Burleigh Grimes

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2011) |

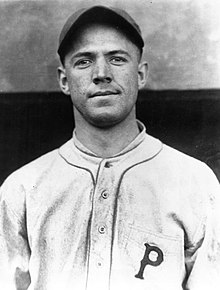

| Burleigh Grimes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Pitcher / Manager | |

| Born: August 18, 1893 Emerald, Wisconsin | |

| Died: December 6, 1985 (aged 92) Clear Lake, Wisconsin | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 10, 1916, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 20, 1934, for the Pittsburgh Pirates | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Win–loss record | 270–212 |

| Earned run average | 3.53 |

| Strikeouts | 1,512 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Managerial record at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1964 |

| Election method | Veteran's Committee |

Burleigh Arland Grimes (August 18, 1893 – December 6, 1985) was an American professional baseball player, and the last pitcher officially permitted to throw the spitball. Grimes made the most of this advantage and he won 270 games and pitched in four World Series over the course of his 19-year career. He was elected to the Wisconsin Athletic Hall of Fame in 1954, and to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964.

Early life

Grimes was born in Emerald, Wisconsin. He was the first child of Nick Grimes, a farmer and former day laborer, and the former Ruth Tuttle, the daughter of a former Wisconsin legislator. Having previously played baseball for several local teams, Nick Grimes managed the Clear Lake Yellow Jackets and taught his son how to play the game early in life.[1] Burleigh Grimes also participated in boxing as a child.[2]

He made his professional debut in 1912 for the Eau Claire Commissioners of the Minnesota–Wisconsin League.[3] He played in Ottumwa, Iowa, in 1913 for the Ottumwa Packers in the Central Association.

MLB career

Grimes played for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1916 and 1917. Before the 1918 season, he was sent to the Brooklyn Dodgers in a multiplayer trade.[4] When the spitball was banned in 1920, he was named as one of the 17 established pitchers who were allowed to continue to throw the pitch. According to Baseball Digest, the Phillies were able to hit him because they knew when he was throwing the spitter. The Dodgers were mystified about this; first they thought the relative newcomer of a catcher, Hank DeBerry, was unwittingly giving away his signals to the pitcher, so they substituted veteran Zack Taylor, to no avail. They suggested that a spy with binoculars was concealed in the scoreboard in old Baker Bowl in Philadelphia, reading the signals from a distance, but the Phils hit Grimes just as well in Ebbets Field in Brooklyn. A batboy solved the mystery by pointing out that Burleigh's cap was too tight. It sounded silly, but he was right. The tighter cap would wiggle when Grimes flexed his facial muscles to prepare the spitter. He got a cap a half-size larger and the Phillies were on their own after that.[citation needed]

He then pitched for the New York Giants (1927), the Pirates again (1928–1929), the Boston Braves (1930) and the St. Louis Cardinals (1930-1931). He was traded to the Chicago Cubs before the 1932 season in exchange for Hack Wilson and Bud Teachout.[5] He returned to the Cardinals in 1933 and 1934, then moved to the Pirates (1934) and the New York Yankees (1934). Grimes was nicknamed "Ol' Stubblebeard", related to his habit of not shaving on days in which he was going to pitch.[6]

At the time of his retirement, he was the last of the 17 spitballers left in the league. He had acquired a lasting field reputation for his temperament. He is listed in the Baseball Hall of Shame series for having thrown a ball at the batter in the on-deck circle.[7] His friends and supporters note that he was consistently a kind man when off the diamond. Others claim he showed a greedy attitude to many people who 'got on his bad side.' He would speak mainly only to his best friend Ivy Olson in the dugout, and would pitch only to a man named Mathias Schroeder before games. Schroeder's identity was not well known among many Dodger players, as many say he was just 'a nice guy from the neighborhood.'

Post-playing career

Grimes moved to the minor leagues in 1935 as a player-manager for the Bloomington Bloomers of the Illinois–Indiana–Iowa League. He started 21 games for the team, recording a 2.34 ERA and a 10-5 record.[8] He did not pitch again after that season, moving on to manage the Louisville Colonels of the American Association.[8]

Grimes was the manager of the Dodgers in 1937-38. He followed Casey Stengel's term as Dodgers manager.[9] He compiled a two-year record of 131-171 (.434), with his teams finishing sixth and seventh respectively in the National League. Babe Ruth was one of Grimes's coaches. Leo Durocher was the team's shortstop in 1937 and a coach in 1938.[10] When Grimes was fired by general manager Larry MacPhail after the 1938 season, Durocher was hired to replace him. MacPhail said that the team's morale had not been right for a long period of time.[11]

Grimes remained in baseball for many years as a minor league manager and a scout. He managed the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League from 1942 to 1944, and again in 1952 and 1953, winning the pennant in 1943. As a scout with the Baltimore Orioles, Grimes discovered Jim Palmer and Dave McNally.[10] Grimes also assisted in managing the Independence Yankees in Independence, Kansas in 1948 and 1949, where Mickey Mantle started his professional career in 1949.[12]

Later life

Grimes was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1964. In 1981, Lawrence Ritter and Donald Honig included Grimes in their book The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.

Grimes died of cancer in 1985 in Clear Lake, Wisconsin. His wife Lillian survived him.[9]

See also

- List of Major League Baseball career wins leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual strikeout leaders

- List of Major League Baseball annual wins leaders

- List of members of the Baseball Hall of Fame

- List of Major League Baseball career hit batsmen leaders

Notes

- ^ Niese, p. 10.

- ^ Niese, p. 12.

- ^ Christofferson, Jason. Diamonds in Clear Water: Professional Baseball in Eau Claire, 1886–1912. Self-published. 2013. p.143-155.

- ^ "Robins give Pirates two players for three in big trade; Mamaux obtained by Robins in deal". The New York Times. January 10, 1918. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ Snyder, John (2010). Cardinals Journal: Year by Year and Day by Day with the St. Louis Cardinals Since 1882. Clerisy Press. ISBN 157860480X. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- ^ "Grimes, Burleigh". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ Bruce Nash, The Baseball Hall of Shame 2

- ^ a b "Burleigh Grimes Minor League Statistics & History". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ a b Yannis, Alex (December 10, 1985). "Burleigh Grimes, ex-pitcher and Hall of Fame member". The New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- ^ a b "Grimes back at "home"". Milwaukee Sentinel. February 4, 1972. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ ""Lippy" peps up Dodgers". Pittsburgh Press. October 13, 1938. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

- ^ Niese, Joe (2013). Burleigh Grimes: Baseball's Last Legal Spitballer. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-0179-3.

References

- Niese, Joe (2013). [Burleigh Grimes: Baseball's Last Legal Spitballer http://books.google.com/books?id=6QKTmVNGltIC]. McFarland. ISBN 0786473282.

External links

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Burleigh Grimes at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- cmgworldwide.com Official website[dead link]

- 1893 births

- 1985 deaths

- Baltimore Orioles scouts

- Baseball players from Wisconsin

- Birmingham Barons players

- Bloomington Bloomers players

- Boston Braves players

- Brooklyn Dodgers managers

- Brooklyn Robins players

- Chattanooga Lookouts players

- Chicago Cubs players

- Kansas City Athletics coaches

- Kansas City Blues (baseball) managers

- Louisville Colonels (minor league) managers

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Minor league baseball managers

- Montreal Royals managers

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- National League strikeout champions

- National League wins champions

- New York Giants (NL) players

- New York Yankees players

- New York Yankees scouts

- Ottumwa Packers players

- People from St. Croix County, Wisconsin

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- Richmond Colts players

- Rochester Red Wings managers

- St. Louis Cardinals players

- Toronto Maple Leafs (International League) managers