Brown-headed cowbird

| Brown-headed Cowbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult male | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | M. ater

|

| Binomial name | |

| Molothrus ater | |

| |

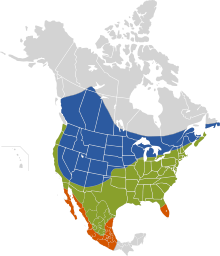

| blue: breeding; green: year-round; ochre: nonbreeding | |

The Brown-headed Cowbird (Molothrus ater) is a small brood parasitic icterid of temperate to subtropical North America. They are permanent residents in the southern parts of their range; northern birds migrate to the southern United States and Mexico in winter, returning to their summer habitat about March/April.[1]

They resemble New World orioles in general shape but have a finch-like head and beak. Adults have a short finch-like bill and dark eyes. The adult male is mainly iridescent black with a brown head. The adult female is grey with a pale throat and fine streaking on the underparts.

Ecology

Habitat

They occur in open or semi-open country and often travel in flocks, sometimes mixed with Red-winged Blackbirds (particularly in spring) and Bobolinks (particularly in fall), as well as Common Grackle or European Starlings.[1] These birds forage on the ground, often following grazing animals such as horses and cows to catch insects stirred up by the larger animals. They mainly eat seeds and insects.

Before European settlement, the Brown-headed Cowbird followed bison herds across the prairies. Their parasitic nesting behaviour complemented this nomadic lifestyle. Their numbers expanded with the clearing of forested areas and the introduction of new grazing animals by settlers across North America. Brown-headed Cowbirds are now commonly seen at suburban birdfeeders.

Reproduction

This bird is a brood parasite: it lays its eggs in the nests of other small passerines (perching birds), particularly those that build cup-like nests. The Brown-headed Cowbird eggs have been documented in nests of at least 220 host species, including hummingbirds and raptors.[2] (Ortega 1998) The young cowbird is fed by the host parents at the expense of their own young. Brown-headed Cowbird females can lay 36 eggs in a season. More than 140 different species of birds are known to have raised young cowbirds.[3]

Unlike the Common Cuckoo, it has no gentes whose eggs imitate those of a particular host.

Host-parasite interactions

Egg rejection

Host parents may sometimes easily notice the cowbird egg, to which different host species react in different ways. Rejection manifests in three forms: nest desertion (e.g., Blue-gray Gnatcatcher), burying of the egg under nest material (e.g., Yellow Warbler)[4], and physical ejection of the egg from the nest (e.g., Brown Thrasher).[5] Brown-headed cowbird nestlings are sometimes expelled from the nest.

Unsuitable diet

The House Finch feeds its young a vegetarian diet, which is unsuitable for young Brown-headed Cowbirds. Although the Brown-headed Cowbird eggs laid in a House Finch nest will hatch, almost none survive to fledge.[6]

Parasite response

It seems that Brown-headed Cowbirds periodically check on their eggs and young after they have deposited them. Removal of the parasitic egg may trigger a retaliatory reaction termed "mafia behavior". According to a study by the Florida Museum of Natural History published in 1983, the cowbird returned to ransack the nests of a range of host species 56% of the time when their egg was removed. In addition, the cowbird also destroyed nests in a type of "farming behavior" to force the hosts to build new ones. The cowbirds then laid their eggs in the new nests 85% of the time.[7]

Footnotes

- ^ a b Henninger (1906)

- ^ Friedman and Kiff, Herbert and Lloyd F. (1985-05-16). "The parasitic cowbirds and their hosts". Proceedings of the Western Foundation of Vertebrate Zoology. 2 (4): 225–304.

- ^ Jaramillo, Alvaro (1999). New World Blackbirds: The Iceterids. London: Christopher Helm. p. 382.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sealy, SPENCER G. (1995). "Burial of cowbird eggs by parasitized yellow warblers: an empirical and experimental study". Animal Behaviour. 49 (4). The Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour: 877. doi:10.1006/anbe.1995.0120. Retrieved 2008-07-25.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ortega (1998)

- ^ Kozlovic, Knapton, and Barlow, Daniel R., Richard W., and Jon C. (1996). "Unsuitability of the House Finch as a Host of the Brown-Headed Cowbird" (PDF). The Condor. 96 (2). Retrieved 2008-07-25.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoover & Robinson (2007)

References

- Template:IUCN2006 Database entry includes justification for why this species is of least concern

- Henninger, W.F. (1906): A preliminary list of the birds of Seneca County, Ohio. Wilson Bull. 18(2): 47-60. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

- Hoover, Jeffrey P. &. Robinson, Scott K. (2007): Retaliatory mafia behavior by a parasitic cowbird favors host acceptance of parasitic eggs. PNAS 104(11): 4479-4483. doi:10.1073/pnas.0609710104 PDF fulltext

- Ortega, C.P. (1998) Cowbirds and Other Brood Parasites. University of Arizona Press, Tucson.