Culture of Nigeria

| This article is part of a series in |

| Culture of Nigeria |

|---|

|

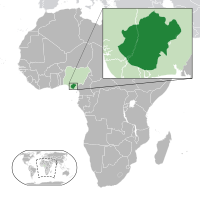

The culture of Nigeria is shaped by Nigeria's multiple ethnic groups.[1][2] The country has 527 languages,[3][4] seven of which are extinct.[5][6][7] Nigeria also has over 1150 dialects and ethnic groups. The three largest ethnic groups are the Hausas that are predominantly in the north, the Yorubas who predominate in the southwest, and the Igbos in the southeast.[8][9][10][11] There are many other ethnic groups with sizeable populations across the different parts of the country. The Kanuri people[12] are located in the northeast part of Nigeria, the Tiv people[13] of north central and the Efik-Ibibio[14] are in the south South. The Bini people[15][16] are most frequent in the region between Yorubaland and Igboland.[17][18]

Nigeria's other ethnic groups, sometimes called 'minorities', are found throughout the country but especially in the north and the middle belt. The traditionally nomadic Fulani can be found all over West and Central Africa.[19] The Fulani and the Hausa are almost entirely Muslim, while the Igbo are almost completely Christian and so are the Bini and the Ibibio. The Yoruba make up about 21% of the country's population – estimated to be over 225 million – and are predominantly Muslim, with a notable Christian minority and a smaller presence of traditionalists.[20][21][22] Indigenous religious practices remain important to all of Nigeria's ethnic groups however, and frequently these beliefs are blended with Christian or Muslim beliefs, a practice known as syncretism.[23]

History[edit]

Major ethnic cultures[edit]

Bini culture[24][edit]

The Binis, also called the Edo people,[25] are a people of the South South region of modern Nigeria; they are said to be around 3.8 million as of the 21st Century. They are ruled by monarchs, and are famous for their Benin Bronzes. In the pre-colonial period, they controlled a powerful empire.[26][27] They are an ethnic group that is primarily found in Edo State, and spread across the Delta, Ondo, and Rivers states of Nigeria in smaller concentrations. The language they speak is called the Edo language. The Bini people are closely related to several other ethnic groups that usually speak Edoid languages, for example the Esan, however it is important to address the fact that the name "Benin" (and "Bini") is a Portuguese corruption, which came from the word "Ubinu", which came into use during the reign of Oba Ewuare the Great, c. 1440. The word "Ubinu" was used to depict and portray the royal administrative centre or capital proper of the kingdom, Edo. The word "Ubinu" was later corrupted to Bini by a number of mixed ethnicities staying together at the centre, and it was then further corrupted to Benin around the year 1485 at the time when the Portuguese people started making trade relations with Oba Ewuare.[28][29]

Hausa-Fulani culture[30][edit]

The Hausa and Fulani ethnic groups are said to be one of the largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, if not the largest, with a population of over 20 million people. The Hausa and Fulani live in the northern part of Nigeria. They are both different tribes, but are often counted as one due to cultural similarity. The bulk of the Hausa-Fulani population is mainly centered in and around the central of Sokoto, Kano and Katsina, which are said to be important market centers on the southern area of the trans-Saharan caravan trade routes.

Long before the arrival of the Fulani people, the Hausa had already formed and made well-organised city states; some of these states include Katsina, Daura, Kano, Zazzau (Zaria), Biram, Gobir and Borno. However, some of these states were conquered, taken over and re-established by the Fulani people which then led to the formation of a few other kingdoms such as Katagum, Hadejia and Gombe. The arrival of the Fulani people into Hausaland brought about great changes in the land, which included the reformation of Islam. This then ended up playing a significant role in the social life and culture of the Hausa people. In education, dress and taste, the Hausa people and their counterparts the Fulani have become a significant part of the Islamic world; this said influence still remains until the current day.[31] The Fulani practice the art of whipping a suitor before giving his bride to him as part of their marriage obligation. This particular obligation has helped to increase the practice of monogamy among themselves, and it is called Sharo.[32] The Fulani people are also nomadic in nature; this nomadic lifestyle spread them into virtually all of West Africa. They are extremely tolerant of the languages of other people around them, leading to the suppression of theirs - especially in northern Nigeria by Hausa.[33][34]

The Hausas, on the other hand, are said to be very good merchants. This helped spread them to some areas around Nigeria.[35] They have monarchs, are known for celebrating the Hawan Sallah festival,[36] and are also followers of the religious teachings of Sheikh Usman dan Fodio.[37]

Igbo culture[38][edit]

The Igbo people, commonly and often referred to as Ibo people, are one of the largest ethnic groups to ever exist in Africa; they have a total population of about 20 million people. Most people who are a part of this ethnic group are based in the southeastern part of Nigeria, they contribute to about 17 percent of the country's population. They can also be found in large numbers in Cameroon and other African countries. It is believed that the Igbo people originated in an area that is about 100 miles north of their current location at the confluence of the Niger and Benue Rivers. The Igbo people share linguistic ties with their neighbours the Bini, Igala, Yoruba, and Idoma, with whom it is believed they were closely related until five to six thousand years ago.[citation needed] The first Igbo in the region may have moved onto the Awka-Orlu plateau between four and five thousand years ago. The eastern part of Nigeria is the home of the Igbos, who are mostly Christians.[39] Their traditional religion is known as Omenani/Omenala. Both concepts, each an aspect of a single whole, aspire to protect and preserve the purity, sanctity and sacredness of the land and the people therein. 'Omenana' is man-made; it is easily changed and is adaptable. 'Odinana', on the contrary, is a code of life, handed down from Chukwu, God the Creator, to Eri, the patriarch of the Igbo race, to prevent chaos and confusion. The earth spirit, Ana, is 'Odinana', as is the sacred role of yam in the Igbo world, the right of inheritance, and the place of the elder. 'Odinana', as the immutable customary rites and traditions of the Igbo world, is enduring and cuts across indigenous Igbo people, while 'Omenana' is rather relative from one section of the Igbo to the other.[40][41] Socially, the Igbos are led by monarchs who had limited power historically. These figures are expected to confer subordinate titles upon men and women that are highly accomplished. This is known as the Nze na Ozo title system.[42][43]

Ijaw culture[edit]

The Ijaw people are said to be a collection of people that are native to the Niger Delta area in Nigeria. Owing to the affinity they have with water, a significant number of the Ijaw people are discovered as migrant fishermen in camps that are as far west as Sierra Leone and as far east as Gabon.[44] With a population of about 4 million, the Ijaws inhabit the Niger Delta section and they make up about 1.8% of Nigeria's population.[45] From a historical perspective, it is almost impossible to give a precise and accurate account as to when and where the Ijaws originated; numerous different accounts have been given by many historians regarding this issue, but what is certain is that the Ijaws are one of the world's most ancient peoples. The Ijaw people are said by some to be the descendants of the autochthonous people of Africa known as the (H) oru. The Ijaws were originally known by this name (Oru); at least it was what their immediate neighbours assumed them to be. Although this was a very long time ago, the Ijaws have, however, kept the ancient language and culture of the Orus. Being the first to find a settlement in the Lower Niger and Niger Delta, it is possible that they may have started inhabiting this region as far back as 500 BC.[46]

Language and cultural studies suggest that they are related to the founders of the Nile Valley civilization complex (and possibly the Lake Chad complex).[47] They immigrated to West Africa from the Nile Valley during antiquity. The Ijaw culture of the South has been influenced greatly by its location on the coast and the interaction with foreigners that it necessitated. Its members amassed great wealth while serving as middlemen, and the preponderance of English names among them today is a testament to the trade names adopted by their ancestors at this time.[48][49]

Yoruba culture[50][edit]

The Yoruba people are said to be one of the three largest ethnic groups in Nigeria, alongside the Igbo and the Hausa-Fulani peoples. They are concentrated in the southwestern section of Nigeria, much smaller and scattered groups of Yoruba people live in Benin and northern Togo and they are numbered to be more than 20 million at the turn of the 21st century.[51] The Yoruba people have always shared a common language called the Yoruba language and have had the same culture for hundreds of years now, but historically they were less likely to be a single political unit prior to the colonial period.[52] The Yoruba people are believed to have migrated from the east to their present lands west of the lower Niger River more than a millennium ago.[53] They eventually became the most urbanized Africans of precolonial times. The Yoruba people eventually formed many kingdoms of various different sizes, each of which was centered on a capital city or town and was ruled by a hereditary king known as an oba. Their towns eventually became more and more populated and grew into the present-day cities of Oyo, Ile-Ife, Ilesha, Ibadan, Ilorin, Ijebu-Ode, Ikere-Ekiti, and others.[54] Oyo developed in the medieval and early modern periods into the largest of the Yoruba kingdoms, while Ile-Ife still remained a town of very strong religious significance as the site of the earth's creation according to Yoruba mythology.[55] Oyo and the other kingdoms declined in the late 18th and 19th centuries owing to disputes among minor Yoruba rulers and invasions by the Fon of Dahomey (now Benin Republic) and the Muslim Fulani. The traditional Yoruba kingships still survive, but with only a hint of their former political power. These monarchs have titled individuals that serve beneath them, with most of this latter group making up the membership of the Ogboni secret society. Their traditional religion, Ifa, has been recognized by UNESCO as a masterpiece of the oral tradition of Humanity.[56]

Nigerian upper class[edit]

Ever since the country's earliest centralization - under the Nokites at a time contemporaneous to the birth of Jesus Christ - Nigeria has been ruled by a class of titled potentates that are known as chiefs.[57] Led by the Nigerian traditional rulers (i.e. monarchs who have received definite authority from the official government and are recognized by the laws of Nigeria),[58] the chiefs come in various ranks and are of varied kinds - some monarchs are so powerful that they influence political and religious life outside their immediate domains (the Sultan of Sokoto and the Ooni of Ife, for example), while in contrast many local families around the country install their eldest members as titled chiefs in order for them to provide them with what is an essentially titular leadership.[59]

Although chiefs have few official powers today, they are widely respected, and prominent monarchs are often courted to endorse politicians during elections in the hopes of them conferring legitimacy to their campaigns by way of doing so. Successful Nigerians, such as businessmen and the said politicians, typically themselves aspire to the holding of chieftaincies, and the monarchs' control of the honours system that provides them serves as an important royal asset.[60]

Literature[edit]

Nigeria is famous for its English language literature. Things Fall Apart,[61] by Chinua Achebe, is an important book in African literature.[62] With over eight million copies sold worldwide, it has been translated into 50 languages, making Achebe the most translated African writer of all time.[63][64]

Nigerian Nobel laureate[65] Wole Soyinka[66] described the work as "the first novel in English which spoke from the interior of the African character, rather than portraying the African as an exotic, as the white man would see him."[67] Nigeria has other notable writers of English language literature. These include Femi Osofisan,[68] whose first published novel, Kolera Kolej, was produced in 1975; Ben Okri, whose first work, The Famished Road, was published in 1991, and Buchi Emecheta, who wrote stories drawn from her personal experiences of gender inequity that promote viewing women through a single prism of the ability to marry and have children. Helon Habila, Sefi Atta , Flora Nwapa, Iquo Diana Abasi Eke,[69] Zaynab Alkali and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie,[70] among others, are notable Nigerian authors whose works are read widely within and outside the country.[71]

Apart from the speakers of standard English, a large portion of the population, roughly a third, speaks Nigerian pidgin, which has a primarily English lexicon. It has become a common lingua franca as a result. Pidgin English is a creolized form of the language. For instance, "How you dey" means "How are you". The Palm Wine Drinkard, a popular novel by Amos Tutuola, was written in it.

Film[edit]

Since the 1990s the Nigerian movie industry, sometimes called "Nollywood", has emerged as a fast-growing cultural force all over Africa. Vast wealth has been generated by it, and it is currently the second-largest film industry in the world by output.[citation needed]

Because of the movies, western influences such as music, casual dressing and methods of speaking are to be found all across Nigeria, even in the highly conservative north of the country.[72]

Media[edit]

Sports[edit]

The Nigerian national football team,[73] nicknamed the "Super Eagles", is the national team of Nigeria, run by the Nigeria Football Federation (NFF). According to the FIFA World Rankings, Nigeria ranks 42nd and holds the sixth-highest place among the African nations. The highest position Nigeria ever reached on the ranking was 5th, in April 1994.

Supporters of English football clubs like Manchester United, Arsenal, Manchester City, Liverpool and Chelsea often segregate beyond the traditional tribal and even religious divide to share their common cause in Premier League teams.

Other than football, basketball, handball and volleyball are also prominent in the Nigerian sports sector. Indigenous games such as loofball, dambe and ayo also have significant popularity among youths in Nigeria.

Nigeria is the country of origin for the sport Loofball. The game involves two teams of five, a ball, and a net. It is played by tossing the ball over the net to the opposing team's side of the court.[74] After July of 2021, the sport has been administered by the LSDI (Loofball Sports Development Initiative).[75]

Architecture[edit]

Food[edit]

Nigerian food offers a rich blend of traditionally African carbohydrates such as yam and cassava as well as the vegetable soups with which they are often served. Maize is another crop that is commonly grown in Nigeria.[76] Praised by Nigerians for the strength it gives, garri is "the number one staple carbohydrate food item in Nigeria",[77] a powdered cassava grain that can be readily eaten as a meal and is quite inexpensive. Yams are frequently eaten either fried in oil or pounded to make a mashed potato-like yam pottage. Nigerian beans, quite different from green peas, are widely popular. Meat is also popular and Nigerian suya—a barbecue-like roasted meat—is a well-known delicacy. Bushmeat, meat from wild game like antelope and duikers, is also popular. Fermented palm products make a traditional liquor, palm wine, and also fermented cassava. Nigerian foods are spicy, mostly in the western and southern part of the country, even more so than in Indian cuisine. Other examples of their traditional dishes are eba, pounded yam, iyan, fufu and soups like okra, ogbono and egusi. Fufu is so emblematic of Nigeria that it figures in Chinua Achebe's Things Fall Apart, for example.[78]

Nigeria is known for its many traditional dishes. Each tribe has different dishes that are unique to their culture. Yoruba people, for example, have different dishes like Amala, Ogbono, Moin Moin, Ofada Rice, and Efo Riro.[79]

Music[edit]

The music of Nigeria includes many kinds of folk and popular music, some of which are known worldwide. The singer and social activist Fela Kuti was instrumental in Nigeria's musical development. His personalized sound, dubbed Afrobeat, is now one of the continent's most widely recognised genres.[80]

Traditional musicians use a number of diverse instruments, such as Gongon drums. The kora and the kakaki are also important.[81]

Other traditional cultural expressions are found in the various masquerades of Nigeria, such as the Eyo masquerades of Lagos, the Ekpe and Ekpo masquerades of the Efik/Ibibio/Annang/Igbo people of the South-South and southeastern Nigeria, and the Northern masquerades of the Bini. The most popular Yoruba manifestations of this custom are the Gelede masquerades.[82]

Clothing[edit]

Women wear long flowing robes and headscarves made by local makers who dye and weave the fabric locally.[83] Southern Nigerian women choose to wear western-style clothing. People in urban regions of Nigeria dress in western style, the youth mainly wearing jeans and T-shirts. Other Nigerian men and women typically wear a traditional style called Buba. For men the loose-fitting shirt goes down to halfway down the thigh. For women, the loose-fitting blouse goes down a little below the waist. Other clothing gear includes a gele, which is the woman's headgear. For men their traditional cap is called fila.

Historically, Nigerian fashion incorporated many different types of fabrics. Cotton has been used for over 500 years for fabric-making in Nigeria. Silk (called tsamiya in Hausa, sanyan in Yoruba, and akpa-obubu in Igbo) is also used.[84] Perhaps the most popular fabric used in Nigerian fashion is Dutch wax print, produced in the Netherlands. The import market for this fabric is dominated by the Dutch company Vlisco,[85] which has been selling its Dutch wax print fabric to Nigerians since the late 1800s, when the fabric was sold along the company's oceanic trading route to Indonesia. Since then, Nigerian and African patterns, colour schemes, and motifs have been incorporated into Vlisco's designs to become a staple of the brand.[86]

Nigeria has over 250 ethnic groups[87] and as a result, a wide variety of traditional clothing styles. In the Yoruba tradition, women wear an iro (wrapper), buba (loose shirt) and gele (head-wrap).[88] The men wear buba (long shirt), sokoto (baggy trousers), agbada (flowing robe with wide sleeves) and fila (a hat).[89] In the Igbo tradition, the men's cultural attire is Isiagu (a patterned shirt), which is worn with trousers and the traditional Igbo men's hat called Okpu Agwu. The women wear a puffed sleeved blouse, two wrappers and a headwrap.[90] Hausa men wear barbarigas or kaftans (long flowing gowns) with tall decorated hats. The women wear wrappers and shirts and cover their heads with hijabs (veils).[91]

Oral tradition[edit]

Oral traditions in Nigeria are part of a form of human communication in which knowledge, art ideas, and cultural materials are acquired, conserved, and conveyed orally from one generation to another.[92] It is one of the earliest works from Nigeria put into writing and entails several genres of indigenous knowledge production communicated to its adherents verbally.[93] It also encompasses the transmission of historical and artistic information from an initial witness through generation (the information is handled by skilled oral historians).

Traditions have evolved along with the societies and cultures that produced them. Oral traditions in Nigeria have played a very important role in preserving and transmitting historical information and its various functions. Historical information is usually transmitted through speech, songs, folktales, prose, chants, and ballads. Oral traditions in Nigeria are commonly used as a means of keeping the past alive.[94][95]

Resources[edit]

A very important source of information on modern Nigerian art is the Virtual Museum of Modern Nigerian Art operated by the Pan-Atlantic University in Lagos.

In addition, the Nigerian Investment Promotion Commission, and Naija Invest Gateway, provide real-time information on the Nigerian business culture.

See also[edit]

- Architecture of Nigeria

- Festivals in Nigeria

- Gender roles and fluidity in indigenous Nigerian cultures

- List of museums in Nigeria

- Music of Nigeria

- Nok culture

References[edit]

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2013) |

- ^ Nwafor (11 August 2022). "Nigerian cultural values are under threat, Toyin Falola, US scholar, warns". Vanguard News. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Culture – Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Nigeria". Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Culture – Embassy of the Federal Republic of Nigeria to the Republic of Korea". Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ "Language data for Nigeria". Translators without Borders. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Nigeria: most common languages spoken at home 2020". Statista. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2016). "Nigeria". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (19th ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International Publications.

- ^ omotolani (26 February 2018). "There are 27 languages close to extinction in Nigeria". Pulse Nigeria. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Release, Press (22 April 2019). "Igbos, Yorubas have historical ties - Ooni of Ife". Premium Times Nigeria. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Times, Premium (10 August 2022). "Nigeria: The politics of religion in a transitional society, By Rotimi Akeredolu". Premium Times Nigeria. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Walubengo, Peris (8 October 2022). "Major tribes in Nigeria and their states with all the details". Legit.ng - Nigeria news. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ vanguard (10 May 2017). "Full list of all 371 tribes in Nigeria, states where they originate". Vanguard News. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Al-amin, Usman (2021). "Tooth Dyeing Tradition among the Kanuri Speaking People of Borno, Nigeria". Journal of Science, Humanities and Arts - JOSHA. 8 (5). doi:10.17160/josha.8.5.789. ISSN 2364-0626. S2CID 244142418.

- ^ "Tiv | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Efik | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ brandtner, krista (26 December 2018). "Bini People - Discover African Art". Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Edo | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Release, Press (22 April 2019). "Igbos, Yorubas have historical ties - Ooni of Ife". Premium Times Nigeria. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Lagos, Port Harcourt, Kaduna and Enugu: Tale of four cities The Nation Newspaper". 27 October 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Fulani | People, Religion, & Nigeria | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Conversation, The (21 July 2022). "Islam has a small presence in Nigeria's Igbo region: what a new Quran translation offers". Premium Times Nigeria. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ "Christianity in Nigeria". rpl.hds.harvard.edu. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ Peel, J. D. Y. (1967). "Religious Change in Yorubaland". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 37 (3): 292–306. doi:10.2307/1158152. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1158152. S2CID 145810423.

- ^ "Chrislam: Defying Nigeria's Religious Boundaries". www.leidenislamblog.nl. 17 July 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Edo | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Edo | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "Kingdom of Benin". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Zeijl, Femke van. "The Oba of Benin Kingdom: A history of the monarchy". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ "Benin: The hallowed culture of one of the world's most ancient people". Pulse Nigeria. 20 August 2020. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ brandtner, krista (26 December 2018). "Bini People - Discover African Art". Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Hausa-Fulani". rpl.hds.harvard.edu. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ omotolani (18 July 2022). "Fulani and Hausa: What's the difference?". Pulse Nigeria. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "The men who get whipped to find a wife". BBC News. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Ibrahim, Mustafa B. (1966). "The Fulani - A Nomadic Tribe in Northern Nigeria". African Affairs. 65 (259): 170–176. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a095498. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 720512.

- ^ omotolani (18 July 2022). "Fulani and Hausa: What's the difference?". Pulse Nigeria. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Hausa | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Mahmud Lalo (12 October 2008). "Nigeria: The Durbar on the Plateau". allAfrica. Los. Daily Trust.

- ^ "Usman dan Fodio | Fulani leader | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Igbo | Culture, Lifestyle, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Widjaja, Michael. "Igbo Religion". igboguide.org. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Ezekwugo, Charles M. (1991). "Omenana and Odinana in the Igbo World: A Philosophical Appraisal". Africana Marburgensia. 24 (2): 3–18.

- ^ Madu, Simon Onyekachi. "ODINANI (OMENALA)- IGBO CONCEPT OF LAW AND MORALITY-signed.pdf".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ejikemeuwa J. O. Ndubisi, PhD; Okere, Joseph Ejimogu (2020). "NZE NA OZO TITLE IN IGBO CULTURE: A PHILOSOPHICAL REFLECTION ON ITS SIGNIFICANCE IN A CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY". Oracle of Wisdom Journal of Philosophy and Public Affairs (OWIJOPPA). 4 (3).

- ^ Madukasi, Francis Chuks (30 May 2018). "Ozo Title: An Indigenous Institution In Traditional Religion That Upholds Patriarchy In Igbo Land South-Eastern Nigeria". International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention. 5 (5): 4640–4652. doi:10.18535/ijsshi/v5i5.02. ISSN 2349-2031.

- ^ "Ijaw Culture: A brief walk into the lives of one of the world's most ancient people". Pulse Nigeria. 18 November 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "ijaw people - ethnic group ❂❂ - gospelflavour". gospelflavour.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Showcasing The Ijaw Culture and People of Bayelsa from South-South Nigeria - Courtesy The Scout Association of Nigeria | World Scouting". sdgs.scout.org. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "BRIEF HISTORY OF THE IJO PEOPLE – Ijaw (IZON) World Studies". Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Ijo | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "BRIEF HISTORY OF THE IJO PEOPLE – Ijaw (IZON) World Studies". Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Yoruba | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Yoruba | people | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ Lloyd, P. C. (1954). "The Traditional Political System of the Yoruba". Southwestern Journal of Anthropology. 10 (4): 366–384. doi:10.1086/soutjanth.10.4.3628833. ISSN 0038-4801. JSTOR 3628833. S2CID 155216664.

- ^ Sheba, Eben (2007). "The Ìkál (Yorùbá, Nigeria) Migration Theories and Insignia". History in Africa. 34: 461–468. doi:10.1353/hia.2007.0019. ISSN 0361-5413. S2CID 161960773.

- ^ Adediran, Biodun (21 February 2013), "3. The Dynastic Origins of Western Yorùbá Kingdoms", The Frontier States of Western Yorubaland : State Formation and Political Growth in an Ethnic Frontier Zone, African Dynamics, Ibadan: IFRA-Nigeria, pp. 55–80, ISBN 979-10-92312-14-0, retrieved 21 December 2022

- ^ "Untitled Document". www.laits.utexas.edu. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ^ "Yoruba culture".

- ^ "Traditional rulers and Nigerian unity". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Traditional rulers and Nigerian unity". The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News. 4 June 2021. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "In pictures: Country of kings, Nigeria's many monarchs". BBC News. 13 October 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Ewokor, Chris (1 August 2007). "Nigerians go crazy for a title". BBC News. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ^ "Things Fall Apart | Summary, Themes, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Booker, p. xvii.

- ^ Yousaf, p. 34.

- ^ Ogbaa, p. 5.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1986". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Literature 1986". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Chinua Achebe of Bard College". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. 33 (33): 28–29. Autumn 2001. doi:10.2307/2678893. JSTOR 2678893.

- ^ "Femi Osofisan, Biography". www.mynigeria.com. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Okiche, Ifediora (1 March 2018). "Contemporary African Poetry: A Postcolonial Reading of Iquo Eke's Symphony of Becoming and Ifeanyi Nwaeboh's Stampede of Voiceless Ants". Journal of Pan African Studies. 11 (4): 49. ISSN 0888-6601.

- ^ "Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie comes to terms with global fame". newyorker.com. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 3 July 2021.

- ^ Jagoe, Rebecca (16 July 2013). "From Achebe To Adichie: Top Ten Nigerian Authors". Culture Trip. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- ^ Òníkékù, Qûdùs (January 2007). "Nollywood: The Influence of the Nigerian Movie Industry on African Culture". The Journal of Human Communications.

- ^ Strack-Zimmermann, Benjamin. "Nigeria (2022)". National Football Teams. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "About Loofball". Topend Sports. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Luminous Jannamike, Abuja (6 July 2022). "'School sports will help develop talents, build confidence'". vanguardngr. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ^ Akarolo-Anthony, Sally (2013). "Carbonhydrate intake Among Urbanized Adult Nigerians". International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 64 (3): 292–299. doi:10.3109/09637486.2012.746290. PMC 3622806. PMID 23198770.

- ^ "Producing Garri for export". Agricultural Society of Nigeria. 2016.

- ^ Ogbaa, Kalu (1999). Understanding Things Fall Apart. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30294-7.

- ^ Paradise, Author Nomad (10 August 2020). "Nigerian Food: 16 Popular and Traditional Dishes to Try - Nomad Paradise". Retrieved 18 December 2022.

{{cite web}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "Music – Nigerian Community Leeds". Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Kiddiesafricanews (3 October 2020). "Nigeria and its cultural diversity". Kiddies Africa News. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Gelede | African ritual festival | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ^ "Traditional Nigerian Clothing". WorldAtlas. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ "Textile". Archived from the original on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "distinctive African print fabrics | The true original dutch wax prints". Vlisco. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ Young, Robb (14 November 2012). "Africa's Fabric Is Dutch". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ "Nigeria overview Fact Sheet" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020.

- ^ "Yoruba Clothing". Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "The Yoruba tribe of Nigeria and their clothes rich in colors and textures". Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Umu Igbo Alliance". Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Welcome to Amlap Publishing". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ "Importance of Oral Tradition in Nigeria's History". nigerianfinder.com. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ^ academic.oup.com https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/40577/chapter-abstract/348081120?redirectedFrom=fulltext. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "The rich history of oral tradition in Africa - Right for Education". 4 July 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Importance of Oral Tradition in Nigeria's History". nigerianfinder.com. 24 June 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- Ross, Will. "Nigeria's thriving art and music scene." (Archive) BBC. 20 November 2013.

- "Interesting Facts About Nigerian People and Culture". Answers Africa. 11 June 2013. Retrieved 6 February 2016.

- "People & Culture". ourafrica.org. Retrieved 6 February 2016.