Camino de Santiago (route descriptions)

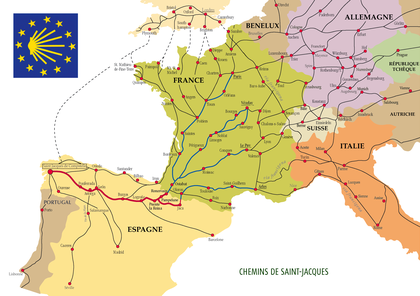

The Camino de Santiago, also known as the Way of St. James, extends from different countries of Europe, and even North Africa, on its way to Santiago de Compostela and Finisterre. The local authorities try to restore many of the ancient routes, even those used in a limited period, in the interest of tourism.

Here follows an overview of the main routes of the modern-day pilgrimage.

UNESCO World Heritage Listings[edit]

The Routes of Northern Spain and the French Way (Camino Francés) are the ones listed in the World Heritage List by UNESCO.[1]

Camino Francés[edit]

The French Way (Spanish: Camino Francés) is the most popular of the routes. It runs from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port on the French side of the Pyrenees to Roncesvalles on the Spanish side before making its way through to Santiago de Compostela through the major cities of Pamplona, Logroño, Burgos and León.

Routes of Northern Spain[edit]

The Routes of Northern Spain is a network of four Christian pilgrimage routes in northern Spain.

Camino Primitivo[edit]

The Camino Primitivo splits off from the Norte south of Villaviciosa, near Oviedo, and spans 355 km (this includes roughly 40 km on the Camino Francés at the end). As the name suggests, this is one of the original Caminos.

Northern Way[edit]

The Northern Way (Spanish: Camino del Norte) (also known as the "Liébana Route") is an 817 km, five-week coastal route from Basque Country at Irún, near the French border, and follows the northern coastline of Spain to Galicia where it heads inland towards Santiago joining the Camino Francés at Arzúa. This route follows the old Roman road, the Via Agrippa, for some of its way and is part of the Coastal Route (Spanish: Ruta de la Costa). This route was used by Christian pilgrims when Muslim domination had extended northwards and was making travel along the Camino francés dangerous.[2]

The route passes through San Sebastian, Guernica, Bilbao, and Oviedo. It is less populated, lesser known and generally more difficult hiking. Shelters are 20 to 35 kilometers apart, rather than there being hostels (Spanish: albergues) or monasteries every four to ten kilometers as on the Camino Francés.

The Coastal Way links with the French Way through the Liébana Route.[3]

Tunnel Way[edit]

The Tunnel Way is also known as the Tunnel Route, the Basque Inland Route and the San Adrian Route. In the Early Middle Ages, when the Northern (Coastal) Way was subject to the Vikings' skirmishes and Muslim presence and forays threatened pilgrims and trade routes in the borderlands, the Tunnel Way provided a safe road north of the frontier area, i.e. Gipuzkoa and Alava. This may be the oldest and most important stretch of the Way of St. James up to its heyday in the 13th century. From the starting point in Irún, the road heads south-west up the Oria valley (Villabona, Ordizia, Zegama), reaches its highest point at the San Adrian tunnel and runs through the Alavan plains (Zalduondo, Salvatierra/Agurain, Vitoria-Gasteiz and Miranda de Ebro). Yet previous to the latter, nowadays pilgrims usually take a detour south towards Haro and on to Santo Domingo de la Calzada on account of its better provision.

In Spain and Portugal[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

The following routes to Santiago can be traced on the Iberian Peninsula.

Portuguese Way[edit]

The Portuguese Way (Spanish: Camino Portugués, Portuguese: Caminho Português) begins at Lisbon or Porto in Portugal.[4] From Porto, along the Douro River, pilgrims travel north crossing the Ave, Cávado, Lima and Minho rivers before entering Spain and then passing through Padron before arriving at Santiago. It is the second most popular way, after the French one. The route is 610 km long starting in Lisbon or 227 km long starting in Porto. From Lisbon, the starting point is Lisbon Cathedral, crossing the Thermal Hospital of Caldas da Rainha (1485) and heading to the Alcobaça Monastery (1252), which was an albergue (hostel) for medieval pilgrims who could only stay there for a single night. Using Roman roads, pilgrims headed to Coimbra and had to reach Porto before night falls, as the gates of the city closed, once in the pilgrims headed to Church of São Martinho de Cedofeita (c. 1087).

There are two traditional routes from Porto, one inland (the Central Way) and the Coastal Way (Caminho da Costa). Rates is considered a central site of the Portuguese Way.[5] The way has been used since the Middle Ages and the ancient monastery of Rates (rebuilt in 1100) gained importance due to the legend of Saint Peter of Rates. The legend holds that Saint James ordained Peter as the first bishop of Braga in the year AD 44. Peter died as a martyr while attempting to convert local pagans.

Rates is also the location of the first modern pilgrim hostel (Albergue) in the Portuguese way.[6] On the way to the Rates Monastery there is the medieval Dom Zameiro Bridge. It was (re)built in 1185 for an easy cross of the Ave river by medieval pilgrims. It is part of Roman Via Veteris and known in the Middle Ages as Karraria Antiqua (the old way), as such the bridge has Roman origin.[7] After leaving the monastery, the crossing of Cávado River was made using barges landing in Barca do Lago, which literally means "Lake's barge". The Brotherhood of Barca do Lago stated in 1635: "this passage is very popular and it is for more than 400 years in our peaceful possession". The Portuguese King Sancho II made the crossing there during a pilgrimage in 1244 and centuries later King Manuel I did the same in 1502. Currently, the crossing which replaces the barges in both the Coastal and the Coastal derivation of the central way is made through Ponte de Fão, built in 1892, heading to the Neiva Castle, currently lost, the Neiva was a Castro culture hillfort and early medieval castle. For pilgrims preferring the inland route, the crossing is made through the Medieval Bridge of Barcelos, constructed between 1325 and 1328.

The crossing of the Lima River is made through the Eiffel bridge (1878) in the Coastal way, originally via barges. The bridge and the town of Viana do Castelo are signed by the sighting of the Monument-Temple of Santa Luzia (1904) over a hilltop. The Lantern tower of the sanctuary is where the pilgrim can see most of one's route in one of the most iconic views of Northern Portugal. Pilgrims were treated in the Old Hospital of Viana do Castelo, an hostel for pilgrims from early 15th century. For the inland route, Ponte de Lima's bridge is used. The later bridge possibly dates to the 1st century and was rebuilt in 1125. One of the most tiring parts of the Portuguese inland Way is in the Labruja hills in Ponte de Lima, which are hard to cross. In Classical antiquity, the Lima was said to have properties of memory loss due to events in an ancient battle there between the Turduli and the Celts. Strabo compared it to the mythological Lethe, the river of unmindfulness. Two ancient canoes found in Lanheses (Viana do Castelo) and the itinerary of the Loca Maritima Roman way suggest that to be the site where the Roman soldiers were fearful of the crossing during the conquest of the region in 136 BC.[8]

The Coastal Way gained prominence in the 15th century due to the growing importance of the coastal towns in the advent of the Age of Discovery. After leaving Porto, the route splits from the central way in the countryside of Vila do Conde. The town is still today crowned by the Monastery of Santa Clara (1318). The town is noted for the austere Gothic and lavish Late Gothic architecture, with the Matriz Church of Vila do Conde being built by king Manuel I of Portugal while in pilgrimage. The rising importance of Póvoa de Varzim imposed this new direction,[9] In Póvoa de Varzim, the small Saint James Chapel (1582) in Praça da República holds a 15th century icon of Saint James found at the beach, the way follows west to the beach, heading to Esposende, Viana do Castelo and Caminha before reaching the Spanish border.

A contemporary version of the Coastal Way, pushed by German pilgrims, goes through Northern Portugal continuously along the sea, using beach walkways. This version of the Coastal Way, also referred to as the Senda Litoral, is gaining importance, as the traditional route is increasingly urbanized and the new version is considered by some pilgrims to be more pleasant. Just before the crossover into Spain, there is also a 2-3 day detour from the Coastal Way called the Spiritual Detour (variante espiritual) known for solitude and beauty.[10][11]

The Camino winds its way inland until it reaches the Spanish border at the Minho river through Valença, heading for a 108 km walk to Santiago, passing through Tui.

A less-travelled Portuguese route, the Caminho Português Interior, begins at either the village of Farminhão or the adjacent city of Viseu, and continues along the Douro river valley via Lamego, Chaves, and Verín before connecting with the Via de la Plata at Ourense. Waymarking along this route, some 420 km in total, is intermittent until the Spanish border.

Aragonese Way[edit]

The Aragonese Way (Spanish: Camino Aragonés) comes down from the Somport pass in the Pyrenees and makes its way down through the old kingdom of Aragon. It follows the River Aragón passing through towns such as Jaca. It then crosses into the province of Navarre to Puente La Reina where it joins the Camino Francés.

English Way[edit]

The English Way (Spanish: Camino Inglés) is traditionally for pilgrims who traveled to Spain by sea and disembarked in Ferrol or A Coruña. These pilgrims then made their way to Santiago overland. It is so called because most of these pilgrims were English though some came from all points in northern Europe.

Camino Mozárabe and the Via de La Plata[edit]

Sometimes incorrectly known in English as the Silver Route or Way - "Plata" is a corruption of the Arabic word balath, meaning paved road.

The Via de La Plata (once a Roman causeway joining Italica and Asturica Augusta) starts in Seville from where it goes north to Zamora via Zafra, Cáceres and Salamanca. It is much less frequented than the French Way or even the Northern Way - in 2013, of the 215,000 pilgrims being granted the compostela in Santiago, 4.2% traveled on the Via de la Plata, compared to 70.3% on the Camino Francés.[12] After Zamora there are three options. The first route, or Camino Sanabrés heads west and reaches Santiago via Ourense. Another route continues north to Astorga, from where pilgrims can continue west along the Camino Francés to Santiago. A third, seldom traveled route, crosses into Portugal and passes through Bragança, rejoining the Camino Sanabrés near Ourense.

The Camino Mozárabe route (also known as the Camino Sanabrés), from Almeria, Granada or Málaga, passes through Córdoba and later joins up with the Via de La Plata at Mérida.

Camino de Madrid[edit]

The Camino de Madrid goes northwards from Madrid, through Segovia and near Valladoid, joining the Camino Francés at Sahagún.

Camino del Ebro[edit]

The Camino del Ebro starts in Catalonia at Sant Jaume d'Enveja near Deltebre, where Saint James is traditionally supposed to have left Spain on his way home to martyrdom in Palestine, and follows the River Ebro past Tortosa and Zaragoza, joining the Camino Francés at Logroño.

Camino de Santiago de Soria[edit]

Sometimes known as the Camino Castellano-Aragonés, this camino leaves the Camino del Ebro at Gallur and goes past Soria to Santo Domingo de Silos, where it joins the Camino de la Lana.

Camino de la Lana[edit]

The Camino de la Lana (sometimes Ruta de la Lana), or wool road, leaves Alicante and heads mainly northwards for 670 km, joining the Camino Francés at Burgos.

Camino de Levante[edit]

The Camino de Levante starts at Valencia and crosses Castille-La Mancha, passing through towns and cities including Toledo, El Toboso, Ávila and Medina del Campo, joining the Via de la Plata at Zamora.

Camino del Sureste[edit]

The Camino del Sureste starts at Alicante and follows a broadly similar route as the Camino del Levante from Albacete until Medina del Campo, where the routes bifurcate, with the Sureste heading northwards to Tordesillas, joining the Via de la Plata at Benavente, while the Levante goes westwards to Toro and Zamora.

Camino de Torres[edit]

The Camino de Torres starts in Salamanca, goes past Ciudad Rodrigo, crosses the Portuguese border near Almeida, continues past Braga and joins the Camino Portugués at Ponte de Lima.

Camino de Invierno[edit]

275 km long, this route leaves the French Way at Ponferrada and bypasses O Cebreiro, instead routing through Quiroga, Monforte de Lemos and Lalín before joining the Vía de la Plata at A Laxe. Traditionally, pilgrims used this way to avoid the snows of O Cebreiro in wintertime, from which its name derives. It was officially recognised as one of the valid routes for obtaining the Compostela in 2016. This route is unique, as it passes through all four provinces of Galicia: Ourense, Lugo, Pontevedra, and A Coruña.

In France[edit]

The Way of St. James is said to have originated in France, where it is called Le Chemin de St. Jacques de Compostelle. This is the reason that the Spanish themselves refer to the Way of St. James as "the French road", since most of the pilgrims they saw were French. The origin of the pilgrimage is most often cited as the Codex Calixtinus, which is decidedly a French document. Though in the Codex everyone was called upon to join the pilgrimage, there were four main starting points in the Cathedral cities of Tours, Vézelay, Le Puy-en-Velay and Arles. They are today all routes of the Grande Randonnée network.

Paris and Tours route[edit]

The Paris and Tours route (Via Turonensis) used to be the pilgrimage of choice for inhabitants of the Low Countries and those of northern and western France. As other routes are becoming overcrowded, that route is gaining favor, owing to the religious and touristic aspects of the monuments on the way.

One starting point is at the Tour St Jacques in Paris and then on to Orléans-Tours or Chartres-Tours. From Tours, the route passes through Poitiers and Bordeaux, the forest at Les Landes before connecting to the Camino Francés, the national trail GR 65, near Ostabat,[13] shortly before Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port or to the Camino de la Costa in Irún.

Vézelay route[edit]

The Vézelay route passes through Limoges and joins the GR 65 near Ostabat.[13]

Le Puy route[edit]

The Le Puy route (Latin: Via Podiensis, French: route du Puy) is traveled by pilgrims starting in or passing through Le Puy-en-Velay. It passes through Conques, Cahors and Moissac before coming to Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. It is part of GR 65.

Arles Way[edit]

The Arles Way (French: La voie d'Arles or Chemin d'Arles) in southern France, named after that principal cathedral city goes through Montpellier, Toulouse and Oloron-Sainte-Marie before reaching the Spanish border at Col de Somport in the high Pyrenees. It is also called the Via Tolosana, a name that follows the Latin convention of the other French routes, because it passes through Toulouse, a notable pilgrimage destination in its own right. After passing the Pyrenees it is referred to as the Aragonese Way. It is the only French route not to connect to the Camino Francés at Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port. After taking its Aragonese name, it joins the Camino Francés at Puente la Reina.

In Belgium and the Netherlands[edit]

The Way of St. James in the Netherlands is said to have started after St. Boniface brought Christendom to Friesland and the worship of his reliquaries near Dokkum gained popularity from 800 onwards. The route did not become popular however until the 15th century, well after the Santiago Matamoros legend. There are several Cathedral towns considered official starting routes by the Dutch confraternity of St. James. Haarlem, a centuries-old starting point, has been the starting point of a modern cycling route to Santiago de Compostela since 1983, when an international workgroup of scholars researched the old route and one of them developed a set of maps. Since that time there have been other cycling routes to Santiago de Compostela published from other Dutch cities, most notably Maastricht. The Dutch and northern (Flemish) Belgians call the route the Jacobsroute. In Wallonia (southern Belgium) it is called Le Chemin de St. Jacques de Compostelle.

Another Dutch long distance path, the Pelgrimspad (Pilgrims' Path), leads from Amsterdam to Visé in Belgium (about 100 km from Namur), and may have been a route for St. James pilgrims departing from Amsterdam connecting to one of the main routes at Vézelay. Another ancient route can be traced through Ghent (note the scallop on the Pilgrims hat in bottom right panel of the Ghent Altarpiece) and Amiens to connect to Paris and the Via Turonensis, one of the four main French routes.

It is a mistake to assume that medieval pilgrims were only focussed on one goal. Most St. James pilgrims through the centuries stopped to visit other famous reliquaries, and many of the most popular ones in France and northern Spain are listed in the Codex. Many had both a scallop shell and a palm frond in their possession, indicating that they had been or were on their way to both Rome and Santiago de Compostela.

In Germany[edit]

The paths in Germany are collectively named "Wege der Jakobspilger". Other names that can be seen on trail markings are "Jakobsweg" and "Jakobspilgerweg". The German Way of St. James routes are maintained by numerous non-profit organizations. Their aim is, among others, to make the pilgrimage experience qualitative and authentic.

One section of the Way of St. James runs through the German states of Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia and Hesse following the course of the historic trade route, the Via Regia from Görlitz via Bautzen, Kamenz, Großenhain, Wurzen, Leipzig, Merseburg, Naumburg (Saale), Erfurt, Gotha, Eisenach and Vacha to Fulda. It has a length of 500 km. On 6 July 2003 the first section to Erfurt was opened in Königsbrück. The opening of the second section followed on 11 October 2003 in Vacha. The section along the historic "Via Regia" is also called the Ecumenical Pilgrims' Way (Ökumenischer Pilgerweg).

Providing the link to Franconia, the Saxon Way of St. James on the Franconian Road (Sächsische Jakobsweg an der Frankenstraße) runs from Königsbrück via Wilsdruff to Grumbach (old roadbed until the 15th century) and from Bautzen via Bischofswerda, Dresden, Kesselsdorf, Grumbach, through the Tharandt Forest to Freiberg and on to Chemnitz and Zwickau, in order to join the Via Imperii coming from Leipzig, before continuing via Plauen, Hof and Bayreuth to Nuremberg. The signage was carried out in 2009-13. Between Wilsdruff and Grillenburg in the Tharandt Forest it runs in the same ancient route corridor as the Holy Way from Bohemia to Meißen, which is also being revived.

The Lahn-Rhine-Camino can be followed since 2001 and is maintained by the non-profit organization St. Jakobus-Gesellschaft Rheinland-Pfalz-Saarland e.V. since 2005. The route starts in the central part of Germany, coming from the north-east, and continues in a south-western direction. Numerous artefacts along the path provide information about earlier pilgrimages. The trail consists of two sections, the Lahn-Camino, which was updated in 2018/19 and re-signposted along the way, and the Rhine-Camino. With a total length of 190 kilometres, the trail crosses the federal state of Hesse, where it originates, and ends in Rhineland-Palatinate. Starting in Wetzlar, the route first passes through Hessian towns and villages to Weilburg. From Weilburg, the route leads via Villmar to Diez. Once in Diez, the following stages are Obernhof and then Bad Ems. The Lahn-Camino meets the Rhine-Camino in Lahnstein, from where the route follows the Rhine to Kamp-Bornhofen. From there, another 15 kilometres have to be overcome to Sankt Goarshausen, until one finishes the Rhine-Camino by arriving in Korb. Here, one has the option to continue their way towards Trier or Worms, two of the oldest cities in Germany.[14][15]

In Switzerland[edit]

The Way of St. James is also known as Jakobsweg in Switzerland and the route in Switzerland is the Via Jacobi. Many routes originating in Scandinavia, Germany, Austria, Eastern Europe and even Italy/South Tyrol led to Switzerland and from there to France. Beginning in the early Middle Ages (9-10th century), pilgrims coming from northern and eastern Europe crossed into Switzerland at the Lake of Constance and journeyed across the country to Geneva at the French border. As they wandered through the countryside, the pilgrims passed by three traditional pilgrimage places, Einsiedeln Abbey, Flüeli Ranft and the Caves of Saint Beatus. They also traveled through historic cities and villages, including St. Gall, Lucerne, Schwyz, Interlaken, Thun, Fribourg, and Lausanne. Today the original paths have been restored and the Via Jacobi is an integral part of the European Way of St. James.

In Ireland[edit]

St. James's Gate in Dublin was traditionally a principal starting point for Irish pilgrims to begin their journey on the Camino de Santiago (Way of St. James).[16] The pilgrims' passports were stamped here before setting sail, usually for A Coruña, north of Santiago. It is still possible for Irish pilgrims to get these traditional documents stamped at St James' Church, and many do, while on their way to Santiago de Compostella.

In Lithuania[edit]

Lithuanian section[17] of the Way of Saint James is called "Camino Lituano" (official name: "Camino Lituano kultūros kelias"). The main Camino Lituano route is 500 km long. The route starts at Žagarė near Latvian ant Lithuanian border, runs through Šiauliai, Kaunas, Alytus counties and ends at Sejny in Poland, where it connects to the "Camino Polaco" route. [18]

It has two other sections in Lithuanian regions (Aukštaitija and Samogitia), by which the main route can be reached.[19][20]

In Poland[edit]

- From Sandomierz to Kraków is the Lesser Poland Way

- From Gniezno to Poznań, Leszno, Wschowa and Głogów is the Greater Poland Way

- From Głogów to Zgorzelec and Görlitz is the Lower Silesian Way

- From Lithuania via Olsztyn, Toruń, Poznań and Słubice is the Camino Polacco

- From Kretinga via Elbląg and Gdańsk to Szczecin is the Camino Polacco del Norte and Pomeranian way of St. James

- From Jelenia Góra to Lubań is the Via Cervimontana

- From Kraków to the Czech Republic is the Silesian-Moravian Way

- From Korczowa/Pilzno via Kraków to Görlitz is the Via Regia

- From Kraków to the Levoča in Slovakia is known as Spišská Jakubská cesta SK

In Slovakia[edit]

The Slovak section of the Way of Saint James is called Svätojakubská cesta (official name: Svätojakubská cesta na Slovensku).[21] Another name that can sometimes be seen on trail markings is Jakubská cesta.

The main route in Slovakia begins in Košice, in front of St Elisabeth Cathedral, and ends in Bratislava, on SNP Square.[22] The whole route spans over 620 km and can be finished in approximately 30 days.[22]

In Malta[edit]

In 1602, Grandmaster Alof de Wignacourt provided instructions of safe passage (a credencial) to Don Juan Benegas from St. Paul’s Grotto, Rabat, to visit holy places in Europe including Saint James In Galicia (as noted in a In a Liber Bullarum entry of the early 17th century).[23] [24]

The Camino Maltés route is around 3,600 km long, and connects Malta to Sicily (through Il Cammino di San Giacomo in Sicilia), Sardinia (through the Cammino di Santu Jacu), Barcelona (Camino Catalán) and eventually Santiago de Compostela. [25] [26] [27]

The Maltese segment of the Camino Maltés route is approximately 35 km long. It begins at Saint Paul's Grotto, the place where Maltese tradition says that Saint Paul spent his three-month stay on the island after his shipwreck on the Maltese coast. [28] In Malta, the Camino Maltés meets another ancient pilgrim route, now known as the Universal Peace Walk (between Mdina and Żejtun). [23] The Maltese segment of the Camino Maltés concludes in Valletta, where pilgrims catch the ferry to Sicily. [24]

References[edit]

- ^ "Routes of Santiago de Compostela: Camino Francés and Routes of Northern Spain", UNESCO

- ^ ""Los Caminos del Norte", The confraternity of Saint James". Archived from the original on 2019-01-31. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

- ^ "The Way of St. James", the Cantabrian film commission

- ^ The Confraternity of Saint James. "The Camino Portugués". Archived from the original on 2016-06-30. Retrieved 2016-05-17.

- ^ Costa, António Carvalho da (1706). "Da Villa de Rates". Corografia portugueza e descripçam topografica do famoso reyno de Portugal (in Portuguese). Vol. I. Lisbon: Valentim da Costa Deslandes. pp. 336–337.

- ^ David Samuel. "Albergue de Peregrinos de Rates, no caminho Português de Santiago".

- ^ "Ponte D. Zameiro e Azenhas". DGPC. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ "O Rio Lethes e o Lugar da Passagem". Paço de Lanheses. Retrieved January 3, 2017.

- ^ "Caminho de Santiago - Caminho Português da Costa". Câmara Municipal de Vila do Conde. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ^ Pinto, Luísa. "Alemães empurram Caminho de Santiago para junto do mar" (in Portuguese). Público. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ Ich bin dann mal weg: meine Reise auf dem Jakobsweg (in German). München: Malik. ISBN 978-3-89029-312-7. In English, I'm off then: My journey along the Camino de Santiago. New York: Free Press. 2009. ISBN 978-1-4165-5387-8.

- ^ "2013 Pilgrim statistics from Santiago Cathedral" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2015-06-12.

- ^ a b The Confraternity of Saint James. "Overview: The Vézelay Route". Archived from the original on 2009-03-27.

- ^ Schäfer, Karl-Josef (2009). Der Jakobsweg - Wetzlar nach Lahnstein (in German) (3. ed.). Norderstedt: Books on Demand. ISBN 978-3-8334-9475-8.

- ^ Scholz, Wolfgang (2019). Outdoor – Der Weg ist das Ziel, Lahn-Camino und Rhein-Camino (in German) (1. ed.). Welver: Conrad Stein Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86686-617-1.

- ^ "Camino de Santiago and St. James’s Gate", Guinness Storehouse

- ^ "Dėl Šv. Jokūbo kelio per Lietuvą", Lietuvos Respublikos teisės aktų registras

- ^ "Apie Camino Lituano", CaminoLituano.com

- ^ "Camino Lituano Žemaitijos atšakos etapai", CaminoLituano.com

- ^ "Camino Lituano Aukštaitijos atšakos etapai", CaminoLituano.com

- ^ Občianske združenie Priatelia Svätojakubskej cesty na Slovensku – Camino de Santiago. "Svätojakubská cesta na Slovensku (Way of Saint James in Slovakia)" (in Slovak). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ a b Občianske združenie Priatelia Svätojakubskej cesty na Slovensku – Camino de Santiago. "Svätojakubské trasy na Slovensku (Routes of the Way of Saint James in Slovakia)" (in Slovak). Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- ^ a b "XirCammini Projects". XirCammini. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ a b Santiago, Federación Española de Asociaciones de Amigos del Camino de. "Camino de Santiago". Camino de Santiago (in Spanish). Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ "Caminos de Santiago en Europa". National Geographic Institute of Spain. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Camino Maltes". Camino Maltes. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ Esparza, Daniel (2022-12-05). "Malta is now connected to the Way of St. James". Aleteia — Catholic Spirituality, Lifestyle, World News, and Culture. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ^ "St. Paul's Grotto, Rabat, Malta". www.malta.com. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

External links[edit]

- Walking La Via de la Plata - a short video

- Caminos de Santiago

- Explore the Routes of Santiago in the Basque Country in the UNESCO collection on Google Arts and Culture

- Caminho Português, the Way of St. James in Portugal

- Arles route

- The Way of St. James in Eastern Germany

- The Way of St. James in Switzerland

- The Way of St. James in Slovakia

- The Camino Maltés

- Follow the Yellow Shell - A Pilgrims Guide to the Camino routes

- GPS coordinates