A Boyar Wedding Feast

| A Boyar Wedding Feast | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Konstantin Makovsky |

| Year | 1883 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 240 cm × 390 cm (94 in × 150 in) |

| Location | Hillwood Museum, Washington, D.C. |

A Boyar Wedding Feast[nb 1] was painted in 1883 by Russian artist Konstantin Makovsky (1839–1915).[nb 2] The painting shows a toast at a wedding feast following a boyar marriage, where the bride and the groom are expected to kiss each other. The bride looks sad and reluctant, while the elderly attendant standing behind her encourages the bride to kiss the groom. The work won a gold medal at the World's Fair held in Antwerp, Belgium in 1885,[2] and is considered to be one of Makovsky's most popular works.[6][8] It is currently located in Hillwood museum, Washington DC, US.[9]

Background[edit]

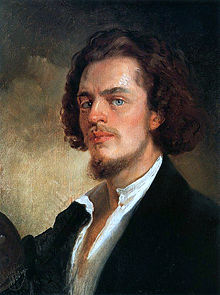

Konstantin Makovsky (1839–1915) was a famous Russian realist painter who opposed academic restrictions that existed in the art world at the time. His father was the Russian art figure and amateur painter, Egor Makovsky and his mother was a composer. Because of his parents' professions, Makovsky showed an early interest in painting and music. He entered the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture at the age of 12, where he was influenced by teachers such as Vasily Tropinin and Karl Bryullov. After graduating, Makovsky went to France in hopes of becoming a composer, but after touring Europe in order to get acquainted with traditional folk and classical music, he ultimately chose painting.[10][11]

In 1858 Makovsky entered the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, where he created artworks such as Curing of the Blind (1860) and Agents of the False Dmitry kill the son of Boris Godunov (1862). In 1863, Makovsky and thirteen other students protested against the Academy's decision to only allow artwork of Scandinavian mythology in the competition for the Large Gold Medal of Academia. Thus, all of them left the academy without a diploma. This incident later came to be known as the "Revolt of the Fourteen".[12][13][11]

Later, Makovsky joined the Artel of Artists, a cooperative association founded by Ivan Kramskoi, whose members were realist artists that advocated for more realistic depictions of the everyday life of old Russia. Notable works by Makovsky of this period are "The Widow" (1865) and "The Herringwoman" (1867). In 1870 he became a founding member of the Society for Travelling Art Exhibitions and continued to work on paintings in the realism genre. He went on to travel North Africa and Serbia in the mid-1870s., which resulted in a significant stylistic change as he started putting greater emphasis on colours and shapes.[11]

At the World's Fair of 1889 in Paris, he received the Large Gold Medal for his paintings Death of Ivan the Terrible, The Judgement of Paris, and Demon and Tamara. By the end of the century, Makovsky was one of the most respected and highly-paid Russian artists, regarded by some critics as the forerunner of Russian impressionism. He died in 1915 when his crew crashed into a tram on the streets of St. Petersburg.[12][11]

Painting[edit]

A Boyar Wedding Feast is an oil on canvas painting measuring 93 in × 154 in (240 cm × 390 cm), set in either the 16th[3] or 17th century,[2] in which a room of guests are depicted toasting a newlywed couple. A traditionally offered boyar wedding toast is meant to encourage the first kiss to make the wine sweeter.[14] The couple stands at the head of the table (right), where the groom presents his bride to the wedding guests[15] and sees her without her veil for the first time.[5] She appears timid and bashful as the men toast for the first kiss.[7] To the right of the couple, the "Lady of Ceremony" gently urges on the bride.[nb 3]

Makovsky's depiction of the wedding, an important social event of 16th and 17th century boyar life, is dramatically lit. The guests are depicted at the table with food and drink served on silverware in front of them. A roasted swan is being brought in on a large platter, the last dish served before the couple retire into the bedroom. Luxurious details such as silver cups, richly embroidered garments, and an ivory chest with a silver bowl in the foreground are depicted. The bride and the other women are wearing pearl-studded kokoshniki, a Russian woman's headdress.[17][18][19]

Provenance[edit]

Winning the 1885 medal of honor at the Exposition Universelle d'Anvers (2 May – 2 November 1885), A Boyar Wedding Feast was purchased by American jeweler and art collector Charles William Schumann in August 1885[20] for $15,000[21] (or £10,000).[3] Schumann reportedly outbid Alexander III of Russia to obtain the work.[2] The painting was auctioned as part of Schumann's estate on 23 January 1936 and sold for $2,500.[22] Sometime after the sale, A Boyar Wedding Feast entered the collection of Robert Ripley, creator of Ripley's Believe It or Not!.[23] It was sold during his estate sale on 26 August 1949 for $2,200.[24] The painting was again offered for sale on 18 December 1968.[25] Between 1968 and 1973, the painting was acquired by Marjorie Merriweather Post. Upon her death in 1973, the Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens was founded by Post's estate, and A Boyar Wedding Feast was donated to the collection.[9]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes

- ^ Variations of the painting’s title include: The Russian Wedding Feast,[1] A Russian Wedding Feast of the Seventeenth Century,[2] and The Wedding Fête of the Boyars in the Sixteenth Century[3]

- ^ Spelling variations of the artist's name include: Constantin Makovsky,[4] Makovski,[5] Makowski,[6] Makowsky,[3] and Constantine Makoffsky[7]

- ^ The Lady of Ceremony (usually an older relative appointed to be guardian for the wedding day) would advise the bride on traditional Boyar marriage practices.[16]

Citations

- ^ Coffin 1917, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d "Russian Art – Konstantin Makovsky", The Mentor, 5 (19), Mentor Association: 537, 1917

- ^ a b c d Fry & Goodwin 1999, p. 108.

- ^ Keyser 1904, p. 171.

- ^ a b Champlin & Perkins 1900, p. 415.

- ^ a b Slocum 1904, p. 13.

- ^ a b De Wolfe 1904, p. 23.

- ^ Moffat 1917, p. 12.

- ^ a b "A BOYAR WEDDING FEAST". hillwoodmuseum.org. Hillwood Estate, Museum & Gardens. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ Andrey Somov (1890–1907). "Маковский". Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary: In 86 Volumes (82 Volumes and 4 Additional Volumes). St. Petersburg.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d "Makovsky Konstantin Egorovich, artist". Krasnoselsky district of Moscow. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Biography of Konstantin Makovsky". blouinartinfo.com. Blouin Media. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019.

- ^ "Особенности реализма в России". philol.msu.ru (in Russian). Faculty of Philology, Moscow State University. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020.

- ^ Conover 2001, p. 246.

- ^ "Russian Wedding Feast by K E Makowski". www.etsy.com. Etsy. Retrieved 31 October 2015.

- ^ Schumann 1891, p. 26.

- ^ "Konstantin Makovsky". Blouin Artinfo. Archived from the original on 4 July 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Konstantin Makovsky – Tsars Painter". www.hillwoodmuseum.org. Hillwood Museum. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "A Boyar Wedding Feast". www.google.com/culturalinstitute. Google Cultural Institute. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^

"Chit-Chat by Cable". Chicago Daily Tribune. 30 August 1885. p. 3. Retrieved 6 November 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^

"Telegraphic Brevities". Sacramento Daily Record-Union. 17 December 1885. p. 1. Retrieved 6 November 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Russian Paintings Sold". The New York Times. 24 January 1936. p. 17.

- ^ "Do You Believe It?". www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience. PBS American Experience. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Ripley Sale Ends Today". The New York Times. 26 August 1949. p. 16.

- ^ "Special Issue Commemorating the Bicentenary of The Royal Academy (1768–1968)", The Burlington Magazine, 110 (789), Burlington Magazine: xix, 1968, JSTOR 875780

Bibliography

- Champlin, John Denison; Perkins, Charles Callahan, eds. (1900). Cyclopedia of Painters and Paintings. Vol. 4. Charles Scribner’s Sons. p. 415.

- Conover, Jennifer R., ed. (2001). Toasts for Every Occasion. New American Library. p. 246. ISBN 0-451-20301-1.

- Coffin, William A. (1917), "Russian Art", The Mentor, 5 (19), Mentor Association, Inc: 1–11

- De Wolfe, Tensard, ed. (1904), "Russian Wedding Feast", The Index, 11 (11), The Index Company: 23

- Fry, Roger Eliot; Goodwin, Craufurd D.W. (1999). Art and the Market: Roger Fry on Commerce in Art. The University of Michigan Press. p. 108. ISBN 0-472-10902-2.

- Keyser, E.N. (1904), "Russian Art – Its Strength and Its Weakness", Brush and Pencil, 14 (3), The Brush and Pencil Publishing Company: 161–76, doi:10.2307/25503729, JSTOR 25503729

- Moffat, W.D. (1917), "The Open Letter", The Mentor, 5 (19), Mentor Association, Inc: 12

- Schumann, Charles William (1891). Art and Gems. C.W. Schumann. pp. 25–27.

- Slocum, William Neill (1904), Common Sense, vol. 4, Page-Davis Co., p. 13

External links[edit]

- La Belle Epoque en Europe Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine