Archaeology of Afghanistan

Located on the strategic crossroads of Iran, India, China and Central Asia, Afghanistan boasts a diverse cultural and religious history.[1] The soil is rich with archaeological treasures and art that have for decades come under threat of destruction and damage. Archaeology of Afghanistan, mainly conducted by British and French antiquarians, has had a heavy focus on the treasure filled Buddhist monasteries that lined the silk road from the 1st c. BCE – 6th c. AD. Particularly the ancient civilizations in the region during the Hellenistic period and the Kushan Empire.[2] The world's oldest-known oil paintings, dating to the 7th c. AD, were found in caves in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley.[3] The valley is also home to the famous Buddhas of Bamiyan.

Many of these valuable artefacts are either stored in the National Museum of Afghanistan or continue to be uncovered in the field. Unfortunately they face serious threat of destruction and damage as a result of illegal trade, looting and the Taliban. The extremist religious group came to power in 1996, and ordered the destruction of many precious artefacts.[4] The group's recent seizure of control once again in 2021 has put many cultural heritage experts on alert.

History of archeology in Afghanistan[edit]

The first records of archaeological monuments in Afghanistan were observed by international travellers. Chinese voyagers on their way to visit holy Buddhist temples in Northern India were the first recorders of ancient cultural sites and artefacts. Accounts from 400 A.D. still inform historians of these sites.[5]: 4 The Chinese monk Xuanzang left records dating from the seventh century and detail descriptions of ancient Buddhist artefacts such as the Bamiyan temples.[5]: 4 Muslim travellers have kept records from their journeys in the eighth century and similarly describe monuments. European travellers subsequently take over the historical record.

Early 19th century marked the first archaeological investigation, both excavation and recording of historic sites in Afghanistan.[6] This work was commenced mainly after the British Indian Army officers travelled through the mainland and uncovered the treasures of Afghanistan's ancient history. Their inexhaustible curiosity and ability to amass raw archaeological information led to many significant discoveries and laid foundations for modern scientific archaeology.[6]

Two of these many investigation efforts deserve attention. During the period of antiquity, a British envoy by the name of James Lewis abandoned his post for the British East India Company at Agra in 1827 and headed north-east under the alias of Charles Masson.[7] His three-year travels would take him through Northern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan and he would later record detailed accounts of his travels for the Bombay Government in the Masson Bombay Dispatches in 1834.[8] This British antiquarian is also known to have surveyed and excavated a significant number of Buddhist artefacts around Kabul and Jalalabad alongside his discoveries from ancient Kapisa, Kushan capital of Begram in the 1st–3rd centuries C.E. The 30,000 coins he recovered during these excavations play a large role in defining the basis of Greco-Bactrain, Indo-Parthian, and Kushan numismatic history of Afghanistan.[6] Most of the treasures and artefacts that Lewis recovered were sent to the British Museum in London where most are housed today.

Further archeological research would not be conducted in the region until the French signed a 30-year contract with a newly independent Afghanistan in 1921–22. This contract established Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), giving the exclusive right of archeological research in the nation to France.[9] This agreement was renewed until 1978, not without revisions, and detailed accounts of the research conducted under this agreement can be found in the 32 volumes of the Mémoires des Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan. One clause of the agreement states that all archeological findings, except for gold, were to be divided evenly between France and Afghanistan until 1965 when all findings would be declared property of Afghanistan. Archeological materials collected by DAFA were sent to the Afghanistan National Museum in Kabul and the Museé national des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet in Paris.

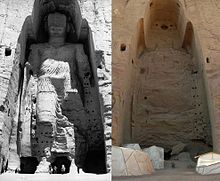

Archaeological research under DAFA traced the prosperous societies along the silk road mainly focusing on the Buddhist monasteries of the Kushan and Hellenistic periods. Full-scale excavations began in Hadda in 1926 by French Archaeologist, Barthoux. He recovered over 15,000 artefacts and fragments from eight monasteries and 500 stupas that were divided between Kabul and Paris.[9] The world-renowned Buddhas of Bamiyan are the most well-known artefacts from the Bamiyan Valley for being the largest standing Buddhas in the world and for their destruction by the Taliban. However, Bamiyan is also home to the famous Begram glasses and ivories that were uncovered by another French Archeologist, Hackin, in 1937.[8] The French monopoly of archeology began to erode in the mid 19th century as Afghanistan began archeological collaborations with nations such as Italy, Germany, Japan, India, U.K., U.S., and the Soviet Union. Research came to a halt as a result of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and has been slow to resume due to the instability of the region. Afghanistan has suffered civil wars and its conflict with the Taliban persists into the present day.

The Afghan Institute of Archaeology was established in 1966 which attracted the attention of many foreign missions and resulted in important discoveries post-Second World War. This institute also allowed for significant amount of research by Afghans themselves.[6] Ahmad-'Ali Kohzad of the Historical Society of Afghanistan (Anjoman-e Tarik-e Afghnestan, q.v.) surveyed portions of central Afghanistan while Shahibiya Mostamandi and Zemaryalai Tarzi initiated full scale excavations at Hadda (Tepe Sotor).

Destruction of artefacts[edit]

During the Soviet-Afghan War archeological sites like the ones at Hadda were leveled and many of the artefacts were destroyed. Looting was also rife during this conflict and continued through the civil wars that broke out after Soviets withdrew their forces in 1989, into the present day with ongoing conflict in the region.

Taliban Rule[edit]

The beginning of Taliban rule in 1996 put significant stress on museum curators and archaeologists in Afghanistan.[4]: 18 Historical artefacts and treasures immediately came under threat of destruction. This anxiety was perhaps not seriously recognised until the late 1990s when the National Museum of Afghanistan was subject to significant looting and damage under instruction of the Taliban.[10]: 18 One of the most shocking exhibits of Taliban power came about with the destruction of the famous Bamiyan Buddhas in March 2001,[11]: 62

The Taliban announced in July 1999 that they would outlaw any exhumation of historical sites in the country going forward.[12] : 11 The next step was on February 26, 2001, a statement was made by Mullah Mohammed Omar from the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan calling for the destruction of all non-Islamic iconography. He declared that "all statues and non-Islamic shrines located in the different parts of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan must be destroyed. Allah almighty is the only real shrine and all false shrines should be smashed."[11]: 61 The Islamic extremist group claimed that any representation of a God, or statue of worship that was not a representation of the Islamic God (Allah) or Islamic scripture was not fit for display.[13]: 17 Only a month after this statement was released, explosives were planted and detonated resulting in the collapse of the two Buddhas as well as causing significant further instability of the cliff niches.[11]: 77 Stability has been brought back to the Bamiyan Valley today and the historic Buddhas have been returned to their original stature as 3D light projections. The recent occupation of Afghanistan in February 2021[14] has put cultural experts on high alert as they remember the past consequences of Taliban rule. Current archaeological heritage sites and historical valuables across the country may be in danger once again. Due to Afghanistan’s long and rich cultural history, what the Taliban would consider ‘sacrilegious’ monuments are commonly encountered in the archaeological field and littered across the country. However, soon after reclaiming control, the Taliban released a statement, stating that they would endeavour to "robustly protect, monitor and preserve"[14] ancient artefacts, stop "illegal digs"[14] and protect "all historic sites".[14] Many academics consider this proclamation to be disingenuous and in truth, a strategic political move to avoid negative international attention.[1] The Taliban’s management of cultural sites and archaeological treasures in the future will confirm the validity of this statement.

On the August 18, 2021, the Taliban caused the destruction of an erected statue of political leader Abdul Ali Mazari in the province of Bamiyan.[15] In 1995, Mazari was killed by the Taliban because of his leadership and advocacy for the Shiite Hazaras, an ethnic group who has long been persecuted by the Taliban.[16] The statue was blown up in accordance with the group’s rhetoric about the display of non-Islamic iconography. This incident is reminiscent of the damage done to the Bamiyan statues in 2001.

Looting and Illegal trade of artefacts[edit]

The Looting of historical artefacts and subsequent illegal trade has been a practice in Afghanistan for decades in almost every area of the country.[10]: 13 This has threatened archaeological heritage and cultural sites. One reason for why looting is such a significant venture for locals is a lack of cultural education and a feeling of disconnect with the land as a result of civil unrest. [17]: 13 Civil war in Afghanistan in the early 1990s also left many impoverished Afghans to turn to illegal trading for financial stability, as the country suffered economically and the international demand for authentic Afghan artefacts sky rocketed. [18]: 206 By 1998, almost 70% of the treasures stored in the National Museum of Afghanistan had been stolen and sold on.[19] : 20 Much of the damage inflicted to archaeological sites continue to occur during the search for equitable artefacts.[20] : 347

There have been initiatives in the past to try and remove artefacts form harms way and avoid instances of looting during tumultuous periods of time in the country. The Bactrian Gold also known as the Tillya Tepe, is a collection of famous gold articles from the first century AD. [21] : 12 In the 1980s these pieces were moved by museum staff to the Presidential Palace (also known as the Arg, Kabul)and placed in secure vaults to protect them from damage. [19]: 20 In 2003 the collection was reinstated again. [19]: 20 Another example of this kind of proactive response occurred just days before the Taliban’s first occupation in 1996. [19]: 20 The Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan’s Culture (SPACH) collaborated with employees at the National museum of Afghanistan to gather approximately 30% of artefacts dated before 1992. [22] These relics were packed and transported to the Hotel Inter-Continental Kabul, historically a safe house for foreigners and used by United Nations staff. This move was to protect ancient artefacts from Taliban interference and avoid any damage caused by the museum building’s continuous dilapidation. Despite the Taliban’s public destruction of cultural sites such as the Bamiyan Buddhas, looting actually increased after the Taliban was dispelled from authority in 2001.[20] This could be due to the severe punishment inflicted on those found guilty of the crime.[18]: 206

Common practice is for artefacts to be transported to Pakistan where they are sold to tourists and other interested buyers. Despite Pakistan’s 1975 Antiquities Act, prohibiting the commercial trade of objects that are over 75 years old, transactions still take place.[4]: 10 From Pakistan, treasures can be exported all over the world. Stolen items have been found on their way to Russia, China, the UK, and so far as Japan. [19]: 37 Artefacts rarely return to Afghanistan museums and safeholds. SPACH has in the past been able to reposes very few stolen and traded artefacts, all at a very high asking price. On the 23rd of April, 1997, ten relics originally belonging to the National Museum of Afghanistan were bought from a group of Pakistani traders carrying out business in Peshawar. [22] These articles ranged dated from medallions from approximately the 2nd century AD, and the Bronze Age. [22] These negotiations can be arduous and difficult to secure, dragging on for years.

International support and UNESCO involvement[edit]

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), immediately moved to aid in the reconstruction and rehabilitation of various Afghan cultural heritage sites after the Taliban lost control in 2001.[11]: vii One of UNESCO’s most famous projects in Afghanistan was the safeguard and rehabilitation of The Bamiyan Temples. Initially a team from UNESCO was sent to the site to review the ruins just after the collapse and stabilise the site as best they could. [11]: 64 In July 2002 a second party was sent, in conjunction with the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), and permanent surveillance of the site was established before work eventually started on the reconstruction and consolidation.[11]: 64 This site was placed on the World Heritage list in July 2003.[11]: 64 In total there has been significant international support for the restoration of various cultural sites in Afghanistan. Since 2005, UNESCO has organized over seven million dollars of pledge support from countries such as Japan, Italy, Switzerland, Germany, and America.[23]: 59 In addition to funding, UNESCO have supported the Afghan government as they endeavour to spread awareness about the importance of Afghanistan cultural heritage. Publishing and funding research papers and hosting cultural events are a few ways they continue to do this.[19]: 40

Artefacts of Religious diversity[edit]

Afghanistan is famous for its rich cultural and religious history. As a result of the country’s position on the Silk Road, Afghanistan has been home to many communities from all around Asia, Europe, and the Middle East.[1] It is a country that can date its human activity back to the Palaeolithic period (c. 30,000 BCE).[24] : 9 Although the current national religion is Islam, evidence of the existence of various religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Hellenism and Judaism can be found in archaeological sites across the country.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Droogan, Julian; Choat, Malcolm (15 September 2021). "The Taliban's rule threatens what's left of Afghanistan's dazzlingly diverse cultural history". The Conversation. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ Stark, Miriam T. (2005). Archaeology of Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 335. ISBN 978-1405102131.

- ^ "World's oldest oil paintings in Afghanistan". Reuters. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Ansari, Massoud (April 2002). "Plundering of Afghanistan". Archaeology. 55 (2): 18–20. JSTOR 41779651.

- ^ a b Allchin, Raymond (2019). Archaeology of Afghanistan: From Earliest Times to the Timurid Period. England: Edinburgh University Press.

- ^ a b c d "Excavations". Encyclopaedia Iranica. doi:10.1163/2330-4804_eiro_com_9386.

- ^ "Masson, Charles". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b Errington, Elizabeth Jane (2001). "Charles Masson and Begram". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 11 (1): 357–409. doi:10.3406/topoi.2001.1941.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan: Rediscovering the Past - Two Centuries of Archaeology". Center for Environmental Management of Military Lands. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b Cassar, Brendan; Rodríguez García, Ana Rosa (2006). "Chapter One: The Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage: an Overview of Activities since 1994". In van Krieken-Pieters, Juliette (ed.). Art and archaeology of Afghanistan : its fall and survival : a multi-disciplinary approach. Leiden: Brill. pp. 15–37. ISBN 978-9004151826.

- ^ a b c d e f g Margottini, Claudio (2015). After the Destruction of Giant Buddha Statues in Bamiyan (Afghanistan) In 2001 : A UNESCO's Emergency Activity for the Recovering and Rehabilitation of Cliff and Niches. New York: Springer Berlin / Heidelberg.

- ^ Brodie, Neil (December 2018). "Stolen history: looting and illicit trade". Museum International. 55 (3–4).

- ^ Reza 'Husseini', Said (April–June 2012). "Destruction of Bamiyan Buddhas Taliban Iconoclasm and Hazara Response". Himalayan and Central Asian Studies. 16 (2): 15–50.

- ^ a b c d Lawler, Andrew (13 August 2021). "The Taliban destroyed Afghanistan's ancient treasures. Will history repeat itself?". National Geographic: History. Photographs by Robert Nickelsberg. Archived from the original on 29 March 2022.

- ^ Steinbuch, Yaron. "Taliban destroy statue of foe, stoking fears after moderation claims". New York Post. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Ditmars, Hadani. "With Taliban Forces in Control, Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage Faces Renewed Threats". Architectural Digest. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Mairs, Rachel (2014). The Hellenistic Far East: Archeology, language and Identity in Greek Central Aisia. California: University of California Press.

- ^ a b van Krieken-Pieters, Juliette (2006). "Chapter Thirteen: Dilemmas in the Cultural Heritage Field: The Afghan Case and the Lessons for the Future". In van Krieken-Pieters, Juliette (ed.). Art and archaeology of Afghanistan : its fall and survival : a multi-disciplinary approach. Leiden: Brill. p. 206. ISBN 978-9004151826.

- ^ a b c d e f Cassar, Brendan; Noshadi, Sara; Ashraf Ghani, Mohammad (2015). Keeping history alive: safeguarding cultural heritage in post-conflict Afghanistan. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

- ^ a b Brodie, Neil; Renfrew, Colin (2005). "Looting and the World's Archaeological Heritage: The Inadequate Response". Annual Review of Anthropology. 34: 343–361. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ^ Pugachenkova, G.A.; Rempel, L.I. (1991). "Gold from Tillia-pepe". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. 5: 11–25.

- ^ a b c Dupree, Nancy Hatch. "Museum Under Siege: The Plunder Continues". Archaeology Archive. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ^ Manhart, Christian (2006). "Chapter Three: UNESCO's Rehabilitation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage: Mandate and Recent Activities". In van Krieken-Pieters, Juliette (ed.). Art and archaeology of Afghanistan : its fall and survival : a multi-disciplinary approach. Leiden: Brill. pp. 49–60. ISBN 978-9004151826.

- ^ Lee, Jonathan (2014). Amazing wonders of Afghanistan. Kabul: Rahmat.