Buddhist influences on Christianity

It is agreed by most scholars that Buddhism was known in the pre-Christian Greek world through the campaigns of Alexander the Great (see Greco-Buddhism and Greco-Buddhist monasticism), and several prominent early Christian fathers (Clement of Alexandria and St. Jerome) were certainly aware of the Buddha, even mentioning him in their works.[1][2]

Some historians such as Jerry H. Bentley and Elaine Pagels suggest that there is a real possibility that Buddhism influenced the early development of Christianity".[3]

There have also been suggestions of an indirect path in which Indian Buddhism may have influenced Gnosticism and then Christianity.[4] Some scholars hold that the suggested similarities are coincidental since parallel traditions may emerge in different cultures.[5]

Despite suggestions of surface level analogies, Buddhism and Christianity have inherent and fundamental differences at the deepest levels, such as monotheism's place at the core of Christianity and Buddhism's orientation towards non-theism.[6][7]

In the East, the syncretism between Nestorian Christianity and Buddhism was deep and widespread along the Silk Road, and was especially pronounced in the medieval Church of the East in China.[8] There are also historical documents showing the syncretic nature of Christianity and Buddhism in Asia such as the Jesus Sutras and Nestorian Stele.

Early Christianity

Suggestions of influence

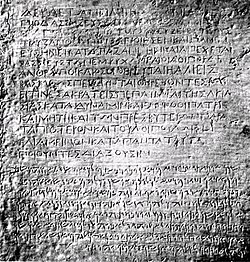

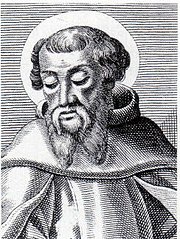

Will Durant, noting that the Emperor Ashoka sent missionaries, not only to elsewhere in India and to Sri Lanka, but to Syria, Egypt and Greece, first speculated in the 1930s that they may have helped prepare the ground for Christian teaching.[9] Buddhism was prominent in the eastern Greek world (Greco-Buddhism) and became the official religion of the eastern Greek successor kingdoms to Alexander the Great's empire (Greco-Bactrian Kingdom (250 BC-125 BC) and Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BC - 10 CE)). Several prominent Greek Buddhist missionaries are known (Mahadharmaraksita and Dharmaraksita) and the Indo-Greek king Menander I converted to Buddhism, and is regarded as one of the great patrons of Buddhism. (See Milinda Panha.) Some modern historians have suggested that the pre-Christian monastic order in Egypt of the Therapeutae is possibly a deformation of the Pāli word "Theravāda,"[10] a form of Buddhism, and the movement may have "almost entirely drawn (its) inspiration from the teaching and practices of Buddhist asceticism".[11] They may even have been descendants of Asoka's emissaries to the West.[12] It is true that Buddhist gravestones from the Ptolemaic period have also been found in Alexandria in Egypt, decorated with depictions of the Dharma wheel, showing the Buddhists were living in Hellenistic Egypt at the time Christianity began.[13] The presence of Buddhists in Alexandria has led one author to note: "It was later in this very place that some of the most active centers of Christianity were established".[14] The early church father Clement of Alexandria (died 215 AD) was also aware of Buddha, writing in his Stromata (Bk I, Ch XV): "The Indian gymnosophists are also in the number, and the other barbarian philosophers. And of these there are two classes, some of them called Sarmanæ and others Brahmins. And those of the Sarmanæ who are called "Hylobii" neither inhabit cities, nor have roofs over them, but are clothed in the bark of trees, feed on nuts, and drink water in their hands. Like those called Encratites in the present day, they know not marriage nor begetting of children. Some, too, of the Indians obey the precepts of Buddha (Βούττα) whom, on account of his extraordinary sanctity, they have raised to divine honours."[15]

Nicolaus of Damascus, and other ancient writers, relate that in AD 13, at the time of Augustus (died AD 14), he met in Antioch (near present day Antakya in Turkey just over 300 miles from Jerusalem) an embassy with a letter written in Greek from the Southern India Pandya Empire was delivered while Caesar was in the Island of Samos. This embassy was accompanied by a sage who later, naked, anointed and contented, burnt himself to death at Athens.[16] The details of his tomb inscription specified he was a Shramana, "his name was Zarmanochegas", he was an Indian native of Bargosa, and "immortalized himself according to the custom of his country." Cassius Dio [17] and Plutarch [18] cite the same story. Historian Jerry H. Bentley (1993) notes "the possibility that Buddhism influenced the early development of Christianity" and that scholars "have drawn attention to many parallels concerning the births, lives, doctrines, and deaths of the Buddha and Jesus".[19]

The suggestion that an adult Jesus traveled to India and was influenced by Buddhism before starting his ministry in Galilee was first made by Nicolas Notovitch in 1894 in the book The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ which was widely disseminated and became the basis of other theories.[20][21] Notovitch's theory was controversial from the beginning and was widely criticized.[22][23] Once his story had been re-examined by historians, Notovitch confessed to having fabricated the evidence.[23][24]

Rejections of influence

Many scholars believe there is no historical evidence of any influence by Buddhism on Christianity, Paula Fredriksen stating that no serious scholarly work has placed the origins of Christianity outside the backdrop of 1st century Palestinian Judaism.[26] Leslie Houlden states that although modern parallels between the teachings of Jesus and Buddha have been drawn, these comparisons emerged after missionary contacts in the 19th century and there is no historically reliable evidence of contacts between Buddhism and Jesus.[27]

Other scholars such as Eddy and Boyd state that there is no evidence of a historical influence by outside sources on the authors of the New Testament, and most scholars agree that any such historical influence on Christianity is entirely implausible given that first century monotheistic Galilean Jews would not have been open to what they would have seen as pagan stories.[28][29] The Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism states that theories of influences of Buddhism on early Christianity are without historical foundation.[30]

Modern scholarship has roundly rejected any historical basis for the travels of Jesus to India or Tibet or influences between the teachings of Christianity and Buddhism, and has seen the attempts at parallel symbolism as cases of parallelomania which exaggerate the importance of trifling resemblances.[27][29][31][32]

There are inherent and fundamental differences between Buddhism and Christianity, one significant element being that while Christianity is at its core monotheistic and relies on a God as a Creator, Buddhism is generally non-theistic and rejects the notion of a Creator God which provides divine values for the world.[6][7]

The central iconic imagery of the two traditions underscore the difference in their belief structure, when the peaceful death of Gautama Buddha at an old age is contrasted with the harsh image of the crucifixion of Jesus as a willing sacrifice for the atonement for the sins of humanity.[33] Buddhists scholars such as Masao Abe see the centrality of crucifixion in Christianity as an irreconcilable gap between the two belief systems.[34][35]

Post Apostolic Age

Church Fathers

Clement of Alexandria referred to Buddhists and wrote:[2]

"Among the Indians are those philosophers also who follow the precepts of Boutta (Βούττα), whom they honour as a god on account of his extraordinary sanctity."

— Clement of Alexandria, Stromata (Miscellanies), Book I, Chapter XV

Early 3rd–4th century Christian writers such as Hippolytus and Epiphanius write of one Scythianus who visited India around 50 CE, whence he brought the "doctrine of the Two Principles". Scythianus' pupil Terebinthus supposedly presented himself as a "Buddha" ("he called himself Buddas" Cyril of Jerusalem) and became well known in Judaea and was said to have conversed with the apostles and to have brought books back from his trade with India. The same author says his books and knowledge were taken over by Mani, and became the foundation of the Manichean doctrine.[a]

"Terebinthus, his disciple in this wicked error, inherited his money and books and heresy, and came to Palestine, and becoming known and condemned in Judaea he resolved to pass into Persia: but lest he should be recognised there also by his name he changed it and called himself Buddas."

— Cyril of Jerusalem, Sixth Catechetical Lecture Chapter 22-24[36]

Saint Jerome (4th century CE) mentions that the Buddhist belief of Buddha's birth from a virgin as their "opinion [...] authoritatively handed down that Budda, the founder of their religion, had his birth through the side of a virgin,"[37] (the Buddha was, according to Buddhist tradition, born from the hip of his mother).[38] It has been suggested that this virgin birth legend of Buddhism influenced Christianity.[1]

Gnosticism

Gnosticism refers to a number of small Christian sects which existed in the 2nd-5th centuries, and were rejected by mainstream Christians as heretics. There were some contacts between Gnostics and Indians, e.g. Syrian gnostic theologian Bar Daisan describes in the 3rd century his exchanges with missions of holy men from India (Greek: Σαρμαναίοι, Sramanas), passing through Syria on their way to Elagabalus or another Severan dynasty Roman Emperor. His accounts are quoted by Porphyry (De abstin., iv, 17 [3]) and Stobaeus (Eccles., iii, 56, 141).

This has given rise to suggestions by Zacharias P. Thundy that Buddhist tradition may have influenced Gnosticism and hence Christianity.[4] Thundy has also considered possible influences through the Jewish sect Therapeutae, which he suggests could have been Buddhists in the first century.[4]

However, Gnosticism was harshly rejected by Christians and c. 180 Irenaeus wrote against them at length in his On the Detection and Overthrow of the So-Called Gnosis, generally called Against Heresies.[39] By the third century Indians were also considered heretics by the Christians who condemned their practices.[4]

Elaine Pagels has encouraged research into the impact of Buddhism on Gnosticism, but she holds that although intriguing, the evidence of any influence is inconclusive.[5][40] She further concludes that these parallels might be coincidental since parallel traditions may emerge in different cultures.[5][40]

See also

References

- ^ a b McEvilley, p391

- ^ Clement of Alexandria Stromata. BkI, Ch XV http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.vi.iv.i.xv.html (Accessed 19 Dec 2012)

- ^ Bentley, Jerry H. (1992). Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. Oxford University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-19-507640-0.

- ^ a b c d Buddha and Christ by Zacharias P. Thundy (Jan 1, 1993) ISBN 9004097414 pages 206-208 Cite error: The named reference "Thundy" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Philosophers Explore The Matrix by Christopher Grau (Sep 1, 2005) ISBN 0195181069 Oxford Univ Press page 259

- ^ a b The Boundaries of Knowledge in Buddhism, Christianity, and Science by Paul D Numrich (Dec 31, 2008) ISBN 3525569874 page 10

- ^ a b Communicating Christ in the Buddhist World by Paul De Neui and David Lim (Jan 1, 2006) ISBN 0878085106 page 34

- ^ In the 13th century, international travelers, such as Giovanni de Piano Carpini and William of Ruysbroeck, sent back reports of Buddhism to the West and noted the similarities to Nestorian Christian beliefs .Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism, 2004, page 160

- ^ 1. Will Durant, The Story of Civilization: Our Oriental Heritage, Part One (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1935), vol. 1, p. 449.

- ^ According to the linguist Zacharias P. Thundy

- ^ Living Zen by Robert Linssen (Grove Press New York, 1958) ISBN 0-8021-3136-0

- ^ "The Original Jesus" (Element Books, Shaftesbury, 1995), Elmar R Gruber, Holger Kersten

- ^ The Greeks in Bactria and India, W.W. Tarn, South Asia Books, ISBN 81-215-0220-9'

- ^ [Living Zen by Robert Linssen (Grove Press New York, 1958) ISBN 0-8021-3136-0

- ^ Clement of Alexandria Stromata. BkI, Ch XV http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.vi.iv.i.xv.html (Accessed 19 Dec 2012)

- ^ Strabo, Geography Bk XV, Ch1, 73

- ^ Hist 54.9,

- ^ 69,1

- ^ Bentley, Jerry H. (1993). Old World Encounters. Cross-cultural contacts and exchanges in pre-modern times. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507639-7.

- ^ The Unknown Life Of Jesus Christ: By The Discoverer Of The Manuscript by Nicolas Notovitch (Oct 15, 2007) ISBN 1434812839

- ^ Forged: Writing in the Name of God--Why the Bible's Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are by Bart D. Ehrman (Mar 6, 2012) ISBN 0062012622 page 252 "one of the most widely disseminated modern forgeries is called The Unknown Life of Jesus Christ"

- ^ Simon J. Joseph, "Jesus in India?" Journal of the American Academy of Religion Volume 80, Issue 1 pp. 161-199 "Max Müller suggested that either the Hemis monks had deceived Notovitch or that Notovitch himself was the author of these passages"

- ^ a b New Testament Apocrypha, Vol. 1: Gospels and Related Writings by Wilhelm Schneemelcher and R. Mcl. Wilson (Dec 1, 1990) ISBN 066422721X page 84 "a particular book by Nicolas Notovich (Di Lucke im Leben Jesus 1894) ... shortly after the publication of the book, the reports of travel experiences were already unmasked as lies. The fantasies about Jesus in India were also soon recognized as invention... down to today, nobody has had a glimpse of the manuscripts with the alleged narratives about Jesus"

- ^ Indology, Indomania, and Orientalism by Douglas T. McGetchin (Jan 1, 2010) Fairleigh Dickinson University Press ISBN 083864208X page 133 "Faced with this cross-examination, Notovich confessed to fabricating his evidence."

- ^ New Testament Christology by Frank J. Matera 1999 ISBN 0-664-25694-5 page 67

- ^ Fredriksen, Paula. From Jesus to Christ. Yale University Press, 2000, p. xxvi.

- ^ a b Jesus: The Complete Guide 2006 by Leslie Houlden ISBN 082648011X page 140

- ^ The Jesus legend: a case for the historical reliability of the synoptic gospels by Paul R. Eddy, Gregory A. Boyd 2007 ISBN 0-8010-3114-1 page 53-54

- ^ a b Gerald O'Collins, "The Hidden Story of Jesus" New Blackfriars Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008

- ^ Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One) by Robert E. Buswell (Feb 2004) ISBN 0028657195 Macmillan pages 159

- ^ Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 page 17

- ^ The Historical Jesus in Recent Research edited by James D. G. Dunn and Scot McKnight 2006 ISBN 1-57506-100-7 page 303

- ^ Jesus: The Complete Guide by J. L. Houlden (Feb 8, 2006) ISBN 082648011X pages 140-144

- ^ Buddhism and Interfaith Dialogue by Masao Abe and Steven Heine (Jun 1, 1995) ISBN pages 99-100

- ^ Mysticism, Christian and Buddhist by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki ((Aug 4, 2002)) ISBN 1605061328 page 113

- ^ a b Catholic Encyclopedia (Public Domain, quoted in [1])

- ^ Jerome-Against-Jovinianus, 815, Online Viewing: http://www.patriarchywebsite.com/bib-patriarchy/Jerome-Against-Jovinianus.txt

- ^ Andre Grabar "Christian iconography, a study of its origins", p129

- ^ The Ancient World: Dictionary of World Biography (Vol 1) by Frank N. Magill (Mar 1, 1999) ISBN 1579580408 page 597

- ^ a b Pagels, Elaine (1989) [1979]. The Gnostic Gospels. New York: Random House.

Notes

- ^ Cyril of Jerusalem, Sixth Catechetical Lecture Chapter 22-24:

"22. There was in Egypt one Scythianus, a Saracen by birth, having nothing in common either with Judaism or with Christianity. This man, who dwelt at Alexandria and imitated the life of Aristotle, composed four books, one called a Gospel which had not the acts of Christ, but the mere name only, and one other called the book of Chapters, and a third of Mysteries, and a fourth, which they circulate now, the Treasure. This man had a disciple, Terebinthus by name. But when Scythianus purposed to come into Judaea, and make havoc of the land, the Lord smote him with a deadly disease, and stayed the pestilence.

23. But Terebinthus, his disciple in this wicked error, inherited his money and books and heresy, and came to Palestine, and becoming known and condemned in Judaea he resolved to pass into Persia: but lest he should be recognised there also by his name he changed it and called himself Buddas. However, he found adversaries there also in the priests of Mithras: and being confuted in the discussion of many arguments and controversies, and at last hard pressed, he took refuge with a certain widow. Then having gone up on the housetop, and summoned the daemons of the air, whom the Manichees to this day invoke over their abominable ceremony of the fig, he was smitten of God, and cast down from the housetop, and expired: and so the second beast was cut off.

24. The books, however, which were the records of his impiety, remained; and both these and his money the widow inherited. And having neither kinsman nor any other friend, she determined to buy with the money a boy named Cubricus: him she adopted and educated as a son in the learning of the Persians, and thus sharpened an evil weapon against mankind. So Cubricus, the vile slave, grew up in the midst of philosophers, and on the death of the widow inherited both the books and the money. Then, lest the name of slavery might be a reproach, instead of Cubricus he called himself Manes, which in the language of the Persians signifies discourse. For as he thought himself something of a disputant, he surnamed himself Manes, as it were an excellent master of discourse. But though he contrived for himself an honourable title according to the language of the Persians, yet the providence of God caused him to become a self-accuser even against his will, that through thinking to honour himself in Persia, he might proclaim himself among the Greeks by name a maniac." [36]

Sources

- Johnston, William, S.J., Christian Zen, Harper & Row, 1971. ISBN 0-8232-1801-5

- Leaney, A.R.C., ed., A Guide to the Scrolls, Nottinham Studies on the Qumran Discoveries, SCM Book Club, Naperville, Ill., 1958.

- Lefebure, Leo D., The Buddha and the Christ, Explorations in Buddhist and Christian Dialogue (Faith Meets Faith Series), Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York, 1993.

- Maguire, Jack (2001). Essential Buddhism. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-671-04188-6.

- India in Primitive Christianity, Kegan House Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1909.

- Lopez, Donald S. & Rockefeller, Steven C., eds., The Christ and the Bodhisattva, State University of New York, 1987. Phan, Peter, ed., Christianity and the Wider Ecumenism, Paragon House, New York, 1990.

- Siegmund, Georg, Buddhism and Christianity, A Preface to Dialogue, Sister Mary Frances McCarthy, trans., University of Alabama Press, 1968.

- Yu, Chai-shin, Early Buddhism and Christianity, A comparative Study of the Founders' Authority, the Community, and the Discipline, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1981.