Second Battle of Adobe Walls

| Second Battle of Adobe Walls | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Red River War | |||||||

Adobe Walls battlefield looking southeast from Billy Dixon's grave. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Comanche | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| N/A |

Isa-tai (Kwahdi Comanche) Quanah Parker (Nokoni Comanche) Kobay-oburra (Kwahadi Comanche) Pearua-akupakup (Nokoni Comanche) Mow-way (Kotsoteka Comanche) Tabananika (Yamparika Comanche) Isa-rosa (Yamparika Comanche) Hitetetsi aka Tuwikaa-tiesuat (Yamparika Comanche) Guipago (Kiowa) Satanta (Kiowa) Tsen-tainte (Kiowa) Zepko-ete (Kiowa) Little Robe (Cheyenne) White Shield (Cheyenne)[1]: 208 | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 28 hunters and tradesmen | ~700 warriors[1]: 208 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 4 killed, unknown wounded | unknown killed, unknown wounded. 15 bodies lay too close to the walls to be recovered + 1 killed long range | ||||||

Location within Texas | |||||||

The Second Battle of Adobe Walls was fought on June 27, 1874, between Comanche forces and a group of 28 U.S. bison hunters defending the settlement of Adobe Walls, in what is now Hutchinson County, Texas. "Adobe Walls was scarcely more than a lone island in the vast sea of the Great Plains, a solitary refuge uncharted and practically unknown."[1]: 225

Background

Adobe Walls settlement

Adobe Walls was the name of a trading post in the Texas Panhandle, just north of the Canadian River. In 1845 an adobe fort was built there to house the post, but it was blown up by traders three years later after repeated Indian attacks. In 1864 the ruins were the site of one of the largest battles ever to take place on the Great Plains. Colonel Christopher "Kit" Carson led 335 soldiers from New Mexico and 72 Ute and Jicarilla Apache scouts against a force of more than 1000 Comanche, Kiowa and Plains Apache. The Indians forced Carson to retreat, though he was acclaimed as a hero for successfully striking a blow against the Indians and for leading his men out of the trap with minimal casualties. This is known as the First Battle of Adobe Walls.

After the "enormous slaughter" of the buffalo in the north during 1872 and 1873, the hunters moved south and west "into the good buffalo country, somewhere on the Canadian . . . in hostile Indian country".[1]: 145 and 153 In June 1874 (ten years after the first battle) a group of enterprising businessmen had set up two stores near the ruins of the old trading post in an effort to rekindle the town of Adobe Walls. The complex quickly grew to include a store and corral (Leonard & Meyers), a sod saloon owned by James Hanrahan, a blacksmith shop (Tom O'Keefe) and a sod store used to purchase buffalo hides (Rath & Wright, operated by Langton),[1]: 176 and 178 all of which served the population of 200-300 buffalo hunters in the area. By late June "two hunters had been killed by Indians twenty-five miles down river, on Chicken Creek" and two more were killed in a camp on "a tributary of the Salt Fork of Red River" north of present-day Clarendon.[1]: 186 "The story of the Indian depredations had spread to all the hunting camps, and a large crowd had gathered in from the surrounding country" at the "Walls".[1]: 192–193

American Indian alliance

The remaining free-ranging Southern Plains bands (Comanche, Cheyenne, Kiowa and Arapaho) perceived the post and the buffalo hunting as a major threat to their existence. That spring the Indians held a sun dance. Comanche medicine man Isatai'i promised victory and immunity from bullets to warriors who took the fight to the enemy.[1]: 210 The 1867 Medicine Lodge Treaty reserved the area between the Arkansas River and Canadian River as Indian hunting grounds. Yet, since 1873, several buffalo hunting parties operated in the area, in violation of the treaty, prompting Indian outrage.[2]

Battle and siege

On June 5, 1874, Hanrahan and his party of hunters departed Dodge City for Adobe Walls. The party encountered a band of Cheyenne Indians on June 7 at Sharp's Creek, 75 miles southwest of Dodge, who ran off all of their cattle. The party then joined a wagon train that was en route to the Walls, arriving just hours before the major battle took place. Some 28 men were then present at Adobe Walls, including James Hanrahan (the saloon owner), 20-year-old Bat Masterson, William "Billy" Dixon (whose famous long-distance rifle shot effectively ended the siege) and one woman, the wife of cook William Olds.[1]: 200

At 2:00 am on June 27, 1874, the ridgepole holding up the sod roof of the saloon made a loud cracking sound, although two men nearby thought that it sounded like "the report of a rifle".[1]: 201 and 241 According to some sources Hanrahan awoke the camp by firing a gun, then telling the others that the sound had come from the ridgepole. The reason for his action was that he knew about the attack in advance, but did not tell anyone, afraid that men would leave the camp, hurting his business.[3] Everyone in the saloon and several other men from the town immediately set to repair the damage. Thus, most of the inhabitants were already wide awake and up at dawn when a combined force of Comanche, Cheyenne and Kiowa warriors swept across the plains, intent on erasing the populace of Adobe Walls. In Dixon's words:

There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight. In after years I was glad that I had seen it. Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern Plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind. Over all was splashed the rich colors of red, vermillion and ochre, on the bodies of the men, on the bodies of the running horses. Scalps dangled from bridles, gorgeous war-bonnets fluttered their plumes, bright feathers dangled from the tails and manes of the horses, and the bronzed, halfnaked bodies of the riders glittered with ornaments of silver and brass. Behind this headlong charging host stretched the Plains, on whose horizon the rising sun was lifting its morning fires. The warriors seemed to emerge from this glowing background.[1]: 205

The Indian force was estimated to be in excess of 700 strong[1]: 208 and led by Isatai'i and Comanche Chief Quanah Parker, son of a captured white woman, Cynthia Ann Parker. Their initial attack almost carried the day; the Indians were in close enough to pound on the doors and windows of the buildings with their rifle butts. The fight was in such close quarters that the hunters' long-range rifles were useless. They were fighting with pistols and Henry and Winchester lever-action rifles in .44 rimfire. After the initial attack was repulsed, the hunters were able to keep the Indians at bay with their large-caliber, long-range Sharps rifles. Nine men were located in Hanrahan's Saloon—including Bat Masterson and Billy Dixon—11 in Meyer's & Leonard's Store and seven in Rath & Wright's Store.[1]: 207

The hunters suffered four fatalities, three on the first day: the two Shadler brothers asleep in a wagon[1]: 208 were killed in the initial onslaught, and Billy Tyler was shot through the lungs as he entered the doorway of a building while retreating from the stockade.[1]: 212 On the fifth day William Olds accidentally shot himself in the head while descending a ladder at Rath's store.[1]: 235 A search following the initial battle turned up the bodies of 15 Indians killed so close to the buildings that their bodies could not be retrieved by their fellow warriors.

"By noon the Indians had ceased charging, and had stationed themselves in groups in different places, maintaining a more or less steady fire all day on the buildings", by 2 pm the Indians rode out of range at the foot of the hills, and by 4 pm the besieged started venturing out from the buildings to gather relics and bury the Shadlers.[1]: 213, 219, 221 and 227 The Indians stayed in the distance while deciding how to handle the situation, effectively laying siege to Adobe Walls.

During the second day the besieged buried or dragged away the dead horses to "prevent the evil smell from reaching the buildings".[1]: 230 George Bellfield's outfit made it to the Walls, as did Jim and Bob Cator, while Henry Lease volunteered to ride to Dodge City, Kansas, while two hunters visited the surrounding camps to warn them that "the Indians were on the war path".[1]: 231 and 233

On the third day after the initial attack, 15 Indian warriors rode out on a bluff nearly a mile away to survey the situation. At the behest of one of the hunters, William "Billy" Dixon, already renowned as a crack shot, took aim with a "Big Fifty" Sharps (it was either a .50-70 or -90, probably the latter) that he had borrowed from Hanrahan and cleanly dropped a warrior from atop his horse. "I was admittedly a good marksman, yet this was what might be called a 'scratch' shot."[1]: 233 Seeing their fellow warrior killed from such a distance apparently so discouraged the Indians that they decamped and gave up the fight.

More hunters came in on the third and subsequent days so that, by the sixth day, the garrison amounted to about 100 men.[1]: 234 Those in the camp might have experienced it as a siege, although sieges were not part of Comanche warfare or battle strategy. Nevertheless, Indians were close by during the days after the initial attack. Quanah had been wounded,[1]: 240 which might have taken the edge off the attack, as was always the case with Comanches when the war chief fell in battle.[3] The Indians retired soon afterward. "The Indians probably came to the conclusion that if they remained long enough, charged often enough and got close enough, all of them would be killed, as they were unable to dislodge us from the buildings."[1]: 239 Casualty reports vary, and are not known with any great accuracy, although most agree that fewer than 30 total deaths would be a close number.

Within a week of the fight, 25 men headed to Dodge, including Hanharan, Masterson and Dixon, only to learn upon arrival that a relief party of 40 men under Tom Nixon had already headed south to bring back "Mrs. Olds and the greater part of the men".[1]: 244 and 247

By August a troop of cavalry made it to Adobe Walls, under Lt. Frank D. Baldwin, with Masterson and Dixon as scouts, where a dozen men were still holed up.[1]: 247 "Some mischievous fellow had stuck an Indian's skull on each post of the corral gate."[1]: 248 The killing had not ended, however; one civilian was lanced by Indians while looking for wild plums along the Canadian River.[1]: 249 The next day the soldiers and remaining men left Adobe Walls, heading south to join Gen. Nelson A. Miles' main command on Cantonement Creek.[1]: 250 The Indians later "burned the place to the ground."[1]: 251

Billy Dixon's lucky shot

Controversy prevails over the exact range of Billy Dixon's shot. Baker and Harrison set it at about 1000 yards, while a post-battle survey by a team of US Army surveyors, under the command of Gen. Nelson A. Miles, measured the distance: 1,538 yards, or nine-tenths of a mile. For the rest of his life, Billy Dixon never claimed that the shot was anything other than a lucky one; his memoirs do not devote even a full paragraph to "the shot".[4] He, however, did confide to people in the area that he took to the shot near an outcropping of rock that the hunters regularly shot from their camp in a betting game. In addition, he spoke about the incident that made him shoot at the Indians on the hilltop.[5]

Forensic archaeologists have discovered that the guns in use at Adobe Walls included several Richards' Colt conversions, some Smith & Wesson Americans and at least one Colt .45 (then new on the frontier) pistol, along with numerous rifles in calibers .50-70, .50-90, .44-77, .44 Henry Flat and at least one .45-70 (also very new). At the time Sharps did not use designations like .50-90 ("Big Fifty" Sharps). Instead, it designated cartridges by bore size and case length. Technically, the "Big Fifty" was known as the .50 Sharps 2-1/2 Inch. Depending on the bullet used, the case could be loaded as any of what was later designated .50-90, .50-100 or .50-110. The .50-90 loading used the heaviest bullet and gave the best performance at relatively short ranges out to about 100 yards. The two heavier loads used relatively lighter bullets and gave better performance at extended ranges. This makes it more likely that Billy Dixon's shot was made with a .50 Sharps 2-1/2 Inch case loaded to .50-110 specification. In Sharps' nomenclature, the .50-70 was first known as the .50 Sharps 1-3/4 Inch and later as the .50 Sharps 2 Inch, and was sometimes referred to as the "Little Fifty."

Aftermath

Buffalo hunting ended in that region of the country "just as the Indians had planned".[1]: 241 The result of Adobe Walls was a crushing spiritual defeat for the Indians, though it was seen as a military victory. It also prompted the U.S. military to take its final actions to crush the Indians once and for all. Within the year the long war between whites and Indians in Texas would reach its conclusion.

In September, just three months after Adobe Walls, an army dispatch detail consisting of Billy Dixon, another scout (Amos Chapman) and four troopers from the 6th Cavalry were surrounded and besieged by a large combined band of Kiowas and Comanches. During what became known as the Battle of Buffalo Wallow, with accurate rifle fire they held off the Indians for an entire day. An extremely cold rainstorm that night discouraged the Indians, and they broke off the fight; every man in the detail was wounded and one trooper killed. For this action Billy Dixon, along with the other survivors of "The Buffalo Wallow Fight", were awarded the Medal of Honor.

Significance

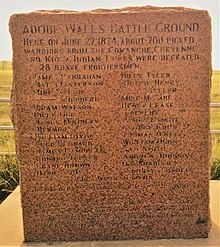

This fight is historically significant because it led to the Red River War of 1874–75, resulting in the final relocation of the Southern Plains Indians to reservations in what is now Oklahoma. A monument was erected in 1924 on the site of Adobe Walls by the Panhandle-Plains Historical Society.

On June 27, 1924, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the second Battle of Adobe Walls was held at the site in Hutchinson County. A marble shaft bearing the names of those who took part in the battle was unveiled. W.T. Coble and his wife, the owners of the Turkey Track Ranch on which the site is located, deeded five acres of land to the Panhandle Plains Historical Society in Canyon, Texas, for the permanent preservation of the historic spot. The society subsequently founded the Panhandle Plains Historical Museum.[6]

There is an exhibit of the battle in the Hutchinson County Historical Museum in Borger.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad Dixon, O., Life and Adventures of "Billy" Dixon, 1914, Guthrie: Co-operative Publishing Company

- ^ Holden, W.C. (1962). Graves, Lawrence (ed.). Indians, Spaniards, and Anglos, in A History of Lubbock. Lubbock: West Texas Museum Association. pp. 32–33.

- ^ a b "Empire of the summer moon", S.C. Gwynne, 2010, ISBN 1416591060

- ^ Coyote Creek, Mike. "History of Adobe Walls". San Jose, CA: Faultline Shootist Society. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05.

- ^ In 1994, I met J.B, Buchanan while living in Spearman, Texas. At that time he was 88 years old, born 1906, we became good friends while I was working to obtain his collection of Windmills for the eventual J.B. Buchanan Windmill Park in Spearman Texas (http://www.spearman.org/page5.html) as a member of the Historical Society. J.B. was still very alert and clear minded at the time of our mutual meetings. He was born and raised in the area. His father told him about knowing Billy Dixon as postmaster in Stinnett, Texas. The men used to gather at the post office, swap stories and drink coffee, especially during the winter. People were always fascinated with the story of the 2nd Battle of Adobe Walls and would ask Billy about it. He told them that because they had almost unlimited ammunition they used to sit at their campfire and shoot at an outcropping of rock. If the shooter hit the rock face, it would make a white puff that could be seen in the camp. It became a betting game. When the Indian warriors were standing on the ridge, they were standing just above the rock outcropping. So he had practiced a similar shot many times before. One day the men were badgering Billy and asking him why he ever took the shot when he finally responded to the question, "Billy, Why did you shot that Indian?" To which he responded, "Because he was shaking his ass at us." Apparently, the Indians were taunting the buffalo hunters and it made Billy mad. He then lifted his rifle, repeating a long practiced shot and aimed slightly higher. Personal interview notes of J. B. Buchanan by Kyle Henderson, PHD. of the Hansford County Historical Society, 1996.

- ^ Lester Fields Sheffy, The Life and Times of Timothy Dwight Hobart, 1855-1935: Colonization of West Texas (Panhandle-Plains Historical Society, 1950), pp. 282.

- Rupert N. Richardson, "The Comanche Indians at the Adobe Walls Fight", Panhandle-Plains Historical Review 4 (1931).

- G. Derek West, "The Battle of Adobe Walls", Panhandle-Plains Historical Review 36 (1963).

- T. Lindsay Baker and Billy R. Harrison, Adobe Walls: The History and Archaeology of the 1874 Trading Post College Station: Texas A&M University Press (April 4, 1986), trade paperback, 452 pages, ISBN 978-1-58544-176-1

Further reading

- Little, Edward Campbell (January 1908). "The Battle of Adobe Walls". Pearson's Magazine: 75–85. Retrieved 2009-07-08.

External links

- The Battle of Adobe Walls, Texas State Library