Battle of Vercellae

| Battle of Vercellae | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cimbrian War | |||||||

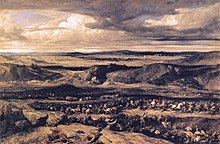

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, The battle of Vercellae, from the Ca' Dolfin Tiepolos, 1725-1729 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Cimbri | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Gaius Marius Quintus Lutatius Catulus Lucius Cornelius Sulla |

Boiorix † Lugius † Claodicus (POW) Caesorix (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 54,000 men (8 legions with cavalry and auxiliaries) | 120,000–180,000 warrior including 15,000 cavalry (400,000 including civilians) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,000 killed[1] |

160,000 killed (Livy) 140,000 killed (Orosius) 60,000 captured 120,000 killed (Plutarch) 60,000 captured 100,000 killed or captured (Paterculus) 65,000 killed (Florus) | ||||||

Roman victories.

Roman victories. Cimbri and Teutons victories.

Cimbri and Teutons victories.The Battle of Vercellae, or Battle of the Raudine Plain, was fought on 30 July 101 BC on a plain near Vercellae in Gallia Cisalpina (modern day Northern Italy). A Germanic-Celtic confederation under the command of the Cimbric king Boiorix was defeated by a Roman army under the joint command of the consul Gaius Marius and the proconsul Quintus Lutatius Catulus. The battle marked the end of the Germanic threat to the Roman Republic.[2][3]

Background

In 113 BC a large migrating Germanic-Celtic alliance headed by the Cimbri and the Teutones entered the Roman sphere of influence. They invaded Noricum which was inhabited by the Taurisci people, friends and allies of Rome. The Senate commissioned Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, one of the consuls, to lead a substantial Roman army to Noricum to force the barbarians out. An engagement, later called the battle of Noreia, took place, in which the invaders completely overwhelmed the Roman Legions and inflicted a devastating loss on them.[4]

After the Noreia victory, the Cimbri and Teutones moved westward towards Gaul. In 109 BC, they moved along the Rhodanus River towards the Roman province of Transalpine Gaul. The Roman consul, Marcus Junius Silanus, was sent to take care of the renewed Germanic threat. Silanus marched his army north along the Rhodanus River to confront the migrating Germanic tribes. He met the Cimbri approximately 100 miles north of Arausio where a battle was fought and the Romans suffered another humiliating defeat. The Germanic tribes then moved to the lands north and east of Tolosa in south-western Gaul.[5]

To the Romans, the presence of the Germanic tribes in Gaul posed a serious threat to the stability in the area and to their prestige. Lucius Cassius Longinus, one of the consuls of 107 BC, was sent to Gaul at the head of another large army. He first fought the Cimbri and their Gallic allies the Volcae Tectosages just outside Tolosa, and despite the huge number of tribesmen, the Romans routed them. Unfortunately for the Romans, a few days later they were ambushed while marching on Burdigala. The Battle of Burdigala destroyed the Romans' hopes of definitively defeating the Cimbri and so the Germanic threat continued.[6]

In 106 BC the Romans sent their largest army yet; the senior consul of that year, Quintus Servilius Caepio, was authorized to use eight legions in an effort to end the Germanic threat once and for all. While the Romans were busy getting their army together, the Volcae Tectosages had quarrelled with their Germanic guests, and had asked them to leave the area. When Caepio arrived he only found the local tribes and they sensibly decided not to fight the newly arrived legions. In 105 BC, Caepio's command was prorogued and a further six legions were raised in Rome by Gnaeus Mallius Maximus, one of the consuls of 105 BC. Mallius Maximus led them to reinforce Caepio who was near Arausio. Unfortunately for the Romans, Caepio who was a patrician, and Mallius Maximus, who was a 'new man', clashed with each other. Caepio refused to take orders from Mallius Maximus who as consul outranked him. All this led to a divided Roman force with the two armies so uncooperative that they were unwilling to support each other when the fighting started. Meanwhile, the Germanic tribes had combined their forces. First they attacked and defeated Caepio's army and then, with great confidence, took on Mallius Maximus's army and defeated it too. The Battle of Arausio was considered the greatest Roman defeat since the slaughter suffered at the Battle of Cannae during the Punic Wars.[7]

In 104 BC the Cimbri and the Teutones seemed to be heading for Italy. The Romans sent the senior consul of that year, Gaius Marius, a proven and capable general, at the head of another large army. The Germanic tribes never materialized so Marius subdued the Volcae Tectosages capturing their king Copillus.[8] In 103 BC, Sulla, one of Marius's lieutenants, succeeded in persuading the Germanic Marsi tribe to become friends and allies of Rome; they detached themselves from the Germanic confederation and went back to Germania.[9] In 102 BC Marius marched against the Teutones and Ambrones in Gaul. Quintus Lutatius Catulus, Marius's consular colleague, was tasked with keeping the Cimbri out of Italy. Catulus's army suffered some losses when the Cimbri attacked him near Tridentum, but he retreated and kept his army intact.[10] Meanwhile, Marius had completely defeated the Ambrones and the Teutones in a battle near Aquae Sextiae in Transalpine Gaul. In 101 BC the armies of Marius and Catulus joined forces and faced the Germanic invaders in Galia Cisalpina (Italian Gaul).[11]

Prelude

By July 101 BC the Cimbri were heading westwards along the banks of the Po River. Unfortunately for them, the armies of Marius and Catulus had merged and now camped around Placentia. Marius had been elected consul again (his fifth consulship) and was therefore in supreme command. He began negotiations with the Cimbri, who demanded land to settle on. Marius refused and instead sought to demoralize the Cimbri by parading captured Teuton nobles before them. Neither side genuinely sought negotiations, the Romans not intending to hand over their land to foreign invaders and the Cimbri believing themselves to be the superior force.[12][13]

Over the next few days the armies manoeuvred against each other, the Romans initially refusing to give battle. Eventually Marius chose the optimal location for the battle, an open plain (the Raudine Plain) near Vercellae, and then met with the Cimbri leader Boiorix to agree on the time and place of battle. Marius had some 52,000-54,000 men (mainly heavy infantry), the Cimbri had 120,000-180,000 warriors. (Modern historians are always somewhat sceptical about the overwhelming numbers the legions are reported to have fought, but there is no way to determine the true numbers today.)[14][15]

Location

Traditionally most historians locate the location of the battle in or near the modern Vercelli, Piedmont, in northern Italy. Some historians[16] think that "vercellae" is not a proper name and may refer to any mining area at the confluence of two rivers.

The latter historians think that the Cimbri followed the river Adige after having crossed the Brenner Pass, instead of "unreasonably" turning west to the modern Vercelli; this way, the location of the battle would be in the modern Polesine instead, possibly near the modern Rovigo. At Borgo Vercelli, near the river Sesia, 5 km from Vercelli, items have been found that supposedly strengthen the tradition.[citation needed]

Another suggested location is the hamlet of Roddi, in what is now the province of Cuneo, Piedmont.[17]

Battle

On 30 July 101 BC the opposing sides met on the Raudine Plain. The 15,000 strong Cimbric cavalry rode onto the battlefield. Behind them came the tens of thousands of infantry. According to Plutarch, Marius made a final sacrifice to the gods: "Marius washed his hands, and lifting them up to heaven, vowed to make a sacrifice of 100 beasts should victory be his".

Marius had split up his own army in two lots of 15,000 each forming the wings of the army. Catulus and his 24,000 less experienced troops formed the centre. Marius took command of the left wing, with Sulla commanding the cavalry on the extreme right. Marius had also very sensibly formed up his lines facing west, therefore the Cimbri had to fight with the sun in their eyes.[18]

The Romans got into position first, the sun reflected off their armour. The Cimbri thought the sky was on fire and became very unnerved. Sensing their sudden anxiety, the Romans attacked. Marius led his wing against the Cimbri right. He marched into a huge dust cloud created by a quarter of a million men on the move across dry fields. When he emerged he did not find the enemy, the battle was taking place somewhere else. The Cimbri had launched themselves in a huge wedge towards Catulus's centre, their cavalry to the front. Unfortunately for the Cimbri their horsemen were taken completely by surprise by the superior Roman cavalry under the command of Sulla. The Cimbri horse were forced back into the main body of their infantry, causing chaos. Seeing an opportunity Catulus threw his men forward and they were soon in hand-to-hand combat. The other wings of the Roman army soon moved in on the German flanks hemming them in. The Roman forces were smaller but more highly trained and disciplined. Furthermore, Roman legionaries excelled at close-quarters combat, and so tightly packed they were in their element. The summer heat also worked against the barbarians who were not accustomed to fighting in these temperatures (the Romans living around the Mediterranean were). The battle became a rout, stopped by the wagons drawn up (as was customary among Germanic and Celtic peoples) at the rear of the battle field. At this point the rout became a massacre that stopped only when the Cimbri began to surrender en masse. Boiorix and his noblemen made a last stand in which they were all killed. The Romans had won a complete and stunning victory.[19]

Aftermath

The victory of Vercellae, following close on the heels of Marius' destruction of the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae the previous year, put an end to the Germanic threat to Rome's northern frontiers. The Cimbri were virtually wiped out, with Marius claiming to have killed 100,000 warriors and capturing and enslaving many thousands, including large numbers of women and children. Children of the surviving captives may have been among the rebelling gladiators in the Third Servile War.[20]

The news of the decisive victory at Vercellae was brought to Rome by Marius's brother-in-law, Gaius Julius Caesar (father of the famous Julius Caesar), who in the next year would become father to his only son.[1]

Marius and Catulus were soon at odds with each other about who deserved the most credit.[21] Marius tried to claim all the credit for the victory (which was his right as overall commander), but Catulus took citizens of nearby Parma to the battlefield and showed them the bodies of the Cimbri many of whom still had the pilums that killed them embedded in their corpses, and the vast majority of these pilums (pila) carried the markings of Catulus' legionaries.[22]

Eventually, Marius and Catulus held a joint Triumph with Marius getting the most praise as overall commander.[22]

Politically, this battle had great implications for Rome as well. The main reason (the Germanic threat) for Marius's string of continuous consulships (104 BC-101BC) was gone. Although Marius, riding a wave of popularity after the Vercellae victory, was elected consul (for 100 BC) again, his political opponents exploited this. The end of the war also saw the beginning of a growing rivalry between Marius and Sulla, which would eventually lead to the first of Rome's great civil wars. As a result of his role in the Vercellae victory Sulla's prestige had risen considerably. Marius's career was at its peak while Sulla's was still on the rise.

Immediately after the battle Marius granted Roman citizenship to his Italian allied forces without consulting or asking permission from the Senate first. When some senators questioned this action, he would claim that in the heat of battle he could not distinguish the voice of a Roman from that of an ally. From that day, all Italian legions would be regarded as Roman legions.[1]

This action by Marius was the first time a victorious general had openly defied the Senate but it would not be the last. In 88 BC, Sulla, in defiance of both the Senate and tradition, would lead his troops into the city of Rome itself. And Julius Caesar, when ordered by the Senate to lay down his command and return to Rome to face misconduct charges, would instead lead one of his legions across the Rubicon in 49 BC. This would mark the start of the civil war between himself and senatorial forces under Pompey which would lead to the end of the Roman Republic.

See also

In literature

- Colleen McCullough describes the battle in some detail in her novel The First Man in Rome, the first book in her Masters of Rome series. Marius is one of the main characters and the novel focusses on his rise to power.

References

- ^ a b c Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 65.

- ^ "A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information". The Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5–6 (11 ed.). Pennsylvania State University: The University Press. 1911.

- ^ Dawson, Edward. "Cimbri & Teutones". The History Files. Kessler Associates. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 41.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 42.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 42-43.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 45-51.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p.58.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 57-58.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 60-61.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 65; Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain, pp 14-15.

- ^ Sampson 2010, p. 168.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 64.

- ^ Sampson 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, pp 64-65; Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain, p. 13.

- ^ for instance: Zennari, Jacopo (1958). La battaglia dei Vercelli o dei Campi Raudii (101 a. C.) (in Italian). Cremona: Athenaeum cremonense.

- ^ Descriptive material in the Ethnological Museum of the Castle of Grinzane Cavour.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 64-6; Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain, p. 13.

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 65; Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain, pp 13-14; Plutarch, Life of Marius, section 27.

- ^ Barry Strauss, The Spartacus War, p. 21

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 66; Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 39.

- ^ a b Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 39.

- Sources

- Sampson, Gareth (2010). The Crisis of Rome: The Jugurthine and Northern Wars and the Rise of Marius. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-972-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mommsen, Theodor, History of Rome, Book IV "The Revolution", pp 71–72.

- Florus, Epitome rerum Romanarum, III, IV, partim

- Todd, Malcolm, The Barbarians: Goths, Franks and Vandals, pp 121–122.