Church of St Lawrence, Alton

| Church of St Lawrence, Alton | |

|---|---|

Church of St Lawrence from the north-west | |

| Location | Alton, Hampshire |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | www |

| History | |

| Status | Parish church |

| Founded | c. 1070 |

| Dedication | St Lawrence the Martyr |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Listed building - Grade I |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Norman, Early English, Perpendicular |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Stone |

| Administration | |

| Province | Canterbury |

| Diocese | Winchester |

| Parish | Parish of the Resurrection |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Bishop of Winchester Bishop of Basingstoke |

| Vicar(s) | Revd Andrew Mickelfield, Revd David Hicks |

| Curate(s) | Revd Ian Toombs |

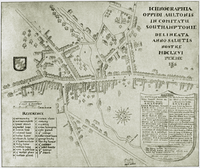

The Church of St Lawrence, Alton is an Anglican parish church in Alton, Hampshire, England. It is a Grade I listed building and is notable both for the range of its architecture and for being the site of the concluding action of the Battle of Alton during the English Civil War.

History

The Church of St Lawrence, like many older English churches, is an amalgam of styles resulting from repeated additions and extensions being made down the centuries. In the words of William Curtis:

There are then apparent in the church three distinct styles of architecture, and these strangely enough represent the two extremes of Gothic architecture, namely, early Norman, early English, and two sorts of Perpendicular and Tudor work, the flat-headed and pointed arch.[1]

Anglo-Saxon

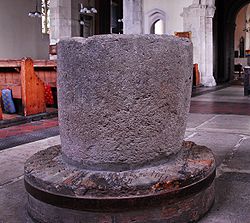

Anglo-Saxon settlement in Alton began in around AD 500 and there was certain to have been a church in the township.[2] There are no remnants of this structure left, except for the baptismal font that is now situated in St Lawrence's.[2] The font is fashioned from one massive block of stone and crude axemarks may be seen on it, showing its primitive workmanship.[2] When the church was restored in 1868 the font was discarded in favour of one of a more contemporary design; it ended up in Cirencester, but was purchased for £10 in 1934 and brought back to St Lawrence's,[2] where it stands at the west end of the south nave on a mill wheel, symbolising Alton's status as a centre of the paper industry. It has been in use as a font since 1950.[2]

Norman

The present-day church had its origins in the Norman period, with building probably starting at some time not long after 1066.[2] The conventional date for the founding of the church is 1070, and the church celebrated its 900th anniversary in 1970. This early church took the shape of a cross, the four Norman arches that formed the tower being described in Pevsner as "emphatically Early Norman, say around 1100".[3] These arches, built of stone probably from Selborne or Binsted,[4] are situated midway down what is now the southern nave, and some remnants of the original door may be seen in the wall behind the 19th-century font located in the centre of the arches.[2] At the top of the pillars supporting the arches are designs fashioned by French craftsmen with axes,[2] including a wolf eating a bone (pictured, left), a pelican, several winged cherubs, a demon and a pair of donkeys.[2]

This Norman church passed to the ownership of William the Conqueror through Edith, the wife of Edward the Confessor, following the Norman Conquest. In the first mention of the church, in a charter of 1087 marked at its foot by William's trademark cross, we read that William exchanged it with the monks of Hyde Abbey in Winchester for their burial ground, upon which he wished to build his new palace.

"The church of Alton, with five hides and tithes, and with other revenues which belonged to the aforesaid church ... And that this gift may be held valid and of perpetual obligation I myself make this mark with my own hand."

— [2]

Alton grew in prosperity during the 12th century as it was on the main route to London from the west country, so it was found necessary to extend the church; it was during this period that what is now the southern nave was extended to the west and building work was also made to the north part of the church. The old west door, which was walled up in the redevelopment of 1868, was built in 1140[5] and Pevsner notes that a southern arcade was added in c. 1140 ("there are faint traces of this arcade inside, i.e. remains of the pier imposts with a band of ornaments").[3] The first known vicar of Alton, also vicar of Colmer and sheriff of Alton, comes from this period, one Richard Turstin, who held the office of Parson from 1161 to 1170.[5]

13th–15th century

Despite the 12th-century extensions, by the 13th century the church was yet again found to be too small, and so the Lady Chapel was built as an extension to the east of the Norman tower. At the eastern end of this chapel niches in the wall were built, at the time containing statues of St Lawrence and the Virgin and Child,[6] but today containing painted wooden statues of St George and St Michael by Mr Southwick.[7]

The well-known Alton Fair started in 1307, following a grant from Edward I; the church grounds were for a while used as a site for commerce and festivities, but on 19 August 1317 the Bishop of Winchester, accompanied by an abbot, two priors and a deacon, hurried to Alton and forbade the holding of fairs "in the churches or cemeteries of the diocese of Winchester, and especially in the church or cemetery of Aulton [sic]".[8] The parishioners of the church were also told

to desist from their errors, to wit, in moving the image of St Lawrence the Martyr, in whose honour the Church there is dedicated, from the high altar, where of approved custom it ought to be, to another place.[8]

This is the first documentary evidence that St Lawrence was the church's patron saint.[8]

The 15th century saw a great number of extension and additions to St Lawrence's, including: the new northern nave – this was of roughly the same proportions as the existing southern nave, and made the church, in Pevsner's words, "essentially a parallelipiped";[3] what was previously the north wall to the old church was demolished and seven arcades were installed in its place, with three paintings of saints (pictured, left) remaining on the northern side of the second pillar from the west; new roofs over both naves; windows recast in the Perpendicular style; carved screens to choir and altar, and rood screen; a spire on top of the old tower.[9] The exterior of the church (apart from the Victorian broach-spire) also dates from the 15th century,[3] and is fashioned from local flint and stone covered with plaster.[10] A chapel was also constructed in the southern nave, which is the current choir vestry,[11] as well as a chapel to the north of the choir called the Champflour Chantry Chapel (of which only a stone fragment remains). The royal licence for the building of this chapel was issued on 20 October 1463:

Sir Maurice Berkeley, Sir John Parre, Hugh Crikland, perpetual vicar of Alton, and others, to found a chantry of one chaplain to celebrate daily in a chapel lately built by John Champfloure in the said parish church.[11]

16th–17th century

Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, St Lawrence's passed to the patronage of the Dean and Chapter of Winchester on 1 May 1541.[11] It appears that in this period the church was also a seat of learning; with the exception of Winchester College, the oldest record of any educational establishment in Hampshire comes from a report of 1548 to Edward VI's Chantry Commissioners, which states that there was in Alton:

a stipendiary Priest, founded by one John Chanflower, to have continuance for ever, to the intent to assist ministration in the Church of Alton and to teache children grammer.[11]

Couper writes that the church "must have been gravely despoiled at this time",[12] but gives scant evidence for this claim. Further building work occurred in the 16th century – the south door and porch, a priest's entrance to the Lady Chapel (made by the vicar Ralph Herriott; his initials may be seen on it)[12] – but it is only in the 17th century, again in Couper's words, that the church "steps into the full light of day",[13] with an instruction of Elizabeth I to the local JPs that the Poor Law provisions are being implemented, the beginning of the parish registers in 1615 and the churchwarden's accounts in 1625.[13] These continue unbroken to the present day, except for some minor gaps during the upheaval of the English Civil War.[13] The churchwarden accounts of 1625 mention that the church possesses a peal of bells, and these were rung when Charles I came to the town in 1625.[13] The church's pulpit – described as "an outstanding mid c17 piece" in Pevsner[3] – dates from this period.

Battle of Alton

St Lawrence's played a significant part in the Battle of Alton – part of the English Civil War – which took place on 13 December 1643. Alton was a Royalist town, and on 1 December 1643, a large force, commanded by the Earl of Crawford, occupied the town. Parliamentary forces, led by Sir William Waller, marched against Alton on 13 December and Crawford fled the town for Winchester, leaving behind a small force commanded by Colonel Richard Boles[14] (Godwin gives his name as "Bolle"[15]). This defensive force was beaten back through Amery Farm and the churchyard of St Lawrence's, and eventually barricaded themselves in the church itself, where, "having made scaffolds in the Church to fire out of the windows [they] fired very thick from every place."[14]

According to Tony MacLachlan:

"For the Royalists, the fighting was just a splendid gesture of defiance, meaningful, spirited and dignified, but hopeless. Two hundred men, with their backs to the wall and seeing the church behind as their only chance of survival, pulled back towards the open doorway, still fighting, and hearing throughout the cries of the dying. Pikes were snapped in the low doorway, and those within the church were already attempting to close the doors. But the pressure of the distressed outside forced the doors open again, and the last of the sanctuary seekers went inside."

— [16]

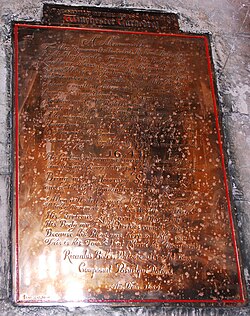

After a concerted assault, during which, according to the Parliamentarian Lieutenant Archer, "the churchyard was full of our men, laying about them stoutly with halberts, swords, and musket-stocks, while some threw hand-granadoes in at the church windows,"[15] the Parliamentarians eventually broke through the west door of the church, and Colonel Boles, who had threatened to kill any of his soldiers who asked for quarter,[17] was killed – the traditional place given for his death was on the steps of the pulpit.[14][17] (The brass to Boles states that his force in the church was "neare four score strong".)[18] Bullet holes can be seen in the church's south door, as well as in both external and internal walls and pillars. When the church was restored in the 1860s many bullets were removed from the church ceiling, and a number of soldiers who died in the fighting were dug up in the churchyard; various relics of the battle – a key, a uniform button, bullets and a pipe – are displayed in a cabinet in the church.[14] A brass memorial to Boles is on one of the arcade pillars in the church. A facsimile of a tablet at his tomb in Winchester Cathedral (and containing the same mistakes – the date of the battle, for instance, is given as 1641), it states in part:

- Alton will tell you of that famous Fight

- Which y man made & bade this world good night

- His verteous Life fear'd not Mortalyty

- His Body must, his Vertues cannot Die

- Because his Bloud was there so nobly spent

- This is his Tombe that Church his Monument.[17]

When Charles I heard of Boles's death he is said to have exclaimed, "Bring me my mourning scarf; I have lost one of my best commanders in this Kingdom."[19]

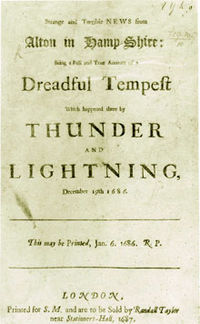

1686 thunderstorm

On 19 December 1686 a violent thunderstorm took place in Alton that damaged much of the church. According to an eye-witness account:

On Sunday when the Reverend Minister of the parish was towards the latter end of Prayer before Sermon, it grew on a sudden so exceeding dark that the People could hardly discern one another, and immediately after happened such flashes of lightning that the whole Church seemed to be in a bright flame; the surprise of the Congregation was exceeding great, especially when two Balls of Fire made their entry at the Eastern Wall, pass'd through the body of the Church, leaving behind 'em so great a Smoke, and Smell of Brimstone as is scarce able to be expresst.[20]

All of the church's windows were broken, the roof and steeple were badly damaged after being set on fire, the tower had a hole blasted through it and the weathercock, according to the same eye-witness, "was carried quite away, and the hand and Boards belonging to the Clock fell among the Congregation."[20] No one was hurt, but the vicar's eyebrows were singed.[20] The churchwarden's accounts for 1687 list many repairs having taken place in the preceding months, but the church bells rang both in 1687 when James II passed through Alton and in 1688 upon the proclamation of William and Mary.[20]

18th century

During the 18th century a large number of galleries were built in the church. Couper comments:

When the ringers rang for Queen Anne's Coronation in 1702, there was only one gallery in St. Lawrence's; when they rang for Queen Victoria's coronation the Church was filled with galleries in every conceivable place.[20]

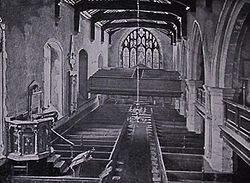

Amongst the galleries were: a singing gallery at the west end; two or three at the east end (one of these was over the high altar (pictured, right)); various galleries filling the southern nave, with staircases leading up to them, "some of which were for paying customers and some free."[21]

In 1724 work began to change the church roof from tiles to lead, work that was completed in 1758; until this point the church had a three-span roof but this work saw the roof assuming the one-span structure that is maintained to the current day.[22] In 1742 the plain window on the northern wall behind the pulpit was replaced "with a Square Crown Glass in order to give it better light, and also to alter the Sounding Board in such a manner as shall be thought most proper upon the opinion of the Revd. Mr. Smith, Vicar, and the workman."[22] According to Couper, the housekeeping records during this century became "more meticulous than ever"; records were kept of the monies received for each member of the congregation ("1/- for each person 'seated' in the Church or Churchyard, and 3/4 for a child's")[23] as well as for items such as "a pound of soft soap" (7d), "oyle" (3d) and "a chamber pott" (9d).[23]

The charitable works undertaken by the church are also meticulously detailed; this was the era in which charitable trusts were set up, and we find that John Fisher made a gift of £8 in 1741, which was "as an annual allowance for three sermons to be preached in Alton Church on the Anniversary of his death, and for a distribution of bread and money to the Poor of Alton."[24] The Poor House was established in 1740 in the Malt House on Mount Pleasant, and the church was also responsible for housing and maintaining the town fire engine; the churchwardens' records contain details of the costs involved in its "oyling".[24]

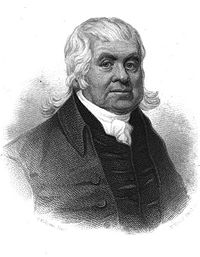

John Murray, the founder of the Universalist denomination in the United States, was born in 1741 in Alton and baptised in St Lawrence's. Murray's Life gives an account of the customs surrounding baptism at St Lawrence's:

I was hardly two years old, when I had a sister born; this sister was presented at the baptismal font, and, according to the custom in our Church, I was carried to be received, that is, all who are privately baptized, must, if they live, be publicly received in the congregation. The priest took me in his arms, and having prayed, according to the form made use of on such occasions, I articulated, with an audible voice, Amen. The congregation were astonished, and I have frequently heard my parents say, this was the first word I ever uttered, and that a long time elapsed, before I could distinctly articulate any other.[25]

19th century

Three further galleries were built in 1810 and 1824, at a cost of £200 and £150 respectively.[26] In 1817 Francis Austen, the brother of Jane Austen who lived a few miles south-west of Alton in Chawton, was appointed to a committee to "superintend and investigate the affairs of the parish",[27] possibly on account of the problems being caused at the time by the collection of tithes, which had led to the breaking of all of the windows of the vicarage.[27] In 1829 the church, apparently with "some reluctance", bought a "barrel organ", which "shall have finger keys as well as barrels".[27]

Restoration

In 1862, in the most significant decision affecting the church in the modern era, an appeal was launched by Canon Woodrooffe for the restoration of the church. The appeal read:

The population of the Parish of Alton, Hants, amounted at the recent census to 3,769. The Parish Church affords very insufficient room for the requirements of the Inhabitants, the total number of sitting being 899; and the Church Wardens have, for a considerable time past, found it impossible to meet the applications which are continually made for Pews. But the greatest want is that of suitable accommodation for the Working Classes ... A Plan and Estimate have been obtained from an experienced Architect for removing all the present galleries, adding a North Aisle and Western Gallery to the Church, and Re-pewing the whole, so as to yield increased accommodation for 200 persons, and to make the Sittings generally suitable and convenient. The cost of effecting these improvements is estimated at £2,500.[28]

A ceremony marking the completion of the renovations was held on 16 April 1868, when the Bishop of Winchester reopened the church.[29] Amongst the items that had been given to the church were a new font, a lectern (carved by Revd A. W. Deey), several new windows, and new seating for the chancel.[29] The most notable addition was an organ, paid for by public subscription (at a cost of £850[30]), and built by Messrs Speechly and Ingram. It was used until its rebuilding in 1966, and in 1898 a gas engine to power it was bought from Winchester Cathedral for £25.[29] A permanent choir was also created, under the direction of Mr H. D. Newman, the organist.[29] A number of other modifications to the church were made – a window was added to the tower and a staircase to the belfry, the west door was filled in with stone, and new pews installed – but, in Couper's words, "on the whole the restoration was carried out with restraint, and the interior of the Parish Church returned in essence very nearly to what it had been in the 15th century."[30] The church now seated 816 people, compared with the 899 it seated before the restoration.[30] To cater for the enlarged population of Alton, a new church was built (All Saints' Church) and the parish divided.[30]

Tower, steeple and clocks

In 1874, on the initiative of the Alton Church Tower and Steeple Repairing Fund, the steeple was faced with oak to replace the lead that previously covered it, and a weather vane was placed atop it; this is the steeple that we see today.[30] Over the years a number of turret clocks have been positioned on the tower; Couper states that there had been one since "at least the 17th century", based on the references in the church accounts to "the diall",[31] and it has a clock (not on display) with the date 1700 on it. The clock in use today was installed in 1890 by Messrs J. W. Benson; a Mrs Gerald Hall started its mechanism at 12 noon on Saturday 7 June 1890.[31] Sundials have also long been used in the church; one on a buttress on the church's east face is either from the 14th century or earlier.[31] The one currently in the churchyard dates from the 18th century.[31]

Stained glass

All of the stained glass in the church comes from the Victorian period; the east window (1870) was filled by Jean-Baptiste Capronnier of Brussels; the Mary window beside the pulpit (1873) is dedicated to Martha Hutchins; the window in the Lady Chapel (1884), like the Mary window, was filled by Messrs Heaton, Butler and Bayne of London.[30] The window to the north of the high altar (1899) depicts the archangels Gabriel, Michael and Raphael; it was dedicated to Henry Hall (the brewer).[30] When Hall's wife died, the mosaic to Faith and Charity, which surrounds the archangel window, was put up in 1906.[31]

20th century

Chapel of St Michael and St George

The Lady Chapel was converted into a war memorial following an initiative that began immediately after the end of World War I in 1918.[32] During the war the vicar had kept the names of soldiers who were killed on a roll of vellum parchment; at the end of the war this was transcribed onto a mural tablet with the words: To the glory of God/In memory of the men of this town/Who gave their lives in the Great War 1914–18/And in thankfulness for many who have been spared/This chapel is restored A.D. 1919.

The chapel was dedicated by the Bishop of Winchester on 28 November 1920, and in 1927 the two figures of St Michael and St George, which occupy the niches at the east end of the southern nave once filled by the statues of St Lawrence and the Virgin and Child, were donated by Miss E. H. Davenport.[7] Other additions to the chapel include: various new tablets, oak moveable pews and a grand piano.

Further changes

An appeal of 1920 raised £2,743 16. 7 for the church, the main work being done on the tower and the roof. The western gallery that was part of the 1868 renovations was taken down.[7] A new ring of eight bells was cast for the church in 1926 by Gillett & Johnston; the bells were hung for change ringing[33] and the old oak frame was replaced by one made of steel.[7] In 1932 it was discovered that the tower was cracking in many places, partly as a result of the bells' vibrations, so the bell cage was reinforced with steel and the walls around it were strengthened with reinforced concrete.[7] In 1939 the church was converted from gas to electric lighting, in memory of Dr E. J. L. Leslie, the vicar's warden from 1906 to 1936.[7]

Further work was carried out on the organ in 1993.[34]

The parish centre is St Lawrence Hall, which was built 100 m south of the church in 1970.[35]

Vicars

Church of St Lawrence from various aspects

-

From north

-

From west

-

From south-west

-

From south-east

-

From north-east

-

Clock and tower

Footnotes

- ^ Curtis (1896), p. 50

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Couper (1970), p. 9

- ^ a b c d e Pevsner and Lloyd (2002), p. 76

- ^ Curtis (1896), p. 54

- ^ a b Couper (1970), p. 10

- ^ Couper (1970), p. 11

- ^ a b c d e f Couper (1970), p. 42

- ^ a b c Couper (1970), p. 12

- ^ Couper (1970), pp. 12–13

- ^ Curtis (1896), p. 52

- ^ a b c d Couper (1970), p. 13

- ^ a b Couper (1970), p. 15

- ^ a b c d Couper (1970), p. 16

- ^ a b c d Couper (1970), pp. 17–18

- ^ a b Godwin (1973), p. 145

- ^ MacLachlan (2000), pp. 182–4

- ^ a b c MacLachlan (2000), p. 184

- ^ Godwin (1973) p. 146

- ^ Hepper (2005), p.2

- ^ a b c d e Couper (1970), p. 21

- ^ Couper (1970), p. 21–3

- ^ a b Couper (1970), p. 23

- ^ a b Couper (1970), p. 24

- ^ a b Couper (1970), p. 25

- ^ Murray (1831), p. 10

- ^ Couper (1970), pp. 28--9

- ^ a b c Couper (1970), p. 29

- ^ Couper (1970), pp. 31--3

- ^ a b c d Couper (1970), p. 33

- ^ a b c d e f g Couper (1970), p. 35

- ^ a b c d e Couper (1970), p. 37

- ^ Couper (1970), p. 41

- ^ "Alton—S Lawrence". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council for Church Bell Ringers. 7 July 2007. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Church of St Lawrence organ, www.stlawrencealton.org. Retrieved 6 March 2010

- ^ Church of St Lawrence parish centre, www.stlawrencealton.org. Retrieved 6 March 2010

- ^ Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP 40/555;http://aalt.law.uh.edu/H4/CP40no555/bCP40no555dorses/IMG_0250.htm; first entry; "John Neuport , cl'cus. vicar ecclie. de Aulton" as the complainant, with "Sutht" in the margin

- ^ National Archives; PROB 11; Will of Johannes Mathew, of Alton, Hants; proved 20 Nov 1501; lines 30 31 " Et superv... huius testamenti mea ordino Magister Joh' Shavyngton vicarium de Alton"

- ^ Will of Lawrence Geale, proved 1629; Hampshire Record Office 1629A/32 "to Wm. Tindall for to preach at my burial 20/-"

- ^ Will of William Tyndall, cleric, vicar of Alton. Hampshire Record Office; 1646B/26

- ^ Will of Mary Tyndall, of Alton, widow; proved 1677; Hampshire Record Office; 1677A/094. From reading these wills it is evident that Mary, the widow of Lawrence Geale, married William Tyndall

References

- Couper, D. L. (1970). The Story of the Parish Church of St. Lawrence, Alton. Gloucester: British Publishing Company Limited. ISBN 0-7140-0728-5.

- Curtis, William (1896). A Short History and Description of the Town of Alton: In the County of Southampton. Winchester: Warren and Son. ISBN 1-104-00986-2.

- Godwin, George Nelson (1973). The Civil War in Hampshire (1642-45) and the Story of Basing House. Southampton: H. M. Gilbert and Son. ISBN 0-9501347-2-4.

- Hepper, Edward; Hepper, Judith (2005). The Battle of Alton, 1643 and St Lawrence Church (pamphlet). Alton: The Parish of St Lawrence.

- MacLachlan, Tony (2000). The Civil War in Hampshire. Landford, Salisbury: Rowanvale Books. ISBN 0-9530785-3-1.

- Murray, John (1831). Records of the Life of the Rev. John Murray. Boston: Marsh Capen and Lyle.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Lloyd, David (2002). The Buildings of England: Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09606-2.