Axis mundi

The axis mundi (also cosmic axis, world axis, world pillar, center of the world, world tree), in certain beliefs and philosophies, is the world center, or the connection between Heaven and Earth. As the celestial pole and geographic pole, it expresses a point of connection between sky and earth where the four compass directions meet. At this point travel and correspondence is made between higher and lower realms.[1] Communication from lower realms may ascend to higher ones and blessings from higher realms may descend to lower ones and be disseminated to all.[2] The spot functions as the omphalos (navel), the world's point of beginning.[3][4][5]

The image relates to the center of the earth (perhaps like an umbilical providing nourishment)[citation needed]. It may have the form of a natural object (a mountain, a tree, a vine, a stalk, a column of smoke or fire) or a product of human manufacture (a staff, a tower, a ladder, a staircase, a maypole, a cross, a steeple, a rope, a totem pole, a pillar, a spire). Its proximity to heaven may carry implications that are chiefly religious (pagoda, temple mount, minaret, church) or secular (obelisk, lighthouse, rocket, skyscraper). The image appears in religious and secular contexts.[6] The axis mundi symbol may be found in cultures utilizing shamanic practices or animist belief systems, in major world religions, and in technologically advanced "urban centers". In Mircea Eliade's opinion, "Every Microcosm, every inhabited region, has a Centre; that is to say, a place that is sacred above all."[7] The axis mundi is often associated with mandalas.[citation needed]

Background

The symbol originates in a natural and universal psychological perception: that the spot one occupies stands at "the center of the world". This space serves as a microcosm of order because it is known and settled. Outside the boundaries of the microcosm lie foreign realms that, because they are unfamiliar or not ordered, represent chaos, death or night.[8] From the center one may still venture in any of the four cardinal directions, make discoveries, and establish new centers as new realms become known and settled. The name of China, meaning "Middle Nation" (中国 pinyin: Zhōngguó), is often interpreted as an expression of an ancient perception that the Chinese polity (or group of polities) occupied the center of the world, with other lands lying in various directions relative to it.[6]

Within the central known universe a specific locale-often a mountain or other elevated place, a spot where earth and sky come closest gains status as center of the center, the axis mundi. High mountains are typically regarded as sacred by peoples living near them. Shrines are often erected at the summit or base.[9] Mount Kunlun fills a similar role in China.[10] For the ancient Hebrews Mount Zion expressed the symbol.[citation needed] Sioux beliefs take the Black Hills as the axis mundi.[citation needed] Mount Kailash is holy to Hinduism and several religions in Tibet. The Pitjantjatjara people in central Australia consider Uluru to be central to both their world and culture. In ancient Mesopotamia the cultures of ancient Sumer and Babylon erected artificial mountains, or ziggurats, on the flat river plain. These supported staircases leading to temples at the top. The Hindu temples in India are often situated on high mountains. E.g. Amarnath, Tirupati, Vaishno Devi etc. The pre-Columbian residents of Teotihuacán in Mexico erected huge pyramids featuring staircases leading to heaven. These Amerindian temples were often placed on top of caves or subterranean springs, which were thought to be openings to the underworld.[11] Jacob's Ladder is an axis mundi image, as is the Temple Mount. For Christians the Cross on Mount Calvary expresses the symbol.[12] The Middle Kingdom, China, had a central mountain, Kunlun, known in Taoist literature as "the mountain at the middle of the world." To "go into the mountains" meant to dedicate oneself to a spiritual life.[13] Monasteries of all faiths tend, like shrines, to be placed at elevated spots. Wise religious teachers are typically depicted in literature and art as bringing their revelations at world centers: mountains, trees, temples.

Because the axis mundi is an idea that unites a number of concrete images, no contradiction exists in regarding multiple spots as "the center of the world". The symbol can operate in a number of locales at once.[7] Mount Hermon was regarded as the axis mundi in Caananite tradition, from where the sons of God are introduced descending in 1 Enoch (1En6:6).[14] The ancient Armenians had a number of holy sites, the most important of which was Mount Ararat, which was thought to be the home of the gods as well as the center of the Universe.[15] Likewise, the ancient Greeks regarded several sites as places of earth's omphalos (navel) stone, notably the oracle at Delphi, while still maintaining a belief in a cosmic world tree and in Mount Olympus as the abode of the gods. Judaism has the Temple Mount, Christianity has the Mount of Olives and Calvary, Islam has Ka'aba, said to be the first building on earth, and the Temple Mount (Dome of the Rock). In Hinduism, Mount Kailash is identified with the mythical Mount Meru and regarded as the home of Shiva; in Vajrayana Buddhism, Mount Kailash is recognized as the most sacred place where all the dragon currents converge and is regarded as the gateway to Shambhala. In Shinto, the Ise Shrine is the omphalos.[citation needed] In addition to the Kunlun Mountains, where it is believed the peach tree of immortality is located, the Chinese folk religion recognizes four other specific mountains as pillars of the world.

Sacred places constitute world centers (omphalos) with the altar or place of prayer as the axis. Altars, incense sticks, candles and torches form the axis by sending a column of smoke, and prayer, toward heaven. The architecture of sacred places often reflects this role. "Every temple or palace--and by extension, every sacred city or royal residence--is a Sacred Mountain, thus becoming a Centre."[16] The stupa of Hinduism, and later Buddhism, reflects Mount Meru. Cathedrals are laid out in the form of a cross, with the vertical bar representing the union of earth and heaven as the horizontal bars represent union of people to one another, with the altar at the intersection. Pagoda structures in Asian temples take the form of a stairway linking earth and heaven. A steeple in a church or a minaret in a mosque also serve as connections of earth and heaven. Structures such as the maypole, derived from the Saxons' Irminsul, and the totem pole among indigenous peoples of the Americas also represent world axes. The calumet, or sacred pipe, represents a column of smoke (the soul) rising form a world center.[17] A mandala creates a world center within the boundaries of its two-dimensional space analogous to that created in three-dimensional space by a shrine.[18]

Plants

Plants often serve as images of the axis mundi. The image of the Cosmic Tree provides an axis symbol that unites three planes: sky (branches), earth (trunk) and underworld (roots).[19] In some Pacific island cultures the banyan tree, of which the Bodhi tree is of the Sacred Fig variety, is the abode of ancestor spirits. In Hindu religion, the banyan tree is considered sacred and is called ashwath vriksha ("I am banyan tree among trees" - Bhagavad Gita). It represents eternal life because of its seemingly ever-expanding branches. The Bodhi tree is also the name given to the tree under which Gautama Siddhartha, the historical Buddha, sat on the night he attained enlightenment. The Yggdrasil, or World Ash, functions in much the same way in Norse mythology; it is the site where Odin found enlightenment. Other examples include Jievaras in Lithuanian mythology and Thor's Oak in the myths of the pre-Christian Germanic peoples. The Tree of Life and the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil in Genesis present two aspects of the same image. Each is said to stand at the center of the Paradise garden from which four rivers flow to nourish the whole world. Each tree confers a boon. Bamboo, the plant from which Asian calligraphy pens are made, represents knowledge and is regularly found on Asian college campuses. The Christmas tree, which can be traced in its origins back to pre-Christian European beliefs, represents an axis mundi.[20] Entheogens (psychoactive substances) are often[who?] regarded as world axes[clarify], such as the Fly Agaric mushroom among the Evenks of Russia.[citation needed] In China, traditional cosmography sometimes depicts the world center marked with the Jian tree (建木). Two more trees are placed at the East and West, corresponding to the points of sunrise and sunset, as described in the Huainanzi. The Mesoamerican world tree connects the planes of the Underworld and the sky with that of the terrestrial realm.[21]

Human figure

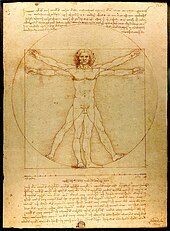

The human body can express the symbol of world axis.[22] Some of the more abstract Tree of Life representations, such as the sefirot in Kabbalism and in the chakra system recognized by Hinduism and Buddhism, merge with the concept of the human body as a pillar between heaven and earth. Disciplines such as yoga and tai chi begin from the premise of the human body as axis mundi. The Buddha represents a world centre in human form.[23] Large statues of a meditating figure unite the human figure with the symbolism of temple and tower. Astrology in all its forms assumes a connection between human health and affairs and the orientation of these with celestial bodies. World religions regard the body itself as a temple and prayer as a column uniting earth to heaven. The ancient Colossus of Rhodes combined the role of human figure with those of portal and skyscraper. The image of a human being suspended on a tree or a cross locates the figure at the axis where heaven and earth meet. The Renaissance image known as the Vitruvian Man represented a symbolic and mathematical exploration of the human form as world axis.[20]

Homes

Homes can represent world centers. The symbolism for their residents is the same as for inhabitants of palaces and other sacred mountains.[16] The hearth participates in the symbolism of the altar and a central garden participates in the symbolism of primordial paradise. In Asian cultures houses were traditionally laid out in the form of a square oriented toward the four compass directions. A traditional Asian home was oriented toward the sky through feng shui, a system of geomancy, just as a palace would be. Traditional Arab houses are also laid out as a square surrounding a central fountain that evokes a primordial garden paradise. Mircea Eliade noted that "the symbolism of the pillar in [European] peasant houses likewise derives from the 'symbolic field' of the axis mundi. In many archaic dwellings the central pillar does in fact serve as a means of communication with the heavens, with the sky."[24] The nomadic peoples of Mongolia and the Americas more often lived in circular structures. The central pole of the tent still operated as an axis but a fixed reference to the four compass points was avoided.[25]

Shamanic function

A common shamanic concept, and a universally told story, is that of the healer traversing the axis mundi to bring back knowledge from the other world. It may be seen in the stories from Odin and the World Ash Tree to the Garden of Eden and Jacob's Ladder to Jack and the Beanstalk and Rapunzel. It is the essence of the journey described in The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri. The epic poem relates its hero's descent and ascent through a series of spiral structures that take him from through the core of the earth, from the depths of Hell to celestial Paradise. It is also a central tenet in the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex.[26]

Anyone or anything suspended on the axis between heaven and earth becomes a repository of potential knowledge. A special status accrues to the thing suspended: a serpent, a victim of crucifixion or hanging, a rod, a fruit, mistletoe. Derivations of this idea find form in the Rod of Asclepius, an emblem of the medical profession, and in the caduceus, an emblem of correspondence and commercial professions. The staff in these emblems represents the axis mundi while the serpents act as guardians of, or guides to, knowledge.[27]

Traditional expressions

Asia

- Wuji

- Bodhi tree, especially where Gautama Buddha found Enlightenment

- Eight Pillars: eight axes mundi in Chinese mythology

- Pagoda

- Stupa in Buddhism

- Mount Meru in Hinduism and Buddhism

- Mount Kailash regarded by Hinduism and several religions in Tibet, e.g. Bön

- Jambudvipa in Hinduism and Jainism which is regarded as the actual navel of the universe (which is human in form)

- Kailasa (India), the abode of Shiva

- Mandara (India)

- Shiva Lingam (India)

- Kunlun Mountain (China), residence of the Immortals and the site of a peach tree offering immortality

- Human figure (yoga, tai chi, Buddha in meditation, sacred images)

- Ise Shrine (Shinto)

- Central courtyard in traditional home

- Bamboo stalk, associated with knowledge and learning

- Mago Stronghold (Old Korea) also known as Mago-seong, Mago San-seong, Go-Seong, Halmi-seong. Primordial Home of the Great Goddess and HER primordial descendants[28]

Middle East

- Garden of Eden with four rivers

- Tree of Life and Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil

- Mt. Ararat landing place of Noah's ark

- Ziggurat, or Tower of Babel

- Jacob's Ladder

- Jerusalem, specifically, the Holy Temple; focus of Jewish prayer where Abraham bound Isaac

- Cross of the Crucifixion

- Steeple

- Ka'aba in Mecca; focus of Muslim prayer

- Qutb, In Sufism, an intermediary figure between God and mankind

- Dome of the Rock where Muhammad, in Islam, is believed to have ascended to heaven

- Minaret

- Dilmun

- Garizim (Samaria)

- Hara Berezaiti (Persia)

- Zaphon

Africa

- Meskel bonfire

- Stelae of the Aksumite Empire

- Pyramids of Egypt

- Osun-Osogbo Sacred Grove of Nigeria

- Jebel Barkal of Sudan

- Idafe Rock of prehispanic La Palma

- Mt Kenya of Kenya

- Mount Kilimanjaro

Europe

- Yggdrasil (the world ash-tree in Norse cosmology)

- Irminsul (the great pillar in Germanic paganism)

- Hill of Uisneach (the navel and center of Ireland in Irish mythology)[29]

- Mount Olympus in Greece, court of the gods (Greek mythology)

- Sampo or Sammas (Baltic-Finnic mythology)

- Delphi, home of the Oracle of Delphi (Greek mythology)

- Colossus of Rhodes (Greek mythology)

- Maypole (East Europe and Germanic paganism)

- Jack's Beanstalk (English fairy tale)

- Rapunzel's Tower (German fairy tale)

- Hearth

- Central pillar of peasant homes

- Altar

- Vitruvian Man

- Hagia Sophia

- St. Peter's Basilica

- Umbilicus urbis Romae, a structure in the Roman Forum from where all the Roman roads parted.

- Isle of Man (Emain Ablach, the gate to the Otherworld in Irish Mythology)

The Americas

- Teotihuacán Pyramids

- Totem Pole

- Tent

- Black Hills (Sioux)

- Calumet (sacred pipe)

- Sipapu (Hopi)

- Southeastern Ceremonial Complex

- Medicine wheels of the northern Great Plains

- Temple Lot (Mormonism)

- Cuzco (Incas), meaning "navel" in Quechua[citation needed]

- Chakana

- Mesoamerican world tree

- Lanzon

- Turtle Island

- Yvy marae, the sacred land "free from all evil", whose pursuit led to the colonization of lowland South America by the Tupí and Guaraní peoples, guided by the karai or priests[30][31][32]

Australia

Modern expressions

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (November 2008) |

Axis mundi symbolism continues to be evoked, even in modern societies, through various art forms and has a deep rooted spiritual inspiration that transcends time.

The idea has proven consequential in the realm of architecture. Structures that have a spiritual meaning, that inspire and create a connection between the spiritual world and the physical world, that are erected as monuments to commemorate are achievements can be considered to be inspired by the axis mundi. The pyramids that have been erected throughout human history serve as perfect examples of axis mundi. A skyscraper, as the term itself suggests, suggests the connection of earth and sky, as do spire structures of all sorts. Such buildings come to be regarded as "centers" of an inhabited area, or even the world, and serve as icons of its ideals.[33] The first skyscraper of modern times, the Eiffel Tower, exemplifies this role. The structure was erected in 1889 in Paris, France, to serve as the centerpiece for the Exposition Universelle, making it a symbolic world center from the planning stages. It has served as an iconic image for the city and the nation ever since.[34] Landmark skyscrapers often take names that clearly identify them as centers.[35]

Artistic representations of the axis mundi are plentiful. Just one example of these is the Colonne sans fin (The Endless Column, 1938) an abstract sculpture by Romanian Constantin Brâncuși. The column takes the form of a "sky pillar" (columna cerului) upholding the heavens even as its rhythmically repeating segments invite climb and suggest the possibility of ascension.[36]

Visual representation of the axis mundi in contemporary art is currently being achieved by photographer Jennifer Westjohn. By the process of mirror symmetry of a single photograph the artist exposes an entirely new image: the 5th point. The viewer is then introduced to a coalescing of nature and the universe which lends new perspective to the original image. This artistic representation of axis mundi opens the mind up to a new visual dimension both energistic and shamanic.[37]

Axis mundi symbolism exists in modern space travel. [38] Each astronaut embarks on a perilous journey into the heavens, per se, and if successful, returns with a boon for dissemination. The Apollo 13 insignia stated it succinctly: Ex luna scientia ("From the Moon, knowledge").[39]

See also

References

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.48-51

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.40

- ^ J. C. Cooper. An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Traditional Symbols. Thames and Hudson: New York, 1978. ISBN 0500271259.

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Willard Trask). 'Archetypes and Repetition' in The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton, 1971. ISBN 0691017778. p.16

- ^ Winther, Rasmus Grønfeldt (2014) World Navels. Cartouche 89: 15-21 http://philpapers.org/archive/WINWN.pdf

- ^ a b Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.61-63, 173-175

- ^ a b Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.39

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.37-39

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.41-43

- ^ Wang, Chong. Lunheng Part I: Philosophical Essays of Wang Ch'ung. Trans. Alfred Forke. London: Luzac & Co., 1907. p.337.

- ^ Bailey, Gauvin Alexander (2005). Art of Colonial Latin America. New York (NY): Phaidon Press Limited. p. 21.

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.680-685

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.681

- ^ Kelley Coblentz Bautch (25 September 2003). A Study of the Geography of 1 Enoch 17-19: "no One Has Seen what I Have Seen". BRILL. pp. 62–. ISBN 978-90-04-13103-3. Retrieved 28 June 2011.

- ^ http://www.peopleofar.com/2013/08/11/noahs-ark-in-the-mountains-of-armenia/

- ^ a b Mircea Eliade (tr. Willard Trask). 'Archetypes and Repetition' in The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton, 1971. ISBN 0691017778. p.12

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.148-149

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.52-54

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.42-45

- ^ a b Chevalier, Jean and Gheerbrandt, Alain. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.1025-1033

- ^ Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (1993). The Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 186. ISBN 0500050686.

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Symbolism of the Centre' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.54

- ^ Mircea Eliade (tr. Philip Mairet). 'Indian Symbolisms of Time and Eternity' in Images and Symbols. Princeton, 1991. ISBN 069102068X. p.76

- ^ Mircea Eliade. 'Brâncuși and Mythology' in Symbolism, the Sacred, and the Arts. Continuum, 1992. ISBN 0826406181. p. 100

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.529-531

- ^ Townsend, Richard F. (2004). Hero, Hawk, and Open Hand. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10601-7.

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp.142-145

- ^ Hwang, Helen Hye-Sook (2015). The Mago Way: Re-discovering Mago, the Great Goddess from East Asia. Mago Books. pp. 136–142. ISBN 9781516907922.

- ^ Alwyn and Brinley Rees. Celtic Heritage. Thames and Hudson: New York, 1961. ISBN 0500270392. pp. 159-161.

- ^ CASCUDO, L. C. Geografia dos mitos brasileiros. 3ª edição. São Paulo. Global. 2002. p. 133.

- ^ CLASTRES, P. Le grand parler. Paris: Éditions du seuil, '975. p. 9

- ^ http://www.tekoamboytyitarypu.site90.com/index.php?news&nid=9

- ^ Judith Dupré. 'Skyscrapers: A History of the World's Most Extraordinary Buildings.' Black Dog & Leventhal, 1998/2008. p.137

- ^ Judith Dupré. 'Skyscrapers: A History of the World's Most Extraordinary Buildings.' Black Dog & Leventhal, 1998/2008. p. 19

- ^ Judith Dupré. 'Skyscrapers: A History of the World's Most Extraordinary Buildings.' Black Dog & Leventhal, 1998/2008. pp. 45, 69, 81, 91, 97,135, 136, 143

- ^ Mircea Eliade. 'Brâncuși and Mythology' in Symbolism, the Sacred, and the Arts. Continuum, 1992. ISBN 0826406181. p.99-100

- ^ Jennifer Westjohn. Photographer. "jenniferwestjohn.com" "the5thpoint.com" 2013-2017

- ^ Jean Chevalier and Alain Gheerbrandt. A Dictionary of Symbols. Penguin Books: London, 1996. ISBN 0140512543. pp. 18, 1020-1022

- ^ Nasa Apollo Mission: Apollo 13. 2007-08-25