Assault on Precinct 13 (1976 film)

- For the 2005 remake, see Assault on Precinct 13 (2005 film)

| Assault on Precinct 13 | |

|---|---|

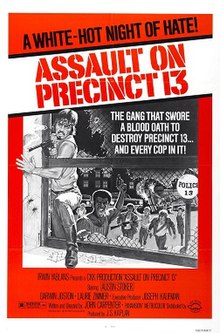

Original theatrical promotional poster, 2nd version[1] | |

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by | John Carpenter |

| Produced by | J. S. Kaplan |

| Starring | Austin Stoker Darwin Joston Laurie Zimmer |

| Cinematography | Douglas Knapp |

| Edited by | John T. Chance |

| Music by | John Carpenter |

Production company | CKK Corporation |

| Distributed by | Turtle Releasing |

Release date | November 5, 1976 |

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$100,000[2][3] |

Assault on Precinct 13 is a 1976 American action-thriller film written and directed by John Carpenter. It stars Austin Stoker as a law-enforcement officer who defends a defunct police precinct against an attack by a criminal gang, along with Darwin Joston as a convicted murderer who helps him. The story was inspired by the Howard Hawks western film Rio Bravo and the George A. Romero horror film Night of the Living Dead.

The film received mixed reviews with an unimpressive box-office return in the United States, but it won critical and popular acclaim in Europe. A remake appeared in 2005, directed by Jean-Francois Richet and starring Ethan Hawke and Laurence Fishburne.

Plot

The story takes place on a Saturday in Anderson, a crime-infested ghetto in South Central Los Angeles. Members of a local gang, called 'Street Thunder', have recently stolen a large number of automatic rifles and pistols. The film begins the night before, as a team of heavily armed LAPD officers ambush and kill several members of the gang. In the morning, the gang's warlords swear a blood oath of revenge, known as a "Cholo", against the police and the citizens of Los Angeles.

During the day, three sequences of events occur in parallel in and around Anderson: First, Lieutenant Ethan Bishop (Stoker), a newly promoted CHP officer, is assigned to command the old Anderson police precinct during the last few hours before it is permanently closed. The station is manned by a skeleton staff composed of one officer, Sergeant Chaney (Brandon), and the station's two secretaries, Leigh (Zimmer) and Julie (Loomis). Second, a member of Street Thunder shoots and kills a little girl and the driver of an ice-cream truck. The girl's father, Lawson, pursues and kills the hoodlum, whose fellow gang members chase the man into the Anderson precinct. In shock, he is unable to communicate to the officers what has happened to him. Third, a prison bus commanded by Starker (Cyphers) stops at the station to find medical help for one of the three prisoners being transported. The prisoners are Napoleon Wilson (Joston), a convicted violent killer on his way to Death Row, Wells (Burton), and Caudell, who is sick.

As the prisoners are put into jail cells, the telephone lines go dead, and when Starker prepares to put the prisoners back on the bus, the gang opens fire on the precinct, using weapons fitted with silencers. In seconds, they kill Chaney, the bus driver, Caudell, Starker, and the two officers with Starker. Bishop unchains Wilson from Starker's body and puts Wilson and Wells back into the cells. When the hoodlums cut the station's electricity and begin a second wave of shooting, Bishop sends Leigh to release Wells and Wilson, and they help Bishop and Leigh defend the station. Julie is killed in the firefight, and Wells is killed after being chosen to sneak out of the precinct through the sewer line. Meanwhile, the gang members remove all evidence of the skirmish in order to avoid attracting outside attention. Bishop hopes that someone has heard the unsilenced police weapons firing, but the neighborhood is too sparsely populated for nearby residents to pinpoint the location of the noise.

As the gang rallies for a third assault, Wilson, Leigh, and Bishop retreat to the basement, taking the still-catatonic Lawson with them. The story's climax occurs when the gang rushes into the station and Bishop shoots a tank full of acetylene gas, which explodes violently, killing the hoodlums in the basement. Finally, two police officers in a cruiser radio for backup after discovering the dead body of a telephone repairman hanging from a pole. When more police officers arrive and secure the station, the only survivors are Bishop, Leigh, Wilson, and Lawson.

Cast

- Austin Stoker as Ethan Bishop

- Darwin Joston as Napoleon Wilson

- Laurie Zimmer as Leigh

- Martin West as Lawson

- Tony Burton as Wells

- Charles Cyphers as Starker

- Nancy Kyes as Julie

- Peter Bruni as Ice Cream Man

- John J. Fox as Warden

- Marc Ross as Patrolman Tramer

- Alan Koss as Patrolman Baxter

- Henry Brandon as Chaney

- Kim Richards as Kathy Lawson

- John Carpenter as Gang member

Production

Development

After Dark Star failed to secure a directing career for Carpenter, an investor from Philadelphia, the CKK Corporation, took a gamble on Carpenter and put up the money for a new explotiation film he was planning and gave him a free rein to make any kind of picture he desired. Carpenter had hoped to make a Howard Hawks-style western like El Dorado or Rio Lobo, but when the $100,000 budget prohibited it, Carpenter refashioned the basic scenario of Rio Bravo into a modern setting.[2]

As with most of Carpenter's antagonists, Street Thunder is portrayed as a force that possesses mysterious origins and almost supernatural qualities. The gang members are not humanized and are instead represented as though they were zombies or ghouls since none of them have any dialogue, and Carpenter has acknowledged the influence of George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead on his portrayal of the gang.[4]

Screenplay

Carpenter joked "The script came together fast, some would say too fast."[4] Carpenter spiced the screenplay with a variety of in-jokes. For example, the character named "Leigh", played by Laurie Zimmer, was a reference to Rio Bravo scribe Leigh Brackett.[5] The day and time titles were used to make the film feel more like a documentary.[3]

The running gag of having Napoleon Wilson constantly ask "Gotta' smoke?" was inspired by the cigarette gags used in Howard Hawks's westerns.[3]

Casting

Carpenter assembled a main cast that consisted mostly of experienced but relatively obscure actors. The two leads were Austin Stoker, who had appeared previously in Battle for the Planet of the Apes and Sheba, Baby, and Darwin Joston, who had worked primarily in television and was also Carpenter's next-door neighbor.[4] After an open casting call, Carpenter added Charles Cyphers and Nancy Loomis to the cast.[2]

Behind the scenes, Carpenter continued to work with art director Tommy Wallace, property master Craig Stearns, and script supervisor (and future girlfriend) Debra Hill.[2] Carpenter also hired Douglas Knapp, a fellow USC student, to be cinematographer.[3]

Principal photography

Working within the limitations of a $100,000 budget, the film was shot in only 20 days in 1975.[3][6] The film was shot on 35mm Panavision in a 2.35:1 aspect ratio.[7] This film was the first time Carpenter used Panavision cameras and lenses for a film.[3] The interiors of the police station were shot on the now-defunct Producers Studios set while the exterior shots were of Venice Police station.[4] According to Carpenter, Zimmer "hated herself" after seeing her performance in the dailies while he thought she did "a great job."[4] Carpenter refers to this film as the most fun he has ever had directing.[8]

The first scene, in which several gang members of Street Thunder are gunned down by cops, was shot at USC. The gang members were USC students who, Carpenter said, had a lot of fun finding ways of dying while spilling blood over themselves.[3]

Post-production

Carpenter also edited the film using the pseudonym John T. Chance, the name of John Wayne's character in Rio Bravo. Carpenter also employed the John T. Chance pseudonym for his original version of The Anderson Alamo script, but he used his own name for the writing credit on the completed film.[9] Carpenter has said that the trick with shooting a low-budget film is to shoot as little footage as possible and extend the scenes for as long as one can.[3]

According to Carpenter, the editing process was very bare bones. One mistake Carpenter was not proud of was one shot "cut out of frame," which means the cut is made within the frame so a viewer can see it. Assault was shot on Panavision, which takes up the entire negative, and edited on Moviola, which cannot show the whole image, so if a cut was made improperly (i.e., frame line not lined up properly) then one would cut a half of a sprocket into the film and "cut out of frame," as happened to Carpenter. In the end, it did not matter because he said "It was so dark no one could see it, thank God!"[4]

Distribution

Although the film's title is Assault on Precinct 13, the action mainly takes place in a police station referred to as Precinct 9, Division 13, by Bishop's staff sergeant over the radio. The film's distributor was responsible for the misnomer. Carpenter originally called the film The Anderson Alamo before briefly changing the title to The Siege. During post-production, however, the distributor rejected Carpenter's title in favor of the film's present name (The Siege was later used as the title of another very controversial film, a 1998 drama about terrorist attacks in the U.S.). The moniker "Precinct 13" was used in order to give the new title a more ominous tone.[9]

The most infamous scene in the movie is the one in which a gang member deliberately shoots and kills a little girl standing near an ice-cream truck. The MPAA threatened to give the film an X-rating if the scene was not cut. Following the advice of his distributor, Carpenter gave the appearance of complying by cutting the scene from the copy he gave to the MPAA, but he distributed the film with the "ice cream truck" scene intact.[4]

For reasons unknown, the German title of the original theatrical release was "Das Ende" ("The End"), a title unrelated to the movie's content.[6]

Reception

Release

The film was originally released in the United States in 1976 to mixed critical reviews and unimpressive box office earnings. The following year, however, it was screened at the 21st London Film Festival, where it was one of the festival's best-received films and garnered tremendous critical and popular acclaim.[citation needed] The overwhelmingly positive British response to the film led to its critical and commercial success throughout Europe.[citation needed] Subsequently, the film underwent a reassessment by American critics and audiences, and it is now generally considered one of the best action films of the 1970s.[citation needed] John Carpenter has said that the British audiences immediately understood and enjoyed the film's similarities to American westerns, whereas American audiences were too familiar with the western genre to fully appreciate the movie at first.[4][8]

Critical response

Jeffrey Wells of Films In Review wrote, "Skillfully paced and edited, Assault was rich with Hawksian dialogue and humor, especially in the clever caricature of the classic 'Hawks woman' by Laurie Zimmer."[10] In his book The Horror Films of the 1970s, John Kenneth Muir gave the film three and a half stars, calling it "a lean, mean exciting horror motion picture... a movie of ingenuity, cunning and thrills."[11] Leonard Maltin, who also gave it three and a half stars, calls the film a "knockout."[12] Brian Lindsey of Eccentric Cinema gave the film 6 out of a scale of 10, saying the film "isn't believable for a second — yet this doesn't stop it from being a fun little B picture in the best drive-in tradition."[13]

Assault currently has a 96% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[14]

Legacy

Assault on Precinct 13 is now considered by many to be one of the most underrated action films of the 1970s. Premiere put Assault on its list of 50 Unsung Classics in the July 1999 issue.[15] As a result of this film, Donald Pleasence would go on to star in Carpenter's Halloween, as his daughters were big fans of Assault.[16] Film historian David Thomson described Assault as "a Hawksian set of a police station besieged by hoodlums - economical, tense, beautiful and highly arousing. It fulfills all Carpenter's ambitions for gripping the audience emotionally and never letting go."[17]

Film director Edgar Wright and actor Simon Pegg are big fans of Assault. "You wouldn't really call it an action film," claims Pegg, "because it was pre- the evolution of that kind of film. And yet it is kind of an action film in a way." "It's very much his [Carpenter's] kind of urban western", adds Wright, "in the way it is staging Rio Bravo set up in downtown 70s LA... And the other thing is, for a low budget film particularly, it looks great."[18]

In 2002, the film inspired Florent Emilio Siri's 2002 quasi-remake The Nest,[19][20] and three years later Assault was remade in by director Jean-Francois Richet. The Richet remake has been praised by some as an expertly made B-movie, and dismissed by others as formulaic.[21]

Critics and commentators have often described Assault as a cross between Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo and George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead.[11][13][22] Carpenter acknowledges the influence of both films.[3][4]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

One of the film's distinctive features is its score, composed and recorded by Carpenter. The combination of synthesizer hooks, electronic drones and drum machines sets it apart from many other scores of the period and creates a distinct style of minimalist electronic soundtrack with which Carpenter, and his films, would become associated. The score consists of two main themes: the main title theme, with its familiar synthesizer melody, and a slower contemplative theme used in the film's more subdued scenes. The main theme was partially inspired by both Lalo Schifrin's score to Dirty Harry and Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song". Besides these two themes the soundtrack also features a series of ominous drones and primal drum patterns which often represent the anonymous gang gathering in the shadows. The theme tune would be somewhat reworked in 1986 as an Italo-disco 12",[23] and more famously as the 1990 UK-charting rave-song Hardcore Uproar.[24] Carpenter made roughly three to five separate pieces of music and edited them to the film as appropriate.[4]

Carpenter had several banks of synthesizers that would each have to be reset when another sound had to be created, taking a great deal of time.[3] He was assisted by Dan Wyman in creating the musical score.[5] The score was written in three days.[4]

Beyond its use in the film, the score is often cited as an influence on various electronic and hip hop artists with its main title theme being sampled by artists including Afrika Bambaataa, Tricky, Dead Prez and Bomb the Bass.[25]

Despite this influence, except for a few compilation appearances, the film's score remained available only in bootleg form until 2003 when it was given an official release through the French label, Record Makers.[25] In early 2004, Piers Martin of NME wrote that Carpenter's minimalist synthesizer score accounted for much of the film's tense and menacing atmosphere and its "impact, 27 years on, is still being felt."[26]

Track listing

- "Assault On Precinct 13 (Main Title)"

- "Napoleon Wilson"

- "Street Thunder"

- "Precinct 9 - Division 13"

- "Targets / Ice Cream Man On Edge"

- "Wrong Flavour"

- "Emergency Stop"

- "Lawson's Revenge"

- "Sanctuary"

- "Second Wave"

- "The Windows!"

- "Julie"

- "Well's Flight"

- "To The Basement"

- "Walking Out"

- "Assault On Precinct 13"

Home video releases

Assault on Precinct 13 was released on DVD on March 11, 2003 in a widescreen "Special Edition" release.[27] Brian Lindsay of Eccentric Cinema gave this DVD release 10 out of 10, the website's highest rating.[13] Special features include:

- Q & A interview session with writer/director John Carpenter and actor Austin Stoker at American Cinematheque's 2002 John Carpenter retrospective

- Original theatrical trailer

- 2 radio spots

- Behind-the-scenes and lobby card stills gallery

- Full-length audio commentary by writer/director John Carpenter. The audio commentary was ported from a mid-90s Laserdisc release.[13]

- Isolated music score

The film is available on both DVD and Blu-ray Disc as a "Restored Collector's Edition" in 2008 and 2009, respectively. Both releases have all of the special features found on the previous "Special Edition" DVD.[28][29]

See also

- List of American films of 1976

- The Nest (Nid de guêpes)

References

Notes

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 - Poster #2". IMP Awards. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ a b c d Muir, p. 10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Carpenter, John (writer/director). (2003). Audio Commentary on Assault on Precinct 13 by John Carpenter. [DVD]. Image Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Q & A session with John Carpenter and Austin Stoker at American Cinematheque's 2002 John Carpenter retrospective, in the 2003 special edition Region 1 DVD of Assault on Precinct 13.

- ^ a b Muir, p. 11

- ^ a b "Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) - Trivia". IMDb. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) - Technical specifications". IMDb. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ a b Muir, p. 12

- ^ a b Still Gallery feature, included in the 2003 special edition Region 1 DVD of Assault on Precinct 13.

- ^ Wells, Jeffrey (April 1980). "New Fright Master John Carpenter". Films In Review: p. 218.

- ^ a b Muir, John Kenneth. The Horror Films of the 1970s (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: McFarland and Company Inc. pp. 376-379. ISBN 0-7864-1249-6.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (August 2008). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide (2009 ed.). New York, NY: Penquin Group. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ a b c d Lindsey, Brian (April 6th, 2003). "ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976)". Eccentric Cinema. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ "Premiere - 100 Most Daring Movies & 50 Unsung Classics". Combustible Celluloid. (Reprinted from October 1998 & July 1999 issues of Premiere). Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Muir, p. 13

- ^ Thomson, David (October 26, 2010). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Fifth Edition, Completely Updated and Expanded (Hardcover ed.). Knopf. p. 155. ISBN 978-0307271747.

- ^ Pegg, Simon & Wright, Edgar (hosts). (2007). The Classic Cult Film Festival: Assault On Precinct 13

- ^ MSN Movies. The Nest: Critics' Review by Jeremy Wheeler

- ^ All Movie Guide for Assault on Precinct 13

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Corilss, Richard (January 16th, 2005). "Movies: Repeat Assault, with Vigor". Time. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Listen to John Carpenter's The End, the 1986 reworked theme to Assault on Precinct 13

- ^ Listen to Hardcore Uproar, a 1990 hit based on the theme tune to Assault on Precinct 13 by Together

- ^ a b "Assault on Precinct 13 Soundtrack" (in French). Record Makers. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Martin, Piers (January 10, 2004). "John Carpenter Assault on Precinct 13 Soundtrack". NME.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2003 Special Edition DVD) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (Restored Collector's Edition DVD) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (Restored Collector's Edition Blu-ray) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

Bibliography

- Muir, John Kenneth (2000). The Films of John Carpenter (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: McFarland and Company Inc. ISBN 0-7864-0725-5.

External links

- Assault on Precinct 13 at IMDb

- Assault on Precinct 13 at AllMovie

- Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) on the Official John Carpenter website

- Assault on Precinct 13 Trailer on YouTube

- Listen to the original soundtrack for Assault on Precinct 13