Buzz Aldrin: Difference between revisions

| Line 95: | Line 95: | ||

==UFO claims== |

==UFO claims== |

||

In 2005, while being interviewed for a documentary titled ''First on the Moon: The Untold Story'', Aldrin told an interviewer that they saw an [[unidentified flying object]]. Aldrin |

In 2005, while being interviewed for a documentary titled ''First on the Moon: The Untold Story'', Aldrin told an interviewer that they saw an [[unidentified flying object]]. Aldrin moo |

||

David Morrison, a [[NASA Astrobiology Institute]] Senior Scientist, that the documentary cut the crew's conclusion <!--see my query above-->that they were probably seeing one of four detached spacecraft adapter panels. Their [[S-IVB]] upper stage was 6,000 miles away, but the four panels were jettisoned before the S-IVB made its separation maneuver so they would closely follow the Apollo 11 spacecraft until its first midcourse correction.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://history.nasa.gov/alsj/a11/A11_MissionOpReport.pdf|title=Apollo 11 Mission Op Report|format=PDF}}</ref> When Aldrin appeared on ''[[The Howard Stern Show]]'' on August 15, 2007, [[Howard Stern|Stern]] asked him about the supposed UFO sighting. Aldrin confirmed that there was no such sighting of anything deemed extraterrestrial, and said they were and are "99.9 percent" sure that the object was the detached panel.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://nai.arc.nasa.gov/astrobio/astrobio_detail.cfm?ID=1568|title=NASA Ask an Astrobiologist}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ufoevidence.org/cases/case592.htm |title=Site containing a transcript of the UFO segment of the Untold Story documentary}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://science.discovery.com/tvlistings/episode.jsp?episode=0&cpi=115678&gid=0&channel=SCI |title=A link to The Science Channel scheduling info for cited documentary containing Aldrin's UFO comments}}</ref> |

|||

Interviewed by the [[Science Channel]], Aldrin mentioned seeing unidentified objects, and according to Aldrin his words were taken out of context; he asked the Science Channel to clarify to viewers he did not see alien spacecraft, but they refused.<ref name="SkepticalInquirer">{{cite journal| journal = Skeptical Inquirer| volume = 33| issue = 1| year = 2009| pages = 30–31| title = UFOs and Aliens in Space| last = Morrison| first = David| url = | accessdate = }}</ref> |

Interviewed by the [[Science Channel]], Aldrin mentioned seeing unidentified objects, and according to Aldrin his words were taken out of context; he asked the Science Channel to clarify to viewers he did not see alien spacecraft, but they refused.<ref name="SkepticalInquirer">{{cite journal| journal = Skeptical Inquirer| volume = 33| issue = 1| year = 2009| pages = 30–31| title = UFOs and Aliens in Space| last = Morrison| first = David| url = | accessdate = }}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:23, 25 September 2012

Buzz Aldrin | |

|---|---|

Aldrin portrait for the Apollo 11 mission | |

| Born | January 20, 1930 |

| Status | Retired |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Fighter pilot |

| Space career | |

NASA Astronaut | |

| Rank | Colonel, USAF |

Time in space | 12 days, 1 hour and 52 minutes |

| Selection | 1963 NASA Group |

Total EVAs | 4 |

Total EVA time | 8 hours 4 minutes |

| Missions | Gemini 12, Apollo 11 |

Mission insignia | |

This article may have too many links. (August 2012) |

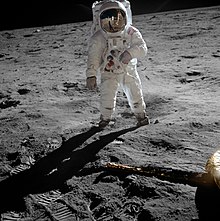

Edwin Eugene "Buzz" Aldrin, Jr. (born January 20, 1930) is a retired American astronaut who was the lunar module pilot on Apollo 11, the first manned lunar landing in history. On July 20, 1969, he was the second human being to set foot on the Moon, following mission commander Neil Armstrong. He is also a retired United States Air Force pilot.

Early life

Aldrin was born in Glen Ridge, New Jersey,[1][2] to Edwin Eugene Aldrin, Sr., a career military man, and his wife Marion (née Moon).[3][4] He is of Scottish, Swedish,[5] and German ancestry. After graduating from Montclair High School in 1946,[6] Aldrin turned down a full scholarship offer from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and went to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York. The nickname "Buzz" originated in childhood: the younger of his two elder sisters mispronounced "brother" as "buzzer", and this was shortened to Buzz. Aldrin made it his legal first name in 1988.[7]

Military career

Aldrin graduated third in his class at West Point in 1951, with a bachelor of science degree in mechanical engineering. He was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force and served as a jet fighter pilot during the Korean War. He flew 66 combat missions in F-86 Sabres and shot down two Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 aircraft. The June 8, 1953, issue of Life magazine featured gun camera photos taken by Aldrin of one of the Russian pilots ejecting from his damaged aircraft.[8]

After the war, Aldrin was assigned as an aerial gunnery instructor at Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, and next was an aide to the dean of faculty at the United States Air Force Academy, which had recently begun operations in 1955. He flew F-100 Super Sabres as a flight commander at Bitburg Air Base, Germany in the 22d Fighter Squadron. In 1963 Aldrin earned a doctor of science degree in astronautics from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His graduate thesis was "Line-of-sight guidance techniques for manned orbital rendezvous",[9] the dedication of which read, "In the hopes that this work may in some way contribute to their exploration of space, this is dedicated to the crew members of this country’s present and future manned space programs. If only I could join them in their exciting endeavors!" On completion of his doctorate, he was assigned to the Gemini Target Office of the Air Force Space Systems Division in Los Angeles before his selection as an astronaut. His initial application to join the astronaut corps was rejected on the basis of having never been a test pilot; that prerequisite was lifted when he re-applied and was accepted into the third astronaut class.

NASA career

Aldrin was selected as part of the third group of NASA astronauts selected in October 1963. Because test pilot experience was no longer a requirement, this was the first selection for which he was eligible. After the deaths of the original Gemini 9 prime crew, Elliot See and Charles Bassett, Aldrin and Jim Lovell were promoted to back-up crew for the mission. The main objective of the revised mission (Gemini 9A) was to rendezvous and dock with a target vehicle, but when this failed, Aldrin improvised an effective exercise for the craft to rendezvous with a coordinate in space. He was confirmed as pilot on Gemini 12, the last Gemini mission and the last chance to prove methods for EVA. Aldrin set a record for extra-vehicular activity, demonstrating that astronauts could work outside spacecraft.

On July 20, 1969, he became the second astronaut to walk on the Moon keeping his record total EVA time until that was surpassed on Apollo 14. There has been much speculation about Aldrin's desire at the time to be the first astronaut to walk on the Moon.[10] According to different NASA accounts, he had originally been proposed as the first to step onto the Moon's surface, but due to the physical positioning of the astronauts inside the compact lunar landing module, it was easier for the commander, Neil Armstrong, to be the first to exit the spacecraft.

Aldrin, a Presbyterian, was the first person to hold a religious ceremony on the Moon. After landing on the Moon, he radioed Earth: "I'd like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours, and to give thanks in his or her own way." He gave himself Communion on the surface of the Moon, but he kept it secret because of a lawsuit brought by atheist activist Madalyn Murray O'Hair over the reading of Genesis on Apollo 8.[11] Aldrin, a church elder, used a pastor's home Communion kit given to him by Dean Woodruff and recited words used by his pastor at Webster Presbyterian Church.[12][13] Webster Presbyterian Church, a local congregation in Webster, Texas, (a Houston suburb near the Johnson Space Center) possesses the chalice used for communion on the Moon, and commemorates the event annually on the Sunday closest to July 20.[14] Aldrin, a Freemason, also carried to the Moon a special deputization from Grand Master J. Guy Smith, with which to claim Masonic territorial jurisdiction over the Moon on behalf of the Grand Lodge of Texas.[15]

Retirement

After leaving NASA, Aldrin was assigned as the Commandant of the U.S. Air Force Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California. In March 1972, Aldrin retired from active duty after 21 years of service, and returned to the Air Force in a managerial role, but his career was blighted by personal problems. His autobiographies Return To Earth, published in 1973, and Magnificent Desolation, published in June 2009, both provide accounts of his struggles with clinical depression and alcoholism in the years following his NASA career.[16] His life improved considerably when he recognized and sought treatment for his problems, and with his marriage to Lois Driggs Cannon. Since retiring from NASA, he has continued to promote space exploration, including producing a computer strategy game called Buzz Aldrin's Race Into Space (1993). To further promote space exploration, and to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the first lunar landing, Aldrin teamed up with Snoop Dogg, Quincy Jones, Talib Kweli, and Soulja Boy to create the rap single and video, "Rocket Experience", with proceeds from video and song sales to benefit Aldrin's non-profit foundation, ShareSpace.[17] In 1995, he made a featured appearance in the Charlton Heston, Mickey Rooney, Deborah Winters film America: A Call to Greatness, directed by Warren Chaney.[18][19]

He referred to a "Phobos monolith" in a July 22, 2009, interview with C-Span: "We should go boldly where man has not gone before. Fly by the comets, visit asteroids, visit the moon of Mars. There's a monolith there. A very unusual structure on this potato shaped object that goes around Mars once in seven hours. When people find out about that they're going to say 'Who put that there? Who put that there?' The universe put it there. If you choose, God put it there…"[20]

Aldrin has voiced parody versions of himself in two of Matt Groening's animated series: The Simpsons episode Deep Space Homer and the Futurama episode "Cold Warriors".

In 2011 Aldrin appeared as himself in the film Transformers: Dark of the Moon.

Aldrin also lent his voice talents to the 2012 video game Mass Effect 3, playing a stargazer who appears in the game's final scene.

Aldrin Cycler

In 1985, Aldrin proposed the existence of a special spacecraft trajectory now known as the Aldrin cycler.[21][22] A spacecraft traveling on an Aldrin cycler trajectory would pass near the planets Earth and Mars on a regular (cyclic) basis. The Aldrin cycler is an example of a Mars cycler. He was also instrumental in the idea of training of astronauts underwater in order to better prepare them for the intricate space walks and duties of maintenance while in space.

Bart Sibrel Incident

On September 9, 2002 Aldrin was lured to a Beverly Hills hotel on the pretext of being interviewed for a Japanese children's television show. When he arrived, Apollo Conspiracy proponent Bart Sibrel accosted him with a film crew and demanded he swear on a Bible that the Moon landings were not faked. After a brief confrontation Aldrin punched Sibrel on the jaw. The police determined that Aldrin was provoked and no charges were filed.[23] Aldrin dedicates a chapter to this incident in his autobiography "Magnificent Desolation".[24]

Criticism of NASA

In December 2003, Aldrin published an opinion piece in The New York Times criticizing NASA's objectives.[25] In it, he voiced concern about NASA's development of a spacecraft "limited to transporting four astronauts at a time with little or no cargo carrying capability" and declared the goal of sending astronauts back to the Moon was "more like reaching for past glory than striving for new triumphs".

Stance on potential causes of global warming

In 2009, Aldrin said he was skeptical that humans were causing current global climate change: "I think the climate has been changing for billions of years. If it's warming now, it may cool off later. I'm not in favor of just taking short-term isolated situations and depleting our resources to keep our climate just the way it is today. I'm not necessarily of the school that we are causing it all, I think the world is causing it."[26]

Books

Books co-authored by Aldrin include Return to Earth (1973), Men From Earth (1989), Reaching for the Moon (2008), Look to the Stars (2009) and Magnificent Desolation (2009). He has also co-authored with John Barnes the science fiction novels Encounter with Tiber (1996) and The Return (2000).

Personal life

Aldrin has been married three times: to Joan Archer, with whom he had three children, James, Janice, and Andrew; to Beverly Zile; and to Lois Driggs Cannon. He filed for divorce from Lois on June 15, 2011, in Los Angeles, citing “irreconcilable differences,” according to his attorney, one day after the couple separated.[27]

His battles against depression and alcoholism have been documented, most recently in Magnificent Desolation.[28][29] Aldrin is an active supporter of the Republican Party, headlining fundraisers for GOP members of Congress.[30] In 2007, Aldrin confirmed to Time magazine that he had recently had a face-lift;[31] he joked that the G-forces he was exposed to in space "caused a sagging jowl that needed some attention."[31]

Honors

- Military decorations include the Air Force Distinguished Service Medal, the Legion of Merit, two awards of the Distinguished Flying Cross, and three awards of the Air Medal.

- NASA decorations include the NASA Distinguished Service Medal, the NASA Exceptional Service Medal, and two awards of the NASA Space Flight Medal.

- Civilian awards and decorations include the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the Robert J. Collier Trophy, the Robert H. Goddard Memorial Trophy, and the Harmon International Trophy.

- Aldrin and his Apollo 11 crewmates were the 1999 recipients of the Langley Gold Medal from the Smithsonian Institution.

- The crater Aldrin on the Moon near the Apollo 11 landing site and Asteroid 6470 Aldrin[32] are named in his honor.

- In 1963, he earned a Doctorate of Science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- In 1967, Aldrin received an Honorary Doctorate of Science from Gustavus Adolphus College.

- In 2001, President Bush appointed Aldrin to the Commission on the Future of the United States Aerospace Industry.[33][34]

- Aldrin received the 2003 Humanitarian Award from Variety, the Children's Charity, which, according to the organization, "is given to an individual who has shown unusual understanding, empathy, and devotion to mankind."[35]

- Aldrin is on the National Space Society's Board of Governors, and has served as the organization's Chairman; an inductee of the Astronaut Hall of Fame; and a member of The Planetary Society, with Aldrin's pre-recorded voice appearing on nearly every episode of the Society's Planetary Radio.

- In 2006, the Space Foundation awarded Aldrin its highest honor, the General James E. Hill Lifetime Space Achievement Award,[36] which is presented annually to recognize outstanding individuals who have distinguished themselves through lifetime contributions to the welfare or betterment of humankind through the exploration, development and use of space, or the use of space technology, information, themes or resources in academic, cultural, industrial or other pursuits of broad benefit to humanity.

- For contributions to the television industry, Aldrin was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at Hollywood and Vine.[37]

- Inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2007.

- In 2009, President Obama signed legislation conferring the Congressional Gold Medal upon Aldrin and his Apollo 11 crewmates, Neil Armstrong and Michael Collins.

- In a 2010 Space Foundation survey, Aldrin was ranked as the #9 (tied with astronauts Gus Grissom and Alan Shepard) most popular space hero.[38]

- In 2011, Aldrin was nominated for Best Cameo at the 2011 Scream Awards for his role playing himself in Transformers: Dark of the Moon.

UFO claims

In 2005, while being interviewed for a documentary titled First on the Moon: The Untold Story, Aldrin told an interviewer that they saw an unidentified flying object. Aldrin moo David Morrison, a NASA Astrobiology Institute Senior Scientist, that the documentary cut the crew's conclusion that they were probably seeing one of four detached spacecraft adapter panels. Their S-IVB upper stage was 6,000 miles away, but the four panels were jettisoned before the S-IVB made its separation maneuver so they would closely follow the Apollo 11 spacecraft until its first midcourse correction.[39] When Aldrin appeared on The Howard Stern Show on August 15, 2007, Stern asked him about the supposed UFO sighting. Aldrin confirmed that there was no such sighting of anything deemed extraterrestrial, and said they were and are "99.9 percent" sure that the object was the detached panel.[40][41][42]

Interviewed by the Science Channel, Aldrin mentioned seeing unidentified objects, and according to Aldrin his words were taken out of context; he asked the Science Channel to clarify to viewers he did not see alien spacecraft, but they refused.[43]

In popular culture

Aldrin has been portrayed by:

- Cliff Robertson in Return to Earth (1976)

- Himself in The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976)

- Himself in The Simpsons (1994)

- Larry Williams in Apollo 13 (1995)

- Xander Berkeley in Apollo 11 (1996)

- Bryan Cranston in From the Earth to the Moon (1998) and Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D (2005)

- Adam Paul in King of the Moon (2004)

- Alex Kreuzwieser in Sea of Tranquility (2008)

- James Marsters in Moonshot (2009)

- Himself and John Anderson in the 30 Rock episode, "The Moms" (2010)

- Mariano Etcheverry in Apollo 11, un pas en fals? (2010)

- Nicolás Gutiérrez in Shoot for the Moon (2011)

- Himself and Cory Tucker in Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011)

- Himself in Futurama (2011)

- Ken Arnold in Men in Black 3 (2012)

- Hugh Davidson (voice) in the Mad episode, "Garfield of Dreams / I Hate My Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" (2012)

- Paul-Henri Campbell poetry book Space Race features a complete cycle on the Apollo program and a five part piece on Buzz Aldrin. (2012)

Monty Python's Flying Circus series 2, episode 4 (episode 17 overall), was entitled "The Buzz Aldrin Show (or: An Apology)" and aired 20 October 1970. Aldrin is referred to in dialogue and the closing credits scroll over his NASA portrait. The episode includes the sketch, "How to Recognize a Mason", mocking Freemasonry, but makes no mention of Aldrin's Masonic membership and activities.

Pixar character Buzz Lightyear's name was inspired by Aldrin.[44] Aldrin acknowledged the tribute when he pulled a Buzz Lightyear doll out during a speech at NASA, to rapturous cheers; a clip of this can be found on the Toy Story 10th Anniversary DVD. Aldrin did not, however, receive any endorsement fees for the use of his first name.[45]

Buzz Aldrin voiced a minor character, the Stargazer, in the epilogue scene of Mass Effect 3.

Jarle Bernhoft named a song after Aldrin in his sophomore album, Solidarity Breaks, in 2010.

References

- ^ Staff. "To the moon and beyond", The Record (Bergen County), July 21, 2009. Accessed July 20, 2009. The source is indicative of the confusion regarding his birthplace. He is described in the article's first paragraph as having been "born and raised in Montclair", while a more detailed second paragraph on "The Early Years" states that he was "born Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. on January 20, 1930, in the Glen Ridge wing of Montclair Hospital".

- ^ Hansen, James R. (2005). First Man: The Life of Neil A. Armstrong. Simon & Schuster. p. 348."His birth certificate lists Glen Ridge as his birthplace."

- ^ BuzzAldrin.com - About Buzz Aldrin

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (June 15, 2009 and June 21, 2009). "Questions for Buzz Aldrin: The Man on the Moon". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Note: nytimes.com print-view software lists the article date as June 21, 2009; main article webpage shows June 15. - ^ From The Dollar To The Moon[dead link]

- ^ "Aldrin Was A Classmate" (PDF). Adirondack Daily Enterprise. July 14, 1969. Retrieved July 17, 2012.

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew. "A Man on the Moon". p. 585.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ Life Magazine June 8, 1953.p.29

- ^ http://dspace.mit.edu/handle/1721.1/12652

- ^ Apollo Expeditions to the Moon, chapter 8, p. 7.

- ^ Chaikin, Andrew. A Man On The Moon. p 204.

- ^ Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Buzz Aldrin, Gene Farmer, Dora Jane Hamblin. First on the Moon — A Voyage with Neil Armstrong, Michael Collins, Edwin E. Aldrin Jr", London: Michael Joseph, 1970, p. 251.

- ^ Hillner, Jennifer (2007-01-24). "Sundance 2007: Buzz Aldrin Speaks". Table of Malcontents - Wired Blogs. Wired. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ "Webster Presbyterian Church History". Retrieved 2009-11-09.

- ^ The Story of Tranquility Lodge No. 2000

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz (2009). Magnificent Desolation: The Long Journey Home from the Moon. Harmony.

- ^ Buzz Aldrin and Snoop Dogg reach for the stars with Rocket Experience, Times Online, June 25, 2009

- ^ America Movie Biographies

- ^ Internet Movie Database

- ^ "Buzz Aldrin Reveals Existence of Monolith on Mars Moon". C-Span. July 22, 2009.

- ^ Aldrin, E. E., "Cyclic Trajectory Concepts," SAIC presentation to the Interplanetary Rapid Transit Study Meeting, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, October 1985.

- ^ Byrnes, D. V., Longuski, J. M., and Aldrin, B.,"Cycler Orbit Between Earth and Mars," Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, Vol. 30, No. 3, May–June 1993, pp. 334-336.

- ^ "Ex-astronaut escapes assult charge". BBC News. 2002-09-21. Retrieved 2012-07-07.

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz (2009). Magnificent Desolation. Harmony Books. p. 281."A Blow Heard 'Round the World".

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz (2003-12-05). "Fly Me To L1". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ Aldrin, Buzz (2009-07-03). "Buzz Aldrin calls for manned flight to Mars to overcome global problems". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

- ^ Roberts, Roxanne and Argetsinger "Love, etc.: Buzz Aldrin divorces; Hugh Hefner gets revenge on ex" (June 16, 2011) The Washington Post

- ^ "After walking on moon, astronauts trod various paths - CNN.com". CNN. July 17, 2009. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ Read, Kimberly (2005-01-04). "Buzz Aldrin". About.com. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ^ http://combatveteransforcongress.org/sites/default/files/2-26-10-invite.pdf

- ^ a b Time article: "10 Questions for Buzz Aldrin."

- ^ "Discovery Circumstances: Numbered Minor Planets (5001)-(10000): 6470 Aldrin". IAU: Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 2008-07-26.

- ^ Personnel Announcements - August 22, 2001 White House Press Release naming the Presidential Appointees for the commission.

- ^ [1] - This source states he was appointed in 2002, although according to the August 22, 2001 Press Release, it was 2001.

- ^ "Variety International Humanitarian Awards". Variety, the Children's Charity. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- ^ Symposium Awards | National Space Symposium

- ^ Aldrin "Hollywood Walk of Fame database". HWOF.com.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "Space Foundation Survey Reveals Broad Range of Space Heroes".

- ^ "Apollo 11 Mission Op Report" (PDF).

- ^ "NASA Ask an Astrobiologist".

- ^ "Site containing a transcript of the UFO segment of the Untold Story documentary".

- ^ "A link to The Science Channel scheduling info for cited documentary containing Aldrin's UFO comments".

- ^ Morrison, David (2009). "UFOs and Aliens in Space". Skeptical Inquirer. 33 (1): 30–31.

- ^ "Toy Story 3 Featurette - Buzz Lightyear". Trailer Addict. 2010-06-18. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (June 15, 2009 and June 21, 2009). "Questions for Buzz Aldrin: The Man on the Moon". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Note: nytimes.com print-view software lists the article date as June 21, 2009; main article webpage shows June 15.

External links

- Official website

- Buzz Aldrin's Official NASA Biography

- A February 2009 BBC News item about Buzz Aldrin's Moon memories, looking forward to the 40th anniversary of the first Moon landing

- "Satellite of solitude" by Buzz Aldrin: an article in which Aldrin describes what it was like to walk on the Moon, Cosmos science magazine

- Video interview with Buzz Aldrin Buzz is shown an enlarged print of Tranquility Base and talks Graeme Hill through the points of significance.

- Video interview on AstrotalkUK

- Articles with too many wikilinks from August 2012

- 1930 births

- Living people

- 1966 in spaceflight

- 1969 in spaceflight

- American astronauts

- Apollo program astronauts

- People who have walked on the Moon

- United States Air Force astronauts

- United States Astronaut Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Essex County, New Jersey

- American people of German descent

- American people of Scottish descent

- American people of Swedish descent

- American Presbyterians

- Freemasons

- United States Military Academy alumni

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology alumni

- United States Air Force officers

- American military personnel of the Korean War

- American aviators

- Aviators from New Jersey

- National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees

- Participants in American reality television series

- People self-identifying as alcoholics

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Congressional Gold Medal recipients

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Medal (United States)

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- Recipients of the Distinguished Flying Cross (United States)

- Recipients of the Air Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Distinguished Service Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Exceptional Service Medal

- Recipients of the NASA Space Flight Medal

- Recipients of the Cullum Geographical Medal

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Harmon Trophy winners

- Great Medal of the Aéro-Club de France winners

- Recipients of the Langley Medal