Antinatalism

Antinatalism is a philosophical position that assigns a negative value to birth, standing in opposition to natalism. It has been advanced by figures such as Arthur Schopenhauer,[1] Emil Cioran,[2] Peter Wessel Zapffe[3] and David Benatar.[4] Similar ideas can be seen in a fragment of Aristotle's Eudemus as "the wisdom of Silenus" and were discussed by Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche. Groups that encourage antinatalism, or pursue antinatalist policies, include the Voluntary Human Extinction Movement.

Arguments for antinatalism

Overpopulation

Some supporters of the antinatalist position assert that antinatalist policies could solve problems such as overpopulation, famine,[5] and depletion of non-renewable resources.[6] Some countries, such as India and China, have policies aimed at reducing the number of children per family, in an effort to curb serious overpopulation concerns and heavy strain on national resources, although these policies cannot be interpreted as discouraging all birth in general.[7]

According to antinatalists, overpopulation in the long term could lead to increased conflict over dwindling resources.[8] Paul Ehrlich, in his book The Population Bomb, argued that rapidly increasing population would soon create a crisis, and advocated coercive antinatalist policies on a global level in order to avert a Malthusian catastrophe. Although no crisis occurred in the timeframe he expected (his predictions in 1968 anticipated disaster by the late 1980s), he stands by the book and maintains that without future depopulation efforts the problem will worsen.[9]

Moral responsibility

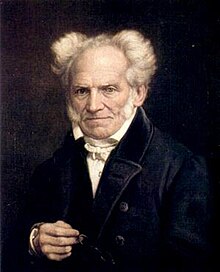

Arthur Schopenhauer argued that the value of life is ultimately negative because any positive experiences will always be outweighed by suffering which is a more powerful feeling.

Whoever wants summarily to test the assertion that the pleasure in the world outweighs the pain, or at any rate that the two balance each other, should compare the feelings of an animal that is devouring another with those of that other.[1]

Schopenhauer thought that the most reasonable position to take was not to bring children into the world:

If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone, would the human race continue to exist? Would not a man rather have so much sympathy with the coming generation as to spare it the burden of existence, or at any rate not take it upon himself to impose that burden upon it in cold blood?[10]

The Norwegian philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe remarked that children are brought into the world without consent or forethought:

In accordance with my conception of life, I have chosen not to bring children into the world. A coin is examined, and only after careful deliberation, given to a beggar, whereas a child is flung out into the cosmic brutality without hesitation.[11]

More recently, David Benatar has argued from the premise that the infliction of harm is morally wrong and to be avoided. He argues that the birth of a new person always entails nontrivial harm to that person, and therefore there is a moral imperative not to procreate.[4] His argument is based on the following premises:

- (1) The presence of pain is bad.

- (2) The presence of pleasure is good.

- (3) The absence of pain is good, even if that good is not enjoyed by anyone.

- (4) The absence of pleasure is not bad unless there is somebody for whom this absence is a deprivation.[4]

If someone exists, there is the presence of pain and the presence of pleasure. If no one exists, nothing bad happens and pain is avoided. They miss out on pleasure, but it seems 'ignorance is bliss' with the nonexistent. For Benatar, “any suffering at all would be sufficient to make coming into existence a harm”. The harm that coming into existence creates is avoidable and pointless. According to Benatar, it is always good to avoid harm whenever possible and therefore it is always good not to come into existence.[4]

According to Jimmy Alfonso Licon, procreation is only morally justified if there is some method for acquiring informed consent from a non-existent person, and due to the impossibility of this, procreation is therefore immoral.[12]

Happiness

Another argument for anti-natalism claims that assessments of human quality of life, particularly once we factor in various psychological biases, are not high enough to justify starting lives. This argument has been advanced by Benatar. Jason Marsh has criticized the argument in various ways but acknowledges that more work needs to be done to fully resolve the optimism and procreation problem.[13] In addition, becoming a parent and rearing children is not guaranteed to bring happiness. Using data sets from Europe and America, some scholars have found that, in the aggregate, parents report statistically significantly lower levels of happiness, life satisfaction, marital satisfaction, and mental well-being compared with non-parents.[14]

List of notable antinatalists

- Arthur Schopenhauer

- Gustave Flaubert

- Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann[15]

- Julius Bahnsen

- Matti Häyry[16][17][18]

- Ulrich Horstmann

- Philipp Mainländer

- Emil Cioran[2]

- David Benatar

- Jim Crawford

- Seana Shiffrin[19]

- Peter Wessel Zapffe[3]

- Thomas Ligotti[20]

- Edgar Saltus[21]

- Fernando Vallejo[22]

- Richard Stallman[23]

- Abul ʿAla Al-Maʿarri

- Doug Stanhope

- Albert Caraco

- Nina Paley[24]

Reflection in population control

In issues of human population control, antinatalism may favor practices of reducing population growth. In the period from the 1950s to the 1980s, concerns about global population growth and its effects on poverty, environmental degradation and political stability led to efforts to reduce population growth rates. While population control can involve measures that improve people's lives by giving them greater control of their reproduction, a few programs, most notably the Chinese government's "one-child policy", have resorted to coercive measures.

Criticism of antinatalism

Criticism of antinatalism may come from views that hold value in bringing potential future persons into existence, but there are also views holding that there is no such obligation.[25]

See also

- Abolitionism

- Catharism

- Childfree

- Church of Euthanasia

- Discovery Communications' 2010 hostage taker

- Extinction

- Greek Gospel of the Egyptians

- List of population concern organizations

- Misanthropy

- National Alliance for Optional Parenthood

- Negative Utilitarianism

- Nietzschean affirmation, a contrasting stance in favor of life, by a one-time follower of Schopenhauer

- Reproductive rights

- Shakers

- Skoptsy

References

- ^ a b Schopenhauer, Arthur. Parerga and Paralipomena, Short Philosophical Essays, Vol. 2, Oxford University Press, 2000, Ch. XII, Additional Remarks on the Doctrine of the Suffering of the World, § 149, p. 292.

- ^ a b E. M. Cioran, The Trouble with Being Born

- ^ a b Zapffe, Peter Wessel "The Last Messiah"

- ^ a b c d Benatar, David (2006). Better Never to Have Been. Oxford University Press, USA. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199296422.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-929642-2.

- ^ Dixon, Brian, E. (28 April 2008). In food crisis, family planning helps

- ^ Meadows, Donella (1993): Die neuen Grenzen des Wachstums: die Lage der Menschheit: Bedrohung und Zukunftschancen. Stuttgart: Dt. Verl.-Anst. ISBN 3-421-06626-4

- ^ Heinz Werner Wessler (30 January 2007): Indien – eine Einführung: Herausforderungen für die aufstrebende asiatische Großmacht im 21. Jahrhundert. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung

- ^ "Effects of Over-Consumption and Increasing Populations". 26 September 2001. Retrieved 19 June 2007

- ^ Paul R. Ehrlich; Anne H. Ehrlich (2009). "The Population Bomb Revisited" (PDF). Electronic Journal of Sustainable Development. 1 (3): 63–71. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur. Studies in Pessimism: The Essays. The Pennsylvania State University, 2005, p. 7.

- ^ To Be a Human Being (1989–90); the philosopher Peter Wessel Zapffe in his 90th year (1990 documentary, Tromsø Norway: Original Film AS).

- ^ Alfonso Licon, Jimmy (September 2012). "Immorality of Procreation". Think. 11 (32): 85–91. doi:10.1017/S1477175612000206.

- ^ Marsh, Jason (2014-09-01). "Quality of Life Assessments, Cognitive Reliability, and Procreative Responsibility". Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 89 (2): 436–466. doi:10.1111/phpr.12114. ISSN 1933-1592.

- ^ Belkin, Lisa. "Does Having Children Make You Unhappy?". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- ^ Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu/hartmann/

- ^ [1] Matti Häyry, The rational cure for prereproductive stress syndrome, Journal Of Medical Ethics, 2004, 30(4), pp. 377–378.

- ^ [2] Matti Häyry, The rational cure for prereproductive stress syndrome revisited, Journal Of Medical Ethics, 2005, 31(10), pp. 606–607.

- ^ [3] Matti Häyry, Arguments and Analysis in Bioethics, Rodopi, 2010, pp. 171–174.

- ^ Seana Shiffrin, Wrongful Life, Procreative Responsibility, and the Significance of Harm, Legal Theory 5, 117–148 (1999).

- ^ Thomas Ligotti, The Conspiracy against the Human Race

- ^ Saltus, E. The Philosophy of Disenchantment

- ^ Unidad Editorial Internet (24 March 2010). "Fernando Vallejo: 'No le veo ninguna razón a la vida, no la puedo defender' - Cultura - elmundo.es". Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "RMS -vs- Doctor, on the evils of Natalism". Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ "NinaPaley.com - ChildFree!". Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ Do Potential People Have Moral Rights? by Mary Anne Warren. Canadian Journal of Philosophy. Vol. 7, No. 2 (Jun., 1977), pp. 275–289 (online)

Further reading

- Morgan, Philip; Berkowitz King, Rosalind (2001). "Why Have Children in the 21st Century? Biological Predisposition, Social Coercion, Rational Choice". European Journal of Population. 17: 3–20.

- Steyn, Mark (December 14, 2007). "Children? Not if you love the planet". Orange County Register. Santa Ana, California. Archived from the original on 16 April 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

External links

Quotations related to Antinatalism at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Antinatalism at Wikiquote Works related to On the Sufferings of the World at Wikisource

Works related to On the Sufferings of the World at Wikisource