Bezenšek Shorthand

| Bezenšek Shorthand | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

| Creator | Anton Bezenšek |

Time period | 1923–today |

| Languages | Bulgarian |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Gabelsberger shorthand

|

Bezenšek Shorthand is a shorthand system, used for rapidly recording Bulgarian speech. The system was invented by the Slovene linguist Anton Bezenšek c. 1879. It is based on the Gabelsberger shorthand (used for German), so it is often referred to as the Gabelsberger–Bezenšek Shorthand. (More precisely, Bezenšek Shorthand is based on a system by Heger — one of Gabelsberger's students, who adapted the system for the Czech language.)

Overview[edit]

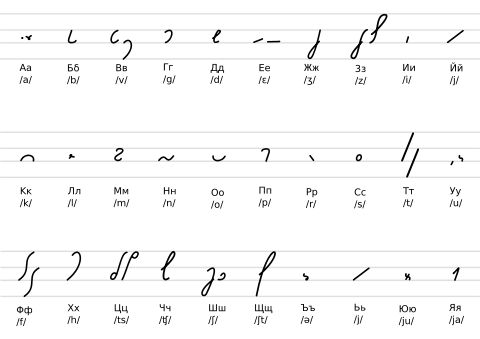

Bezenšek Shorthand has features of a phonetic system, though Bulgarian writing almost identically represents the sounds in speech. It is acceptable to replace certain closely related sounds with each other, for the sake of simplicity and speed, e. g. s for z, e for ya, svo for stvo, etc. The system is not an alphabetic one, but closer to a syllabic one, though many syllables are normally skipped. Vowels are usually not recorded as separate strokes, but are marked via modifying the preceding or following consonant, similarly to an abugida.

The shorthand's form is based on borrowings from natural longhand, as opposed to geometric or elliptical systems, such as Gregg and Pitman. The strokes are distinguishable by size, proportion, position (three of them: above, below, or on the base line), and shading (variation of thickness of strokes). Shading, normally used for marking an /a/ vowel, is nowadays difficult to achieve with a ballpoint pen, but at the time of invention was convenient for marking, using the then-ubiquitous pencils. Nevertheless, ambiguity is close to none, even when thickness is not marked, because words are easily recognizable from the context.

Several letters can be written in two different ways:

- The pairs of strokes for Ее /ɛ/, Фф /f/, and Тт /t/ can be used interchangeably.

- The first stroke for Зз /z/, Цц /ts/, and Уу /u/ is used only in the beginning of a word.

- The second stroke for Вв /v/ and Шш /ʃ/ can be used only in the end of a word.

- Both stroke for Аа /a/ can be used for an isolated (possibly an abbreviation) /a/, but only the second sign is used as part of a word. Note, that /a/ is normally marked by shading of the preceding consonant.

- One of connecting lines of Аа /a/ or Лл /l/ may be omitted when part of a word.

Йй and Ьь represent the same sound /j/, so they share the same stroke.

Сиглообразуване: (в)се, повече, все повече, все повече и повече.

The system has a set of compulsory abbreviations, called sigli (Bulgarian: сигли; singular: сигла, sigla), and recommends rules for forming free abbreviations. Punctuation consists only of a period, written as a small horizontal segment on the base line, because the dot, comma, question mark, exclamation mark, and others, have special meaning and could be confused with words. Colons and double quotes are acceptable, especially for beginners. Digits are similar to the Arabic numerals, except for 5 and 7, which can be written without a horizontal bar; also, special notation is normally applied for hundreds, thousands, and millions. Abbreviation of whole phrases into a single connected sequence of strokes is allowed and encouraged.

History[edit]

In 1878 Bulgaria was liberated from a five-century Ottoman rule, and a government was formed. Initially, discussions in Parliament were recorded by conventional scribes, and arguments about the accuracy of records were not uncommon. Slovenian linguist Bezenšek, who had already had experience with adapting shorthand to other Slavic languages, was invited. He accepted and came up with a solution, although he was not a proficient speaker of Bulgarian at first.

As the system developed, it required corrections, which Bezenšek coped with well. In the following decades, however, improvements were more and more difficult to make, hindered by new teachers who had already published books, that were then expensive to re-print. Most of those book authors had ideas about improvements of their own, but only a few could manage to gain control of the "official" version. The system became quite conservative, a lot of suggestions were rejected, including some proposed by Bezenšek himself. Some suggestions were rejected without even being taken into consideration. The existing system was announced unique, official, compulsory, and "best in the world". Competition was banned — a participant in a shorthand competition was once disqualified for using an alternative system.

Shortly after the Communist party took power in 1944, all existing shorthand organizations were dismissed, and the National Shorthand Institute was established. It kept on resisting reforms until the 1960s, when a contest was held. At first no propositions were accepted, which caused a scandal, so after re-examination four of them were approved. Unfortunately it was reported to the Minister of Education, that the new speed results were worse than before, so the old system once again survived. Another fruitless contest was held in the 1980s.

As a result, the 1923 version of Bezenšek-Gabelsberger remained official until the National Shorthand Institute was shut down in Democratic Bulgaria. Presently, newer systems are taught at universities, but are not regulated and none of them is a monopoly.

Criticism[edit]

- Shading is difficult to express with a ballpoint pen. This also reduces readability for learners.

- Positioning might lead to ambiguity, as the same sign can often mean different things when put at different positions.

- Steep learning curve — the great number of consonantal blends and abbreviations ("sigli") require quite some time for a beginner to start using the system effectively.

- Suitability for Bulgarian is disputed, as the system was created for the unrelated German language, and Bezenšek had become fluent in Bulgarian just shortly before he invented it. To a certain extent, this resulted in some waste of elegant natural strokes for infrequent sounds, and a redundancy of complex slow strokes for common sounds. Neither does the system fit well with the increasing number of loanwords from English.

Sources[edit]

- "Shorthand in Bulgaria" (in Bulgarian). Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved 27 August 2006.

- Georgi Trapchev; Lyubomir Velchev; Georgi Botev (1971). Stenografia (in Bulgarian). "Narodna Prosveta" state publishing company.