Abraham Lincoln and slavery

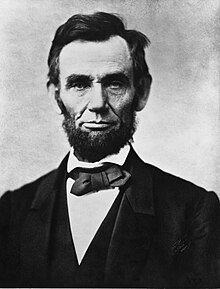

Abraham Lincoln | |

|---|---|

| |

| 16th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 | |

| Vice President | Hannibal Hamlin Andrew Johnson |

| Preceded by | James Buchanan |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1809 Hodgenville, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | April 15, 1865 (age 56) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Republican Party (1854–1865) National Union Party (1864–1865) |

| Other political affiliations | Whig Party (Before 1854) |

Abraham Lincoln's position on slavery was one of the central issues in American history.

Lincoln often expressed moral opposition to slavery in public and private.[1] Initially, he expected to bring about the eventual extinction of slavery by stopping its further expansion into any U.S. territory, and by proposing compensated emancipation (an offer Congress applied to Washington, D.C.) in his early presidency. Lincoln stood by the Republican Party platform in 1860, which stated that slavery should not be allowed to expand into any more territories. Lincoln believed that the extension of slavery in the South, Mid-west, and Western lands would inhibit "free labor on free soil". In the 1850s, Lincoln was politically attacked as an abolitionist, but he did not consider himself one; he did not call for the immediate end of slavery everywhere in the U.S. until the proposed 13th Amendment became part of his party platform for the 1864 election.[2]

In 1842, Abraham Lincoln married Mary Todd, who was a daughter of a prominent slave-owning family from Kentucky.[3] Lincoln returned to the political stage as a result of the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act and soon became a leading opponent of the "Slaveocracy"—that is the political power of the southern slave owners. The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, written to form the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, included language, designed by Stephen A. Douglas,[4] which allowed the settlers to decide whether they would or would not accept slavery in their region. Lincoln saw this as a repeal of the 1820 Missouri Compromise which had outlawed slavery above the 36-30' parallel.

During the American Civil War, Lincoln used the war powers of the presidency to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared "all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free" but exempted border states and those areas of slave states already under Union control. As a practical matter, at first the Proclamation could only be enforced to free those slaves who had already escaped to the Union side. However, millions more were freed as more areas of the South came under Union control. Lincoln pursued various plans to colonize free Blacks outside the United States, but none of these had a major effect.

Early years

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky[5] (now LaRue County). His family attended a Separate Baptists church, which had strict moral standards and opposed alcohol, dancing, and slavery.[6] The family moved north across the Ohio River to free (i.e., non-slave) territory and made a new start in Perry County, Indiana. Lincoln later noted that this move was "partly on account of slavery" but mainly due to land title difficulties.[7] As a young man, he settled in the free state of Illinois.

1840s - 1850s

Legal and political

Lincoln, the leader most associated with the end of slavery in the United States, came to national prominence in the 1850s, following the advent of the Republican Party, which opposed the expansion of slavery. Earlier, as a member of the Whig Party in the Illinois General Assembly, Lincoln issued a written protest of the assembly's passage of a resolution stating that slavery could not be abolished in Washington, D.C.[8][9] In 1841, he won a court case (Bailey v. Cromwell), representing a black woman and her children who claimed she had already been freed and could not be sold as a slave.[10] In 1845, he successfully defended Marvin Pond (People v. Pond)[11] for harboring the fugitive slave John Hauley. In 1847, he lost a case (Matson v. Rutherford) representing a slave owner (Robert Matson) claiming return of fugitive slaves. While a congressman from Illinois in 1846 to 1848, Lincoln supported the Wilmot Proviso, which, if it had been adopted, would have banned slavery in any U.S. territory won from Mexico.[12] Lincoln, in collaboration with abolitionist Congressman Joshua R. Giddings, wrote a bill to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia with compensation for the owners, enforcement to capture fugitive slaves, and a popular vote on the matter.[13]

Lincoln had left politics until he was drawn back into it by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed territories to decide for themselves whether they would allow slavery. Lincoln was morally opposed to slavery and politically opposed to any expansion of it.[1] On October 16, 1854, in his "Peoria Speech", Lincoln declared his opposition to slavery, which he repeated in his route to presidency.[14] Speaking in his Kentucky accent, with a very powerful voice,[15] he said the Kansas Act had a "declared indifference, but as I must think, a covert real zeal for the spread of slavery. I cannot but hate it. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world..."[16]

Since the 1840s Lincoln had been an advocate of the American Colonization Society program of colonizing blacks in Liberia. In an October 16, 1854,[17]: a speech at Peoria, Illinois[18] (transcribed after the fact by Lincoln himself),[17]: b Lincoln points out the immense difficulties of such a task are an obstacle to finding an easy way to quickly end slavery.[17]: c [19]

- If all earthly power were given to me [...] my first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia,—to their own native land. But a moment’s reflection would convince me that whatever of high hope (as I think there is) there may be in this, in the long run, its sudden execution is impossible.[20][21]

According to historian Paul Escott, Lincoln thus favored a system of gradual emancipation that would allow for controlled management of free Negroes.[21]

Letter to Joshua Speed

In 1855, Lincoln wrote to Joshua Speed, a personal friend and slave owner in Kentucky:

You know I dislike slavery; and you fully admit the abstract wrong of it... I also acknowledge your rights and my obligations, under the constitution, in regard to your slaves. I confess I hate to see the poor creatures hunted down, and caught, and carried back to their stripes, and unrewarded toils; but I bite my lip and keep quiet. In 1841 you and I had together a tedious low-water trip, on a Steam Boat from Louisville to St. Louis. You may remember, as I well do, that from Louisville to the mouth of the Ohio, there were, on board, ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons. That sight was a continued torment to me; and I see something like it every time I touch the Ohio, or any other slave-border. It is hardly fair for you to assume, that I have no interest in a thing which has, and continually exercises, the power of making me miserable. You ought rather to appreciate how much the great body of the Northern people do crucify their feelings, in order to maintain their loyalty to the Constitution and the Union. . . How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes." When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equal, except negroes, and foreigners, and catholics." When it comes to this I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretence of loving liberty— to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be take pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.[22]

Lincoln-Douglas debates 1858

Many of Lincoln's public anti-slavery sentiments were presented in the seven Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858 against his opponent, Stephen Douglas, during Lincoln's unsuccessful campaign for a seat in the U.S. Senate (which was decided by the Illinois legislature). Douglas advocated "popular sovereignty" and self-government, which would give the citizens of a territory the right to decide if slavery would be legal there.[23] Douglas criticized Lincoln as being inconsistent, saying he altered his message and position on slavery and on the political rights of freed blacks in order to appeal to the audience before him, as northern Illinois was more hostile to slavery than southern Illinois.

Lincoln stated that Negroes had the rights to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" in the first of the Lincoln–Douglas debates.[24] Publicly, Lincoln said he was not advocating Negro suffrage in his speech in Columbus, Ohio on September 16, 1859.[17]: d

This might have been a strategy speech used to gain voters, as Douglas had accused Lincoln of favoring negroes too much as well.[25]

1860 Republican presidential nomination

The Republican Party was committed to restricting the growth of slavery, and its victory in the election of 1860 was the trigger for secession acts by Southern states. The debate before 1860 was mainly focused on the Western territories, especially Kansas and the popular sovereignty controversy.

Lincoln was nominated as the Republican candidate for president in the election of 1860. Lincoln was opposed to the expansion of slavery, but held that the federal government was prevented by the Constitution from banning slavery in states where it already existed. His plan was to halt the spread of slavery, and to offer monetary compensation to slave-owners in states that agreed to end slavery (see Compensated emancipation). He was considered a moderate within his party, as there were some who wanted the immediate abolition of slavery.

Presidency 1861-1865

Corwin amendment

Because he thought it was essentially a reaffirmation of terms already in the Constitution, Lincoln supported the compromise Corwin amendment in 1861. Before Lincoln became President, the proposed amendment was passed by Congress and later two states, but was abandoned once the Civil War began. It would have explicitly prohibited congressional interference with slavery in states where it already existed. The Corwin amendment was a late attempt at reconciliation, but it also was a measure of reassurance to the slave-holding border states that the federal government was not intent on taking away their powers.[26] Nonetheless, Lincoln was bitterly attacked throughout the secession crisis and Civil War regarding his anti-slavery views. Many of Lincoln's opponents, especially in the South, regarded him as an "abominable" abolitionist, even before the war.[27]

Emancipation

At the beginning of the war, Lincoln prohibited his generals from freeing slaves even in captured territories. On August 30, 1861, Major General John C. Frémont, the commander of the Union Army in St. Louis, proclaimed that all slaves owned by Confederates in Missouri were free. Lincoln opposed allowing military leaders to take executive actions that were not authorized by the government, and realized that such actions could induce slaveowners in border states to oppose the Union or even start supporting the enemy. Lincoln demanded Frémont modify his order and free only slaves owned by Missourians actively working for the South. When Frémont refused, he was replaced by the conservative General Henry Wager Halleck.

Radical Republicans such as William P. Fessenden of Maine and Charles Sumner supported Frémont. Fessenden described Lincoln's action as "a weak and unjustifiable concession to the Union men of the border states" and Sumner writing in a letter to Lincoln how sad it was "to have the power of a god and not use it godlike."

The situation was repeated in May 1862, when General David Hunter began enlisting black soldiers in the occupied district under his control. Soon afterwards Hunter issued a statement that all slaves owned by Confederates in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina were free. Despite the pleas of Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, Lincoln ordered Hunter to disband the black 1st South Carolina Regiment and to retract his proclamation. At all times Lincoln insisted that he controlled the issue—only he had the war powers. Lincoln's view was that in order for freedmen to effectively and legally rely on the promise and declaration of freedom it had to be grounded in the president's constitutional authority.[28]

On August 22, 1862, just a few weeks before signing the Proclamation and after he had already discussed a draft of it with his cabinet in July, he wrote a letter in response to an editorial by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune which had urged complete abolition. Lincoln differentiates between "my view of official duty"—that is, what he can do in his official capacity as President—and his personal views. Officially he must save the Union above all else; personally he wanted to free all the slaves:

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views. I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men everywhere could be free.[29]

Just one month after writing this letter, Lincoln issued his first Emancipation Proclamation, which announced that at the beginning of 1863, he would use his war powers to free all slaves in states still in rebellion (as they came under Union control).

Also revealing was his letter[30] ([31]) a year later to James C. Conkling of August 26, 1863, which included the following excerpt:

There was more than a year and a half of trial to suppress the rebellion before the proclamation issued, the last one hundred days of which passed under an explicit notice that it was coming, unless averted by those in revolt, returning to their allegiance. The war has certainly progressed as favorably for us, since the issue of proclamation as before. I know, as fully as one can know the opinions of others, that some of the commanders of our armies in the field who have given us our most important successes believe the emancipation policy and the use of the colored troops constitute the heaviest blow yet dealt to the Rebellion, and that at least one of these important successes could not have been achieved when it was but for the aid of black soldiers. Among the commanders holding these views are some who have never had any affinity with what is called abolitionism or with the Republican party policies but who held them purely as military opinions. I submit these opinions as being entitled to some weight against the objections often urged that emancipation and arming the blacks are unwise as military measures and were not adopted as such in good faith.

You say you will not fight to free negroes. Some of them seem willing to fight for you; but, no matter. Fight you, then exclusively to save the Union. I issued the proclamation on purpose to aid you in saving the Union. Whenever you shall have conquered all resistance to the Union, if I shall urge you to continue fighting, it will be an apt time, then, for you to declare you will not fight to free negroes.

I thought that in your struggle for the Union, to whatever extent the negroes should cease helping the enemy, to that extent it weakened the enemy in his resistance to you. Do you think differently? I thought that whatever negroes can be got to do as soldiers, leaves just so much less for white soldiers to do, in saving the Union. Does it appear otherwise to you? But negroes, like other people, act upon motives. Why should they do any thing for us, if we will do nothing for them? If they stake their lives for us, they must be prompted by the strongest motive—even the promise of freedom. And the promise being made, must be kept. ...

Peace does not appear so distant as it did. I hope it will come soon, and come to stay; and so come as to be worth the keeping in all future time. It will then have been proved that, among free men, there can be no successful appeal from the ballot to the bullet; and that they who take such appeal are sure to lose their case, and pay the cost. And then, there will be some black men who can remember that, with silent tongue, and clenched teeth, and steady eye, and well-poised bayonet, they have helped mankind on to this great consummation; while, I fear, there will be some white ones, unable to forget that, with malignant heart, and deceitful speech, they strove to hinder it.

Lincoln addresses the issue of his consistency (or lack thereof) between his earlier position and his later position of emancipation in an 1864 letter to Albert G. Hodges.[32] In that letter, Lincoln states his ethical opposition to slavery, that he did not think he had the constitutional power to abolish it everywhere initially, and that emancipation became necessary for the preservation of the Union.

Compensation

President Lincoln advocated that slave owners be compensated for emancipated slaves.[33] On March 6, 1862 President Lincoln in a message to the U.S. Congress stated that emancipating slaves would create economic "inconveniences" and justified compensation to the slave owners. The resolution was adopted by Congress, however, the Southern States refused to comply.[34] On July 12, 1862 President Lincoln in a conference with Congressmen from Kentucky, Maryland, Delaware, and Missouri encouraged their respective states to adopt emancipation legislation that gave compensation to the slave owners.[35] On July 14, 1862 President Lincoln sent a bill to Congress that allowed the Treasury to issue bonds at 6% interest to states for slave emancipation compensation to the slave owners. The bill was never voted on by Congress.[36] At the Hampton Roads Conference in 1865, Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander H. Stephens stated that President Lincoln was in favor of a "fair indemnity", possibly $500,000,000, in compensation for emancipated slaves.[37]

Colonization

Colonization of freed slaves was long seen by many as an answer to the problem of slavery. One of President Abraham Lincoln's policies during his administration was the voluntary colonization of African American Freedmen. Historians have debated and have remained divided over whether Lincoln's racial views (or merely his acceptance of the political reality) included that African Americans could not live in the same society as white Americans. Benjamin Butler stated that Lincoln in 1865 firmly denied that "racial harmony" would be possible in the United States.[38] One view (known to scholars as the "lullaby" theory) is that Lincoln adopted colonization for Freedmen in order to make his Emancipation Proclamation politically acceptable.[38] This view has been challenged with new evidence of the Lincoln administration's attempts to colonize freedmen in British Honduras after the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863.[38]

Bureau of Emigration

President Lincoln supported colonization during the Civil War as a practical response to newly freed slaves. At his urging, Congress included text in the Second Confiscation Act of 1862 indicating support for Presidential authority to recolonize consenting Africans.[39] With this authorization, Lincoln created an agency to direct his colonization projects. At the suggestion of Lincoln, in 1862, Congress appointed $600,000 to fund and created the Bureau of Emigration in the U.S. Department of the Interior. To head that office Lincoln appointed the energetic Reverend James Mitchell, a leader of the American Colonization Party.[40][41] Lincoln had known Mitchell since 1853, when Mitchell visited Illinois. Mitchell's Washington D.C.'s office was in charge of implementing Lincoln's voluntary colonization policy of African Americans. In his annual December message to Congress that year (his second "State of the Union" Message), he reiterated his strong support for government expenditure on colonization for those who wanted to go, but he also noted that objections to free blacks remaining in the United States were baseless, "if not sometimes malicious." [42] In 1862, Lincoln mentioned colonization favorably in his preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. Much concerning the controversial Bureau of Emigration is unknown today, as Mitchell's papers, that kept record of the office were lost after his death in 1903.[41]

Chiriqui Improvement Company

President Lincoln first proposed a Panama colony for Blacks in October 1861. Several hundred acres of Chiriquí Province in Panama (then a part of Gran Colombia) had in 1855 been granted to the Chiriqui Improvement Company for coal mining. The Company supplied the U.S. Navy with half-price coal during the war, but required more workers.[43] Congress gravitated towards this plan in mid-1862, and Lincoln appointed Kansas Senator Samuel Pomeroy to oversee it. Pomeroy promised 40 acres and a job to willing Blacks, and chose 500 of 13,700 who applied.[39] Lincoln signed a contract with businessman Ambrose W. Thompson, the owner of the land, and made plans to send tens of thousands of African Americans. Pomeroy secured $25,000 from Congress to pay for transportation and equipment.[39]

The plan was suspended in early October 1862 before a single ship sailed though, apparently due to diplomatic protests from neighboring Central American governments and the uncertainty raised by the Colombian Civil War (1860–1862). The plan also violated the 1850 Clayton–Bulwer Treaty prohibiting US and UK colonization of Central America.[39] Lincoln hoped to overcome these complications by having Congress make provision for a treaty for African American emigration, much as he outlined in his Second Annual Message of December 1, 1862, but the Chiriquí plan appears to have died over the New Year of 1863 as revelations of the corrupt interest of his acquaintance Richard W. Thompson and Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher likely proved too much to bear in political terms.[44]

Ile à Vache

In December 1862, Lincoln signed a contract with businessman Bernard Kock to establish a colony on the Ile à Vache near Haiti. 453 freed slaves departed for the island from Fort Monroe, Virginia. A government investigation had deemed Kock untrustworthy, and Secretary of State William Seward stopped the plan from going forward after learning of Kock's involvement.[45]

Poor planning, an outbreak of smallpox, and financial mismanagement by Kock left the colonists under-supplied and starving, according to early reports. 292 colonists remained on Ile a Vache in 1865; 73 had moved to Aux Cayes on Haiti.[45] The United States Navy arrived to rescue survivors after less than one year on the island.[46]

British West Indies

In addition to Panama and Haiti, Mitchell's office also oversaw attempts at colonization in British Honduras and elsewhere in the British West Indies. Lincoln believed that by dealing with the comparatively stable British Government, he could avoid some of the problems that plagued his earlier attempts at colonization with private interests.[47]

He signed an agreement on June 13, 1863, with John Hodge of British Honduras that authorized colonial agents to recruit ex-slaves and transport them to Belize from approved ports in Philadelphia, New York, and Boston.[48] Later that year the Department of the Interior sent John Willis Menard, a free African-American clerk who supported colonization, to investigate the site for the government. British authorities pulled out of the agreement in December, fearing it would disrupt their position of neutrality in the Civil War.[49]

The question of when Lincoln abandoned colonization, if ever, has aroused considerable debate among historians.[50] The government funded no more colonies after the rescue of the Ile a Vache survivors in early 1864, and Congress repealed most of the colonization funding that July.

Whether Lincoln's opinion had changed is unknown. He left no surviving statements in his own hand on the subject during the last two years of his presidency, although he apparently wrote Attorney General Edward Bates in November 1864 to inquire whether earlier legislation allowed him to continue pursuing colonization and to retain Mitchell's services irrespective of the loss of funding.[51][52] An entry in the diary of presidential secretary John Hay dated July 2, 1864, says that Lincoln had "sloughed off" colonization, though without much elaboration.[53] In a later report, General Benjamin F. Butler claimed that Lincoln approached him in 1865 a few days before his assassination, to talk about reviving colonization in Panama.[54] Historians have long debated the validity of Butler's account, as it was written many years after the fact and Butler was prone to exaggeration of his own exploits as a general.[55] Recently discovered documents prove that Butler and Lincoln did indeed meet on April 11, 1865, though whether and to what extent they talked about colonization is not recorded except in Butler's account.[56] On that same day, Lincoln gave a speech supporting a form of limited suffrage for blacks.

Much of the present debate revolves around whether to accept Butler's story. If rejected, then it appears that Lincoln "sloughed off" colonization at some point in mid-1864. If it is accepted, then Lincoln remained a colonizationist at the time of his death. This question is compounded by the unclear meaning of Hay's diary, and another article by Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, which suggests that Lincoln intended to revive colonization in his second term. In either case, the implications for understanding Lincoln's views on race and slavery are strong.[57]

Citizenship and limited suffrage

In his second term as president, on April 11, 1865, Lincoln gave a speech supporting a form of limited suffrage extended to what Lincoln described as the more "intelligent" blacks and those blacks who had rendered special services to the nation.[58] Lincoln assassin, John Wilkes Booth, attended the speech and determined to kill Lincoln for supporting citizenship for blacks.[59]

In analyzing Lincoln's position historian Eugene H. Berwanger notes:

During his presidency, Lincoln took a reasoned course which helped the federal government both destroy slavery and advance the cause of black suffrage. For a man who had denied both reforms four years earlier, Lincoln's change in attitude was rapid and decisive. He was both open-minded and perceptive to the needs of his nation in a postwar era. Once committed to a principle, Lincoln moved toward it with steady, determined progress.[60]

Views on African Americans

Known as the Great Emancipator, Lincoln was a complicated figure who wrestled with his own views on race.[61] Lincoln's primary audience were white voters. Lincoln's views on slavery, race equality, and African American colonization are often intermixed.[61] During the 1858 debates with Stephen Douglas, Lincoln expressed his contemporary view that he believed whites were superior to blacks.[61] Lincoln stated he was against miscegenation and blacks to serve as jurors. While President, as the American Civil War progressed, Lincoln advocated or implemented anti-racist policies including the Emancipation Proclamation and limited suffrage for African Americans.[61] Former slave and leading abolitionist, Frederick Douglass once observed of Lincoln: "In his company, I was never reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color".[62] Douglass praised Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation; however, he stated that Lincoln "was preeminently the white man’s President, entirely devoted to the welfare of white men."[63] In his past, Lincoln lived in a middle-class, racially mixed neighborhood of Springfield, Illinois; one of his long-time neighbors, Jameson Jenkins (who may have been born a slave), had come from North Carolina and was publicly implicated in the 1850s as a Springfield conductor on the underground railroad, sheltering escaped slaves. In 1861, Lincoln called on Jenkins to give him a ride to the train depot, where Lincoln delivered his farewell address before leaving Springfield for the last time.[64] Generations through changing times have interpreted independently Lincoln's views on African Americans.[61]

See also

- George Washington and slavery

- Thomas Jefferson and slavery

- John Quincy Adams and abolitionism

- Timeline of the African-American Civil Rights Movement

References

- ^ a b Striner, Richard (2006). Father Abraham: Lincoln's Relentless Struggle to End Slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-19-518306-1.

- ^ Foner (1970), Free Soil, Free Labor

- ^ "Mary Todd Lincoln".[dead link]

- ^ "Mr. Lincoln's White House: an examination of Washington DC during Abraham Lincoln's Presidency". Mrlincolnswhitehouse.org. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Donald (1996), pp. 20–22.

- ^ Donald (1996), pp. 22–24.

- ^ Sandburg (1926), p. 20.

- ^ "Lincoln on Slavery". Retrieved November 15, 2009.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham (1907). "Injustice the Foundation of Slavery". In Marion Mills Miller (ed.). Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln. Vol. 3. New York: Current Literature. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Adams, Carl (Fall–Winter 2008). "Lincoln's First Freed Slave A Review of Bailey v. Cromwell, 1841". Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society. 101 (3–4). Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ^ "Lincoln Law Practice – People v Pond".

- ^ Holzer, p. 63.

- ^ Harris, William C. (2007). Lincoln's Rise to the Presidency. University Press of Kansas. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7006-1520-9.; Foner, Eric (2010). The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. W.W. Norton. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-393-06618-0..

- ^ Thomas (2008), pp. 148–152.

- ^ White, p. 199.

- ^ Basler (1953), p. 255.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d

"Mr. Lincoln and Freedom". Abraham Lincoln Institute.

- a. "Speech at Peoria, October 16, 1854". Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- b. "Preface by Lewis Lehrman". Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- c. "1854". Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- d. "The progress of Abraham Lincoln's opposition to slavery". Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^

"Abraham Lincoln at Peoria: The Turning Point: Getting Right with the Declaration of Independence". Lincolnatpeoria.com. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Lincoln on Slavery". udayton.edu. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham. "Mr. Lincoln's Reply". First Joint Debate at Ottawa. bartleby.com. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Escott, Paul (2009)"What Shall We Do with the Negro?" University of Virginia Press, p. 25.

- ^ "Abraham Lincoln's 1855 Letter to Joshua Speed". Showcase.netins.net. Retrieved October 12, 2013.

- ^ "32b. The Lincoln-Douglas Debates". US History. Retrieved April 28, 2014.

- ^ "U S Constitution – The Lincoln–Douglas Debates, First Joint Debate". Usconstitution.com. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

- ^ "Vespasian Warner's recount of events leading up to the Lincoln–Douglas Debate". Moore–Warner Farm Management. Archived from the original on January 26, 2009. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Abraham Lincoln and the Corwin Amendment

- ^ Jenkins, Sally, and John Stauffer. The State of Jones. New York: Anchor Books edition/Random House, 2009 (2010). ISBN 978-0-7679-2946-2, p. 72

- ^ Cox, LaWanda (1981). Lincoln and Black Freedom: A Study in Presidential Leadership. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-0-87249-400-8.

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham. "Letter to Horace Greeley, August 22, 1862". In Miller, Marion Mills (ed.). Life and Works of Abraham Lincoln. Current Literature. Retrieved January 24, 2011.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "Abraham Lincoln's Letter to James Conkling". Showcase. Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cuomo and Holzer, Lincoln on Democracy, 1990, p. 292

- ^ "1864 letter to Albert G. Hodges, in which Lincoln explains how he came to change his position on abolition".

- ^ Lincoln, Abraham (December 1, 1862). Abraham Lincoln's Second Annual Message of 1862 (Speech). Presidential speech. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012.

- ^ Metcalf (August, 1900), Lincoln's Attitude For Emancipation with Compensation For Owners of Slaves, The Pacific Monthly, Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 151.

- ^ Metcalf (August, 1900), Lincoln's Attitude For Emancipation with Compensation For Owners of Slaves, The Pacific Monthly, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 152, 153.

- ^ Metcalf (August, 1900), Lincoln's Attitude For Emancipation with Compensation For Owners of Slaves, The Pacific Monthly, Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 153.

- ^ Metcalf (August, 1900), Lincoln's Attitude For Emancipation with Compensation For Owners of Slaves, The Pacific Monthly, Vol. 4, No. 4, p. 154.

- ^ a b c Magness and Page (2011), Colonization After Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement, chapter 11.

- ^ a b c d Oubre, Forty Acres and a Mule (1978), p. 4.

- ^ Magness & Page, Emancipation After Colonization (2011), p. 4.

- ^ a b Magness, Phillip W. (September 2011). "James Mitchell and the Mystery of the Emigration Office Papers". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. 32 (2): 50–62. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- ^ Second Annual Message December 1, 1862

- ^ Oubre, Forty Acres and a Mule (1978), pp. 3–4. "As early as October, 1861, Lincoln proposed colonizing Negroes on the Chiriqui Improvement Company grant in the district of Panama. In 1855 the company had gained control of several hundred thousand acres of rich coal land on the Isthmus of Panama. During the war the company contracted to provide the Navy Department with coal at one half the cost in the United States. In order to meet the demands of the Department of the Navy the company needed laborers for its coal mines.

- ^ Page, Sebastian N. (2011). "Lincoln and Chiriquí Colonization Revisited". American Nineteenth Century History. 12 (3): 289–325. doi:10.1080/14664658.2011.626160.

- ^ a b Oubre, Forty Acres and a Mule (1978), p. 5.

- ^ Lockett, James D. (1991). "Abraham Lincoln and Colonization". Journal of Black Studies. 21 (4): 428–444. doi:10.1177/002193479102100404.

- ^ "Lincoln and Black Colonization," Britannica.com, Retrieved 2011-04-23

- ^ Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page, Colonization after Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement (University of Missouri Press: 2011), Chapter 3 [1]

- ^ Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page, Colonization after Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement (University of Missouri Press: 2011), Chapter 5 [2]

- ^ For a summary of this debate see Sebastian N. Page, "Lincoln on Race," American Nineteenth Century History, Vol. 11, No. 1, March 2010

- ^ Phillip W. Magness and Sebastian N. Page, Colonization after Emancipation: Lincoln and the Movement for Black Resettlement (University of Missouri Press: 2011), p. 98

- ^ Bates to Lincoln, Opinion on James Mitchell, November 30, 1864, Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress, Retrieved 2011-11-17 [3]

- ^ Michael Burlingame and John R. Ettlinger, eds., Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999),

- ^ Benjamin F. Butler, Autobiography and Personal Reminiscences of Major General Benjamin F. Butler (Boston: A. M. Thayer, 1892), p. 903

- ^ Mark E. Neely, "Abraham Lincoln and Black Colonization: Benjamin Butler's Spurious Testimony," Civil War History 25 (1979), pp. 77–83

- ^ Phillip W. Magness, "Benjamin Butler's Colonization Testimony Reevaluated." Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Vol. 29, No. 1, Summer 2008, [4]

- ^ Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Lincoln on Race and Slavery Princeton University Press, 2009, foreword

- ^ "Last Public Address". Speeches and Writings. Abraham Lincoln Online. April 11, 1865. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ Swanson, p. 6

- ^ "Lincoln's Constitutional Dilemma: Emancipation and Black Suffrage". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. Archived from the original on August 21, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Gates (February 12, 2009),Was Lincoln a Racist?

- ^ Douglass, pp. 259–260.

- ^ "Oration in Memory of Abraham Lincoln by Frederick Douglass". Teachingamericanhistory.org. April 14, 1876. Retrieved October 29, 2011.

- ^ "Lincoln Home – The Underground Railroad in Lincoln's Neighborhood" (PDF). National Park Service - US Dept. of the Interior. February 2008. Retrieved August 25, 2012.

Further reading

- Belz, Herman. Abraham Lincoln, Constitutionalism, and Equal Rights in the Civil War Era (1998)

- Burton, Vernon. The Age of Lincoln (2009)

- DiLorenzo, Thomas J. The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War (2003). ISBN 9780761536413. OCLC 716369332 an intense attack on Lincoln

- Donald, David H. Lincoln (1995) a standard scholarly biography

- Escott, Paul D."What Shall We Do with the Negro?" Lincoln, White Racism, and Civil War America. University of Virginia Press, (2009). ISBN 9780813927862

- Foner, Eric. The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery (2011); Pulitzer Prize; the standard scholarly account

- Finkelman, Paul. "Lincoln and Emancipation: Constitutional Theory, Practical Politics, and the Basic Practice of Law," Journal of Supreme Court History (2010) 35#3 pp. 243–266

- Fredrickson, George M. Big Enough to Be Inconsistent: Abraham Lincoln Confronts Slavery and Race (2009)

- Guelzo, Allen C.:

- Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. 1999.

- Defending Emancipation: Abraham Lincoln and the Conkling Letter, 1863. 2002.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "How Abe Lincoln Lost the Black Vote: Lincoln and Emancipation in the African American Mind". Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association. September 15, 2008. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- Harris, William C. With Charity for All: Lincoln and the Restoration of the Union (1997).

- Holzer, Harold (2004). Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9964-0.

- Jones, Howard; Abraham Lincoln and a New Birth of Freedom: The Union and Slavery in the Diplomacy of the Civil War (1999)

- Klingaman, William K. Final Freedom: The Civil War, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861–1865 (2001)

- McPherson, James M. Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (1992)

- Manning, Chandra, “The Shifting Terrain of Attitudes toward Abraham Lincoln and Emancipation,” Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, 34 (Winter 2013), 18–39, historiography

- Rawley, James A. Abraham Lincoln and a Nation Worth Fighting For. Harlan-Davidson, (1996)

- Swanson, James. Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. Harper Collins, 2006. ISBN 978-0-06-051849-3

- Vorenberg, Michael. Final Freedom: The Civil War, the Abolition of Slavery, and the Thirteenth Amendment (2001)