Damon Hill

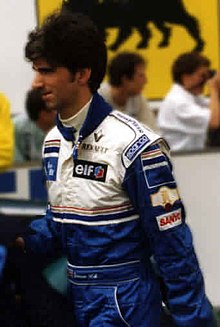

Hill in 2008 | |

| Born | 17 September 1960 |

|---|---|

| Formula One World Championship career | |

| Nationality | British |

| Active years | 1992–1999 |

| Teams | Brabham, Williams, Arrows, Jordan |

| Entries | 122 (115 starts) |

| Championships | 1 (1996) |

| Wins | 22 |

| Podiums | 42 |

| Career points | 360 |

| Pole positions | 20 |

| Fastest laps | 19 |

| First entry | 1992 Spanish Grand Prix |

| First win | 1993 Hungarian Grand Prix |

| Last win | 1998 Belgian Grand Prix |

| Last entry | 1999 Japanese Grand Prix |

Damon Graham Devereux Hill OBE (born 17 September 1960) is a retired British racing driver. In 1996 Hill won the Formula One World Championship. As the son of the late Graham Hill, he is the only son of a world champion to win the title. His father died in an aeroplane crash when Hill was 15, leaving the family in reduced circumstances, and Hill came to professional motorsport at the relatively late age of 23 via racing motorcycles. After some minor success, he moved on to single-seater racing cars and progressed steadily up the ranks to the International Formula 3000 championship by 1989, where, although often competitive, he never won a race.

Hill became a test driver for the Formula One title-winning Williams team in 1992. He was unexpectedly promoted to the Williams race team the following year after Riccardo Patrese's departure and took the first of his 22 victories at the 1993 Hungarian Grand Prix. During the mid 1990s, Hill was Michael Schumacher's main rival for the Formula One Drivers' Championship. The two clashed on and off the track. Their collision at the 1994 Australian Grand Prix gave Schumacher his first title by a single point. Hill became champion two years later but was dropped by Williams for the following season. He went on to drive for the less competitive Arrows and Jordan teams, and in 1998 gave Jordan its first win.

Hill retired from racing after the 1999 season. He has since launched several businesses and has made appearances playing the guitar with celebrity bands. In 2006, he became president of the British Racing Drivers' Club, succeeding Jackie Stewart. He announced in June 2011 that he is to step down from the position on 25 August 2011. He presided over the securing of a 17-year contract for Silverstone to hold Formula One races, which enabled the circuit to see extensive renovation work.

Personal and early life

Hill was born in Hampstead, London on 17 September 1960 to Graham and Bette Hill. Graham Hill was a racing driver in the international Formula One series. He won the world drivers' championship in 1962 and 1968 and became a well known personality in the United Kingdom. Graham Hill's career provided a comfortable living. By 1975 the family lived in a "25-room country mansion" in Hertfordshire and Damon attended the independent Haberdashers' Aske's Boys' School.[1] The death of his father in an aeroplane crash in 1975 left the 15-year-old Hill, his mother, and sisters Samantha and Brigitte in drastically reduced circumstances.[2] Hill worked as a labourer and a motorcycle courier to support his further education.[3]

Hill is married to Susan George ('Georgie' – born 29 April 1961) and they have four children: Oliver (born 4 March 1989), Joshua (born 9 January 1991), Tabitha (born 19 July 1995) and Rosie (born 1 February 1998). Oliver was born with Down's syndrome and Hill and Georgie are both patrons of the Down's Syndrome Association.[4] In 2008, Damon also became the first patron of St. Joseph's Specialist School and College, a school for children with severe learning disabilities and autism in Cranleigh, Surrey. Joshua started racing in 2008,[5] and as of 2011 is competing in the British Formula Renault Championship.[6]

Career

Pre-Formula One

Hill started his motorsport career in motorcycle racing in 1981. He used the same simple, easily identifiable helmet design as his father: eight white oar blades arranged vertically around the upper surface of a dark blue helmet. The device and colours represent the London Rowing Club for which Graham Hill rowed in the early 1950s.[7] Although he won a 350 cc clubman's championship at the Brands Hatch circuit,[8] his racing budget came from working as a building labourer and he "didn't really look destined for great things" according to Motorcycle News reporter Rob McDonnell.[9] His mother, who was concerned about the dangers of racing motorcycles, persuaded him to take a racing car course at the Winfield Racing School in France in 1983. Although he showed "above-average aptitude",[9] Hill had only sporadic single-seater races until the end of 1984. He graduated through British Formula Ford, winning six races driving a Van Diemen for Manadient Racing in 1985, his first full season in cars, and finishing third and fifth in the two UK national championships. He also took third place in the final of the 1985 Formula Ford Festival, helping the UK to win the team prize.[10]

For 1986, Hill planned to move up to the British Formula Three Championship with title-winning team West Surrey Racing. The loss of sponsorship from Ricoh, and then the death of his proposed team-mate Bertrand Fabi in a testing accident, ended Hill's proposed drive. Hill says "When Bert was killed, I took the conscious decision that I wasn't going to stop doing that sort of thing. It's not just competing, it's doing something more exciting. I'm at my fullest skiing, racing or whatever. And I'm more frightened of letting it all slip and reaching 60 and finding I've done nothing."[11] Hill borrowed £100,000 to finance his racing and had a steady first season for Murray Taylor Racing in 1986 before taking a brace of wins in each of the following years for Intersport. He finished third in the 1988 championship.[12]

In Europe in the 1990s, a successful driver would usually progress from Formula Three either directly to Formula One, the pinnacle of the sport, or to the International Formula 3000 championship. However, Hill did not have enough sponsorship available to fund a drive in F3000. He says "I ended up having to reappraise my career a bit. The first thing was to realise how lucky I was to be driving anything. I made the decision that whatever I drove I would do it to the best of my ability and see where it led."[13] He took a one-off drive in the lower level British F3000 championship and shared a Porsche 962 at Le Mans for Richard Lloyd Racing, where the engine failed after 228 laps.[14] He also competed in one race in the British Touring Car Championship at Donington Park, driving a Ford Sierra RS500.[15] Midway through the season, an opportunity arose at the uncompetitive Mooncraft F3000 team. The team tested Hill and Perry McCarthy. Their performances were comparable but according to the team manager, John Wickham, the team sponsors preferred the Hill name.[16] Although his best result was a 15th place, Hill's race performances for Mooncraft led to an offer to drive a Lola chassis for Middlebridge Racing in 1990. He took three pole positions and led five races in 1990, but did not win a race during his Formula 3000 career.[13]

Formula One

1992: Brabham

Hill started his Grand Prix career during the 1991 season as a test driver with the championship-winning Williams team while still competing in the F3000 series.[17] However, midway through 1992 Hill broke into Grand Prix racing as a driver with the struggling Brabham team. The formerly competitive team was in serious financial difficulties. Hill started the season only after three races, replacing Giovanna Amati after her sponsorship had failed to materialise.[18] Amati had not been able to get the car through qualifying but Hill matched his team-mate, Eric van de Poele by qualifying for two races, the mid-season British and Hungarian Grands Prix. Hill continued to test for the Williams team that year and the British Grand Prix saw Nigel Mansell win the race for Williams, while he finished last in the Brabham.[19] The Brabham team collapsed after the Hungarian Grand Prix and did not complete the season.[20]

1993–1996: Williams

When Mansell's team-mate Riccardo Patrese left Williams to drive for Benetton in 1993, Hill was unexpectedly promoted to the race team alongside triple world champion Alain Prost ahead of more experienced candidates such as Martin Brundle and Mika Häkkinen.[21] Traditionally, the reigning driver's world champion carries the number '1' on his car and his team-mate takes the number '2'. Because Mansell, the 1992 champion, was not racing in Formula One in 1993, his Williams team were given numbers '0' and '2'. As the junior partner to Prost, Hill took '0', the second man in Formula One history to do so, after Jody Scheckter in 1973.[22]

The season did not start well when Hill spun out of second place shortly after the start of the South African Grand Prix and failed to finish the race after colliding with Alex Zanardi on lap 16. However, at the Brazilian and European Grands Prix, Prost fared poorly in the rain and Hill drove well enough to finish second behind another triple world champion, Ayrton Senna. In his first full season, Hill benefited from the experience of his veteran French team-mate.[23] His results continued to improve as the season went on. He took pole at the French Grand Prix and closely followed Prost, team orders preventing him from seriously challenging for the win.[24] He suffered an engine failure while leading the British Grand Prix and a puncture near the end of the German Grand Prix also while leading. Hill went on to win three successive races at the Hungarian, Belgian and Italian Grands Prix. In doing so he became the first son of a Formula One Grand Prix winner to take victory himself.[25] Hill's third consecutive win clinched the constructors' championship for Williams and moved him temporarily to second in the drivers' standings until McLaren's Ayrton Senna passed him by winning the last two races. Prost finished the season as champion.

In 1994, Senna joined Hill at Williams. As the reigning champion, this time Prost, was again no longer racing, Hill retained his number '0'. The pre-season betting was that Senna would coast to the title,[26] but with the banning of electronic driver aids, the Benetton team and Michael Schumacher initially proved more competitive and won the first three races. At the San Marino Grand Prix on 1 May, Senna died after his car went off the road. With the team undergoing investigation from the Italian authorities on manslaughter charges, Hill found himself team leader with only one season’s experience in the top flight. It was widely reported at the time that the Williams car's steering column had failed, though Hill told BBC Sport in 2004 that he believed Senna simply took the corner too fast for the conditions, referring to the fact that the car had just restarted the race with cold tyres after being slowed down by a safety car.[27]

Hill represented Williams alone at the next race, the Monaco Grand Prix. His race ended early in a collision involving several cars on the opening lap of the race. For the following race, the Spanish Grand Prix, Williams' test driver David Coulthard was promoted to the race team alongside Hill, who won the race just four weeks after Senna's death. Twenty-six years earlier Graham Hill had won in Spain under similar circumstances for Lotus after the death of his team-mate Jim Clark.[28] Championship leader Schumacher finished second with a gearbox fault restricting him to fifth gear, having led the early laps.

Schumacher led by 66 points to 29 by the mid-point of the season. At the French Grand Prix, Frank Williams brought back Mansell, who shared the second car with Coulthard for the remainder of the season. Mansell earned approximately £900,000 for each of his four races, while Hill was paid £300,000 for the entire season, though Hill's position as lead driver remained unquestioned.[29] Hill came back into contention for the title after winning the British Grand Prix, a race which his father had never won.[30] Schumacher was disqualified from that race and banned for two further races for overtaking Hill during the formation lap and ignoring the subsequent black flag.[31] Four more victories for Hill, three of which were in races where Schumacher was excluded or disqualified, took the title battle to the final event at Adelaide. At Schumacher's first race since his ban, the European Grand Prix, he suggested that Hill (who was eight years his senior) was not a world class driver. However, during the penultimate race at the Japanese Grand Prix, Hill took victory ahead of Schumacher in a rain-soaked event. This put Hill just one point behind the German before the last race of the season.[32]

Neither Hill nor Schumacher finished the season-closing Australian Grand Prix, after a controversial collision which gave the title to Schumacher. Schumacher ran off the track hitting the wall with the right-hand side of his Benetton while leading.[33] Coming into the sixth corner Hill moved to pass the Benetton and the two collided, breaking the Williams' front left suspension wishbone, and forcing both drivers' retirement from the race.[34] BBC Formula One commentator Murray Walker, a great fan and friend of Hill, has often maintained that Schumacher did not cause the crash intentionally.[30][35] WilliamsF1 co-owner Patrick Head feels differently. In 2006 he said that at the time of the incident "Williams were already 100% certain that Michael was guilty of foul play" but did not protest Schumacher's title because the team was still dealing with the death of Ayrton Senna.[36] In 2007, Hill explicitly accused Schumacher of causing the collision deliberately.[37]

Hill's season earned him the 1994 BBC Sports Personality of the Year.[38]

Coming into the 1995 season, Hill was one of the title favourites.[39] The Williams team were reigning constructors' champions, having beaten Benetton in 1994, and with young David Coulthard, who was embarking on his first full season in Formula One, as team-mate, Hill was the clear number one driver. The year started badly when he spun off in Brazil due to a mechanical problem,[40] but wins in the next two races put him in the championship lead. However, Schumacher won seven of the next twelve races, and took his second title with two races to spare, while Benetton took the constructors' championship. Schumacher and Hill had several on-track incidents during the season, two of which led to suspended one race bans. Schumacher's penalty was for blocking and forcing Hill off the road at the Belgian Grand Prix;[41] Hill's was for colliding with Schumacher under braking at the Italian Grand Prix.[42] Hill's season finished positively when he won the Australian Grand Prix by finishing two laps ahead of the runner-up, Olivier Panis in a Ligier.[39]

1995 was a disappointing season for Hill: some of the Williams team had been frustrated with his performances and Frank Williams began to consider bringing in Heinz-Harald Frentzen to replace him. With Hill already under contract for 1996, his place at the team was secure for one more season, but it would prove to be his last at Williams.[39]

In 1996 the Williams car was clearly the quickest in Formula One[43] and Hill went on to win the title ahead of his rookie teammate Jacques Villeneuve, becoming the only son of a Formula One champion to win the championship himself.[44] Taking eight wins and never qualifying off the front row, Hill enjoyed by far his most successful season. At Monaco, where his father had won five times in the 1960s, he led until his engine failed, curtailing his race and allowing Olivier Panis to take his only Formula One win. Near the end of the season, Villeneuve began to mount a title challenge and took pole in the Japanese Grand Prix, the final race of the year. However, Hill took the lead at the start and won both the race and the championship after the Canadian retired.[45]

Starting from the front row in every race of the season, he equaled Ayrton Senna and Alain Prost with their record, as well as for 'most starts from front row in a season'. In 2011, Sebastian Vettel also started from the front row 16 times, although he did not start from front row in all of the races.

Despite winning the title, Hill learned before the season's close that he was to be dropped by Williams in favour of Frentzen for the following season.[44] Hill left Williams as the team's second most successful driver in terms of race victories, with 21, second only to Mansell.[46] Hill's 1996 world championship earned him his second BBC Sports Personality Of The Year Award, making him one of only three people to receive the award twice – the others being boxer Henry Cooper and Mansell.[47] Hill was also awarded the Segrave Trophy by the Royal Automobile Club. The trophy is awarded to the British national who accomplishes the most outstanding demonstration of the possibilities of transport by land, sea, air, or water.[48]

1997: Arrows

As world champion, Hill was in high demand, and had offers to drive from McLaren, Benetton and Ferrari. However, in Hill's opinion neither fully financially valued his World Champion status.[37] Instead, he signed for Arrows, a team which had never won a race in its 20-year history and had scored only a single point the previous year. His title defence in 1997 proved unsuccessful, getting off to a poor start when he only narrowly qualified for the Australian Grand Prix, and then retired on the parade lap. The Arrows car, using tyres from series debutant Bridgestone and engines from previously unsuccessful Yamaha, was generally uncompetitive, and Hill did not score his first point for the team until the British Grand Prix at Silverstone in July. The highlight of the year came at the Hungarian Grand Prix. On a day when the Bridgestone tyres had a competitive edge over their Goodyear rivals, Hill qualified third in a car which had not previously placed higher than 9th on the grid. During the race he passed championship contender Michael Schumacher on the track and was leading late in the race, well ahead of the eventual 1997 World Champion Villeneuve, when a hydraulic problem drastically slowed the Arrows.[49] Villeneuve passed Hill, who finished second and achieved the team's first podium since the 1995 Australian Grand Prix.

1998–1999: Jordan

Hill left Arrows after one season and after coming close to signing for the Prost team run by his former team-mate, decided instead to sign for the Jordan team for the 1998 season.[50] His driving partner there was Ralf Schumacher, the younger brother of Michael. In the first half of the season the car was off the pace and unreliable.[51] At the Canadian Grand Prix however, things began to improve. Hill moved up to second place as others retired or pitted for fuel. On lap 38, Schumacher, delayed by a stop-and-go penalty for forcing Frentzen's Williams off the track, caught Hill on the home straight; Hill moved across the track three times to block Schumacher, who missed his braking point and ran over the kerbs at the chicane to take the place. Hill was running fourth after his only pit stop when he retired with an electrical failure. After the race Schumacher accused Hill of dangerous driving. Hill responded that Schumacher "cannot claim anyone drives badly when you look at the things he's been up to in his career. He took Frentzen out completely."[50] At the German Grand Prix Hill scored his first point of the year, and at the Belgian Grand Prix in very wet conditions he took Jordan's first win. Hill was leading late in the race, with teammate Schumacher closing rapidly, when he suggested that team principal Eddie Jordan tell Schumacher to hold position, instead of risking losing a 1–2 finish. Jordan followed the suggestion, ordering Schumacher not to overtake.[52] Only eight drivers finished the race.[53] The victory was his first since being dropped by the Williams team, which won no races that season. Hill finished the year with a last lap move on Frentzen at the Japanese Grand Prix which earned him fourth place in the race, and Jordan fourth in the constructors' championship.[54]

Hopes were high for 1999, but Hill did not enjoy a good season. Struggling with the new four-grooved tyres introduced that year, he was outpaced by his new team-mate—Heinz-Harald Frentzen, his replacement at Williams two years previously—and appeared to lose motivation.[44][55] After a crash at the Canadian Grand Prix he announced plans to retire from the sport at the end of the year, but after failing to finish the French Grand Prix, which Frentzen won, he considered quitting immediately.[56]

Jordan persuaded Hill to stay on for the British Grand Prix. Going into the weekend, Hill announced he would retire after the race, so Jordan had Jos Verstappen test their car ready to replace Hill should the need arise.[57] Following a strong fifth place at his home event, Hill changed his mind, and decided to see out the year.[58] His best result for the remainder of the season was sixth place, which he achieved in both Hungary and Belgium. With three races of 1999 to go, there were rumours that the Prost team would release Jarno Trulli, who had signed for Jordan for 2000, early to replace Hill, but the Briton completed the season.[59] Meanwhile, his team-mate Frentzen was a title contender going into the final few races, and eventually finished third in the championship. Hill and Frentzen helped Jordan to its best-ever finish of third in the constructors' championship. At the Japanese Grand Prix, Hill's last race in Formula One ended when he spun off the track and pulled into the pits to retire a healthy car.[60]

After racing

In retirement Hill has continued to be involved with cars and motorsport. He founded the Prestige and Super Car Private Members Club P1 International with Michael Breen in 2000;[61] Breen bought Hill out in October 2006. Hill also became involved in a BMW dealership, just outside Royal Leamington Spa, that bore his name and an Audi dealership in Exeter. In April 2006, Hill succeeded Jackie Stewart as President of the British Racing Drivers' Club (BRDC).[62]

In 2009 he received an Honorary Fellowship from the University of Northampton recognising his successful career and his connection with Northampton through Silverstone and the BRDC.[63]

Hill has also regularly appeared in the British media. He has contributed many articles to F1 Racing magazine and has twice appeared in ITV F1's commentary box, covering for Martin Brundle at the 2007 and 2008 Hungarian Grands Prix. Hill also made a UK television advert with F1 commentator Murray Walker for Pizza Hut, in which Walker commentated on Hill's meal as if it were a race.[64] Hill has also appeared on many British television programmes, including Top Gear, This is Your Life, TFI Friday, Shooting Stars and Bang Bang, It's Reeves and Mortimer.[65]

Hill has raced both cars and motorcycles at the Goodwood Festival of Speed[66] and in 2005 he tested the new GP2 Series car. Hill was back behind the wheel of a single-seater race car in the summer of 2006, when he took a 600 bhp (450 kW) Grand Prix Masters machine for a test run around the Silverstone circuit. Hill said that he enjoyed the experience and "I wouldn’t rule [a return to racing] out, but I can’t honestly say that right now I need to race. That is the bit that is missing. I love driving, I love pushing the limit and all the rest of it but racing for me…I don’t have an ambition to do it and I think that’s an important part of the equation."[67]

Music career

Hill was interested in music from an early age and formed the punk band "Sex, Hitler and the Hormones" with some friends while at school. After achieving success in Formula One, he was able to play guitar with several famous musicians, including his friend George Harrison, and appeared on "Demolition Man", the opening track of Def Leppard's album Euphoria. Hill also made a regular appearance at the British Grand Prix alongside other Formula One musicians such as Eddie Jordan. After his retirement at the end of the 1999 season, Hill devoted more time to music and played with celebrity bands including Spike Edney's SAS band,[68] and Pat Cash's Wild Colonial Boys.[69] Hill also formed his own band, The Conrods, which was active between 1999 and 2003 and played cover versions of well known songs from The Rolling Stones, The Beatles and The Kinks. Since becoming president of the BRDC in 2006, Hill says he has abandoned the guitar, being "too busy doing school runs and looking after pets."[70]

Complete International Formula 3000 results

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)

| Year | Entrant | Chassis | Engine | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | DC | Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | GA Motorsports | Lola T88/50 | Ford Cosworth | JER |

VAL |

PAU |

SIL |

MNZ |

PER |

BRH |

BIR |

BUG |

ZOL Ret |

DIJ 8 |

– | 0 |

| 1989 | Footwork | Mooncraft/89 | Mugen Honda | SIL |

VAL |

PAU |

JER |

PER Ret |

BRH Ret |

BIR DNS |

SPA 14 |

BUG 16 |

DIJ 15 |

– | 0 | |

| 1990 | Middlebridge Racing | Lola T90/50 | Ford Cosworth | DON DNQ |

SIL Ret |

PAU Ret |

JER 7 |

MNZ 11 |

PER Ret |

HOC Ret |

BRH 2 |

BIR Ret |

BUG Ret |

NOG 10 |

13th | 6 |

| 1991 | Jordan Racing | Lola T91/50 | Ford Cosworth | VAL 4 |

PAU Ret |

JER 8 |

MUG Ret |

PER 11 |

HOC Ret |

BRH 6 |

SPA Ret |

BUG 4 |

NOG 3 |

7th | 11 |

Complete Formula One results

(key) (Races in bold indicate pole position) (Races in italics indicate fastest lap)[71]

References

- ^ "HILL, Damon Graham Devereux". Who's Who 2008. Oxford University Press. 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. pp. 10–12 & 16–17. ISBN 1-85260-484-0. (subscription required)

- ^ Aspel, Michael (presenter) (-1999-01-11). This Is Your Life – Damon Hill OBE (Television Production). London, UK: British Broadcasting Corporation. Event occurs at 00:56–01:03.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Down's Syndrome Association Annual Report 2006-2007 (PDF). p. 20. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- ^ The Sun, 2008-11-03, p.52

- ^ "Josh Hill Racing". Josh Hill Racing. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill: From Zero to Hero. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Walker, Murray (2001). Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes. Virgin Books. p. 136. ISBN 1-85227-918-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 32. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. pp. 29–36. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: P. Stephens. pp. 37–40. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: P. Stephens. pp. 41–46. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ a b Saward, Joe (1 April 1992). "Interview: Damon Hill". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: P. Stephens. p. 54. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ "BTCC Drivers/Damon Hill". BTCC.net. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: P. Stephens. p. 58. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ "Damon Hill". Atlas F1. 1999. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ "Giovanna Amati – Biography". Formula One Rejects. 6 May 2001. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Donaldson, Gerald. "F1 Hall of Fame – Damon Hill". Formula1.com. Formula One Administration. Archived from the original on 29 November 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: P. Stephens. pp. 96–97. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Walker, Murray (2001). Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes. Virgin Books. p. 25. ISBN 1-85227-918-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Car Number: Car 0". ChicaneF1.com. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Allsop, Derick (1994). Designs on Victory: On the Grand Prix Trail With Benetton. Hutchinson. p. 188. ISBN 0-09-178311-9.

- ^ Saward, Joe (1 August 1993). "Is Alain Prost slowing down?". GrandPrix.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2008. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ^ Henry, Alan (1994). Damon Hill. Cambridge: Patrick Stephens Ltd. p. 8. ISBN 1-85260-484-0.

- ^ Formula One History: After Tamburello F1-GrandPrix.com/History. Retrieved 13 June 2006

- ^ "Hill: Senna was at fault". BBC Sport. British Broadcasting Corporation. 20 April 2004. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 20 October 2007 suggested (help) - ^ "The Spanish Grand Prix – a history". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ Hamilton, Maurice (1998). Frank Williams. London, UK: Macmillan Publishers Ltd. p. 244. ISBN 0-333-71716-3.

- ^ a b Walker, Murray (2001). Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes. Virgin Books. p. 138. ISBN 1-85227-918-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Rendall, Ivan (1993). The Chequered Flag: 100 Years of Motor Racing. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 354. ISBN 0-297-83550-5.

- ^ Horton, Roger. "Reflections on a Racing Rivalry". AtlasF1.com. Haymarket Group. Retrieved 11 October 2008.

- ^ Benson, Andrew (28 May 2006). "Schumacher's chequered history". BBC Sport Online. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2 October 2006.

- ^ "Grand Prix results: Australian GP, 1994". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ Walker, Murray (2002). My Autobiography: Unless I'm Very Much Mistaken. HarperCollins Publishers London. p. 316. ISBN 0-00-712696-4.

- ^ "'Ruthless' Schumi blasted". Motoring.iAfrica.com. 19 July 2006. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ a b Taylor, S (2007). "Lunch with... Damon Hill". Motor Sport. LXXXIII/1: 38.

- ^ "BBC Sports Personality past winners: 1993–1997". BBC Sport Online. British Broadcasting Corporation. 27 November 2003. Retrieved 15 October 2008.

- ^ a b c "Drivers:Damon Hill". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- ^ "Grand Prix results: Brazilian GP, 1995". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Grand Prix Results: Belgian Grand Prix, 1995". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ "Grand Prix results: Italian GP, 1995". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ Saward, Joe (2 December 2006). "Review of Year 1996". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 June 2006.

- ^ a b c Walker, Murray (2001). Murray Walker's Formula One Heroes. Virgin Books. p. 139. ISBN 1-85227-918-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Grand Prix results: Japanese GP, 1996". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "F1 statistics – Williams – wins". Crash Media Group Ltd. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "BBC Sports Personality: Did you know?". BBC Sport Online. British Broadcasting Corporation. 19 November 2004. Retrieved 9 June 2006.

- ^ "Segrave Trophy". The Royal Automobile Club. Retrieved 6 November 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "Race Summaries: 1997". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 5 March 1998. Retrieved 12 June 2006.

- ^ a b Nicholson, Jon (1999). Against the Odds. Macmillan U.K. pp. 115–1167. ISBN 0-333-73655-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nicholson, Jon (1999). Against the Odds. Macmillan U.K. p. 51. ISBN 0-333-73655-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z0pfw5MWbSw

- ^ "Grand Prix results: Belgian GP, 1998". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 14 November 2008.

- ^ "Grand Prix results: Japanese GP, 1998". Grandprix.com. Inside F1, Inc. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- ^ Walker, Murray (2002). My Autobiography: Unless I'm Very Much Mistaken. HarperCollins Publishers London. p. 303. ISBN 0-00-712696-4.

- ^ "Final fling for Damon at Silverstone". Autosport.com. 30 June 1999.

- ^ Henry, Alan (30 June 1999). "Verstappen tries Hill's car for size". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. p. 28.

- ^ "Hill to go on racing". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 19 July 1999. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ "Verstappen to replace Hill?". GrandPrix.com. Inside F1, Inc. 28 June 1999. Retrieved 7 November 2008.

- ^ Matts, Ray (1 November 1999). "No final glory as Hill grinds to a halt". Daily Mail. Associated Newspapers Ltd.

Hill:I retired from the race as I decided that I was so far down the field, there was little point in me carrying on.

- ^ Burrell, Ian (21 November 2005). "Damon Hill: Formula for success". The Independent. Independent News and Media Limited. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- ^ "Stewart set to hand over to Hill". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 3 April 2006. Retrieved 7 June 2006.

- ^ "Damon Hill and Rupert Goold receive Honorary awards". The University of Northampton. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2009.

- ^ Aspel, Michael (presenter) (1997). This Is Your Life – Murray Walker (Television Production). London, UK: British Broadcasting Corporation.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Damon Hill > Credits TV.com. Retrieved 6 October 2006

- ^ Court, Ian (25 July 2001). "The Goodwood Revival Meeting". Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd.

- ^ Galloway, James (11 August 2006). "Damon Hill exclusive". ITV. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ "Artists". sasband.com. Retrieved 26 October 2008.

- ^ Robinson, John (14 January 2006). "Notes of surprise". The Guardian. UK: Guardian News and Media Limited. p. 8. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ Deedes, Henry (24 July 2006). "Damon's guitar is put out to rust". The Independent. UK: Independent News and Media Limited. p. 14. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- ^ "Official Formula 1 Website. Archive: Results for 1992–1999 seasons". Formula One Administration Ltd. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

Further reading

- Damon Hill, Damon Hill: Through the eyes of Damon Hill ISBN 0-316-85392-5

- David Tremayne, Damon Hill: World Champion ISBN 0-297-82262-4

- Alan Henry, Damon Hill: From Zero to Hero ISBN 1-85260-517-0

- Mike Baldock, Damon Hill: Clipping the Apex http://members.lycos.co.uk/justbuzzin/DamonHill/damon_main.htm

Template:Link GA Template:Link GA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Use dmy dates from August 2011

- People from Hampstead

- Sportspeople from London

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- BRDC Gold Star winners

- BBC Sports Personality of the Year winners

- Segrave Trophy recipients

- Old Haberdashers

- English racecar drivers

- English Formula One drivers

- Williams Formula One drivers

- Formula One World Drivers' Champions

- Formula Ford drivers

- British Formula Three Championship drivers

- British Formula 3000 Championship drivers

- British Touring Car Championship drivers

- International Formula 3000 drivers

- 24 Hours of Le Mans drivers

- 1960 births

- Living people