Climate change in Australia

This article's lead section may be too long. (November 2019) |

This article may be in need of reorganization to comply with Wikipedia's layout guidelines. (November 2019) |

Climate change in Australia has been a critical issue since the beginning of the 21st century.[1] In 2013, the CSIRO released a report stating that Australia is becoming hotter, and that it will experience more extreme heat and longer fire seasons because of climate change.[2] In 2014, the Bureau of Meteorology released a report on the state of Australia's climate that highlighted several key points, including the significant increase in Australia's temperatures (particularly night-time temperatures) and the increasing frequency of bush fires, droughts and floods, which have all been linked to climate change.[3]

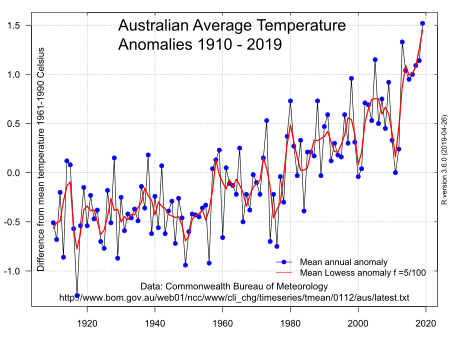

Since the beginning of the 20th century Australia has experienced an increase of nearly 1 °C in average annual temperatures, with warming occurring at twice the rate over the past 50 years than in the previous 50 years.[4] Recent climate events such as extremely high temperatures and widespread drought have focused government and public attention on the impacts of climate change in Australia.[5] Rainfall in southwestern Australia has decreased by 10–20% since the 1970s, while southeastern Australia has also experienced a moderate decline since the 1990s.[6] Rainfall patterns are expected to be problematic, as rain has become heavier and infrequent, as well as more common in summer rather than in winter, with little or no uptrend in rainfall in the Western Plateau and the Central Lowlands of Australia.[7] Water sources in the southeastern areas of Australia have depleted due to increasing population in urban areas (rising demand) coupled with climate change factors such as persistent prolonged drought (diminishing supply). At the same time, greenhouse gas emissions by Australia continue to be the highest per capita greenhouse gas emissions in the OECD.[8] Temperatures in Australia have also risen dramatically since 1910 and nights have become warmer.[9][failed verification]

A carbon tax was introduced in 2011 by the Gillard government in an effort to reduce the impact of climate change and despite some criticism, it successfully reduced Australia's carbon dioxide emissions, with coal generation down 11% since 2008–09.[10] The subsequent Australian Government, elected in 2013 under then Prime Minister Tony Abbott was criticised for being "in complete denial about climate change".[11] Abbott became known for his anti-climate change positions as was evident in a number of policies adopted by his administration. In a global warming meeting held in the United Kingdom, he reportedly said that proponents of climate change are alarmists, underscoring a need for "evidence-based" policymaking.[12] The Abbott government repealed the carbon tax on 17 July 2014 in a heavily criticised move.[13] The renewable energy target (RET), launched in 2001, was also modified.[14] However, under the government of Malcolm Turnbull, Australia attended the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference and adopted the Paris Agreement, which includes a review of emission reduction targets every 5 years from 2020.[15]

The federal government and all state governments (New South Wales,[16] Victoria,[17] Queensland,[18] South Australia,[19] Western Australia,[20] Tasmania,[21] Northern Territory[22] and the Australian Capital Territory[23]) have explicitly recognised that climate change is being caused by greenhouse gas emissions, in conformity with the scientific opinion on climate change. Sectors of the population have campaigned against new coal mines and coal-fired power stations, reflecting concerns about the effects of global warming on Australia.[24][25][26] The Garnaut Climate Change Review predicted that a net benefit to Australia may be derived by stabilising greenhouse gases in the atmosphere at 450 ppm CO2 eq.[27]

The carbon emissions in Australia have been rising every year since the Coalition Government abolished the carbon tax.[28][clarification needed]

Predictions measuring the effects of global warming on Australia assert that global warming will negatively impact the continent's environment, economy, and communities. Australia is vulnerable to the effects of global warming projected for the next 50 to 100 years because of its extensive arid and semi-arid areas, an already warm climate, high annual rainfall variability, and existing pressures on water supply. The continent's high fire risk increases this susceptibility to change in temperature and climate. Additionally, Australia's population is highly concentrated in coastal areas, and its important tourism industry depends on the health of the Great Barrier Reef and other fragile ecosystems. The impacts of climate change in Australia will be complex and to some degree uncertain, but increased foresight may enable the country to safeguard its future through planned mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation may reduce the ultimate extent of climate change and its impacts, but requires global solutions and cooperation, while adaptation can be performed at national and local levels.[29]

Pre-instrumental climate change

Paleoclimatic records indicate that during glacial maxima Australia was extremely arid,[30] with plant pollen fossils showing deserts extending as far as northern Tasmania and a vast area of less than 12% vegetation cover over all of South Australia and adjacent regions of other states. Forest cover was largely limited to sheltered areas of the east coast and the extreme southwest of Western Australia.

During these glacial maxima the climate was also much colder and windier than today.[31] Minimum temperatures in winter in the centre of the continent were as much as 9 °C (16 °F) lower than they are today. Hydrological evidence for dryness during glacial maxima can also be seen at major lakes in Victoria's Western District, which dried up between around 20,000 and 15,000 years ago and re-filled from around 12,000 years ago.[32]

During the early Holocene, there is evidence from Lake Frome in South Australia and Lake Woods near Tennant Creek that the climate between 8,000 and 9,500 years ago and again from 7,000 to 4,200 years ago was considerably wetter than over the period of instrumental recording since about 1885.[33] The research that gave these records also suggested that the rainfall flooding Frome was certainly summer-dominant rainfall because of pollen counts from grass species. Other sources[34] suggest that the Southern Oscillation may have been weaker during the early Holocene and rainfall over northern Australia less variable as well as higher. The onset of modern conditions with periodic wet season failure is dated at around 4,000 years before the present.

In southern Victoria, there is evidence for generally wet conditions except for a much drier spell between about 3,000 and 2,100 years before the present,[35] when it is believed Lake Corangamite fell to levels well below those observed between European settlement and the 1990s. After this dry period, Western District lakes returned to their previous levels fairly quickly and by 1800 they were at their highest levels in the forty thousand years of record available.

Elsewhere, data for most of the Holocene are deficient, largely because methods used elsewhere to determine past climates (like tree-ring data) cannot be used in Australia owing to the character of its soils and climate. Recently, however, coral cores have been used to examine rainfall over those areas of Queensland draining into the Great Barrier Reef.[36] The results do not provide conclusive evidence of man-made climate change, but do suggest the following:

- There has been a marked increase in the frequency of very wet years in Queensland since the end of the Little Ice Age, a theory supported by there being no evidence for any large Lake Eyre filling during the LIA.

- The dry era of the 1920s and 1930s may well have been the driest period in Australia over the past four centuries.

A similar study, not yet published, is planned for coral reefs in Western Australia.

Records exist of floods in a number of rivers, such as the Hawkesbury, from the time of first settlement. These suggest that, for the period beginning with the first European settlement, the first thirty-five years or so were wet and were followed by a much drier period up to the mid-1860s,[37] when usable instrumental records started.

Instrumental climate records

Development of an instrumental network

Although rain gauges were installed privately by some of the earliest settlers, the first instrumental climate records in Australia were not compiled until 1840 at Port Macquarie. Rain gauges were gradually installed at other major centres across the continent, with the present gauges in Melbourne and Sydney dating from 1858 and 1859 respectively.

In eastern Australia, where the continent's first large-scale agriculture began, a large number of rain gauges were installed during the 1860s and by 1875 a comprehensive network had been developed in the "settled" areas of that state.[38] With the spread of the pastoral industry to the north of the continent during this period, rain gauges were established extensively in newly settled areas, reaching Darwin by 1869, Alice Springs by 1874, and the Kimberley, Channel Country and Gulf Savannah by 1880.

By 1885,[39] most of Australia had a network of rainfall reporting stations adequate to give a good picture of climatic variability over the continent. The exceptions were remote areas of western Tasmania, the extreme southwest of Western Australia, Cape York Peninsula,[40] the northern Kimberley and the deserts of northwestern South Australia and southeastern Western Australia. In these areas good-quality climatic data were not available for quite some time after that.

Temperature measurements, although made at major population centres from days of the earliest rain gauges, were generally not established when rain gauges spread to more remote locations during the 1870s and 1880s. Although they gradually caught up in number with rain gauges, many places which have had rainfall data for over 125 years have only a few decades of temperature records.

Climate history based on instrumental records

Australia's instrumental record from 1885 to the present shows the following broad picture:

Conditions from 1885 to 1898 were generally fairly wet, though less so than in the period since 1968. The only noticeably dry years in this era were 1888 and 1897. Although some coral core data[41] suggest that 1887 and 1890 were, with 1974, the wettest years across the continent since settlement, rainfall data for Alice Springs, then the only major station covering the interior of the Northern Territory and Western Australia, strongly suggest that 1887 and 1890 were overall not as wet as 1974 or even 2000.[42] In New South Wales and Queensland, however, the years 1886–1887 and 1889–1894 were indeed exceptionally wet. The heavy rainfall over this period has been linked with a major expansion of the sheep population[43] and February 1893 saw the disastrous 1893 Brisbane flood.

A drying of the climate took place from 1899 to 1921, though with some interruptions from wet El Niño years, especially between 1915 and early 1918 and in 1920–1921, when the wheat belt of the southern interior was drenched by its heaviest winter rains on record. Two major El Niño events in 1902 and 1905 produced the two driest years across the whole continent, whilst 1919 was similarly dry in the eastern States apart from the Gippsland.

The period from 1922 to 1938 was exceptionally dry, with only 1930 having Australia-wide rainfall above the long-term mean and the Australia-wide average rainfall for these seventeen years being 15 to 20 per cent below that for other periods since 1885. This dry period is attributed in some sources to a weakening of the Southern Oscillation[44] and in others to reduced sea surface temperatures.[45] Temperatures in these three periods were generally cooler than they are currently, with 1925 having the coolest minima of any year since 1910. However, the dry years of the 1920s and 1930s were also often quite warm, with 1928 and 1938 having particularly high maxima.

The period from 1939 to 1967 began with an increase in rainfall: 1939, 1941 and 1942 were the first close-together group of relatively wet years since 1921. From 1943 to 1946, generally dry conditions returned, and the two decades from 1947 saw fluctuating rainfall. 1950, 1955 and 1956 were exceptionally wet except 1950 and 1956 over arid and wheatbelt regions of Western Australia. 1950 saw extraordinary rains in central New South Wales and most of Queensland: Dubbo's 1950 rainfall of 1,329 mm (52 inches) can be estimated to have a return period of between 350 and 400 years, whilst Lake Eyre filled for the first time in thirty years. In contrast, 1951, 1961 and 1965 were very dry, with complete monsoon failure in 1951/1952 and extreme drought in the interior during 1961 and 1965. Temperatures over this period initially fell to their lowest levels of the 20th century, with 1949 and 1956 being particularly cool, but then began a rising trend that has continued with few interruptions to the present.

Since 1968, Australia's rainfall has been 15 per cent higher than between 1885 and 1967. The wettest periods have been from 1973 to 1975 and 1998 to 2001, which comprise seven of the thirteen wettest years over the continent since 1885. Overnight minimum temperatures, especially in winter, have been markedly higher than before the 1960s, with 1973, 1980, 1988, 1991, 1998 and 2005 outstanding in this respect. There has been a marked and beneficial decrease in the frequency of frost across Australia.[46]

According to the Bureau of Meteorology, Australia's annual mean temperature for 2009 was 0.90 °C above the 1961–90 average, making it the nation's second-warmest year since high-quality records began in 1910.[47]

Record heat in 2010-2017

According to Australian Climate Council in 2017 Australia had its warmest winter on record, in terms of average maximum temperatures, reaching nearly 2 °C above average.[48]

Summer 2013–14 was warmer than average for the entirety of Australia.[49] Both Victoria and South Australia saw record-breaking temperatures. Adelaide recorded a total of 13 days reaching 40 °C or more, 11 of which reached 42 °C or more, as well as its fifth-hottest day on record—45.1 °C on January 14. The number of days over 40 °C beat the previous record of summer 1897–1898, when 11 days above 40 °C were recorded. Melbourne recorded six days over 40 °C, while nighttime temperatures were much warmer than usual, with some nights failing to drop below 30 °C.[50]

Overall, the summer of 2013–2014 was the third-hottest on record for Victoria, fifth-warmest on record for New South Wales, and sixth-warmest on record for South Australia.[49] 2015 was Australia's fifth-hottest year on record, continuing the trend of record-breaking high temperatures across the country.[51]

Local variations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2008) |

This article possibly contains original research. (November 2008) |

Within Australia, patterns of precipitation show regional variation. Because of the general spatial coherence of rainfall over most of Australia, these variations have tended to affect small areas, but because these are generally the most populated parts of the continent, they are still of considerable importance.

In the South-West Land Division, rainfall during the May to August rainy season has declined by 20 per cent since 1968, after being at its highest from 1915 to 1947.[52] Floods that were once common have virtually disappeared. Aided by increased winter temperatures and evaporation, run-off has declined over the past forty years by as much as sixty per cent.[citation needed]

- In southern Victoria, rainfall since 1997 has declined by as much as 30 per cent, with Melbourne having not once exceeded its 1885 to 1996 average since 1997.[citation needed]

- In contrast, the 1950s in southern Victoria were consistently wet, with Western District lakes returning during the decade to levels seen before the 1850s and Corangamite almost overflowing, as it is believed to have done during the Little Ice Age.[citation needed]

- The eastern part of Tasmania has also seen a major decline in rainfall since the middle 1970s. In Hobart, the annual rainfall has declined by about one-sixth since that time, and not one of the nineteen wettest years since 1882 has occurred since 1976.[citation needed]

- In Gippsland, the coastal areas of New South Wales, and southern Queensland, the driest period since 1885 was not from 1922 to 1938, but approximately from 1901 to 1910, when the average annual rainfall at Sydney was 20 per cent below its long-term mean. There was a slight increase in rainfall from 1916 to 1934 and then a decline to 1901–1910 levels from 1936 to 1948, before a return to the pre-1900 "flood-dominated" climate regime occurred in 1949.[citation needed]

- In northwestern Australia, rainfall was moderate from 1885 to about 1925, then declined from the late 1920s to the late 1960s (with very dry conditions during the 1950s), followed by rapid increases since then. In Darwin, six of the seven wettest wet seasons have occurred since 1995, and the major droughts that once affected the region frequently have virtually disappeared since 1971.[citation needed]

Effects of climate change on Australia

According to the CSIRO and Garnaut Climate Change Review, climate change is expected to have numerous adverse effects on many species, regions, activities and much infrastructure and areas of the economy and public health in Australia. The Stern Report and Garnaut Review on balance expect these to outweigh the costs of mitigation. [53]

Sustained climate change could have drastic effects on the ecosystems of Australia. For example, rising ocean temperatures and continual erosion of the coasts from higher water levels will cause further bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef. Beyond that, Australia's climate will become even harsher, with more powerful tropical cyclones and longer droughts.[54]

The impacts of climate change will vary significantly across Australia. The Australian Government appointed Climate Commission have prepared summary reports on the likely impacts of climate change for regions across Australia, including: Queensland, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania.[55]

Climate Commission reports

According to the Climate Commission (now Australian Climate Council) report in 2013, the extreme heatwaves, flooding and bushfires striking Australia have been intensified by climate change and will get worse in future in terms of their impacts on people, property, communities and the environment.[56] The summer of 2012/2013 included the hottest summer, hottest month and hottest day on record. The cost of the 2009 bushfires in Victoria was estimated at A$4.4bn (£3bn) and the Queensland floods of 2010/2011 cost over A$5bn.[57][58][59]

By 2014, another report revealed that, due to the change in climatic patterns, the heat waves were found to be increasingly more frequent and severe, with an earlier start to the season and longer duration.[56] The report also cited that the current heat wave levels in Australia were not anticipated to occur until 2030. All these underscored the kind of threat that Australia faces. As a developed country, its coping strategies are more sophisticated but it is the rate of change that will pose the bigger risks.[60]

Sea level rise

The Australian Government released a report on the impacts of climate change on coastal areas of Australia, finding that up to 247,600 houses are at risk from flooding from a sea-level rise of 1.1 metres. There were 39,000 buildings located within 110 metres of 'soft' erodible shorelines, at risk from accelerated erosion due to sea -level rise.[61] Adaptive responses to this specific climate change threat are often incorporated in the coastal planning policies and recommendations at the state level.[62] For instance, the Western Australia State Coastal Planning Policy established a sea-level rise benchmark for initiatives that address the problem over a 100-year period.[62]

Economy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2008) |

In 2008 the Treasurer and the Minister for Climate Change and Water released a report that concluded the economy will grow with an emissions trading scheme in place.[63]

A report released in October 2009 by the Standing Committee on Climate Change, Water, Environment and the Arts, studying the effects of a 1m sea level rise, quite possible within the next 30–60 years, concluded that around 700,000 properties around Australia, including 80,000 buildings, would be inundated, the collective value of these properties is estimated at $155 billion.[64]

Water

Bureau of Meteorology records since the 1860s show that a ‘severe’ drought has occurred in Australia, on average, once every 18 years.[65]

In June 2008 it became known that an expert panel had warned of long term, maybe irreversible, severe ecological damage for the whole Murray-Darling basin if it did not receive sufficient water by October of that year.[66] Water restrictions were in place in many regions and cities of Australia in response to chronic shortages resulting from the 2008 drought.[67] In 2004 paleontologist Tim Flannery predicted that unless it made drastic changes the city of Perth, Western Australia, could become the world's first ghost metropolis – an abandoned city with no more water to sustain its population.[68] However, with increased rainfall in recent years, the water situation has improved.[citation needed]

In 2019 the drought and water resources minister of Australia David Littleproud, said, that he "totally accepts" the link between climate change and drought in Australia because he "live it". He says that the drought in Australia is already 8 years long. He called for a reduction in Greenhouse gas emission and massive installation of renewable energy. Former leader of the nationalists Barnaby Joyce said that if the drought became more fierce and dams will not be built, the coalition risk "political annihilation"[69]

Adaptation

Action on climate change

Climate change featured strongly in the November 2007 Australian federal election in which John Howard was replaced by Kevin Rudd as Prime Minister. The first official act of the new Australian Government was to ratify the Kyoto Protocol.

Government action

National

This article needs to be updated. (August 2019) |

In 1998 the Australian Government, under Prime Minister John Howard, established the Australian Greenhouse Office, which was then the world's first government agency dedicated to cutting greenhouse gas emissions.[70] the new Department of Climate Change under Minister Penny Wong was coordinating and leading climate policy in the Australian Government and aimed to have a national emissions trading scheme operating by 2010. However, on 27 April 2010, the Prime Minister Kevin Rudd announced that the Government has decided to delay the implementation of the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (CPRS) until the end of the first commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol (ending in 2012).[71] The government cited the lack of bipartisan support for the CPRS and slow international progress on climate action as the reasons for the decision.[72]

The delay of the implementation of the CPRS was strongly criticised by the Federal Opposition[73] and by community and grassroots action groups such as GetUp.[74]

The new government has committed to reducing Australia's greenhouse gas emissions by 60% by 2050, based on year 2000 levels but is awaiting a report from Professor Ross Garnaut, the Garnaut Climate Change Review, in mid-2008 before setting interim emission reduction targets for 2020. [needs update]

Climate change is on the agenda for most environmental and social justice non-government organisations (NGOs) in Australia. There has also been significant action at a State Government level, although the Federal government was slow to act under the former prime minister, John Howard[citation needed].

To reduce Australia's carbon emissions, the government of Julia Gillard introduced a carbon tax on 1 July 2012. It requires large businesses, defined as those emitting over 25,000 tons of [75]carbon dioxide equivalent annually, to purchase emissions permits.

Australia attended the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference and adopted the Paris Agreement. The agreement includes a review of emission reduction targets every five years from 2020.[15]

Australia's Clean Energy Target (CET) came under threat in October 2017 from former Prime Minister Tony Abbott. This could lead to the Labor Party withdrawing support from the Turnbull government's new energy policy.[76][77]

Climate policy continues to be controversial. Following the repeal of the carbon price in the last parliament, the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) is now Australia's main mechanism to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. However, two-thirds of the ERF's allocated $2.5 billion funding has now been spent. The ERF, and other policies, will need further funding to achieve our climate targets.[78]

State

Victoria

The state of Victoria, in particular, has been proactive in pursuing reductions in GHG through a range of initiatives. In 1989 it produced the first state climate change strategy, "The Greenhouse Challenge". Other states have also taken a more proactive stance than the federal government. One such initiative undertaken by the Victorian Government is the 2002 Greenhouse Challenge for Energy Policy package, which aims to reduce Victorian emissions through a mandated renewable energy target. Initially, it aimed to have a 10 per cent share of Victoria's energy consumption being produced by renewable technologies by 2010, with 1000 MW of wind power under construction by 2006. The government legislated to ensure that by 2016 electricity retailers in Victoria purchase 10 per cent of their energy from renewables. This was ultimately overtaken by the national Renewable Energy Target (RET). By providing a market incentive for the development of renewables, the government helps foster the development of the renewable energy sector. A Green Paper and White Paper on Climate Change was produced in 2010, including funding for a number of programs. A Climate Change Act was passed including targets for 50% reduction in emissions. A recent review of this Act has recommended further changes.

South Australia

Former Premier Mike Rann (2002–2011) was Australia's first Climate Change Minister and passed legislation committing South Australia to renewable energy and emissions reduction targets. Announced in March 2006, this was the first legislation passed anywhere in Australia committed to cutting emissions.[79] By the end of 2011, 26% of South Australia's electricity generation derived from wind power, edging out coal-fired power for the first time. Although only 7.2% of Australia's population live in South Australia, in 2011, it had 54% of Australia's installed wind capacity. Following the introduction of solar feed-in tariff legislation South Australia also had the highest per-capita take up of household rooftop photo-voltaic installations in Australia. In an educative program, the Rann government invested in installing rooftop solar arrays on the major public buildings including the Parliament, Museum, Adelaide Airport, Adelaide Showgrounds pavilion and public schools. About 31% of South Australia's total power is derived from renewables. In the five years to the end of 2011, South Australia experienced a 15% drop in emissions, despite strong employment and economic growth during this period.[80]

In 2010, the Solar Art Prize was created by Pip Fletcher, and has run annually since, inviting artists from South Australia to reflect subjects of climate change and environmentalism in their work. Some winning artists receive renewable energy service prizes which can be redeemed as solar panels, solar hot water or battery storage systems.

Western Australia

On 6 May 2007, the Premier of Western Australia, Alan Carpenter announced the formation of a new Climate Change Office responsible to a Minister, with a plan that included:[81]

- a target to reduce emissions by at least 60% below 2000 levels by 2050

- a $36.5 million Low Emission Energy Development Fund

- a target to increase renewable energy generation on the South West Interconnected System to 15% by 2020 and 20% by 2025

- a clean energy target of 50% by 2010 and 60% by 2020

- State Government purchase of 20% renewable energy by 2010

- a mandatory energy efficiency program that will require large and medium energy users to invest in cost effective energy efficiency measures

- tripling the successful solar schools program so that over 350 schools will be using renewable energy by 2010

- a new $1.5 million Household Sustainability Audit and Education program that will provide practical information to households about how they can reduce greenhouse gas emissions

- investing 8.625 million to help businesses and communities adapt to the impacts of climate change

- the development of new climate change legislation

- a commitment to establishment of a national emissions trading scheme

This plan has been criticised by Greens MP Paul Llewellyn who stated that short-term programmatic targets rather than aspirational targets to greenhouse gas emissions were needed, and that renewable energy growth in the state was still being driven entirely by federal government policy and incentives, not by measures being made by the state government.

Youth Climate Movement

Australian Student Environment Network

Australian Student Environment Network (ASEN) is a non-profit, grassroots network of student activists from universities, TAFEs and secondary schools across Australia. The network aims to create a generation of change-agents actively working to achieve environmental and social justice within the Australian and world context. The network has a strong focus on equipping young people with organising and facilitation skills and provides first-hand campaigning experience in environmental advocacy and grassroots organising. Annually, the ASEN summer training camp brings together students for one week of facilitated skill sharing, workshopping, campaign planning and strategising.

ASEN has multiple campaign foci including climate change, coal mining, green jobs, campus sustainability (energy/emissions & recycled paper), nuclear power, Gold and Uranium mining and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. In addition, the network builds and lives-out alternative ideas and lifestyles through community projects such as co-operatives (food, housing and transport), on-campus permaculture gardens and by investing in community supported agriculture.

Campaigns and events

Youth

- Adopt a Politician

The AYCC supports numerous projects by harnessing the knowledge, skills and experience of its coalition member groups. In August 2007, the AYCC launched their federal election campaign "Adopt a Politician" providing young voters and non-voters a platform on which to engage with their local community on the issue and pressure their federal candidates to save their future by committing to better policies.

- Switched On

In October 2007, the AYCC and ASEN organised the largest gathering of young climate activists from around the country at the conference "Switched On" in the Blue Mountains west of Sydney. The conferenced aimed to facilitate critical thinking on climate change and its solutions, share knowledge and skills for organising around climate change and provide support and networking opportunities for the growing youth climate movement in Australia.

- Kyoto

In November 2007, youth delegates from the AYCC attended the Kyoto negotiations in Bali where they collaborated with other national youth networks and young climate activists from around the world.

- Community awareness

SYCAN-the Sydney Youth Climate Action Network was founded at OzGreen's Youth Leading Australia Congress in 2009. SYCAN is working in local communities to reduce emissions through education and practical solutions. SYCAN is a non-profit, non-partisan group of youth volunteers. SYCAN as of January 2011 currently has two branches (Northern Beaches and Inner-West areas).

Non-youth

- Walk Against Warming: annual community event supported by several NGOs and Australian Conservation Councils. Drew 40,000 in Sydney in November 2006 and 2007, 2008, December 2009 and August 2010. 40,000 attended the 2009 Melbourne walk.[82]

- Sustainability Convergence – a joint project based in Melbourne, Australia that involves a range of individuals and community groups from cross movements and sectors aiming to harness the momentum for action on climate change. The Sustainable Living Foundation provides the basic platform of the event and works with a range of groups to co-host the activities.

- The Rainforest Information Centre plans a road show of Eastern states in the first half of 2007. The workshops will comprise a brief summary of the problem and forty-minute presentation on despair and empowerment before encouraging participants to consider how to get active at a neighbourhood or community level. The intention is to establish new climate action groups and, where they exist already, to provide support, direction and connections.[83]

- The Gaia Foundation in Western Australia has been running a series of "Climate Change: Be the Change" workshops around Perth, aimed at getting individuals to undertake personal projects to limit their greenhouse gas emissions.

- GetUp! Organised online action around nine key campaigns, including climate action. Promoting five policy asks.

- Say Yes Australia campaign including Say Yes demonstrations of 5 June 2011, in which 45,000 people demonstrated in every major city nationwide in support of a price on carbon pollution.[84]

Community organising

In the Hunter Valley, alliances are being developed between unionists, environmentalists and other stakeholders. The Anvil Hill Alliance includes community and environment groups in NSW opposed to the expansion of coal mines in his high conservation value region. Their ‘statement’ has been endorsed by 28 groups.

Community engagement

Initiatives

- WWF recruited companies to participate in Australia's first Earth Hour on 31 March 2007. Participating companies turned off their lights for one hour from 7.30 pm. Cities across Europe turned off lights on public buildings including the Eiffel Tower and Colosseum during January 2007 to mark the release of an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report. Householders were also encouraged to switch off electrical appliances.

- Another WWF initiative called Climate Witness recruits individuals who can share their stories of climate change impacts and their efforts to adapt to changes.[85]

- With support from the Uniting Church and Catholic Earthcare, ACF and the National Council of Churches Australia have produced a brochure, Changing Climate, Changing Creation, which is being distributed to churches across the country.[86] The brochure encourages Australian Christians to: write to or visit their federal MP and ask what they are doing to address the threat of climate change; find out more about reducing energy and water usage and waste at home; and take action on climate change within churches and small groups.

- Ipswich Green was formed by an automotive dealer to provide like minded businesses a way of engaging the community regarding carbon emissions.

Literature Janette Hartz-Karp writes that "to deal with the complexity of climate change and oil dependency, we need a radical rethink of how to engage citizens in meaningful, influential dialogue" Deliberative democracy presents a wide range of strategies to involve communities in these important decisions.

Legal action

- Groups including Rising Tide and Queensland Conservation have initiated legal challenges to coal mines under the Commonwealth EPBC legislation. In late 2006, Queensland Conservation lodged an objection to the greenhouse gas emissions from a large coal mine expansion proposed by Xstrata Coal Queensland Pty Ltd. QC's action aimed to have the true costs of the greenhouse gas emissions from coal mining recognised. The Newlands Coal Mine Expansion will produce 28.5 million tonnes of coal over its fifteen years of operation. The mining, transport and use of this coal will emit 84 million tonnes of C02 into the atmosphere. Queensland Conservation aims to have reasonable and practical measures imposed on new mines to avoid, reduce or offset the emissions from the mining, transport and use of their coal. The Land and Resources Tribunal ruled against the case.[87]

- Peter Gray's win in the NSW Planning and Environment Court pushing the state government to consider climate change impacts in its assessment of new developments – in particular in relation to its failure to do so with Centennial Coal's proposed Anvil Hill mine.

Coalitions and alliances

- The Climate Action Network of Australia (part of Climate Action Network) coordinate communication and collaboration between 38 Australian NGOs campaigning around climate change.

- ClimateMovement.org.au is an initiative of the Nature Conservation Council. The web site includes is a hub for Climate Action Groups around Australia to connect with each other, access resources, share success stories and collaborate. It is structured around a collective blog for Climate Action Groups as well as a directory and mapping of all the community climate groups in Australia, a community events calendar and a resources section. The project encourages people to start and register new climate action groups.

- Friends of the Earth's Climate Justice campaign and work with Pacific Island and faith-based communities.

- The Six Degrees campaign is building collaborations with coal affected communities across Queensland, particularly in agricultural areas that are threatened by new coal mines and other extractive activities. The collective has also organised a number of community-led direct actions to highlight Queensland's dangerous dependence on the coal industry, including the disruption of the Tarong Coal-fired power station which supplies electricity to the Brisbane metropolis

Protests

- Rising Tide, a Newcastle-based crew, have organised actions to build pressure for a shift from coal dependence. In February 2007, more than 100 small and medium craft, including swimmers and people on surfboards, gathered in the harbour as well as on its shores as part of the peaceful demonstration. No-one was arrested even though the group attempted to surround a large freight ship as it entered the port.[88]

- In 2005, Greenpeace activists chained themselves to a loader in a Gippsland power station's coal pit.

- Young people from the Australian Student Environment Network (ASEN) shut down two coal-fired power stations in October 2007.[citation needed]

Policy advocacy

- WWF Australia's 'Clean Energy Future for Australia' outlines a range of policy recommendations for meeting electricity needs sustainably.[89]

- TEAR Australia has joined with other aid and development organisations on the Climate Change and Development NGO Roundtable.[90]

Controversies

Misleading the media on climate change emissions

The Coalition Government repeated claimed in 2019 that it turned around Australia's greenhouse gas emissions that it inherited from the Labor Government. Scott Morrison, Angus Taylor and other senior Coalition figures repeated this claim. The Coalition actually inherited a strong position from the Labor Government which had enacted the carbon tax.[91]

Proposal to outlaw climate boycotts

On 1 November 2019, Scott Morrison outlined in a speech of mining delegates at the Queensland Resources Council that he planned to legislate to outlaw climate boycotts.

Responsibility

According to the polluter pays principle, the polluter has ecological and financial responsibility for the climate change consequences. The climate change is caused cumulatively and today's emissions will have effect for decades forward.

Cumulative CO2 emissions, 1850–2007, per current inhabitant (tonnes CO2) : 1) Luxembourg 1,429 2) UK 1,127 3) US 1,126 4) Belgium 1,026 5) Czech Republic 1,006 6) Germany 987 7) Estonia 877 8) Canada 779 9) Kazakhstan 682 10) Russia 666 11) Denmark 653 12) Bahrain 631 13) Kuwait 629 15) Australia 622 tonnes CO2 16) Poland 594 17) Qatar 584 18) Trinidad & Tobago 582 19) SSlovakia 579 and 20) Netherlands 576[92]

In footprint per person in the top were by PNAS 2011: 1. Singapore 2. Luxembourg 3. Belgium 4. the US 5. Canada 6. Ireland 7. Estonia 8. Malta 9. Finland 10. Norway 11. Switzerland 12. Australia 13. Hong Kong 14. Netherlands and 15. Taiwan.[92]

Climate

Analysis of future emissions trajectories indicates that, left unchecked, human emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) will increase several fold during the 21st century. Consequently, Australia's annual average temperatures are projected to increase 0.4–2.0 °C above 1990 levels by the year 2030, and 1–6 °C by 2070. Average precipitation in southwest and southeast Australia is projected to decline during this time period, while regions such as the northwest may experience increases in rainfall. Meanwhile, Australia's coastlines will experience erosion and inundation from an estimated 8–88 cm increase in global sea level. Such changes in climate will have diverse implications for Australia's environment, economy, and public health.[93]

A 2007 technical report on climate change in Australia jointly published by Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) and the Bureau of Meteorology provided climate change projections accounting for a number of variables, including temperature, rainfall, and others. The report provided assessments of observed Australian climate changes and causes, and projections for 2030 and 2070, under a range of emissions scenarios.[94]

The Government of Australia acknowledges the impacts of changing climatic conditions, and its Department of Climate Change and Energy Efficiency has established the Australian Climate Change Science Program (ACCSP), which aims to understand the causes, nature, timing, and consequences of climate change so as to inform the Australian response. The ACCSP will dedicate $14.4 million per year towards climate change research and has already made substantial progress with a recent publication, Australian Climate Change Research: Perspectives on Successes, Challenges, and Future Directions.

Bush fires

Firefighting officials are concerned that the effects climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of bushfires under even a "low global warming" scenario.[95] A 2006 report, prepared by CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Bushfire CRC, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology, identified South Eastern Australia as one of the 3 most fire-prone areas in the world,[96] and concluded that an increase in fire-weather risk is likely at most sites over the next several decades, including the average number of days when the McArthur Forest Fire Danger Index rating is very high or extreme. It also found that the combined frequencies of days with very high and extreme FFDI ratings are likely to increase 4–25% by 2020 and 15–70% by 2050, and that the increase in fire-weather risk is generally largest inland.[97]

In 2009, the Black Saturday bushfires erupted after a period of record hot weather resulting in the loss of 173 lives [98] and the destruction of 1830 homes, and the newly found homelessness of over 7,000 people.[99]

Australian Greens leader Bob Brown said that the fires were "a sobering reminder of the need for this nation and the whole world to act and put at a priority the need to tackle climate change".[100] The Black Saturday Royal Commission recommended that "the amount of fuel-reduction burning done on public land each year should be more than doubled".[98]

In 2018, the fire season in Australia began in the winter. August 2018 is hotter and windier than the average. Those meteorologic conditions led to a drought in New South Wales. The Government of the state already give more than $1 billion to help the farmers. The hotter and drier climate led to more fires. The fire seasons in Australia are lengthening and fire events became more frequent in the latest 30 years. These trends are probably linked to climate change.[101][102]

Drought

In 2019 the drought and water resources minister of Australia David Littleproud, said, that he "totally accepts" the link between climate change and drought in Australia because he "live it". He says that the drought in Australia is already 8 years long. He called for a reduction in Greenhouse gas emission and massive installation of renewable energy. Former leader of the nationalists Barnaby Joyce said that if the drought became more fierce and dams will not be built, the coalition risk "political annihilation"[69]

Extreme weather events

Globally, the World Meteorological Organization has claimed that extreme weather events are on the rise as a result of human interference in the climate system,[103] and climate models indicate the potential for increases in extremes of temperature, precipitation, droughts, storms, and floods.[104] The CSIRO predicts that a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius on the Australian continent could incur some of the following extreme weather occurrences, in addition to standard patterns:

- Wind speeds of tropical cyclones could intensify by 5 to 10%.[105]

- Tropical cyclone rainfall could increase by 20–30%.

- In 100 years, strong tides would increase by 12–16% along eastern Victoria's coast.[106]

- The forest fire danger indices in New South Wales and Western Australia would grow by 10% and the forest fire danger indices in south, central and north-east Australia would increase by more than 10%.[107][108]

Projected large-scale singularities from climate change

There are a number of issues that could cause a range of direct and indirect consequences to many regions of the world, including Australia. These include large-scale singularities – sudden, potentially disastrous changes in ecosystems brought on gradual changes.[109] The collapse of regional, or even global, coral reef ecosystems is possibly the most significant potential large-scale singularity to Australia. Coral reef ecosystems have a narrow temperature range, meaning that they can rapidly change from being a healthy system to being stressed, bleached, or at worst, eradicated.[110]

Ecosystem changes in other parts of the world could also have serious consequences for climate change for the Australian continent. Evidence from carbon cycle modeling suggests that the deaths of forests in tropical regions might increase the net concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, by converting the terrestrial biosphere from a carbon sink to a source of CO2.[111]

Recently, scientists have expressed concern about the potential for climate change to destabilize the Greenland ice sheet and West Antarctic Ice Sheet.[112] An increase in global temperatures as well as the melting of glaciers and ice sheets (which causes an increase in the volume of freshwater flowing into the ocean), could threaten the balance of the global ocean thermohaline circulation (THC). Such deterioration could cause significant environmental and economic consequences through regional climate shifts in Australia and elsewhere, resulting from change in the global ocean circulation.[113][114] Melting of glaciers and ice sheets also contributes to sea-level rise. Immense quantities of ice are held in the ice sheets of West Antarctica and Greenland, jointly containing the equivalent of approximately 12 meters of sea-level rise. Deterioration or breakdown of these ice sheets would lead to irreversible sea-level rise and coastal inundation across the globe.

The CSIRO predicts that additional singularities caused by a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius will be:

- Beginning of effects on thermohaline circulation (THC).[115]

- Considerable decrease in THC.[116]

- 20–25% decrease in THC.[117]

- 5% possibility of significant change in THC.[114]

- Threshold surpassed for breakdown of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.[112][118]

Projections for Australia's changing climate include:[119]

- Increasingly regular droughts, especially in the southwest,

- Higher evaporation rates, specifically in the north and east,

- Intensifying high-fire-danger weather in the southeast,

- Continually rising sea levels.

Biodiversity and ecosystems

Australia has some of the world's most diverse ecosystems and natural habitats, and it may be this variety that makes them the Earth's most fragile and at-risk when exposed to climate change. The Great Barrier Reef is a prime example. Over the past 20 years it has experienced unparalleled rates of bleaching. Additional warming of 1 °C is expected to cause substantial losses of species and of associated coral communities.[93]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between 2 and 3 degrees Celsius will be:

- 97% of the Great Barrier Reef bleached annually.[120]

- 10–40% loss of principal habitat for Victoria and montane tropical vertebrate species.[121]

- 92% decrease in butterfly species' primary habitats.[122]

- 98% reduction in Bowerbird habitat in Northern Australia.[123]

- 80% loss of freshwater wetlands in Kakadu (30 cm sea level rise).[124]

Industry

Agriculture forestry and livestock

Small changes caused by global warming, such as a longer growing season, a more temperate climate and increased CO2 concentrations, may benefit Australian crop agriculture and forestry in the short term. However, such benefits are unlikely to be sustained with increasingly severe effects of global warming. Changes in precipitation and consequent water management problems will further exacerbate Australia's current water availability and quality challenges, both for commercial and residential use.[93]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between 3 and 4 degrees Celsius will be:

- 32% possibility of diminished wheat production (without adaptation).[125]

- 45% probability of wheat crop value being beneath present levels (without adaptation).[125]

- 55% of primary habitat lost for Eucalyptus.[126]

- 25–50% rise in common timber yield in cool and wet parts of S Australia.[127]

- 25–50% reduction in common timber yield in North Queensland and the Top End.[127]

- 6% decrease in Australian net primary production (for 20% precipitation decrease)

- 128% increase in tick associated losses in net cattle production weight.[128]

Water resources

Healthy and diverse vegetation is essential to river health and quality, and many of Australia's most important catchments are covered by native forest, maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Climate change will affect growth, species composition and pest incursion of native species and in turn will profoundly affect water supply from these catchments. Increased re-afforestation in cleared catchments also has the prospect for water losses.[129]

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between only 1 and 2 degrees Celsius will be:

- 12–25% reduction in flow in the Murray River and Darling River basin.[130]

- 7–35% reduction in Melbourne's water supply.[131]

Public health

The CSIRO predicts that the additional results in Australia of a temperature rise of between only 1 and 2 degrees Celsius will be:[132]

- Southward spread of malaria receptive zones.

- Risk of dengue fever among Australians increases from 0.17 million people to 0.75–1.6 million.

- 10% increase in diarrhoeal diseases among Aboriginal children in central Australia.

- 100% increase in a number of people exposed to flooding in Australia.

- Increased influx of refugees from the Pacific Islands.

Settlements and infrastructure

Global warming could lead to substantial alterations in climate extremes, such as tropical cyclones, heat waves and severe precipitation events. This would degrade infrastructure and raise costs through intensified energy demands, maintenance for damaged transportation infrastructure, and disasters, such as coastal flooding.[93]: 5 In the coastal zone, sea level rise and storm surge may be more critical drivers of these changes than either temperature or precipitation.[93]: 20

The CSIRO describes the additional impact on settlements and infrastructure for rises in temperature of only 1 to 2 degrees Celsius:

- A 22% rise in 100-year storm surge height around Cairns; as a result, the area flooded doubles.[105]

- A 1% decrease in peak electricity demands in Melbourne and Sydney.[133][134]

- 4–10% increase in peak electricity demands in Adelaide and Brisbane.

- 20% increase in methane from bush fires.

Human settlements

Climate change will have a higher impact on Australia's coastal communities, due to the concentration of population, commerce and industry. Climate modelling suggests that a temperature rise of 1–2 °C will result in more intense storm winds, including those from tropical cyclones.[135] Combine this with sea level rise, and the result is greater flooding, due to higher levels of storm surge and wind speed.Coleman, T. (2002) The impact of climate change on insurance against catastrophes. Proceedings of Living with Climate Change Conference. Canberra, 19 December.) Tourism of coastal areas may also be affected by coastal inundation and beach erosion, as a result of sea level rise and storm events. At higher levels of warming, coastal impacts become more severe with higher storm winds and sea levels.

Property

A report released in October 2009 by the Standing Committee on Climate Change, Water, Environment and the arts, studying the effects of a 1-metre sea level rise, possible within the next 30–60 years, concluded that around 700,000 properties around Australia, including 80,000 buildings, would be inundated. The collective value of these properties is estimated at $150 billion.[64]

A 1-metre sea level rise would have massive impacts, not just on property and associated economic systems, but in displacement of human populations throughout the continent. Queensland is the state most at risk due to the presence of valuable beachfront housing.[136]

Adelaide

Adelaide's Hills Face Zone (HFZ) is a steep and rugged escarpment created by the Eden–Burnside Fault, forming the western boundary of the Adelaide Hills. The HFZ contains a number of conservation parks such as Morialta CP and Cleland CP, which support large areas of fire-prone vegetation. The escarpment is cut by a number of very rugged gorges such as the Morialtta Gorge and Waterfall Gully. Development is restricted in the HFZ, with settlement mainly occurring on the uplands east of the escarpment. The roads traversing the escarpment tend to be very narrow and winding, and access or escape routes to some areas of settlement is poor, a factor which affected suburbs such as Greenhill during the 1980 Ash Wednesday bushfires.

The threat of bushfires is very prevalent within the region[137] and poses the threat of spreading into adjacent populated areas.[138]

Sydney

Suburbs of Sydney like Manly, Botany,[139] Narrabeen,[139] Port Botany,[139] and Rockdale,[139] which lie on rivers like the Parramatta, face risks of flooding in low-lying areas such as parks (like Timbrell Park and Majors Bay Reserve), or massive expenses in rebuilding seawalls to higher levels.

Melbourne

Many suburbs of Melbourne are situated around Port Phillip. A sea level rise of 1 m would threaten the surrounding area, including suburban communities. It would also flood all of the city's major cargo shipping docks, surrounding cargo storage areas, the Docklands development and several marinas and berths in Port Phillip. A sea level rise of 1 m would displace around 5–10,000 people and directly impact approximately 60–80,000 people in metropolitan Melbourne/Mornington Peninsula alone.

A sea level rise of 5–10 m would see the CBD at the mouth of the Yarra River and former wetlands entirely flooded, bringing the shoreline back to towns and suburbs such as Kensington, Footscray, Altona North, Prahran, Elsternwick, Dingley, Dandenong South, Pakenham South, Laverton and Lara. Areas completely inundated would include much of the Bellarine Peninsula and Swan Island, parts of Geelong, the Werribee Treatment Plant, all of Altona, Point Cook, Williamstown, West Melbourne, Port Melbourne, South Melbourne, Elwood, Mordialloc, Braeside, Aspendale, Edithvale, Chelsea, Bonbeach, Carrum, Patterson Lakes, Seaford, Frankston North, Safety Beach and parts of Dromana, Rosebud, Rye, Blairgowrie and Sorrento.

A rise of 5–10 m would also disrupt agriculture to the west of Port Phillip and around Geelong, increase the width of the Yarra River back to Hawthorn and the Maribyrnong River back to Avondale Heights. In addition, the MCG would be located precariously close to the wider Yarra River and be subject to flooding. Such a rise would displace roughly 200,000 people in metropolitan Melbourne and the Mornington Peninsula, excluding Geelong and the Bellarine Peninsula.

Transportation

A sea level rise of 1 m would affect roadways near the coast and pose a threat to the Stony Point rail line and West Melbourne dock and cargo lines and yards. Whilst a rise of 5–10 m would cut rail transport among the CBD and the western suburbs and between Melbourne and Geelong. Rail & freeway transportation to the Mornington Peninsula would also be cut off. The rise would submerge the West Gate Freeway, CityLink tunnels, and the northern link of CityLink, rendering the West Gate and Bolte Bridges useless. Bridges over the Yarra & Maribyrnong in the CBD and inner Melbourne would be submerged.

Hobart

A sea water rise of 1.1 m would inundate eight to eleven thousand residential buildings in Tasmania, more than 2500 of those in the Clarence and Kingbourgh local government areas, which are part of Greater Hobart.[140]

Brisbane

The Port of Brisbane and Brisbane Airport would be at risk of inundation from a 1-m rise. A sea level rise of 10 m would almost completely flood Bribie Island. The Gold Coast, being built on low-lying land, particularly parts that were formerly wetlands, including many canal developments, are particularly at risk. A sea level rise of 10 m would completely inundate the Gold Coast.

Environment

Great Barrier Reef

The Great Barrier Reef could be killed as a result of the rise in water temperature forecast by the IPCC. A UNESCO World Heritage Site, the reef has experienced unprecedented rates of bleaching over the past two decades, and additional warming of only 1 °C is anticipated to cause considerable losses or contractions of species associated with coral communities.[93]

Lord Howe Island

The coral reefs of the World Heritage-listed Lord Howe Island could be killed as a result of the rise in water temperature forecast by the IPCC.[141] As of April 2019, approximately 5% of the coral is dead.[142]

Further reading

This section needs to be updated. (November 2019) |

- Burton, Paul 2014, Responding to Climate Change, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, ISBN 9780643108615.

- Goldie, Jenny & Betts, Katharine 2014, Sustainable Futures, CSIRO Publishing, Melbourne, ISBN 9781486301898.

- Spratt, David; Sutton, Philip (2008). "Climate Code Red: The Case for Emergency Action". Australia: Scribe Publications.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Diesendorf, Mark (2007). Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy. Australia: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-973-3.

- Preston, B.L.; Jones, R.N. (February 2006). "Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions". the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change, Australia: CSIRO.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Australian Academy of Science (August 2010). The Science of Climate Change: Questions and Answers (PDF). Canberra: Australian Academy of Science. ISBN 978-0-85847-286-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

- Soils and agriculture

- Clarke, A. L. (1986). "Cultivation". Australian Soils: the Human Impact. Brisbane: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-1968-9.

- Conacher, Arthur; Conacher, Jeannette (1995). Rural Land Degradation in Australia. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-553436-8.

- McLaughlin, M. J.; Fillery, I. R. (1992). "Operation of the phospherous, sulfur and nitrogen cycles". Australia's Renewable Resources: Sustainability and Global Change (Bureau of Rural Resources, Proceedings no. 14). Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-644-14820-7.

- McTainsh, Grant H.; Boughton, Walter C. (1993). Land Degradation Processes in Australia. Melbourne: Longman Cheshire. ISBN 978-0-582-87008-6.

- Roberts, Brian R. (1995). The Quest for Sustainable Agriculture and Land Use. Sydney: UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-374-8.

- Woods, L. E. (1983). Land degradation in Australia. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. ISBN 978-0-644-02615-4.

See also

- 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference

- Adaptation to global warming in Australia

- Beyond Zero Emissions

- Biofuel in Australia

- Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme

- Climate Code Red

- Climate Group

- Climate Institute of Australia

- Climate of Australia

- Coal phase out

- Contribution to global warming by Australia

- Drought in Australia

- Environmental issues in Australia

- Matthew England

- Environment of Australia

- Greenhouse Mafia

- Greenhouse Solutions with Sustainable Energy

- Living in the Hothouse: How Global Warming Affects Australia, a 2005 book by Ian Lowe

- Effect of climate change on plant biodiversity

- Effects of global warming on oceans

- El Niño–Southern Oscillation

- IPCC Fifth Assessment Report

- Mitigation of global warming in Australia

- Physical impacts of climate change

- Water restrictions in Australia

References

- ^ Scientists Trace Extreme Heat in Australia to Climate Change 29 September 2014 NYT

- ^ "CSIRO report says Australia getting hotter with more to come". ABC Online. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- ^ "State of the Climate 2014". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 29 March 2014.

- ^ Lindenmayer, David; Dovers, Stephen; Morton, Steve, eds. (2014). Ten Commitments Revisited. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486301676.

- ^ Johnston, Tim (3 October 2007). "Climate change becomes urgent security issue in Australia". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 June 2011.

- ^ "Hasta la vista El Nino – but don't hold out for 'normal' weather just yet". The Conversation. 28 January 2016. Retrieved 22 February 2016.

- ^ "Regional Rainfall Trends". Commonwealth of Australia Bureau of Meteorology. 2011. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Lean, Geoffrey; Marks, Kathy (1 February 2009). "Parched: Australia faces collapse as climate change kicks in". The Independent. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ "Recent Changes". Climate Change in Australia. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- ^ "Big fall in electricity sector emissions since carbon tax". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ^ "Corporate Australia in denial about climate change, former coal exec Ian Dunlop says". ABC. 15 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ^ Taylor, Maria (2014). Global Warming and Climate Change: What Australia knew and buried...then framed a new reality for the public. Canberra: Australian National University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9781925021905.

- ^ "Australia votes to repeal carbon tax". BBC News. 17 July 2014. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Malcolm Turnbull must end uncertainty over renewable energy target". Sydney Morning Herald. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ a b "What will the Paris climate deal mean for Australia?". 13 December 2015.

- ^ "Environment & Heritage Climate change". Office of Environment and Heritage. New South Wales Government. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ "Understanding Climate Change". Department of Sustainability and Environment. State Government of Victoria. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "Office of Climate Change". Queensland Government. 4 July 2011. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ "What is climate change? –". Government of South Australia. 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ http://www.dec.wa.gov.au/our-environment/climate-change/index.html Climate Change (WA) Retrieved 27-01-2009

- ^ http://www.climatechange.tas.gov.au/ (Tas) Retrieved 27-01-2009

- ^ http://www.nt.gov.au/dcm/legislation/climatechange/ Archived 24 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine Climate Change (NT) Retrieved 27-01-2009

- ^ "Climate Change". Department of the Environment, Climate Change, Energy and Water. Australian Capital Territory Government. 3 September 2011. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ Steve Skitmore. The New Climate Wedge: Farmers vs Coal Mining. Friends of the Earth Australia.

- ^ Andrew Fowler (13 April 2010). Coal town's doctors raise child health alarm. ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Campaigns. Rising Tide Australia.

- ^ "Garnaut Climate Change Review Interim Report to the Commonwealth, State and Territory Governments of Australia" (PDF). Garnaut Climate Change Review. February 2007. pp. 63pp. Retrieved 27 April 2008.

These glimpses suggest that it is in Australia's interest to seek the strongest feasible global mitigation outcomes – 450 ppm as currently recommended by the science advisers to the UNFCCC and accepted by the European Union. (p25)

- ^ Murphy, Katharine (25 September 2019). "Scott Morrison says Australia's record on climate change misrepresented by media". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ Pittock, Barrie, ed. (2003). Climate Change: An Australian Guide to the Science and Potential Impacts (PDF). Commonwealth of Australia: Australian Greenhouse Office. ISBN 978-1-920840-12-9.

- ^ "Australasia".

- ^ Flannery, Tim, The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australian Lands and People; p. 115 ISBN 0-8021-3943-4

- ^ Water Research Foundation of Australia; 1975 symposium: the 1973-4 floods in rural and urban communities; seminar held in August 1976 by the Victorian Branch of the Water Research Foundation of Australia.

- ^ Allen, R. J.; The Australasian Summer Monsoon, Teleconnections, and Flooding in the Lake Eyre Basin; pp. 41–42. ISBN 0-909112-09-6

- ^ Bourke, Patricia; Brockwell, Sally; Faulkner, Patrick and Meehan, Betty; "Climate variability in the mid to late Holocene Arnhem Land region, North Australia: archaeological archives of environmental and cultural change" in Archaeology in Oceania; 42:3 (October 2007); pp. 91–101.

- ^ Water Research Foundation of Australia; 1975 symposium

- ^ Lough, J. M. (2007), "Tropical river flow and rainfall reconstructions from coral luminescence: Great Barrier Reef, Australia", Paleoceanography, 22, PA2218, doi:10.1029/2006PA001377.

- ^ Warner, R. F.; "The impacts of flood- and drought-dominated regimes on channel morphology at Penrith, New South Wales, Australia". IAHS Publ. No. 168; pp. 327–338, 1987.

- ^ Green, H.J.; Results of rainfall observations made in South Australia and the Northern Territory: including all available annual rainfall totals from 829 stations for all years of recording up to 1917, with maps and diagrams: also appendices, presenting monthly and yearly meteorological elements for Adelaide and Darwin; published 1918 by Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ Gibbs, W.J. and Maher, J. V.; Rainfall deciles as drought indicators; published 1967 by Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ Hunt, H.A. Results of rainfall observations made in Queensland: including all available annual rainfall totals from 1040 stations for all years of record up to 1913, together with maps and diagrams; published 1914 by Commonwealth Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ "Commentary on rainfall probabilities based on phases of the SOI". www.longpaddock.qld.gov.au. Department of Environment and Resource Management. Archived from the original on 1 August 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ashcroft, Linden; Gergis, Joëlle; Karoly, David John (November 2014). "A historical climate dataset for southeastern Australia, 1788-1859". Geoscience Data Journal. 1 (2): 158–178. Bibcode:2014GSDJ....1..158A. doi:10.1002/gdj3.19.

- ^ Foley, J.C.; Droughts in Australia: review of records from earliest years of settlement to 1955; published 1957 by Australian Bureau of Meteorology

- ^ Allan, R.J.; Lindesay, J. and Parker, D.E.; El Niño, Southern Oscillation and Climate Variability; p. 70. ISBN 0-643-05803-6

- ^ Soils and landscapes near Narrabri and Edgeroi, NSW, with data analysis using fuzzy k-means

- ^ Fewer frosts. Bureau of Meteorology.

- ^ "Annual Australian Climate Statement 2009". Australian Bureau of Meteorology. 5 January 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

- ^ Hot and Dry: Australia's Weird Winter BY LESLEY HUGHES 18.09.2017

- ^ a b "Australia in Summer 2013–14". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Melbourne in Summer 2014". Buearu of Meteorology. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ^ "Annual Climate Report 2015". Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

- ^ "Circulation features associated with the winter rainfall decrease in southwest Western Australia" (PDF).

- ^ CSIRO (2006). Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Archived 25 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CSIRO (2007), Climate change in Australia: Technical report 2007, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Canberra; Preston, B. and Jones, R. (2006), Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A consultancy report for the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change, CSIRO, Canberra.

- ^ http://climatecommission.gov.au/resources/commission-reports/ Climate Commission reports.

- ^ a b Peel, Jacquiline; Osofsky, Hari (2015). Climate Change Litigation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781107036062.

- ^ The Critical Decade: Extreme Weather Climate Commission Australia.[dead link]

- ^ "key facts" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2013.

- ^ Climate change making extreme events worse in Australia – report The Guardian 2.4.2013

- ^ Sivakumar, Mannava; Motha, Raymond (2007). Managing Weather and Climate Risks in Agriculture. Berlin: Springer. p. 109. ISBN 9783540727446.

- ^ DCC (2009), Climate Change Risks to Australia's coasts, Canberra.

- ^ a b Glavovic, Bruce; Kelly, Mick; Kay, Mick; Travers, Aibhe (2014). Climate Change and the Coast: Building Resilient Communities. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 257. ISBN 9781482288582.

- ^ Australia's Low Pollution Future: The Economics of Climate Change Mitigation Archived 18 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Herald Sun, "Victoria's Stormy Forecast", Oct, 28, 2009

- ^ Anderson, Deb (2014). Endurance. CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 9781486301201.

- ^ Australian rivers 'face disaster', BBC News

- ^ Saving Australia's water, BBC News

- ^ Metropolis strives to meet its thirst, BBC News

- ^ a b Katharine Murphy, Katharine (6 October 2019). "Water resources minister 'totally' accepts drought linked to climate change". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- ^ "Australian Greenhouse Office". Australian Competition and Consumer Commission. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ^ "Interview Prime Minister of Australia". Prime Minister of Australia's website. Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, Canberra, Australia. 27 April 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ "Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme" (Press release). Australian Government Department of Climate Change and Energy. 5 May 2010. Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- ^ Kelly, Joe (28 April 2010). "Tony Abbott accuses Kevin Rudd of lacking 'guts' to fight for ETS". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ^ Hartcher, Peter (1 May 2010). "It's time for Labor to fret". The Age. Melbourne.

- ^ "Emissions trading schemes around the world". www.aph.gov.au. Commonwealth Parliament.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ editor, Katharine Murphy Political (15 October 2017). "Dumping clean energy target is 'dealbreaker' for Labor's support". Retrieved 18 October 2017 – via www.TheGuardian.com.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Cabinet dumps Finkel's energy proposal for 'affordable, reliable' power plan". ABC.net.au. 16 October 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ^ Hanna, Emily. "Climate change—reducing Australia's emissions". Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ "Rann's climate change laws a first for Australia". Conservation Council of South Australia. 3 March 2006. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ Rann, Mike (4 April 2012). "What States Can Do – Part I: Climate Change Policy". The Center for National Policy. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Munro, Peter: "Big numbers warm to climate cause", in The Age, 13 December 2009

- ^ Climate Change Despair & Empowerment Roadshow Australia. Retrieved on 6 July 2011.

- ^ (5 June 2011). Thousands 'Say Yes' at carbon price rallies. ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Climate Witness in Action. WWF. Retrieved on 6 July 2011.

- ^ (5 July 2005). Churches and conservationists tackle climate change. Australian Conservation Foundation.

- ^ Kathryn Roberts (16 February 2007)Mining giant wins global warming court case/ World Today. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ (12 February 2007)No arrests made during climate change protest Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine. ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ^ Clean energy future. WWF Australia.

- ^ Advocacy & ChangeMakers Archived 15 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. TEAR Australia.

- ^ Check, RMIT ABC Fact (24 October 2019). "Fact Check zombie: Angus Taylor repeats misleading claim on carbon emissions yet again". ABC News. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ a b Which nations are really responsible for climate change – interactive map The Guardian 8.12.2011 (All goods and services consumed, source: Peters et al PNAS, 2011)

- ^ a b c d e f Preston, B. L.; Jones, R. N. (2006). Climate Change Impacts on Australia and the Benefits of Early Action to Reduce Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A consultancy report for the Australian Business Roundtable on Climate Change (PDF). CSIRO.

- ^ Pearce, Karen; Holper, Paul; Hopkins, Mandy; Bouma, Willem; Whetton, Penny; Hennessy, Kevin; Power, Scott, eds. (2007). Climate Change in Australia: Technical Report 2007. CSIRO. ISBN 978-1-921232-94-7.

- ^ Marshall, Peter (12 February 2009). "Face global warming or lives will be at risk". Melbourne: The Age Newspaper. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "CLIMATE CHANGE AND ITS IMPACT ON THE MANAGEMENT OF BUSHFIRE" (PDF). Bushfire Cooperative Research Centre. September 2006. p. 4. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ "Climate change impacts on fire-weather in south-east Australia" (PDF). CSIRO Marine and Atmospheric Research, Bushfire CRC and Australian Bureau of Meteorology. December 2005. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b "Black Saturday Royal Commission". The Age. Melbourne. 31 July 2010.

- ^ "More than 1,800 homes destroyed in Vic bushfires". ABC News Australia. 13 February 2009. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (9 February 2009). "Why Global Warming May Be Fueling Australia's Fires". Time. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ^ Price, Owen (17 August 2018). "Drought, wind and heat: Bushfire season is starting earlier and lasting longer". ABC news. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Woodburn, Joanna (8 August 2018). "NSW Government says entire state in drought, new DPI figures reveal full extent of big dry". ABC news. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ World Meteorological Organisation (2003). Press release, Geneva, Switzerland, 2 July.

- ^ IPCC (2001). Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. McCarthy, J., Canziani, O., Leary, N., Dokken, D and White, K. (eds). Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, World Meteorological Organisation and United Nations Environment Programme. Cambridge University Press, 1032 pp.

- ^ a b McInnes, K.L., Walsh, K.J.E., Hubbert, G.D., and Beer, T. (2003) Impact of sea-level rise and storm surges on a coastal community. Natural Hazards 30, 187–207

- ^ McInnes, K.L., Macadam, I., Hubbert, G.D., Abbs, D.J., and Bathols, J. (2005) Climate Change in Eastern Victoria, Stage 2 Report: The Effect of Climate Change on Storm Surges. A consultancy report undertaken for the Gippsland Coastal Board by the Climate Impacts Group, CSIRO Atmospheric Research

- ^ Williams, A.A., Karoly, D.J., and Tapper, N. (2001) The sensitivity of Australian fire danger to climate change. Climatic Change 49, 171–191