COVID-19 pandemic in Texas

| COVID-19 pandemic in Texas | |

|---|---|

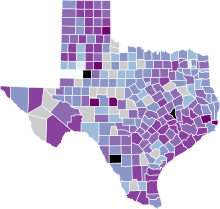

Map of the outbreak in Texas by confirmed new infections per 100,000 people over 14 days (last updated March 2021)

1,000+

500–1,000

200–500

100–200

50–100

20–50

10–20

0–10

No confirmed new cases or no/bad data | |

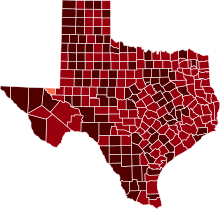

Map of the outbreak in Texas by confirmed total infections per 100,000 people (last updated March 2021)

10,000+

3,000–10,000

1,000–3,000

300–1,000

100–300

30–100

0–30

No confirmed infected or no data | |

| Disease | COVID-19 |

| Virus strain | SARS-CoV-2 |

| Location | Texas, U.S |

| Index case | San Antonio (evacuee), Fort Bend County (non-evacuee) |

| Arrival date | March 4, 2020 |

| Confirmed cases | 513,575 [1] |

| Hospitalized cases | 6,879 (current)[1] |

| Recovered | 375,760 (estimate) |

Deaths | 9,289 [2] |

| Government website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on the |

| COVID-19 pandemic |

|---|

|

|

|

|

The COVID-19 pandemic reached the U.S. state of Texas by March 2020. As of August 13, 2020[update], Texas public health officials reported 6,755 new cases of COVID-19 and 255 deaths, increasing the state's cumulative totals since the start of the pandemic to 513,575 cases and 9,289 deaths, with 4.3 million tests completed for COVID-19.[1] During the month of July both the new COVID-19 case rate and the death rate more than doubled in Texas.[1] The 7 day moving average of new cases increased nearly five-fold between the first week of June and the 1st week of August, rising from 1534 new cases per week to 7285 cases.

Prior to March, there were several suspected cases of COVID-19 in the state that tested negative for the virus beginning on January 23. Three Texas airports conducted enhanced screening for the disease in January, with Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport among them also receiving diverted flights from China. The first documented case in Texas was confirmed on February 13 among U.S. nationals evacuated from China to Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland beginning in early February; however, retrospective analyses have suggested a much earlier origin than previously thought. The first documented case of COVID-19 in Texas outside of evacuees at Lackland was confirmed on March 4 in Fort Bend County, and many of the state's largest cities recorded their first cases throughout March. Evidence of community transmission within the state was identified by March 11. The state recorded its first death associated with the disease on March 17 in Matagorda County. By March 26, there were over 1,000 cumulative confirmed cases of the virus in the state, further exceeding 10,000 on April 9. Despite early increases, the number of confirmed infections in Texas remained below the ten most impacted states by the detected number of infected until the middle of May 2020, although testing was initially very limited. A sustained increase in new case confirmations and hospitalizations began after mid-May and has continued into July with days frequently setting records for daily case totals.

Texas Governor Greg Abbott declared a state of disaster on March 13 and the Texas Department of State Health Services declared a public health disaster six days later for the first time since 1901. Counties, cities, and other local jurisdictions began implementing stay-at-home and shelter-in-place orders as the virus spread throughout March. The state government began directing the closure of some businesses beginning on March 19 and a statewide stay-at-home order went into effect on March 26 amid other restrictions on activities and businesses. Abbott and his administration began directing a "reopening" of the state's economy in April, with the state entering three phases of eased restrictions in May and June; Texas was one of the first states in the country to begin reopening. During both the initial round of pandemic-related restrictions and the reopening phases in May and June, local governments and the state government were frequently discordant over their pandemic response due to an insistence from municipal governments to strengthen restrictions and a resistance to enact such restrictions at the state level. Pandemic restrictions sparked protests in Texas and throughout the U.S. while the economic reopening was criticized as being done too early and too quickly. The Texas Tribune described the overall response as a "patchwork" of inconsistent and incongruent policies. The acceleration of the pandemic's spread in May and June led the state to pause the economic reopening on June 25, with the government subsequently reinstating restrictions. A statewide mask mandate was imposed on July 2, with Abbott cautioning on July 10 that "the next step would have to be a lockdown" should cases continue to increase.

The pandemic has caused significant socioeconomic impacts on the state. In March, employment contracted by 4.7 percent, representing the largest contraction since the Great Recession.[3] The state's unemployment peaked at 13.5 percent in May 2020, and as of July 4, 2020, 2.8 million Texans had filed for unemployment benefits since mid-March.[4] The Texas Workforce Commission announced that the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation, which provided an additional $600 per week to claimants who faced pandemic-related loss of work, would end the week of July 25 with only state unemployment benefits continuing on for the duration of their claim.[5]

An estimated 12 percent of restaurants were closed permanently.[citation needed] Higher education and primary and secondary schools ended in-person classes and moved to online instruction with ramifications for both school terms in 2020 and 2021. All major sports leagues suspended play. The risk of infections led to the cancellation of high-profile events including the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, South by Southwest (SXSW), Austin City Limits, and the Texas State Fair.

As of August 2020, Texas currently has the third highest number of confirmed cases in the United States.[6]

Background and evacuee cases

A pandemic involving the spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), began in 2019 with the outbreak first identified in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.[7][8][9] The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30 and evaluated it as a pandemic on March 11.[10][11] The first case in the United States was reported in Snohomish County, Washington, on January 20,[12] and the Trump administration declared a public health emergency on January 31.[13]

The initial spread of COVID-19 in Texas may have begun prior to the first contemporaneously confirmed case. In January, February, and March 2020, 1,473 more Texans died compared to the January–March average for 2014–2019. While the Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) attributed 41 of these deaths to COVID-19, USA Today reported that doctors believed additional COVID-19 deaths may not have been accounted for due to limited testing early in the pandemic.[14] In one specific case, Bastrop County judge Paul Pape reported symptoms starting February 9.[15] The infection risk of COVID-19 in Texas was initially expected to be low in mid-January, with risks limited to travelers recently returning from China.[16] KWKT-TV in Waco reported that the virus was "no cause of concern in Central Texas" according to local doctors amid the ongoing flu season.[17] On January 23, a student at Texas A&M University was isolated and monitored by the Brazos County Health District after returning from Wuhan, China, and presenting with a respiratory illness; at the time, there was only one known case of COVID-19 in the United States.[18][19][20] They were the first person in Texas contemporaneously identified as potentially contracting SARS-CoV-2.[21] Medical supply stores in the Brazos Valley experienced medical mask shortages as demand increased in response to the first suspected case.[22] Over the next four days, Texas health officials identified another three suspected cases of COVID-19 meeting testing criteria, including a student at Baylor University; all four tested negative for the virus after samples were delivered to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, leaving no confirmed cases in Texas.[23][24][25][21]

The Tarrant County Health Department activated its operations center on January 24. Paramedics in the Metroplex increased usage of personal protective equipment (PPE) and adjusted their screening procedures for respiratory illnesses.[26][27] Hospital protocols were updated to isolate patients presenting to emergency rooms with COVID-19 symptoms and with recent travel to Wuhan.[27][28] While the CDC did not initially designate Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport to carry out "enhanced screening" of passengers for COVID-19, the airport began coordinating with local hospitals and health departments in late-January.[26] The CDC later implemented COVID-19 screenings at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport, George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston, and El Paso International Airport, with screenings beginning "on a rolling basis" according to Nancy Messonnier of the CDC. These locations were designated as three of twenty CDC Quarantine Stations across the U.S. due to their frequent use as points of arrival for international travelers.[29][30] The Allied Pilots Association, a labor union representing pilots serving American Airlines, sued American Airlines on January 30 through Dallas County to end all flights to China;[31][32] the airline acquiesced on February 4.[33] On February 3, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security named Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport as one of 11 airports receiving rerouted flights from China.[34] Health workers from the CDC were dispatched to the airport to screen passengers for COVID-19 symptoms.[32] Screenings were also expanded to border crossings between the U.S. and Mexico at El Paso.[35]

Texas A&M University suspended all undergraduate travel to China on January 28 and allowed only essential travel to China for faculty, staff, and graduate students.[36] Baylor University and the University of Texas also temporarily banned university-sponsored travel to China with the exception of essential travel.[37] Two people in the Dallas area were monitored for possible contraction of COVID-19 on January 31.[38] Another patient was reported as a possible carrier in Beaumont on February 5,[39] and six were being monitored in Austin.[40] Some residents in San Antonio began 14-day self-quarantines.[41] Local health departments, hospitals, and schools in Texas continued to revise their COVID-19 protocols through February.[42][43][44][45] Stocks of N95 masks at clinics in Central Texas were low due to high demand as the pandemic escalated.[46]

Evacuee quarantines and cases

As part of COVID-19 evacuations of American nationals in China, the Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHS) and U.S. Department of Defense agreed on February 1 to house at least 250 evacuees for up to a month at Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland (JBSA-Lackland) near San Antonio as one of four reception centers across the country.[47][48] JBSA–Lackland was chosen due to its large housing capacity, available space, and proximity to medical facilities in San Antonio.[49] The evacuees were flown to U.S. bases on chartered flights operated out by the U.S. Air Force, with the first flight landing in San Antonio on February 5.[50][51] On February 13, the CDC confirmed one of the individuals quarantined at JBSA-Lackland contracted COVID-19, representing the 15th confirmed case in the U.S.[50] They were among 91 people on a flight arriving at JBSA–Lackland on February 7.[52] After an outbreak of COVID-19 impacted the Diamond Princess cruise ship in February, the U.S. State Department arranged for two charter flights to evacuate U.S. nationals to two U.S. locations, including JBSA–Lackland. Fourteen of the evacuees tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 after being initially asymptomatic,[53] of which seven landed in JBSA–Lackland before being transferred to the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska.[54] On February 21, the CDC announced that another two individuals tested positive for the virus among Diamond Princess evacuees quarantined at JBSA–Lackland, bringing the San Antonio and statewide case total to three.[55][56] By February 24, the case total in Texas rose to six, all of whom were quarantined at JBSA–Lackland;[57] a total of 11 people at the base were later confirmed as infected, with 9 from the cruise ship and 2 from Wuhan.[58]

Evacuees quarantining at JBSA–Lackland were sent to the Texas Center for Infectious Disease in San Antonio, with 22 beds at the hospital reserved for suspected COVID-19 patients and those presenting with "mild symptoms." By February 19, JBSA–Lackland was supporting the quarantines of 234 people, with 144 from the Diamond Princess cruise ship and 91 from Hubei Province. Nelson Wolff, the Bexar County Judge, criticized the movement of evacuees to hospitals before definitive diagnoses in a letter sent to U.S. Representative Chip Roy. Bexar County Commissioner Tommy Calvert also criticized the decision to move patients out of JBSA–Lackland, stating that the move created "additional vectors for the virus to spread into the civilian population."[49] On February 20, the evacuees from Hubei Province at the base were released after showing no symptoms for 14 days.[59] Despite two earlier negative tests for the virus, one person had a "weakly positive" test after their release from JBSA–Lackland and were moved back to the facility for quarantine on March 1 following 12 hours out of quarantine. Texas Governor Greg Abbott, San Antonio mayor Ron Nirenberg and U.S. Representative Joaquin Castro criticized the CDC's release of the patient; Castro asked the U.S. House of Representatives to investigate CDC patient treatment protocols, with similar requests from U.S. Senators John Cornyn and Ted Cruz and U.S. Representative Lloyd Doggett.[60][61][62] The release prompted Nirenberg to declare a public health emergency for San Antonio on March 2.[63] A federal judge denied an injunction filed by the city of San Antonio against the CDC "demanding more rigorous testing" before releasing asymptomatic individuals at JBSA–Lackland.[64] The CDC modified their quarantine protocol in the aftermath of the incident to require "two sequential negative tests within 24 hours" prior to releasing quarantined individuals.[65]

Epidemiology

The first positive test result for COVID-19 in Texas, outside of the evacuees quarantined at JBSA–Lackland from China and the Diamond Princess cruise ship, was reported by the DSHS on March 4 and involved a resident of Fort Bend County.[66][67] The patient was a man in his 70s and had traveled on the Nile River cruise ship MS A'sara in Egypt.[67][68] A total of 12 positive test results were reported in Fort Bend and Harris counties from travelers aboard the same ship.[69][70] The first case of possible community spread—where the source of infection is unknown—was reported by public health officials on March 11, involving a man in his 40s in Montgomery County; he had recently attended a barbecue at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo on February 28.[71][72][73][74] The first death in Texas identified in connection with COVID-19 occurred on March 14 from a man in his 90s at the Matagorda Regional Medical Center; Matagorda County officials reported the death on March 15 and the DSHS confirmed it the following day.[75][76][77] According to the DSHS, the state exceeded 100 total cases of COVID-19 by March 19 and 1,000 cases by March 26.[1] By the end of March 2020, there were 3,266 known cases of COVID-19 and 41 fatalities in Texas, with nearly half of the state's counties reporting at least one case.[78] An analysis of the first month of COVID-19's spread in Texas, published in the Journal of Community Health, found that while the total case counts were highest in the state's metropolitan areas, the highest incidence rates of the disease per capita occurred in Donley County, with 353.5 cases per 100,000 people. The case fatality rate (CFR) was 10.3 percent in Comal County; high CFR counties had "a higher proportion of non-Hispanic Black residents, adults aged 65 and older, and adults smoking, but lower number of ICU beds per 100,000 population, and number of primary care physicians per 1000 population."[75]

The cumulative number of COVID-19 cases confirmed by the DSHS reached 10,000 on April 9 and 100,000 on June 19. The number of confirmed fatalities eclipsed 100 on April 4 and 1,000 on May 9.[1] Counties that adopted shelter-in-place orders early showed a 19–26 percent decrease in COVID-19 case growth 2.5 weeks following the enactment of those orders according to an analysis published in the National Bureau of Economic Research. The same analysis found that such orders in urbanized counties accounted for 90 percent of attenuated case growth in the state by May.[79] A surge in new COVID-19 cases began in June with large increases in the state's major cities and within a younger population compared to the beginning of the pandemic.[80][81]

Timeline

Early origins

The initial origin of community spread in Texas remains unclear, but numerous anecdotal accounts by those later confirmed have included onset dates as early as December 28 in Point Venture, and retrospective analyses have found unexplained statistical increases in deaths during this time.[14][82][15] Testing capacity across the state remained extremely limited until after the first recorded cases were announced.[14]

March

March 2: Research from Austin Public Health found 68 COVID-19 patients in Central Texas began reporting symptoms dating back to this time.[83] San Antonio Mayor Nirenberg issues a public health emergency after an individual positive for the virus is mistakenly released from quarantine at JBSA–Lackland.[63]

March 4: The DSHS reports a presumptive positive test result for COVID-19 from a resident of Fort Bend County in the Houston area. A man in his 70s, he is the first known positive case of the disease in Texas outside of those evacuated from Wuhan and the Diamond Princess cruise ship.[66] The patient had recently traveled to Egypt and was hospitalized.[67] DSHS commissioner John Hellerstedt calls the confirmation a "significant development" but that "the immediate risk to most Texans is low."[66]

March 5: At least eight cumulative cases, including both positive and presumptive positive cases, are identified in the Houston area. The cases involve individuals in the counties of Fort Bend and Harris counties. All individuals with confirmed cases were part of a group that traveled to Egypt in February, including the first confirmed case in Fort Bend County. The travel group rode aboard the Nile River cruise ship MS A’sara.[84][85][86] Additional individuals are also investigated as possible carriers in the Houston area in connection with the Egypt trip.[86] The state announces six public health laboratories within its Laboratory Response Network are capable of testing for COVID-19.[87]

March 6: Mayor Steve Adler of Austin declares a local disaster and cancels South by Southwest for the first time in its history.[88]

March 8: JBSA–Lackland receives around 100 evacuees from the cruise ship Grand Princess following a localized outbreak on board.[89][90] Rice University becomes the first university in the state to enact significant cancellations, suspending in-person classes and undergraduate labs during the week in response to an employee testing positive in connection with the viral cluster that traveled to Egypt.[91]

March 9: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 10.[1] A resident in his 30s of Frisco in Collin County, a suburb of Dallas, receives a presumptive positive test for the virus after recently traveling to Silicon Valley in California; he is the first case identified in the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area.[92][93][94] His wife and 3-year-old child later contracted the disease, with the latter among the youngest confirmed to have the virus in the U.S.[72]

March 10: The first two presumptive positive cases of COVID-19 are reported in Dallas County, composed of a 77-year-old frequent traveler and a close contact.[95] Tarrant County also reports its first presumptive positive case, involving a recent traveler to a conference in Kentucky in late February.[96] Abbott and the Texas Department of Insurance request health insurers and health maintenance organizations (HMOs) to waive COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment costs.[97][98]

March 11: Local health officials report a positive test for COVID-19 in Montgomery County; they are identified as the first possible case of community spread—not directly related to travel or known contact with positive travelers—in Texas and in the Houston area. The patient's attendance of a barbecue at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo on February 28 is reported as a possible but unconfirmed source of the virus.[74] The city of Houston orders the Houston Livestock Show and Radio to close after announcing an emergency health declaration.[99] Lakewood Church suspends public services within the church and moves its services online.[100] Montgomery Independent School District in the Houston area and Alvarado Independent School District in the Dallas area become the first two public school districts in Texas to temporarily close classes over COVID-19, affecting approximately 12,400 students across 17 schools.[101]

March 12: After traveling to Barcelona and Paris between March 4–10, a 29-year-old-man becomes the first reported case of COVID-19 in Bell County.[102] Five people test positive for the virus in Dallas County, with one without recent travel history; the individual is the first case of community spread in North Texas, prompting a local disaster declaration for Dallas County.[103]

March 13: San Antonio reports its first positive case of COVID-19 with an individual not associated with the quarantining evacuees at JBSA–Lackland. Mayor Nirenberg declares a public health emergency and limits gatherings of more than 500 people for one week.[104] The first three cases of COVID-19 are also identified in the Austin area. University of Texas Gregory L. Fenves announces that his wife is among the positive cases following a trip to New York City for a university function with alumni and students.[105][106] A man in his 40s with recent domestic travel is identified as the first confirmed case of COVID-19 in the El Paso area.[107] Abbott declares a state of disaster for all counties in Texas, invoking emergency powers for the his administration, and orders state employees to work from home. Day cares, nursing homes, and prisons are asked to limit visitations.[108][109] The state's first mobile testing center for COVID-19 opens in San Antonio.[110] Colleges and universities throughout the state extend their spring breaks with some transitioning to online instruction, including Baylor University, the University of Houston, the University of North Texas, the University of Texas at Austin, Texas State University, and Texas Tech University.[111] School districts also announce temporary suspensions of classes statewide.[112][113][114]

March 14: Between March 14–19, some students from the University of Texas at Austin take a trip to Cabo San Lucas, Mexico, for spring break; on March 27, a student has a positive test result for SARS-CoV-2 after returning from Cabo San Lucas. A contact tracing investigation conducted by the COVID-19 Center at the University of Texas Health Austin concludes on April 5, with viral tests on 231 students. Among the sample, 60 of the 183 travelers to Cabo San Lucas test positive for the virus.[115] Abbott directs the Texas Medical Board and Texas Board of Nursing to expedite temporary licensing for out-of-state medical professionals while the state remains in a state of disaster.[116]

March 15: Texas Health and Human Services issues guidelines for nursing facilities outlining procedures for COVID-19 screening and restricting personnel and visitors at 1,222 nursing facilities in the state.[117]

March 16: A 40-year-old elementary school teacher is identified as presumptive positive for SARS-CoV-2, becoming the first case of the virus in Laredo. The patient had no history of travel to affected areas.[118] Abbott waives requirements for the State of Texas Assessments of Academic Readiness (STAAR)—standardized tests typically administered in Texas schools.[119] Parts of the Texas Open Meetings Act, which increases transparency for government meetings, are suspended to allow for telephone and video conferences.[120] The mayors of Dallas and Houston order the closure of various social establishments for at least a week; restaurants in Dallas and Harris Counties are limited to drive-through service.[121] San Antonio Mayor Nirenberg reduces the social gathering cap to 50 people.[122]

March 17: DSHS reports that a man in his 90s in Matagorda County died of COVID-19 after being hospitalized, becoming the first official COVID-19 fatality in Texas.[76] Two unrelated travelers are identified as the first two positive confirmations of COVID-19 in Lubbock; neither were hospitalized but self-quarantined at home.[123] The Brazos County Health District confirms the first case of COVID-19, a woman in her 20s, in Brazos County.[124] The Texas National Guard is activated, making Texas the 21st U.S. state to activate their National Guard; the security force is not yet deployed.[125] Abbott grants waivers to hospitals to bolster unused bed capacity without applying or paying added fees.[126] Abbott also asks the Small Business Administration to declare an Economic Injury Disaster Declaration for the state;[127] eligibility is granted three days later.[128] Texas-chartered banks restrict indoor access. Austin and El Paso close their bars, with Austin also closing its restaurants.[129]

March 18: Amarillo and Beaumont confirm their first positive COVID-19 cases, with Amarillo reporting two and Beaumont reporting one.[130][131] The Waco–McLennan County Health District announces the first six cases in McLennan County; five of the cases are identified as recent travelers.[132] The state closes all Texas Department of Public Safety Driver License Offices, excepting those seeking their first commercial driver's license, as Abbott partially suspends the Texas Transportation Code to delay expiration dates on driver's licenses.[133] Local governments are also authorized to delay elections slated for May 2 to November.[134]

March 19: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 100.[1] Cameron County reports the first positive case of COVID-19 in the Rio Grande Valley, involving a 21-year-old traveler to Ireland and Spain from mid-March.[135] The first six cases of community transmission in San Antonio are documented.[136] Austin Public Health reports evidence of community spread in Travis County as the county's cumulative case count nearly doubles in a single day.[137] An outbreak begins at the Denton State Supported Living Center in Denton, with the number of positive test results increasing to 55 residents and 67 employees of facility by May 21.[138][139] The DSHS declares a public health disaster, marking the first such declaration since 1901.[140] DSHS Director Hellerstedt issues the disaster declaration as the disease "has created an immediate threat, poses a high risk of death to a large number of people and creates a substantial risk of public exposure because of the disease’s method of transmission and evidence that there is community spread in Texas."[141] Abbott issues four executive orders to ban gatherings of more than 10 people; discourage eating and drinking at bars, food courts restaurants, and visiting gyms (and close bars and restaurant dining rooms); proscribe visitation of nursing homes, retirement centers, and long-term care facilities with exception of providing critical care; and temporarily close all Texas schools.[142] The Texas Supreme Court halts most eviction proceedings statewide until April 19.[143]

March 20: Abbott postpones runoff elections scheduled for May 26 to July 14.[144] Prisoner healthcare fees related to COVID-19 are suspended.[145] Healthcare providers begin to delay elective medical procedures, including Houston Methodist and the Memorial Hermann Health System.[146]

March 21: Officials in Corpus Christi and Nueces Couty confirm the first case of COVID-19 in the area. The individual is believed to have contracted the virus following a one-day business trip to Houston.[147] A resident of the Southeast Nursing and Rehabilitation Center in San Antonio is hospitalized and tests positive for COVID-19.[148] An outbreak at the nursing home leads to at least 75 infections and 12 fatalities, prompting investigations by local and state officials.[149][150][151] The nursing home had been recently evaluated as having poor sanitation and infection control in federal reports.[152][148] Abbott suspends nursing regulations to increase the nursing workforce, including nurses with inactive licenses and retired nurses to reactivate their licenses.[153] Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins proscribes elective medical procedures in the county through April 3.[154]

March 22: Abbott issues an executive order allowing hospitals to treat two patients in the same room and ordering the suspension of "elective or non-essential" medical procedures.[155] Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton clarifies the following day that the order extends to abortions, prompting representatives of abortion providers in Texas to seek a restraining order.[156][157] Federal Judge Earl Leroy Yeakel III of the Western District of Texas blocks the abortion ban on March 30;[158] the block is overturned by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on March 31.[159] A Supply Chain Strike Force is formed under the chairmanship of Keith Miears to manage healthcare logistics between public and private sectors.[160]

March 23: The Texas Department of Criminal Justice confirms a positive test result for a 37-year-old prisoner at the Lychner State Jail, marking the first case of COVID-19 from a Texas inmate.[161] The CDC disburses $36.9 million to Texas as part of the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act, 2020 (CARES Act); the DSHS allocates $19.5 million to 43 local health departments and the remainder to operations support and state response.[162] Abbott asks President Trump to issue a disaster declaration for the state of Texas with crisis counseling and direct federal assistance for all counties.[163] A "shelter-at-home order" goes into effect for Dallas County.[164]

March 24: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 500 and the cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 fatalities reported by the DSHS surpasses 10.[1] Abbott issues an executive order requiring hospitals to report bed capacity to the state health department daily and healthcare providers to report COVID-19 testing. The Supply Chain Strike Force orders $80 million in supplies, including 200,000 masks daily.[165] Stay-at-home orders go into effect in Bexar, Harris, and Travis counties.[166][167][168]

March 25: President Trump approves a federal disaster declaration for the state of Texas.[169] The declaration obligates $628.8 million in public assistance grants from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).[170]

March 26: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 1,000.[1] An executive order issued by Abbott mandates visitors flying to Texas from Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and New Orleans, Louisiana, to self-quarantine for 14 days.[171] Modelling from a team of researchers at the University of Texas at Austin was presented to the government of Austin. The model projected epidemiological outcomes of school closures and varying degrees of social distancing compliance out to August 17, starting with a basic reproduction number of 2.2, an average incubation period of 7.1 days, a doubling time of 4 days, and the initial prevalence of COVID-19 in the region. It indicated that healthcare capacity of the Greater Austin metropolitan area would be exceeded if "extensive social distancing measures" were not implemented. The simulation estimated 87,501 cumulative hospitalizations and 10,908 cumulative deaths in the absence of social distancing measures or school closures, compared to 3,254 cumulative hospitalizations and 267 cumulative deaths with both school closures and 90 percent social distance compliance; of the four social distancing scenarios modeled, only the 90 percent compliance scenario indicated hospitalizations within capacity through August 17.[172]

March 27: Three brigades from the Texas National Guard are deployed to assist drive-through COVID-19 testing sites.[173] The U.S. government authorizes the Texas Health and Human Services Commission to extend coverage for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and Medicaid.[174]

March 28: The number of confirmed cases in Houston triples from 69 to 232.[175] A first case of COVID-19 is reported at The Resort, a nursing home in Texas City. By April 3, 83 people at The Resort test positive for the virus.[176] Renewal regulations for pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and pharmacy technician trainees are waived to bolster pharmaceutical services.[177]

March 29: The state's mandatory 14-day quarantines are expanded to include air travelers entering Texas from the states of California and Washington, the cities of Atlanta, Detroit, and Miami, and road travelers entering Texas from Louisiana.[178][179] The Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center in Dallas, with capacity for at least 250 beds, is designated as Texas's first ad hoc treatment facility COVID-19.[179] Initial modelling from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IMHE) at the University of Washington projects 6,029 deaths in the state by August 4 with peak hospital resource use and daily fatalities on May 5–6.[180]

March 31: An executive order from Abbott amends earlier social distancing policies, limiting activities susceptible to the spread of COVID-19 and giving police power to apprehend violators effective through April 30; the order does not apply to activities classified as essential. Schools are ordered closed to classroom attendance until May 4.[181][182] Across the state, 51 counties are under stay-at-home orders by the end of March 2020.[183]

April

April 1: Thirteen counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[152] The Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) begins rolling out enforcement of travel restrictions ordered by Abbott, sending troopers to airports to direct travelers to quarantines.[184] El Paso expands restrictions on most gatherings of any size and closes recreational areas.[152]

April 2: Eight counties confirm cases of COVID-19 for the first time.[185] Data from the DSHS indicates COVID-19 fatalities in the state quadrupled over the preceding week.[186]

April 3: Two counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[187] Harris County becomes the first county to document over 1,000 total cases, with the Houston area accounting for 38 percent of cases in the state.[187][188]

April 4: The cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 fatalities in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 100.[1] Six counties report cases for the first time.[189]

April 5: Analysis from the University of Texas estimate a 9 percent likelihood of undetected outbreaks occurring in counties without reported cases.[190] Abbott permits new medical professionals to enter the workforce with an emergency license under supervision without taking a final licensure exam.[191] The Texas DPS establishes checkpoints along the state border with Louisiana on Interstate 10 following the mandatory quarantine order for road travelers entering from Louisiana.[192]

April 6: Six counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[193] Abbott reports that 1.68 million masks and 210,000 face shields have been distributed in the state since March 30, with another 2.5 million masks awaiting distribution and 3 million masks pending delivery.[194] Harris County begins constructing a medical shelter at NRG Park to handle an influx of COVID-19 patients, with approval later given for a $60 million backup field hospital.[195][196]

April 7: Four counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[150] All Texas state parks operated by Texas Parks and Wildlife and historical sites operated by the Texas Historical Commission close to prevent the spread of COVID-19.[197] The Texas Department of Criminal Justice enlists inmates at 10 prison factories to produce up to 20,000 cloth masks daily.[198] Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick forms a task force for reopening businesses.[199]

April 8: The DSHS reports over 1,000 cases in a single day for the first time, with 1,092 on April 10.[1] Four counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[200] The U.S. Department of Agriculture authorizes Texas Health and Human Services to grant SNAP recipients the maximum allowable allotment from the program based on family size, amounting to over $168 million in emergency benefits.[201]

April 9: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 10,000.[1] Three counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[202] The Texas Health and Human Services Commission reports that COVID-19 cases have been confirmed at approximately 13 percent of the 1,222 nursing homes in the state.[203] The Dallas City Council approves $4.3 million to use recreational vehicles and hotel rooms to quarantine first responders.[202]

April 10: The DSHS reports 1,441 new cases, representing the highest single-day increase until mid-May.[1] Six counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[151] The Austin City Council allocates $15 million from city reserves to provide monetary assistance and food service through Austin Public Health.[151]

April 11: Abbott extends the state's disaster declaration, issued on March 13, for an additional 30 days. The declaration prolongs operation of the State Operations Center and access to the Strategic National Stockpile.[204]

April 13: Abbott announces his intention to reopen private businesses in the state.[205][206] The city of Houston relaxes testing requirements for COVID-19, allowing anyone to get tested regardless of symptoms.[207]

April 14: Three counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time. Texas airports receive $811.5 million in support from the CARES Act.[208]

April 15: Three counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[209] Abbott announces that the Texas Public Safety Office will allocate $38 million in federal funding to local governments.[210]

April 16: Seven counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time. Dallas County and San Antonio begin mandating face masks. The Texas Frontline Child Task Force apportions $200 million in funding to support child care costs for essential workers.[211]

April 17: A privately homeless shelter in Dallas reports the first 17 of ultimately 38 positive results for COVID-19.[212] Abbott announces the start of his plan to reopen the Texas economy, citing a "semi-flattened curve" of COVID-19 cases in the state.[213] The reopening is outlined in three executive orders issued by Abbott that allows for state parks to open under social distancing regulations on April 20, limited nonessential surgeries at hospitals beginning after April 21, and product pickup at retail stores beginning on April 24.[214] The reopening process also establishes the Strike Force to Open Texas, an advisory panel to Abbott for reopening economy. The panel is led by James Huffines with Mike Toomey as its chief operating officer; its consulting members are all members of the Republican Party. The panel also consists of a medical team and a special advisory council.[215] Abbott also calls for public schools to remain closed for the rest of the 2019–2020 academic year.[216]

April 18: Three counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[212]

April 20: Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) reports 24 detainees have COVID-19 at the Prairieland Detention Center in Alvarado.[217] Over 1,200 personnel on 25 COVID-19 mobile testing teams from the Texas National Guard are deployed around the state at locations determined by the DSHS.[218]

April 22: Two counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[219] Harris County begins mandating the use of face coverings for 30 days, enforceable by a $1,000 fine.[220]

April 23: The Texas Health and Human Services Commission receives $54 million through the CARES ACT to provide COVID-19 support for disability and geriatric services.[221]

April 24: Two counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[222]

April 27: Pursuant to the executive order establishing the Strike Force to Open Texas, Abbott releases the Texas Governor's Report to Open Texas, putting forth a phased approach to reopen the state's economy, outlining a three-phase plan to reopen and relax restrictions on Texas businesses in addition to providing guidance on newly released social protocols from the governor and chief officers of the Strike Force to Open Texas. Abbott also outlines three phases for expanding contract racing.[223][224] The limits and timetable specified in the state reopening plan overrule local jurisdictions.[225][226] Baylor University President Linda Livingstone announces the university's intention to provide in-person instruction and student residency in fall 2020.[227]

April 28: Two counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[228]

April 30: Two counties report COVID-19 cases for the first time.[229]

May

May 2: Amarillo Mayor Ginger Nelson announces that a federal team will be deployed in the city to quell quickly rising infection rates in the region.[230] The CDC assumes control of investigations and testing in the Amarillo area at Nelson's behest.[231]

May 5: Abbott modifies his earlier reopening timetable, allowing barbershops, hairdressers, and nail salons to begin reopening on May 8 while maintaining social distancing. Gyms and exercise facilities are allowed to reopen beginning May 18 while operating at quarter occupancy.[232] "Hybrid" graduation ceremonies are also permitted by the state while following social distancing guidelines.[233] The governor also announces the implementation of "Surge Response Teams" for outbreaks arising during reopening.[234] The Texas Office of Court Administration provides guidance allowing courts to begin in-person non-jury proceedings on and after June 1.[235]

May 6: The state, in cooperation with the OneStar Foundation, initiates the Texas COVID Relief Fund as a mechanism for granting local organizations funds.[236] A $15 million relief fund is approved by the Houston City Council to assist renters with overdue payments following wage losses.[237]

May 8: The cumulative number of confirmed COVID-19 fatalities in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 1,000.[1] Stay-at-home orders in Austin are extended to the end of May.[238]

May 11: Following federal recommendations to test nursing home residents, Abbott mandates COVID-19 testing for all nursing home residents and personnel, covering approximately 230,000 people.[239] Local fire departments join the nursing home testing efforts four days later following a collaboration between several state agencies.[240] San Antonio extends free COVID-19 testing to asymptomatic individuals.[241]

May 12: Abbott extends the ongoing disaster declaration for the state for a second time following its initial issuance on March 13.[242] The Texas Health and Human Services Commission (HHSC) is authorized by the USDA to provide $285 per child for families without access to free or discounted school meals due to COVID-19, amounting to over $1 billion for the state in food benefits.[243] Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton pens letters to Bexar, Dallas, and Travis counties and the mayors of Austin and San Antonio calling their actions "strict and unconstitutional" warning them not to implement restrictions more stringent than the state.[244]

May 13: Members of the Texas National Guard are deployed to disinfect nursing homes and assisted living facilities, which at the time have accounted for 47 percent of the state's deaths.[245]

May 16: The DSHS reports 734 new cases of COVID-19 in the Amarillo area following targeted testing of meatpacking facilities in the region carried out by a surge response team beginning on May 4.[246][247] The influx of cases contributes to the largest single-day increase in COVID-19 cases in the state, with 1,801 new cases.[246] These findings lead to the shutdown of plants with outbreaks with positive-testing individuals isolated at nearby hotels.[248]

May 18: Texas enters Phase 2 of the governor's reopening plan, allowing more businesses to open or increase their active capacity. The reopening phase also allows some businesses to open promptly;[249] these businesses include child care centers, gyms and exercise facilities, manufacturers, massage establishments, office buildings, and youth clubs.[250] Restaurants are allowed to begin operating at 50 percent capacity on May 29.[249] Other businesses and activities are also given staggered reopening dates under the reopening plan out to June 15.[250] Abbott delays the reopening timetables in Deaf Smith, El Paso, Moore, Potter, and Randall counties by one week.[251]

May 21: Texas Supreme Court Justice Debra Lehrmann tests positive for COVID-19, becoming the highest-ranking official with a reported positive test.[252] All active air travel restrictions for travelers arriving in Texas are lifted by Abbott, ending the mandatory 14-day self-quarantine requirement.[253] Abbott also announces a phased opening of driver license offices beginning in early June following their closure in March.[254] The HHSC expands COVID-19 testing to all patients and personnel at its 23 psychiatric hospitals and living centers; at that point, there were 161 positive cases at those facilities with at least one case at seven facilities.[138] CVS Pharmacy introduces COVID-19 testing at 44 locations in the state.[255]

May 22: Abbott issues an executive order to prohibit in-person visitation at all county and municipal jails in the state with the exception of meetings with attorneys or clergy.[256]

May 31: The DSHS reports 1,949 new cases of COVID-19, marking the highest daily total for May and setting a new record for highest daily case total since the beginning of the pandemic in Texas.[1]

June

June 3: Texas enters Phase 3 of Abbott's reopening plan, allowing most businesses to increase maximum occupancy to 50 percent. Restaurants are permitted to operate at 75 percent capacity beginning June 21 while outdoor college sports are allowed to resume immediately for the first time.[257]

June 8: The DSHS reports 1,935 active COVID-19 hospitalizations, marking the highest number since May 5.[258] TDEM begins to increase COVID-19 testing sites in minority communities disproportionately affected by the pandemic in Abilene, El Paso, Houston, Laredo, San Antonio, the Midland-Odessa metropolitan area, the Rio Grande Valley, and the Texas Coastal Bend. Testing is also increased in cities with large protests responding to the death of George Floyd.[259]

June 9: COVID-19 hospitalizations in the state reach record-highs for the second consecutive day, with 2,153 in total hospitalized on June 9 representing a 42 percent increase in hospitalizations since Memorial Day.[260] The DSHS attributes the increase in part to outbreaks at state prisons and meatpacking plants.[261]

June 16: The mayors of Arlington, Austin, Dallas, El Paso, Grand Prairie, Fort Worth, Plano, Houston, and San Antonio petition Abbott to allow local officials to mandate masks, stating that "a one-size-fits-all approach is not the best health policy" in a letter to Abbott.[262][263] Increasing hospitalizations prompt the city of Austin and Travis County to prolong stay-at-home orders by a month.[264]

June 19: The cumulative number of confirmed cases in Texas reported by the DSHS surpasses 100,000.[1] A new record for COVID-19 hospitalizations, with 2,947 people, is set for the seventh consecutive day.[265]

June 23: The state reports more than 5,000 new cases of COVID-19 in a single day for the first time, documenting 5,489. Hospitalizations related to COVID-19 also reach a record high with 4,092.[266] Abbott gives approval for mayors and county judges to enact restrictions on outdoor gatherings with more than 100 people, reducing the size limit from 500. Abbott also indicates that respirator enforcement is within the purview of local officials.[267] Abbott orders the HHSC to reinstate COVID-19 health and safety standards at child care centers, reversing the agency's lifting of those requirements on June 12.[268][269]

June 24: The seven-day average positivity rate—the ratio of positive cases of COVID-19 to tests conducted—rises above 10 percent, reaching levels unseen since mid-April and reaching a threshold Abbott referred to as a "red flag" in early May.[270][271] Connecticut, New Jersey, and New York announce a "joint travel advisory" mandating quarantines for travelers arriving from Texas and seven other states.[272] The TDEM and Texas Military Department begins distributing 3-ply masks freely to people testing at state-run mobile testing sites.[273]

June 25: A record-high number of new COVID-19 cases, 5,996, is set for the third consecutive day in Texas; the three days contribute over 17,000 cases to the cumulative case count.[274][275] The Texas Medical Center, the largest medical center in the world, reports 100 percent occupancy of its standard intensive care unit capacity, forcing the center to begin utilizing auxiliary "surge capacity".[276] Abbott suspends the reopening of the businesses in the state as hospitalizations and new COVID-19 cases begin to quickly rise, though prior relaxations of COVID-19 restrictions remain in place.[277][278] Elective medical procedures are banned by the governor in Bexar, Dallas, Harris, and Travis Counties to reduce pressure on hospital capacity.[278]

June 26: Abbott begins rolling back some of the lifted restrictions from his earlier state reopening plan, issuing an executive order that promptly closes bars and rafting and tubing businesses in addition to restricting indoor dining at restaurants to 50 percent capacity. The order also requires most outdoor gatherings with at least 100 people to seek approval by local governments.[279] Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo evaluates the county as having reached the highest threat level, indicating a "severe and uncontrolled level of COVID-19", and calls for the reinstatement of a stay-at-home order for the county in addition to prohibiting outdoor gatherings with more than 100 people in unincorporated parts of the county.[280][281][282] Tarrant County begins mandating face masks at all businesses.[283]

June 27: Austin Mayor Adler reports that the Greater Austin metropolitan area has the highest positivity rate for COVID-19 tests of any metropolitan area in the U.S. over the preceding week.[284] San Antonio sends an emergency alert urging residents in San Antonio and Bexar County to stay home after the city reports a record 795 new cases of COVID-19.[285]

June 29: Texas Medical Center (TMC) hospitals revised their calculation of ICU bed capacity, including other TMC hospital beds that can be converted into ICU beds and reassigning staff and equipment. This reduced TMC's total ICU usage on Sunday from 93% to 72%.[286] TMC provided an overview of their current ICU bed usage and capacity.[287]

June 30: The DSHS reports 6,975 new cases of COVID-19, marking the highest daily total for June and setting a new record for the highest daily case total since the beginning of the pandemic in Texas.[1] Abbott extends bans on elective medical procedures to Cameron, Hidalgo, Nueces, and Webb counties.[288] The Harris County Commission votes to extend the county's COVID-19 disaster declaration, which includes mandatory mask usage, to August 26.[289]

July

July 1: The DSHS records record-high cases and hospitalizations for the second consecutive day. The new cases are predominantly among younger cohorts and outbreaks at child care facilities.[290] Austin City Limits, one of the largest annual music festivals in the U.S., is canceled.[291]

July 2: Abbott mandates the wearing of face coverings in public spaces through an executive order, stating that it is "one of the most effective ways we have to slow the spread of COVID-19."[292] The order also stipulates a written and oral warning for first-time violations of the mask mandate and fines of up to $250 for each subsequent violation. Counties with 20 or fewer active cases of COVID-19 are allowed to opt-out of the order.[293] Children younger than 10 years old, people with an interfering medical condition are exempted from the order, as well as people attending church, voting at polling places, or exercising outdoors.[293][294] Austin Mayor Adler issues an executive order, restricting gatherings with more than 10 people outside of child-care services, religious gatherings, and recreational sports.[295]

July 4: The state sets a record for new COVID-19 cases in a single day, with 8,258, and a record for active COVID-19 hospitalizations, with 7,890; the latter represents the sixth consecutive day of increasing hospitalizations statewide.[296] Parks and beaches throughout the state remain closed for the Independence Day weekend.[297][298][299]

July 6: Fifty staff and parishioners at the Calvary Chapel in Universal City tested positive for COVID-19 after weeks of holding services while following “the letter of the law” about reopening. Pastor Ron Arbaugh, who tested positive along with his wife, took responsibility for allowing parishioners to hug inside the church.[300]

July 7: Over 10,000 new cases of COVID-19 are confirmed for the first time, surpassing the previous record set on July 4. The day ends with a record-high number of hospitalizations for the tenth-straight day, with 9,268 COVID-19 hospitalizations. The DSHS also reports the largest single-day increase in COVID-19 fatalities with 60, breaking a record set on May 14.[301][302] The State Fair of Texas, typically scheduled for the fall, is canceled for the first time since World War II.[303]

July 8: Recorded daily fatalities increased to a new high of 98, from the previous day's record of 60. Current infection rates will produce daily fatalities from 200 to 300 in about two weeks (if the growth will not accelerate more).[citation needed]

July 9: Number of recorded daily fatalities rises above 100 for the first time.

July 13: Number of new case continues to rise rapidly. The severity is expected to maintain in the Central, South and West counties while cooling off in the North. Averaged new case per day in Dallas expects to rise an extra 116 in two weeks after July 13.[304]

July 15: Texas set a record for new cases statewide reaching 10,975 new cases on July 15; this contributed to 289,837 total cases in Texas, including 105 deaths, with numbers in the nation's fourth largest city, Houston, reaching 32,695, including 304 deaths.[305] While being the "largest concentration" of people in Texas, Houston and Harris county in total are keeping an average number of infection and fatalities per capita.

July 17: 14,916 new infection cases and 174 covid-related fatalities are added. Total number of recorded infection cases has grown above 300,000. Accumulation of cases from 200,000 to 300,000 cases took 10 days. Previous 100,000 added cases took place over 17 days.

July 19: Governor Abbott announces that five United States Navy teams would be deployed to hospitals in Harlingen, Del Rio, Eagle Pass, and Rio Grande City. In the Rio Grande Valley, ambulance operators attempting to deliver patients to emergency rooms reported waiting up to ten hours.[306]

July 20: Texas comptroller predicts $4.6 billion budget shortfall due to coronavirus.[307]

July 22: A new highest fatalities per day, with 197 deaths reported; The Department of State Health Services also reported 9,879 new cases in Texas.[308]

July 24: Data including numbers culled from Texas Department of State Health Services by The Texas Tribune marked 10,036 hospitalized with confirmed COVID-19 diagnoses and 369,826 reported cases in 250 counties.[309]

July 25: For the fourth day, Texas continues to lead in the number of Covid-deaths among US states. Also, its 1,020 reported deaths in a week (1/6 of the US number) is higher than 882 in Florida, 652 in California or 67 in New York.[citation needed]

July 27: On this date, deaths in Texas spiked do to an "automation" error, reported on multiple news outlets. This is a striking statistical anomaly.[310][1]

July 29: The officially recorded number of daily fatalities became higher than 300 for the first time (313), while the total number of covid-assigned death cases passed 6,000 and the total number of detected infections exceeded 400,000. However, none of these claims are properly sourced directly from the CDC or the DSHS. Congressional Representative Louie Gohmert (R) from Texas, who is opposed to wearing masks, became infected.

August

August 3: The first date since the death rate has been tracked where Texas DSHS "reported" zero COVID-19 Assigned fatalities, because at this day it did not provide a report as informed in advance

August 11: Texas became the third state in the U.S. after California and Florida to exceed 500,000 in total number of reported cases.[311] Texas arrived to a very high (>20%) positivity rate on testing, this means virtually uncontrolled infection spreading. The high positivity and case fatality rates are an indicators of early "unexpected" infection appearance or an undeveloped country.

August 12: A new highest daily fatality report, 322, from Texas DSHS.

Responses

State responses

Testing

As of July 11, 2020[update], 2.7 million COVID-19 tests have been reported by the DSHS; of these, 2.49 million were viral tests while 217,000 were antibody tests. The total number of tests passed 100,000 on April 9 and passed 1 million on May 28, 2020.[312] In mid-February, the DSHS provided outlines of coronavirus patient protocols to medical facilities statewide. Possible cases were to be reported to local health departments, with potential viral samples to be sent to the CDC in Atlanta.[313] The agency also prepared laboratories to test for the virus within Texas using kits provided by the CDC.[314][315] The DSHS and TDEM initiated bi-weekly emergency planning meetings with other state agencies after February 27.[314] A laboratory at Texas Tech University in Lubbock became the first laboratory to test for SARS-CoV-2 in Texas.[316] By March 5, six of the ten health labs comprising the state Laboratory Response Network were ready for COVID-19 testing.[317] The Texas National Guard began supporting testing efforts on March 27.[173]

Initial actions and first lockdown

In March 2020, The Texas Tribune described the state's pandemic response as a "patchwork system" characterized by its decentralized nature and reliance on locally enacted policies.[318] The following month, WalletHub ranked the Texas as one of the 10 least aggressive states for limiting COVID-19 exposure based on policy decisions, risk factors, and infrastructure.[319]

The DSHS activated a virtual State Medical Operations Center (SMOC) in January 2020 to coordinate data collection and activities between the state and local agencies. The department and local health departments also began assessing recent travelers to Hubei Province in China with respiratory ailments for possible testing for SARS-CoV-2, encouraging individuals to "contact their health care provider if they develop fever, cough or shortness of breath within 14 days of being in Hubei." The Texas Division of Emergency Management (TDEM) was tasked with logistical coordination on health supplies with local groups. A briefing was held by Abbott on January 27 concerning the COVID-19 outbreak; HHS Commissioner Courtney Philips, DSHS Health Services Commissioner John William Hellerstedt, and TDEM Chief Nim Kidd delivered the briefing.[320] On January 30, Abbott joined other state governors in a conference call with U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, CDC Director Robert Redfield, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Anthony Fauci, and other health officials to discuss disease mitigation and prevention strategies.[321] State officials from emergency management, heath services, law enforcement, public schools, and universities also met the same morning to outline logistics and coronavirus information.[37]

A state of disaster was declared by Abbott for all counties in Texas on March 13, giving emergency powers to Abbott and his administration to order lockdowns.[108][109] Throughout March, the state waived various healthcare and economic regulations.[322] These included waived trucking and licensing regulations for drivers, alcohol delivery from bars and restaurants, and Medicaid regulations.[109][323][324][325] Abbott and the Texas Department of Insurance (TDI) requested health insurers and health maintenance organizations to waive pandemic-related costs for patients on March 5.[326] The Texas Supreme Court ruled to suspend most eviction proceedings by at least a month on March 19.[143] Several regulations were waived to increase the state's medical workforce;[327][328][177] inactive and retired nurses were allowed to reactivate their licenses and temporary licensing was expedited for out-of-state medical professionals.[153][329] Local governments were authorized to delay local elections for 2020.[134] The federal government supplied $628.8 million in public assistance grants to Texas through FEMA following a federal disaster declaration on March 25.[170] Additional federal funding was also distributed through the CARES Act, Small Business Administration,[162][128]

On March 19, Abbott ordered the temporary prohibition of dining at bars and restaurants and the closure of gyms effective beginning the following day in a series of executive orders. Social gatherings involving more than 10 people were also prohibited.[142][330] Two days later, hospitals were allowed to have more than one patient per room and "elective or non-essential" medical procedures were ordered suspended.[155] A legal dispute emerged after Attorney General Ken Paxton confirmed that most abortions were included in the suspension.[156][157][331] The United States District Court for the Western District of Texas blocked the abortion ban on March 30, which was overturned by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on March 31.[159][158] A three-judge panel on the Fifth Circuit reaffirmed the ban on April 10.[332] Texas became the 21st state to activate its National Guard on March 17.[125] The state mandated 14-day quarantines for travelers arriving from pandemic hotspots in the U.S. beginning on March 26 until all travel restrictions were lifted on May 21.[171][253] Abbott initially decided against statewide shelter-in-place or stay-at-home orders due to the fact that more than 200 counties did not have any cases in mid-March.[333][334] However, Abbott issued a de facto stay-at-home order on May 31 directing all Texans to remain at home unless conducting essential activities and services and to "minimize social gatherings and minimize in-person contact with people who are not in the same household." The order exempted places of worship as essential services (subject to social distancing), but Abbott still recommended that remote services be conducted instead. Abbott specifically avoided use of the terms "stay-at-home order" or "shelter-in-place" to describe the order, arguing that they were either misnomers (shelter-in-place usually referred to emergency situations) or did not adequately reflect the goal of the order.[335][336]

Texas Historical Commission historical sites and state parks were closed beginning at 5 p.m. April 7,[197][337] remaining closed until an executive order reopened them on April 20.[338][339] The state government continued to relax regulations regarding medical protocols through April. Pharmacy technicians were authorized to accept over-the-phone prescription drug orders beginning on April 7 and telehealth services were authorized across a broad range of telecommunication media.[340][341] Local emergency medical service providers were allowed to utilize qualified individuals without formal certification.[342] Similar training requirements were waived for other medical fields.[343][344] On May 20, The Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Speaker of the House released a letter detailing a plan to reduce the budget of many state agencies by 5 percent as part of the state's preparation for COVID-19's economic impact.[345][346]

Reopening efforts

Between May and June 2020, the Texas state government began loosening restrictions on businesses and activities in a series of phases amid the pandemic, allowing businesses to reopen and operate with increasing capacity.[347] Texas was one of the first states to publicize a timetable for lifting restrictions and the underlying plan was one of the most expansive in the country for reopening businesses.[348][349] It began with Phase I on May 1 and continued through Phase III on June 3. Abbott suspended the reopening process on June 25 following a rapid increase of COVID-19 cases 113 days after the first case was confirmed in Texas.[347]

On March 23, Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick made controversial statements on the Fox News show Tucker Carlson Tonight, saying that "as a senior citizen", he was "willing to take a chance on [his] survival in exchange for keeping the America that all America loves for [his] children and grandchildren," later suggesting that grandparents in the country would do the same and advocating that the U.S. "get back to work."[350][351] As Patrick appeared to insinuate lives were worth sacrificing for the health of the economy, his comments drew criticism on Twitter, where the hashtag #NotDying4WallStreet trended.[352] New York Governor Andrew Cuomo commented on Twitter that "no one should be talking about social darwinism for the sake of the stock market."[353] The editorial board of the Fort Worth Star-Telegram characterized Patrick's comments as "morbid" and a "recipe for embarrassing Texas".[354] On April 7, roughly a month after the first non-evacuee case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Texas,[66] Patrick created a task force to plan out the recovery of the Texas economy should businesses and industries reopen.[199] Two days later, Abbott stated that his administration was "working on very aggressive strategies to make sure Texas [was] first at getting back to work."[355] On April 17, Abbott began the process of reopening the Texas economy,[356] establishing the Strike Force To Open Texas in an executive order to "study and make recommendations... for revitalizing the Texas economy".[338][357] The team includes state leaders, medical experts, and a business advisory group; all consulting members were members of the Republican Party.[214][215] Abbott issued two additional executive orders relaxing COVID-19 restrictions: executive order GA-15 permitted licensed health care professionals and facilities to carry out elective medical procedures if they did not interfere with capacity provisioned for COVID-19, while executive order GA-16 allowed retail stores to deliver goods to customers beginning on April 24 as part of a "Retail-To-Go" model.[338][358][359] State parks were also ordered to reopen with COVID-19 regulations on April 20.[338]

Abbott announced a phased approach to reopening the Texas economy on April 27, with the state entering Phase I of the plan on May 1.[360] The first phase permitted the operation of retail establishments, restaurants, movie theaters, shopping malls, libraries and museums at 25 percent occupancy and with health protocols in place; these relaxed restrictions superseded all local orders.[361][362] Businesses in counties with five or fewer cases of COVID-19 were allowed to operate with increased occupancy once Phase I went into effect.[363] The de facto statewide stay-at-home order issued on March 19 was allowed to expire on April 30.[364] Following intraparty pressure, Abbott authorized the reopening of hair salons and pools on May 5.[365] Abbott announced the initiation of Phase II of the reopening plan on May 18, under which child care centers, massage and personal-care centers, and youth clubs were allowed to open promptly. The phase also allowed bars and office building tenants to begin operating with limited occupancy in addition to raising the restaurant occupancy cap to 50 percent. Other types of businesses were given staggered opening dates out to May 31 under Phase II.[366] Phase III of the reopening was rolled out on June 3, permitting the immediate increase of all business operation to 50 percent capacity. The phase also provided a timetable for amusement parks, carnivals, and restaurants to begin increasing their capacity further out to June 18.[367] Abbott announced on June 18 that Texas public schools would be opening for fall 2020.[368] On June 25, Abbott enacted a "temporary pause" on the reopening of the state's economy following record increases in COVID-19 cases.[369][370] The next day, Abbott issued an executive order closing bars and rafting/tubing businesses, representing the first rollbacks on the reopening plan.[279]

On April 25, polling from the University of Texas and the Texas Tribune found that 56 percent of voters surveyed approved of Abbott's response to the pandemic, including 56 percent of Republicans and 30 percent of Democrats.[371][372] Positive approval of Abbott's response to the pandemic was also found by a Dallas Morning News/University of Texas at Tyler poll, with registered voters approving by a roughly 3-to-1 margin.[373] A survey conducted by the Texas Restaurant Association and released on May 2 found that 47 percent of the 401 responding restaurants stated they would not reopen despite authorization under Phase I of Abbott's reopening plan; 43 percent intended to open while the remaining 9 percent were unsure.[374] A Quinnipiac University poll of registered voters released on June 3 found that 49 percent approved of Abbott's handling of stay-home restrictions while 38 percent believed Abbott moved "too fast" with the reopening.[375] A survey of 1,212 registered voters in Texas conducted by YouGov and sponsored by CBS News between July 7–10 found that 61 percent of respondents believed the state moved "too quickly" in "reopening the economy and lifting stay-at-home restrictions".[376]

Reactions to the initial efforts to reopen Texas businesses were fraught with partisan divides,[377][378] with the overall reaction described as "mixed" by several news agencies.[379][380][381][382] Nine members of the Texas Freedom Caucus in the Texas House of Representatives sent a letter to Abbott on April 14 pressing for business restrictions to be loosened "to the greatest extent possible."[383] Following the first announcement of reopenings on April 17, Texas Representative Chris Turner, the leader of the Texas House Democratic Caucus, said that Texas needed to have "widespread testing available" before reopening businesses.[384] Many public health experts lauded the phased approach but iterated the need for increased testing in the state. Others opined that the reopening commenced before adequate steps were taken to reduce the spread of the disease.[380][385] As the reopening plan progressed, Republican legislators pressured Abbott to open additional business sectors and accelerate the reopening process while Democratic legislators criticized the governor for the rapid pace of reopening.[386][387] The lack of consistent policy at the state and local level during the reopening and Abbott's decision to quash criminal penalties for violations also drew criticism. The Texas District and County Attorneys Association stated that there was "little incentive to put your own necks on the line to enforce an order that could be invalidated the next day" in guidance to state prosecutors.[388] After the reopening's pause and subsequent roll back, some attributed the concurrent rise in cases to the reopening.[389] Hidalgo stated that the reopening occurred "too quickly" and that other communities seeking to reopen would need to heed the spike in cases as "a word of warning".[377] Abbott stated in an interview with KVIA-TV in El Paso that "If I could go back and redo anything, it would probably would have been to slow down to opening bars, now seeing in the aftermath of how quickly the coronavirus spread in the bar setting."[390]

June–July 2020 restrictions

At a news conference on May 5, Abbott indicated that his administration was emphasizing the state's COVID-19 positivity rate to evaluate the reopening of Texas businesses that formally began on May 1.[360][271] Abbott considered a positivity rate exceeding 10 percent as a "red flag". In mid-April, the number of new cases began to stabilize and the 7-day average positivity rate fell below 10 percent. When Abbott announced the reopening plan on April 27, the positive rate was 4.6 percent, while number of active cases, active infection spread among population, was growing, meaning the chance of infection was increasing. As a result, the number of new cases began to rise in early May.[271] On June 24, the seven-day average positive rate rose above 10 percent for the first time since mid-April.[270] Entering mid-June, restaurants were allowed to operate at increased capacity and most businesses were opened under Phase III of the state's reopening plan. Following a pronounced outbreak of COVID-19 in the state (with the weekly average of new cases increasing by 79 percent) and a large increase in hospitalizations, Abbott paused the reopening process on June 25.[391][279] On June 26, bars were ordered to shut down and restaurants were ordered to lower their maximum operating capacity to 50 percent in what The Texas Tribune called Abbott's "most drastic action yet to respond to the post-reopening coronavirus surge in Texas". River-rafting businesses were also ordered to close and outdoor gatherings of more than 100 people without local government approval were banned.[392] The mandated closures made Texas the first U.S. state to reinstate restrictions and closures after reopening.[393]

Only on July 2, when Texas had already recorded more than twice the infections in all of China, Abbott announced some small measures in an executive order effective the afternoon of July 3 requiring local government approval of gatherings of 10 or more people. In counties with at least 20 confirmed cases, the order mandated masks in enclosed public spaces and when social distancing was not feasible (subject to fines of up to $250 for multiple infractions).[394] The Texas Medical Association supported the mask mandate. However, the governor was chided by Democrats for being too slow to react to the resurgence in cases and by Republicans for overstepping his remit and infringing on personal freedoms.[395][293] Texas Democratic Party spokesman Abhi Rahman released a statement saying that the order was "far too little, far too late," and criticized Abbot for "[leading] from behind."[396] Republican State Representative Jonathan Stickland tweeted "[Abbott] thinks he is KING!"[293] Six county Republican parties formally censured Abbott for his use of executive power in responding to the pandemic, including in Montgomery and Denton Counties.[397] Some local law enforcement agencies chose not to enforce the mandate.[398]

Local responses

On March 2, San Antonio Mayor Ron Nirenberg and Bexar County both declared a "local state of disaster and a public health emergency" after an individual was mistakenly released from quarantine at Joint Base San Antonio by the CDC before a third test for coronavirus returned a positive result.[399] The city subsequently petitioned the federal government to extend the quarantine of US nationals at Joint Base San Antonio; the petition was denied by Judge Xavier Rodriguez in the United States District Court for the Western District of Texas.[400][401] Both the city of Dallas and Dallas County have declared a "local disaster of public health emergency".[402]

Abbott left the decision to local governments to set stricter guidelines. Two hours later, Dallas County Judge Clay Jenkins ordered residents of Dallas County to shelter in place beginning 11:59 p.m. on the following day.[403] A day later on March 23, Bell,[404] Bexar,[405] Brazos,[406] Cameron,[407] Hunt,[408] McLennan,[409] Stephens[410] counties and the city of Forney,[411] issued a shelter in place for their communities. Collin,[412] Galveston,[413] Harris,[414] Travis,[405][415] and Williamson[415] counties issued same measures on March 24. However, Collin County had more relaxed guidelines for their shelter in place order. Collin County's order stated that all businesses are essential and would be allowed to remain open as long as they followed physical distancing guidelines.[416]

Austin, TX's cancellation of the South by Southwest festival was met with response from bar owners on 6th St who boarded up their windows to avoid break-ins due to overstocking in preparation for SXSW, which had built up in popularity from 700 attendees in 1987 to more than to 280,000 attendees in 2019 and an economic impact on the Austin economy of $355.9 million.[417] Local artisans adorned the windows of the boarded up shops with street art that captured the mood of the time depicting both despair and declarations of ultimate triumph.[418]