sicily and Southern Italy". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e96074. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996074S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096074. PMC 4005757. PMID 24788788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Messina, F; Finocchio, A; Rolfo, MF; De Angelis, F; Rapone, C; Coletta, M; Martínez-Labarga, C; Biondi, G; Berti, A; Rickards, O (2015). "Traces of forgotten historical events in mountain communities in Central Italy: A genetic insight". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (4): 508–19. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22677. PMID 25728801.

- ^ a b Pereira L, Richards M, Goios A, et al. (January 2005). "High-resolution mtDNA evidence for the late-glacial resettlement of Europe from an Iberian refugium". Genome Research. 15 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1101/gr.3182305. PMC 540273. PMID 15632086.

- ^ Richards M, Macaulay V, Hickey E, et al. (November 2000). "Tracing European Founder Lineages in the Near Eastern mtDNA Pool". American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (5): 1251–76. doi:10.1016/S0002-9297(07)62954-1. PMC 1288566. PMID 11032788.

- ^ Achilli A, Rengo C, Magri C, et al. (November 2004). "The Molecular Dissection of mtDNA Haplogroup H Confirms That the Franco-Cantabrian Glacial Refuge Was a Major Source for the European Gene Pool". American Journal of Human Genetics. 75 (5): 910–18. doi:10.1086/425590. PMC 1182122. PMID 15382008.

- ^ 4/138=2.9% in Latium; 3/114=2.6% in Volterra; 2/92=2.2% in Basilicata and 3/154=2.0% in Sicily, Achilli, A; Olivieri, A; Pala, M; et al. (April 2007). "Mitochondrial DNA variation of modern Tuscans supports the near eastern origin of Etruscans". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 80 (4): 759–68. doi:10.1086/512822. PMC 1852723. PMID 17357081.

- ^ "Tracing the Roots of Jewishness". 2010-06-03.

- ^ Zoossmann-Diskin, Avshalom (2010). "The origin of Eastern European Jews revealed by autosomal, sex chromosomal and mtDNA polymorphisms". Biol Direct. 5 (57): 57. doi:10.1186/1745-6150-5-57. PMC 2964539. PMID 20925954.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Did Modern Jews Originate in Italy? Michael Balter, ScienceNOW, 8 October 2013

- ^ Genetic Roots of the Ashkenazi Jews

- ^ Rosenberg NA, et al. (December 2002). "Genetic structure of human populations". Science. 298 (5602): 2381–85. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.2381R. doi:10.1126/science.1078311. PMID 12493913. S2CID 8127224.

- ^ M. D. Costa and 16 others (2013). "A substantial prehistoric European ancestry amongst Ashkenazi maternal lineages". Nature Communications. 4: 2543. Bibcode:2013NatCo...4.2543C. doi:10.1038/ncomms3543. PMC 3806353. PMID 24104924.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Banda et al. "Admixture Estimation in a Founder Population". Am Soc Hum Genet, 2013".

- ^ Bray, SM; Mulle, JG; Dodd, AF; Pulver, AE; Wooding, S; Warren, ST (September 2010). "Signatures of founder effects, admixture, and selection in the Ashkenazi Jewish population". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (37): 16222–27. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10716222B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1004381107. PMC 2941333. PMID 20798349.

- ^ Atzmon, Gil; Hao, Li; Pe'Er, Itsik; Velez, Christopher; Pearlman, Alexander; Palamara, Pier Francesco; Morrow, Bernice; Friedman, Eitan; Oddoux, Carole; Burns, Edward; Ostrer, Harry (2010). "Abraham's Children in the Genome Era: Major Jewish Diaspora Populations Comprise Distinct Genetic Clusters with Shared Middle Eastern Ancestry". American Journal of Human Genetics. 86 (6): 850–59. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.015. PMC 3032072. PMID 20560205.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Genes Set Jews Apart, Study Finds". American Scientist. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ [2] American Journal of Human Genetics : Mitochondrial Haplogroup U5b3: A Distant Echo of the Epipaleolithic in Italy and the Legacy of the Early Sardinians

- ^ "Genetic Map of Europe". New York Times. August 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-27. Retrieved 2015-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ López Herráez, D; Bauchet, M; Tang, K; et al. (2009). "Genetic Variation and Recent Positive Selection in Worldwide Human Populations: Evidence from Nearly 1 Million SNPs". PLOS ONE. 4 (11): e7888. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7888L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007888. PMC 2775638. PMID 19924308.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Moorjani P, Patterson N, Hirschhorn JN, Keinan A, Hao L, Atzmon G, Burns E, Ostrer H, Price AL, Reich D (April 2011). McVean G (ed.). "The history of African gene flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews". PLoS Genetics. 7 (4): e1001373. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001373. PMC 3080861. PMID 21533020.

- ^ Keller, A; Graefen, A; Ball, M; et al. (2012). "New insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's origin and phenotype as inferred by whole-genome sequencing". Nature Communications. 3: 698. Bibcode:2012NatCo...3..698K. doi:10.1038/ncomms1701. PMID 22426219.

- ^ Sarno, Stefania; Boattini, Alessio; Carta, Marilisa; Ferri, Gianmarco; Alù, Milena; Yao, Daniele Yang; Ciani, Graziella; Pettener, Davide; Luiselli, Donata (2014). "An Ancient Mediterranean Melting Pot: Investigating the Uniparental Genetic Structure and Population History of Sicily and Southern Italy". PLOS ONE. 9 (4): e96074. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...996074S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0096074. PMC 4005757. PMID 24788788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

This article contains quotations from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- ^ Max Planck Society, Populations along the eastern Mediterranean coast share a genetic heritage that transcends nationality, Phys.Org, May 17, 2017