Second Opium War

| Second Opium War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Opium Wars | |||||||||

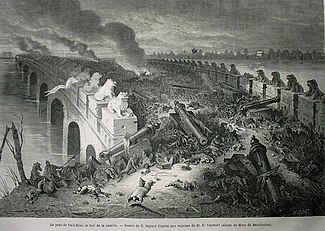

Palikao's bridge, on the evening of the battle, by Émile Bayard | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

British: 13,127[1] French: 7,000[2] |

200,000 (Eight Banners and Green Standard Army) | ||||||||

| 1 The U.S. was officially neutral, but later aided the British in the Battle of the Barrier Forts (1856) and the Battle of Taku Forts (1859).[3] | |||||||||

The Second Opium War (Chinese: 第二次鴉片戰爭; pinyin: Dì'èrcì Yāpiàn Zhànzhēng), also known as the Second Anglo-Chinese War, the Second China War, the Arrow War, or the Anglo-French expedition to China,[4] was a war pitting the British Empire and the French Empire against the Qing dynasty of China that lasted from 1856 to 1860.

It was the second major war in the Opium Wars, fought over issues relating to the exportation of opium to China, and resulted in a second defeat for the Qing dynasty. The agreements of the Convention of Peking led to the ceding of Kowloon Peninsula as part of Hong Kong.

Names

The terms "Second War" and "Arrow War" are both used in literature. "Second Opium War" refers to one of the British strategic objectives: legalizing the opium trade, expanding trade, opening all of China to British merchants, and exempting foreign imports from internal transit duties.[citation needed] The "Arrow War" refers to the name of a vessel which became the starting point of the conflict.

Origins of the war

The war followed on from the First Opium War. In 1842, the Treaty of Nanjing—the first of what the Chinese later called the unequal treaties—granted an indemnity and extraterritoriality to Britain, the opening of five treaty ports, and the cession of Hong Kong Island. The failure of the treaty to satisfy British goals of improved trade and diplomatic relations led to the Second Opium War (1856–60).[5] In China, the First Opium War is considered to have been the beginning of modern Chinese history.

Between the two wars, repeated acts of aggression against British subjects led in 1847 to the Expedition to Canton which assaulted and took, by a coup de main, the forts of the Bocca Tigris resulting in the spiking of 879 guns.[6]: 501

Outbreak

The 1850s saw the rapid growth of Western imperialism. Some of the shared goals of the western powers were the expansion of their overseas markets and the establishment of new ports of call. The French Treaty of Huangpu and the American Wangxia Treaty both contained clauses allowing renegotiation of the treaties after 12 years of being in effect. In an effort to expand their privileges in China, Britain demanded the Qing authorities renegotiate the Treaty of Nanjing (signed in 1842), citing their most favoured nation status. The British demands included opening all of China to British merchant companies, legalising the opium trade, exempting foreign imports from internal transit duties, suppression of piracy, regulation of the coolie trade, permission for a British ambassador to reside in Beijing and for the English-language version of all treaties to take precedence over the Chinese language.[7]

To give Chinese merchant vessels operating around treaty ports the same privileges accorded to British ships by the Treaty of Nanjing, British authorities granted these vessels British registration in Hong Kong. In October 1856, Chinese marines in Canton seized a cargo ship called the Arrow on suspicion of piracy, arresting twelve of its fourteen Chinese crew members. The Arrow had previously been used by pirates, captured by the Chinese government, and subsequently resold. It was then registered as a British ship and still flew the British flag at the time of its detainment, though its registration had expired. Its captain, Thomas Kennedy, who was aboard a nearby vessel at the time, reported seeing Chinese marines pull the British flag down from the ship.[8] The British consul in Canton, Harry Parkes, contacted Ye Mingchen, imperial commissioner and Viceroy of Liangguang, to demand the immediate release of the crew, and an apology for the alleged insult to the flag. Ye released nine of the crew members, but refused to release the last three.[citation needed]

On 23 October the British destroyed four barrier forts.[9] On 25 October a demand was made for the British to be allowed to enter the city. The next day, the British started to bombard the city, firing one shot every 10 minutes.[9] Ye Mingchen issued a bounty on every British head taken.[9] On 29 October a hole was blasted in the city walls and troops entered, with a flag of the United States being planted by James Keenan (U.S. Consul) on the walls and residence of Ye Mingchen.[9] Losses were 3 killed and 12 wounded. Negotiations failed and the city was bombarded. On 6 November 23 war junks attacked and were destroyed.[10] There were pauses for talks, with the British bombarding at intervals, fires were caused, then on 5 January 1857, the British returned to Hong Kong.[9]

British delays

The British government lost a Parliamentary vote regarding the Arrow incident and what had taken place at Canton to the end of the year on 3 March 1857. Then there was a general election in April 1857 which increased the government majority.[citation needed]

In April, the British government asked the United States of America and Russia if they were interested in alliances, but both parties rejected the offer.[9] In May 1857, the Indian Mutiny became serious. British troops destined for China were diverted to India,[6] which was considered the priority issue.[citation needed]

Intervention of France

France joined the British action against China, prompted by complaints from their envoy, Baron Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros, over the execution of a French missionary, Father Auguste Chapdelaine,[11] by Chinese local authorities in Guangxi province, which at that time was not open to foreigners.[12]

The British and the French joined forces under Admiral Sir Michael Seymour. The British army, which was led by Lord Elgin, and the French army, which was led by Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros, jointly attacked and occupied Canton (now known as Guangzhou) in late 1857. A joint committee of the Alliance was formed. The Allies left the city governor at his original post in order to maintain order on behalf of the victors. The British-French alliance maintained control of Canton for nearly four years.[citation needed]

The coalition then cruised north to briefly capture the Taku Forts near Tientsin (now known as Tianjin) in May 1858.[citation needed]

Intervention by other states

The United States and Russia sent envoys to Hong Kong to offer military help to the British and French, though in the end Russia sent no military aid.[7]

The U.S. was involved in a minor concurrent conflict during the war, although they ignored the UK's offer of alliance and did not coordinate with the Anglo-French forces. In 1856, the Chinese garrison at Canton shelled a United States Navy steamer;[10] the U.S. Navy retaliated in the Battle of the Pearl River Forts. The ships bombarded then attacked the river forts near Canton, taking them. Diplomatic efforts were renewed afterward, and the American and Chinese governments signed an agreement for U.S. neutrality in the Second Opium War.[citation needed]

Despite the U.S. government's promise of neutrality, the USS San Jacinto aided the Anglo-French alliance in the bombardment of the Taku Forts in 1859.

Battle of Canton

Through 1857, British forces began to assemble in Hong Kong, joined by a French force. In December 1857 they had sufficient ships and men to raise the issue of the non-fulfilment of the treaty obligations by which the right of entry into Canton had been accorded.[6]: 502 Parkes delivered an ultimatum, supported by Hong Kong governor Sir John Bowring and Admiral Sir Michael Seymour, threatening on 14 December to bombard Canton if the men were not released within 24 hours.[9] [13]

The remaining crew of the Arrow were then released, with no apology from Viceroy Ye Mingchen who also refused to honour the treaty terms. Seymour, Major General van Straubenzee and Admiral de Genouilly agreed the plan to attack Canton as ordered.[6]: 503 This event came to be known as the Arrow Incident and provided the alternative name of the ensuing conflict.[14]

The capture of Canton, on 1 January 1858,[9] a city with a population of over 1,000,000[15] by less than 6,000 troops, resulted in the British and French forces suffering 15 killed and 113 wounded. 200–650 of the defenders and inhabitants became casualties.[citation needed] Ye Mingchen was captured and exiled to Calcutta, India, where he starved himself to death.[16]

British attacks

Although the British were delayed by the Indian Rebellion of 1857, they followed up the Arrow Incident in 1856 and attacked Guangzhou from the Pearl River. Viceroy Ye Mingchen ordered all Chinese soldiers manning the forts not to resist the British incursion. After taking the fort near Guangzhou with little effort, the British Army attacked Guangzhou.[citation needed]

Meanwhile, in Hong Kong, there was a possible attempt to poison John Bowring and his family in January, known as the Esing Bakery incident. However, if it was deliberate, the baker who had been charged with lacing bread with arsenic bungled the attempt by putting an excess of the poison into the dough, such that his victims vomited sufficient quantities of the poison that they had only a non-lethal dose left in their system. Criers were sent out with an alert, preventing further injury.[17]

When known in Britain, the Arrow incident (and the British military response) became the subject of controversy. The British House of Commons on 3 March passed a resolution by 263 to 249 against the Government saying:

That this House has heard with concern of the conflicts which have occurred between the British and Chinese authorities on the Canton River; and, without expressing an opinion as to the extent to which the Government of China may have afforded this country cause of complaint respecting the non-fulfilment of the Treaty of 1842, this House considers that the papers which have been laid on the table fail to establish satisfactory grounds for the violent measures resorted to at Canton in the late affair of the Arrow, and that a Select Committee be appointed to inquire into the state of our commercial relations with China.[18]

In response, Lord Palmerston attacked the patriotism of the Whigs who sponsored the resolution and Parliament was dissolved, causing the British general election of March 1857.[citation needed]

The Chinese issue figured prominently in the election, and Palmerston won with an increased majority, silencing the voices within the Whig faction who supported China. The new parliament decided to seek redress from China based on the report about the Arrow Incident submitted by Harry Parkes. The French Empire, the United States, and the Russian Empire received requests from Britain to form an alliance.[citation needed]

Interlude

Treaties of Tianjin

In June 1858, the first part of the war ended with the four Treaties of Tientsin, to which Britain, France, Russia, and the U.S. were parties. These treaties opened 11 more ports to Western trade. The Chinese initially refused to ratify the treaties.

The major points of the treaty were:

- Britain, France, Russia, and the U.S. would have the right to establish diplomatic legations (small embassies) in Peking (a closed city at the time)

- Ten more Chinese ports would be opened for foreign trade, including Niuzhuang, Tamsui, Hankou, and Nanjing

- The right of all foreign vessels including commercial ships to navigate freely on the Yangtze River

- The right of foreigners to travel in the internal regions of China, which had been formerly banned

- China was to pay an indemnity of four million taels of silver to Britain and two million to France.[19]

Treaty of Aigun

On 28 May 1858, the separate Treaty of Aigun was signed with Russia to revise the Chinese and Russian border as determined by the Nerchinsk Treaty in 1689. Russia gained the left bank of the Amur River, pushing the border south from the Stanovoy mountains. A later treaty, the Convention of Peking in 1860, gave Russia control over a non-freezing area on the Pacific coast, where Russia founded the city of Vladivostok in 1860.

Second phase

Three battles of Taku Forts

On 20 May, the British were successful at the First Battle of Taku Forts, but the peace treaty returned the forts to the Qing army.

In June 1858, shortly after the Qing imperial court agreed to the disadvantageous treaties, hawkish ministers prevailed upon the Xianfeng Emperor to resist Western encroachment. On 2 June 1858, the Xianfeng Emperor ordered the Mongol general Sengge Rinchen to guard the Taku Forts (also romanized as Ta-ku Forts and also called Daku Forts) near Tianjin. Sengge Rinchen reinforced the forts with additional artillery pieces. He also brought 4,000 Mongol cavalry from Chahar and Suiyuan.

The Second Battle of Taku Forts took place in June 1859. A British naval force with 2,200 troops and 21 ships, under the command of Admiral Sir James Hope, sailed north from Shanghai to Tianjin with newly appointed Anglo-French envoys for the embassies in Beijing. They sailed to the mouth of the Hai River guarded by the Taku Forts near Tianjin and demanded to continue inland to Beijing. Sengge Rinchen replied that the Anglo-French envoys might land up the coast at Beitang and proceed to Beijing but he refused to allow armed troops to accompany them to the Chinese capital. The Anglo-French forces insisted on landing at Taku instead of Beitang and escorting the diplomats to Beijing. On the night of 24 June 1859, a small group of British forces blew up the iron obstacles that the Chinese had placed in the Baihe River. The next day, the British forces sought to forcibly sail into the river, and shelled the Taku Forts. Low tide and soft mud prevented their landing, however, and accurate fire from Sengge Rinchen's cannons sank four gunboats and severely damaged two others. American Commodore Josiah Tattnall, although under orders to maintain neutrality, declared "blood is thicker than water," and provided covering fire to protect the British convoy's retreat. The failure to take the Taku Forts was a blow to British prestige, and anti-foreign resistance reached a crescendo within the Qing imperial court.[20]

Once the Indian Mutiny was finally quelled, Sir Colin Campbell, commander-in-chief in India, was free to amass troops and supplies for another offensive in China. A 'soldiers' general', Campbell's experience of casualties from disease in the First Opium War led him to provide the British forces with more than enough materiel and supplies, and casualties were light.[21]

The Third Battle of Taku Forts took place in the summer of 1860. London once more dispatched Lord Elgin with an Anglo-French force of 11,000 British troops under General James Hope Grant and 6,700 French troops under General Cousin-Montauban. They pushed north with 173 ships from Hong Kong and captured the port cities of Yantai and Dalian to seal the Bohai Gulf. On 3 August they carried out a landing near Beitang (also romanized as "Pei-t'ang"), some 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from the Taku Forts, which they captured after three weeks on 21 August.

Southern Chinese laborers served with the French and British forces. One observer reported that the "Chinese coolies", as he called them, "renegades though they were, served the British faithfully and cheerfully... At the assault of the Peiho Forts in 1860 they carried the French ladders to the ditch, and, standing in the water up to their necks, supported them with their hands to enable the storming party to cross. It was not usual to take them into action; they, however, bore the dangers of a distant fire with great composure, evincing a strong desire to close with their compatriots, and engage them in mortal combat with their bamboos."[22]

Diplomatic incident

After taking Tianjin on 23 August, the Anglo-French forces marched inland toward Beijing. The Xianfeng Emperor then dispatched ministers for peace talks, but the British diplomatic envoy, Harry Parkes, insulted the imperial emissary and word arrived that the British had kidnapped the prefect of Tianjin. Parkes was arrested in retaliation on 18 September.[23] Parkes and his entourage were imprisoned and interrogated. Half were reportedly executed by slow slicing, with the application of tourniquets to severed limbs to prolong the torture. This infuriated British leadership when they recovered the unrecognizable bodies.[citation needed]

Burning of the Summer Palaces

The Anglo-French forces clashed with Sengge Rinchen's Mongol cavalry on 18 September at the battle of Zhangjiawan before proceeding toward the outskirts of Beijing for a decisive battle in Tongzhou (also romanized as Tungchow).[24] On 21 September, at Baliqiao (Eight Mile Bridge), Sengge Rinchen's 10,000 troops, including the elite Mongol cavalry, were annihilated after doomed frontal charges against concentrated firepower of the Anglo-French forces, which entered Beijing on 6 October.

With the Qing army devastated, the Xianfeng Emperor fled the capital and left behind his brother, Prince Gong, to take charge of peace negotiations. Xianfeng first fled to the Chengde Summer Palace and then to Rehe Province.[25] Anglo-French troops in Beijing began looting the Summer Palace (Yiheyuan) and Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) immediately (as they were full of valuable artwork).

After Parkes and the surviving diplomatic prisoners were freed on 8 October, Lord Elgin ordered the Summer Palaces to be destroyed, starting on 18 October. Beijing was not occupied; the Anglo-French army remained outside the city.

The destruction of the Forbidden City was discussed, as proposed by Lord Elgin to discourage the Qing Empire from using kidnapping as a bargaining tool, and to exact revenge on the mistreatment of their prisoners.[26] Elgin's decision was further motivated by the torture and murder of almost twenty Western prisoners, including two British envoys and a journalist for The Times.[27] The Russian envoy Count Ignatiev and the French diplomat Baron Gros settled on the burning of the Summer Palaces instead, since it was "least objectionable" and would not jeopardise the signing of the treaty.[26]

Awards

Both Britain (Second China War Medal) and France (Commemorative medal of the 1860 China Expedition) issued campaign medals. The British medal had the following clasps: China 1842, Fatshan 1857, Canton 1857, Taku Forts 1858, Taku Forts 1860, Peking 1860.

![]() 7 awards were made of the Victoria Cross, all for Gallantry shown on 21 August 1860 by soldiers of the 44th Regiment of Foot and the 67th Regiment of Foot at the Battle of Taku Forts (1860) (see List of Victoria Cross recipients by campaign)

7 awards were made of the Victoria Cross, all for Gallantry shown on 21 August 1860 by soldiers of the 44th Regiment of Foot and the 67th Regiment of Foot at the Battle of Taku Forts (1860) (see List of Victoria Cross recipients by campaign)

Battle honours

The following regiments fought in the campaign:

- British and Empire

- Cavalry Brigade

- 1st King's Dragoon Guards

- Probyn's Sikh Horse (5th Horse – Pakistan)

- Fane's Mahratta Cavalry (19th Lancers – Pakistan)

- Infantry

- 1st Regiment of Foot (Scots – 2nd Battalion)

- 2nd Regiment of Foot (Queen's)

- 3rd Regiment of Foot (Buffs)

- 8th Regiment of Punjab Infantry (Punjab Regiment – 6th Battalion – Pakistan)

- 15th Ludhiana Sikhs (Sikh Regiment – 2nd Battalion – India)

- 19th Punjaub Infantry (Punjab Regiment – 5th Battalion – Pakistan)

- 23rd Punjab Pioneers (Sikh Light Infantry – India)

- 31st Regiment of Foot (Huntingdonshire)

- 44th Regiment of Foot (East Essex)

- 60th Regiment of Foot (King's Royal Rifles)

- 67th Regiment of Foot (South Hampshire)

- 99th Regiment of Foot (Lanarkshire)

- Royal Marines

- Artillery

- Engineers

- Royal Engineers, no. 8 company

- Madras Sappers and Miners (Indian Army Corps of Engineers)

- Cavalry Brigade

- French

- Cavalry

- Infantry

- US

- Naval

Aftermath

After the Xianfeng Emperor and his entourage fled Beijing, the June 1858 Treaty of Tientsin was ratified by the emperor's brother, Prince Gong, in the Convention of Peking on 18 October 1860, bringing the Second Opium War to an end.

The British, French and—thanks to the schemes of Ignatiev—the Russians were all granted a permanent diplomatic presence in Beijing (something the Qing Empire resisted to the very end as it suggested equality between China and the European powers). The Chinese had to pay 8 million taels to Britain and France. Britain acquired Kowloon (next to Hong Kong). The opium trade was legalized and Christians were granted full civil rights, including the right to own property, and the right to evangelize.

The content of the Convention of Beijing included:

- China's signing of the Treaty of Tianjin

- Opening Tianjin as a trade port

- Cede No.1 District of Kowloon (south of present-day Boundary Street) to Britain

- Freedom of religion established in China

- British ships were allowed to carry indentured Chinese to the Americas

- Indemnity to Britain and France increasing to 8 million taels of silver apiece

- Legalization of the opium trade

Two weeks later, Ignatiev forced the Qing government to sign a "Supplementary Treaty of Peking", which ceded the Maritime Provinces east of the Ussuri River (forming part of Outer Manchuria) to the Russians, who went on to found the port of Vladivostok between 1860–61. The Anglo-French victory was heralded in the British press as a triumph for British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, which made his popularity rise to new heights. British merchants were delighted at the prospects of the expansion of trade in the Far East. Other foreign powers were pleased with the outcome too, since they hoped to take advantage of the opening-up of China.

The defeat of the Qing army by a relatively small Anglo-French military force (outnumbered at least 10 to 1 by the Qing army) coupled with the flight (and subsequent death) of the Xianfeng Emperor and the burning of the Summer Palaces was a shocking blow to the once powerful Qing Empire. "Beyond a doubt, by 1860 the ancient civilization that was China had been thoroughly defeated and humiliated by the West."[28] After the war, a major modernization movement, known as the Self-Strengthening Movement, began in China in the 1860s and several institutional reforms were initiated.

The opium trade incurred intense enmity from the later British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone.[29] As a member of Parliament, Gladstone called it "most infamous and atrocious", referring to the opium trade between China and British India in particular.[30] Gladstone was fiercely against both of the Opium Wars, was ardently opposed to the British trade in opium to China, and denounced British violence against Chinese.[31] Gladstone lambasted it as "Palmerston's Opium War" and said that he felt "in dread of the judgments of God upon England for our national iniquity towards China" in May 1840.[32] A famous speech was made by Gladstone in Parliament against the First Opium War.[33][34] Gladstone criticized it as "a war more unjust in its origin, a war more calculated in its progress to cover this country with permanent disgrace".[35] His hostility to opium stemmed from the effects of the drug upon his sister Helen.[36] Due to the First Opium war brought on by Palmerston, Gladstone was initially reluctant to join the government of Peel before 1841.[37]

See also

- China–United Kingdom relations

- Imperialism in Asia

- Nian Rebellion

- Miao Rebellion (1854–73)

- Dungan Revolt (1862–77)

- Panthay Rebellion

- History of Beijing

- Taiping Rebellion

References

Citations

- ^ Frontier and Overseas Expeditions from India. Volume 6. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing. 1911. p. 446.

- ^ Wolseley, G. J. (1862). Narrative of the War with China in 1860. London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts. p. 1.

- ^ Magoc, Chris J.; Bernstein, David (2016). Imperialism and Expansionism in American History. Volume 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 295. ISBN 9781610694308.

- ^ Michel Vié, Histoire du Japon des origines a Meiji, PUF, p. 99. ISBN 2-13-052893-7.

- ^ Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841–1997. I.B. Tauris. p. 29. ISBN 9781845114190.

- ^ a b c d Porter, Maj Gen Whitworth (1889). History of the Corps of Royal Engineers Vol I. Chatham: The Institution of Royal Engineers.

- ^ a b "Opium Wars". www.mtholyoke.edu. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Hanes & Sanello 2004, pp. 176–77.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wong, J. Y. Deadly Dreams: Opium and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. ISBN 9780521526197.

- ^ a b "Bombardment at Canton". Morning Journal. 19 January 1857. p. 3.

- ^ David, Saul (2007). Victoria's Wars: The Rise of Empire. London: Penguin Books. pp. 360–61. ISBN 978-0-14-100555-3.

- ^ Hsü 2000, p. 206.

- ^ Hevia 2003, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Tsai, Jung-fang. [1995] (1995). Hong Kong in Chinese History: community and social unrest in the British Colony, 1842–1913. ISBN 0-231-07933-8

- ^ "The Anglo-French Occupation of Canton, 1858–1861" (PDF). Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch.

- ^ Hsü 2000, p. 207.

- ^ John Thomson 1837–1921, Chap on Hong Kong, Illustrations of China and Its People (London, 1873–1874)

- ^ Speeches on Questions of Public Policy by Richard Cobden

- ^ Ye Shen, Shirley; Shaw, Eric H. "The Evil Trade that Opened China to the West" (PDF). p. 197. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- ^ Hsü 2000, p. 212–13.

- ^ Greenwood, ch. 12

- ^ China: Being a Military Report on the North-eastern Portions of the Provinces of Chih-li and Shan-tung, Nanjing and Its Approaches, Canton and Its Approaches: Together with an Account of the Chinese Civil, Naval and Military Administrations, and a Narrative of the Wars Between Great Britain and China. Government Central Branch Press. 1884. p. 28.

- ^ Albert H. Yee (1989). A People Misruled: Hong Kong and the Chinese Stepping Stone Syndrome. API Press. p. 59.

- ^ Hsü 2000, pp. 214–15.

- ^ Hsü 2000, p. 215.

- ^ a b Endacott, G. B.; Carroll, John M. (2005) [1962]. A biographical sketch-book of early Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-742-1.

- ^ Hsü 2000.

- ^ Hsü 2000, p. 219.

- ^ Kathleen L. Lodwick (5 February 2015). Crusaders Against Opium: Protestant Missionaries in China, 1874–1917. University Press of Kentucky. p. 86. ISBN 978-0-8131-4968-4.

- ^ Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy (2009). Opium: Uncovering the Politics of the Poppy. Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-674-05134-8.

- ^ Dr Roland Quinault; Dr Ruth Clayton Windscheffel; Mr Roger Swift (28 July 2013). William Gladstone: New Studies and Perspectives. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-4094-8327-4.

- ^ Ms Louise Foxcroft (28 June 2013). The Making of Addiction: The 'Use and Abuse' of Opium in Nineteenth-Century Britain. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-4094-7984-0.

- ^ William Travis Hanes; Frank Sanello (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-4022-0149-3.

- ^ W. Travis Hanes III; Frank Sanello (1 February 2004). The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-4022-5205-1.

- ^ Peter Ward Fay (9 November 2000). The Opium War, 1840-1842: Barbarians in the Celestial Empire in the Early Part of the Nineteenth Century and the War by which They Forced Her Gates Ajar. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-8078-6136-3.

- ^ Anne Isba (24 August 2006). Gladstone and Women. A&C Black. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-85285-471-3.

- ^ David William Bebbington (1993). William Ewart Gladstone: Faith and Politics in Victorian Britain. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8028-0152-4.

Sources

- Hanes, William Travis; Sanello, Frank (2004). Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another. Sourcebooks. ISBN 9781402201493.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hevia, James Louis (2003). English lessons: the pedagogy of imperialism in nineteenth-century China. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822331889.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hsü, Immanuel C. Y. (2000). The Rise of Modern China. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512504-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Bickers, Robert A. (2011). The scramble for China: foreign devils in the Qing empire, 1800–1914. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713997491.

- Beeching, Jack. The Chinese Opium Wars (1975), ISBN 0-15-617094-9

- Chan, May Caroline. "Canton, 1857." Victorian Review 36.1 (2010): 31–35.

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria's Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496. ISBN 0-75095-685-2.

- Leavenworth, Charles S. The Arrow War with China (1901) online free.

- Henry Loch, Personal narrative of occurrences during Lord Elgin's second embassy to China 1860, 1869.

- Lovell, Julia (2011). Opium War. London: Picador. ISBN 9780330537858.

- Ringmar, Erik (2013). Liberal Barbarism: The European Destruction of the Palace of the Emperor of China. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|chapterurl=(help) - Spence, Jonathan D. (2013). The search for modern China. New York: Norton. ISBN 9780393934519.

- Wong, J. Y. (1998). Deadly dreams: opium, imperialism, and the Arrow War (1856–1860) in China. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521552559.

- Wong, J. Y. "Harry Parkes and the 'Arrow War' in China," Modern Asian Studies (1975) 9#3 pp. 303–320.

- Wong, John Yue-wo. Deadly dreams: Opium and the Arrow war (1856–1860) in China (Cambridge UP, 2002).

External links

Works related to China and the Attack on Canton at Wikisource

Works related to China and the Attack on Canton at Wikisource