Akritas plan

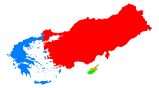

The Akritas plan was created in 1963 by the Greek Cypriot part of the government in Cyprus with the ultimate aim of weakening the Turkish Cypriot (ethnic Turks living in the Eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus) wing of the Cypriot government and then uniting Cyprus with Greece.[1] The desired union of Greek Cypriots with Greece was referred to as Enosis.

Background to the plan

In 1878 as a result of the Cyprus Convention, the United Kingdom received as a protectorate the island of Cyprus from the Ottoman Empire in exchange for United Kingdom's military support to the Ottoman Empire if Russia would attempt to take possession of territories of the Ottomans in Asia.[2] Britain then administered Cyprus until 1960. In 1955, a Greek Cypriot paramilitary organization called EOKA declared a rebellion of the entire Greek population (except for the communists) of the island to expel the British forces from the island and unite with Greece on the ground of self-determination of the inhabitants, and launched an armed struggle to achieve this aim, called enosis.[3] This caused a "Crete syndrome" within the Turkish Cypriot community, as its members feared that they would be forced to leave the island in such a case as was the case with Cretan Turks; as such, they preferred the continuation of the British rule and later, taksim, the division of the island. Due to the Turkish Cypriots' support for the British, the EOKA leader Georgios Grivas declared them an enemy. With the support of Turkey, which favored a policy of partition, the Turkish Cypriots formed the Turkish Resistance Organization.[4]

In 1960, the British gave in and turned power over to the Greek and Turkish Cypriots. A power sharing constitution was created for the new Republic of Cyprus which included both Turkish and Greek Cypriots holding power in Government. Three Treaties were written up to guarantee the integrity and security of the new republic: The Treaty of Establishment, the Treaty of Guarantee, and the Treaty of Alliance. According to constitution, Cyprus was to become an independent republic with a Greek Cypriot president and a Turkish Cypriot vice-president with full power sharing between Turkish and Greek Cypriots[citation needed].

Formation and aims

The Akritas plan was drawn by the minister of the interior, Polycarpos Georgadjis,[5] who was a close associate of the Greek Cypriot leader Archbishop Makarios, although there is no evidence that Makarios advocated the Akritas plan. The plan's course of action was to persuade the world community that too many rights had been given to the Turkish Cypriots and that the constitution had to be rewritten if the government was to be workable. Britain and the US had to be convinced that the Turkish Cypriots did not have to be afraid of Greek Cypriot political dominance in the island.

The next step of the plan was to cancel international treaties that existed to safeguard the republic, including the Treaty of Guarantee and the Treaty of Alliance. If a way could be found to dissolve the treaties legally, Union with Greece would be possible. The Treaties had been put into place by Britain, Greece and Turkey to safeguard the Republic and to protect the rights of the Greek and Turkish Cypriots.

The plan stated that if the Turkish Cypriots objected the changes and "attempted to block them by force", they should be "violently subjugated before foreign powers could intervene".[6] The ultimate aim was to change the constitution unilaterally.[7]

In November 1963, Greek Cypriot leader Makarios made a 13 point proposal to make the constitution more workable, which were rejected by the Turkish Cypriot Leadership on 16 December 1963. It said that the proposed amendments would undermine the constitution and weaken the Turkish Cypriot wing of the government[citation needed]. These proposals were allegedly a part of the plan.[8]

Between 21 and 22 December 1963, up to 133 Turkish Cypriots were killed by Greek Cypriots in what became known by Turkish Cypriots as Bloody Christmas.[9] About a quarter of the Turkish Cypriots, some 25,000 or so, subsequently fled their homes and lands and moved into enclaves.[10][11][12]

Key themes and elements of the Akritas plan

According to the copy of the plan leaked to the pro-Grivas Greek Cypriot newspaper[13] Patris, the plan consisted of two main sections, one delineating external tactics to be employed, and the other delineating internal tactics. The external tactics pointed to the Treaty of Guarantee as the first objective of an attack, with the statement that it was no longer recognized by Greek Cypriots. If the Treaty of Guarantee was abolished, there would be no legal roadblocks to enosis, which would happen through a plebiscite.[14]

Controversy and opinions

Greek Cypriot sources have accepted the authenticity of the Akritas plan, but controversy regarding its significance and implications persists.[15] It is a subject of debate whether the plan was actually implemented by President Makarios. Frank Hoffmeister wrote that the similarity of the military and political actions foreseen in the plan and undertaken in reality were "striking".[5] According to Paul Sant-Cassia, the plan "purported to project a plan at ethnic cleansing", which was in parallel to the Turkish Cypriot perception that the events of 1963-64 were part of a policy of extermination.[16]

Turkish Cypriot nationalistic narratives have presented the plan as a "blueprint for genocide"[15] and it is widely perceived as a plan for extermination in the Turkish Cypriot community.[17] Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs calls the plan a "conspiracy to dissolve the Republic of Cyprus, in pre-determined stages and methods, and to bring about the union of Cyprus with Greece".[18] According to scholar Niyazi Kızılyürek, however, the meaning later given to this plan was disproportionate and the plan was a "stupid" and impractical plan that got more attention than it deserved due to propaganda. He claimed that, in accordance to the plan, ELDYK troops should have taken action, which was not the case and led to Georgadjis shouting "traitors!" in front of their camp.[17] Calling the plan "infamous", scholar Evanthis Hatzivassiliou wrote that the aim of quick victory indicated the "confusion and wishful thinking of the Greek Cypriot side at that crucial moment".[19]

See also

- Cyprus

- History of Cyprus

- Modern history of Cyprus

- Timeline of Cypriot history

- Cyprus dispute

- Turkish Cypriot enclaves

- Kokkina exclave

- Cypriot refugees

- Cypriot intercommunal violence

References

- ^ Cyprus – The Republic of Cyprus (http://countrystudies.us/cyprus/12.htm), U.S. Library of Congress

- ^ Library of Congress

- ^ Cyprus: The Search for a Solution by David Hannay

- ^ Isachenko, Daria (2012). The Making of Informal States: Statebuilding in Northern Cyprus and Transdniestria. Palgrave Macmillian. p. 38-39. ISBN 9780230392069. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- ^ a b Hoffmeister, Frank (2006). Legal Aspects of the Cyprus Problem: Annan Plan And EU Accession. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 9789004152236.

- ^ Solsten, Eric. Cyprus – The Republic of Cyprus (http://countrystudies.us/cyprus/12.htm), U.S. Library of Congress

- ^ Isachenko 2012, p. 41.

- ^ Dubin, Marc; Morris, Damien. Cyprus. Rough Guides. p. 421. ISBN 9781858288635.

- ^ "British Turks asked to remember victims of Bloody Christmas 1963". northcyprusfreepress.com. 14 December 2010.

- ^ Kliot, Nurit (2007), "Resettlement of Refugees in Finland and Cyprus: A Comparative Analysis and Possible Lessons for Israel", in Kacowicz, Arie Marcelo; Lutomski, Pawel (eds) (eds.), Population resettlement in international conflicts: a comparative study, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-1607-X

{{citation}}:|editor2-first=has generic name (help). - ^ Tocci, Nathalie (2004), EU accession dynamics and conflict resolution: catalysing peace or consolidating partition in Cyprus?, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-4310-7.

- ^ Tocci, Nathalie (2007), The EU and conflict resolution: promoting peace in the backyard, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-41394-X.

- ^ "Conflict Between the States of Cyprus, 1963-1974". cyprus-conflict.net. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Hakki, Murat Metin (2007). The Cyprus Issue: A Documentary History, 1878-2006. I.B.Tauris. pp. 90–7. ISBN 9781845113926.

- ^ a b Bryant, Rebecca; Papadakis, Yiannis (2012). Cyprus and the Politics of Memory: History, Community and Conflict. I.B.Tauris. p. 249. ISBN 9781780761077.

- ^ Sant-Cassia, Paul (2005). Bodies of Evidence: Burial, Memory and the Recovery of Missing Persons in Cyprus. Berghahn Books. p. 23. ISBN 9781571816467.

- ^ a b Uludağ, Sevgül. "Ayın Karanlık Yüzü". Hamamböcüleri Journal. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ "THE "AKRITAS PLAN" AND THE "IKONES" DISCLOSURES OF 1980". Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ^ Hatzivassiliou, Evanthis (2006). Greece and the Cold War: Front Line State, 1952-1967. Routledge. p. 160. ISBN 9781134154883.