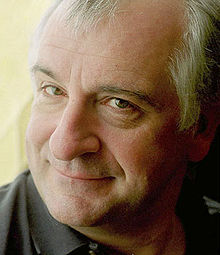

Douglas Adams

Douglas Adams | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Douglas Noel Adams 11 March 1952 Cambridge, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 11 May 2001 (aged 49) Santa Barbara, California, United States |

| Resting place | Highgate Cemetery, London, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | St John's College, Cambridge |

| Genre | Science fiction, comedy, satire |

| Website | |

| douglasadams | |

Douglas Noel Adams (11 March 1952 – 11 May 2001) was an English writer, humorist, and dramatist.

Adams is best known as the author of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which originated in 1978 as a BBC radio comedy before developing into a "trilogy" of five books that sold more than 15 million copies in his lifetime and generated a television series, several stage plays, comics, a computer game, and in 2005 a feature film. Adams's contribution to UK radio is commemorated in The Radio Academy's Hall of Fame.[1]

Adams also wrote Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency (1987) and The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul (1988), and co-wrote The Meaning of Liff (1983), The Deeper Meaning of Liff (1990), Last Chance to See (1990), and three stories for the television series Doctor Who. A posthumous collection of his work, including an unfinished novel, was published as The Salmon of Doubt in 2002.

Adams became known as an advocate for environmentalism and conservation, and also as a lover of fast cars, cameras, technological innovation, and the Apple Macintosh. He was a staunch atheist, imagining a sentient puddle who wakes up one morning and thinks, "This is an interesting world I find myself in—an interesting hole I find myself in—fits me rather neatly, doesn't it? In fact it fits me staggeringly well, must have been made to have me in it!" to demonstrate his view that the fine-tuned Universe argument for God was a fallacy.[2] Biologist Richard Dawkins dedicated his book The God Delusion (2006) to Adams, writing on his death that "Science has lost a friend, literature has lost a luminary, the mountain gorilla and the black rhino have lost a gallant defender."[3]

Early life

Adams was born on 11 March 1952 to Janet (née Donovan; 1927-) and Christopher Douglas Adams (1927-1985) in Cambridge, England.[4] The following year Watson and Crick famously first modelled DNA at Cambridge University, leading Adams to later quip he was DNA in Cambridge months earlier. The family moved to East London a few months after his birth where his sister, Susan, was born three years later.[5] His parents divorced in 1957; Douglas, Susan, and their mother moved to an RSPCA animal shelter in Brentwood, Essex, run by his maternal grandparents.[6]

Education

Adams attended Primrose Hill Primary School in Brentwood. At nine, he passed the entrance exam for Brentwood School, an independent school whose alumni include Robin Day, Jack Straw, Noel Edmonds, and David Irving. Griff Rhys Jones was a year below him, and he was in the same class as Stuckist artist Charles Thomson. He attended the prep school from 1959 to 1964, then the main school until December 1970. His form master, Frank Halford, said of him: "Hundreds of boys have passed through the school but Douglas Adams really stood out from the crowd—literally. He was unnecessarily tall and in his short trousers he looked a trifle self-conscious. "The form-master wouldn't say 'Meet under the clock tower,' or 'Meet under the war memorial'," he joked, "but 'Meet under Adams'."[7][8] Yet it was his ability to write first-class stories that really made him shine."[9]

Adams was six feet tall (1.83 m) by age 12 and stopped growing at 6 ft 5 in (1.96 m). He became the only student ever to be awarded a ten out of ten by Halford for creative writing, something he remembered for the rest of his life, particularly when facing writer's block.[5]

Some of his earliest writing was published at the school, such as a report on its photography club in The Brentwoodian in 1962, or spoof reviews in the school magazine Broadsheet, edited by Paul Neil Milne Johnstone, who later became a character in The Hitchhiker's Guide. He also designed the cover of one issue of the Broadsheet, and had a letter and short story published nationally in The Eagle, the boys' comic, in 1965. A poem entitled "A Dissertation on the task of writing a poem on a candle and an account of some of the difficulties thereto pertaining" written by Adams in January 1970, at the age of 17, was discovered by archivist Stacey Harmer in a cupboard at the school in early 2014. In it, Adams rhymes "futile" with "mute, while" and "exhausted" with "of course did".[10] On the strength of a bravura essay on religious poetry that discussed the Beatles and William Blake, he was awarded an Exhibition in English at St John's College, Cambridge, going up in 1971. He wanted to join the Footlights, an invitation-only student comedy club that has acted as a hothouse for some of the most notable comic talent in England. He was not elected immediately as he had hoped, and started to write and perform in revues with Will Adams (no relation) and Martin Smith, forming a group called "Adams-Smith-Adams," but managed to become a member of the Footlights by 1973.[11] Despite doing very little work—he recalled having completed three essays in three years—he graduated in 1974 with a B.A. in English literature.[4]

Career

Writing

After leaving university Adams moved back to London, determined to break into TV and radio as a writer. An edited version of the Footlights Revue appeared on BBC2 television in 1974. A version of the Revue performed live in London's West End led to Adams being discovered by Monty Python's Graham Chapman. The two formed a brief writing partnership, earning Adams a writing credit in episode 45 of Monty Python for a sketch called "Patient Abuse". He is one of only two people outside the original Python members to get a writing credit (the other being Neil Innes).[12] The sketch plays on the idea of mind-boggling paper work in an emergency, a joke later incorporated into the Vogons' obsession with paperwork. Adams also contributed to a sketch on the album for Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

Adams had two brief appearances in the fourth series of Monty Python's Flying Circus. At the beginning of episode 42, "The Light Entertainment War", Adams is in a surgeon's mask (as Dr. Emile Koning, according to on-screen captions), pulling on gloves, while Michael Palin narrates a sketch that introduces one person after another but never actually gets started. At the beginning of episode 44, "Mr. Neutron", Adams is dressed in a pepper-pot outfit and loads a missile on to a cart driven by Terry Jones, who is calling for scrap metal ("Any old iron..."). The two episodes were broadcast in November 1974. Adams and Chapman also attempted non-Python projects, including Out of the Trees.

At this point Adams's career stalled; his writing style was unsuited to the current style of radio and TV comedy.[4] To make ends meet he took a series of odd jobs, including as a hospital porter, barn builder, and chicken shed cleaner. He was employed as a bodyguard by a Qatari family, who had made their fortune in oil. Anecdotes about the job included that the family had once ordered one of everything from a hotel's menu, tried all the dishes, and sent out for hamburgers. Another story had to do with a prostitute sent to the floor Adams was guarding one evening. They acknowledged each other as she entered, and an hour later, when she left, she is said to have remarked, "At least you can read while you're on the job."[13]

During this time Adams continued to write and submit sketches, though few were accepted. In 1976 his career had a brief improvement when he wrote and performed, to good review, Unpleasantness at Brodie's Close at the Edinburgh Fringe festival. But by Christmas work had dried up again, and a depressed Adams moved to live with his mother.[4] The lack of writing work hit him hard and a low confidence would become a feature of Adams's life; "I have terrible periods of lack of confidence [..] I briefly did therapy, but after a while I realised it was like a farmer complaining about the weather. You can't fix the weather – you just have to get on with it".[14]

Some of Adams's early radio work included sketches for The Burkiss Way in 1977 and The News Huddlines. He also wrote, again with Graham Chapman, the 20 February 1977 episode of Doctor on the Go, a sequel to the Doctor in the House television comedy series. After the first radio series of The Hitchhiker's Guide became successful, Adams was made a BBC radio producer, working on Week Ending and a pantomime called Black Cinderella Two Goes East. He left the position after six months to become the script editor for Doctor Who.

In 1979 Adams and John Lloyd wrote scripts for two half-hour episodes of Doctor Snuggles: "The Remarkable Fidgety River" and "The Great Disappearing Mystery" (episodes seven and twelve). John Lloyd was also co-author of two episodes from the original Hitchhiker radio series ("Fit the Fifth" and "Fit the Sixth", also known as "Episode Five" and "Episode Six"), as well as The Meaning of Liff and The Deeper Meaning of Liff. Lloyd and Adams also collaborated on a science fiction film comedy project based on The Guinness Book of World Records, which would have starred John Cleese as the UN Secretary General, and had a race of aliens beating humans in athletic competitions, but the humans winning in all of the "absurd" record categories. The project never proceeded past a treatment.

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was a concept for a science-fiction comedy radio series pitched by Adams and radio producer Simon Brett to BBC Radio 4 in 1977. Adams came up with an outline for a pilot episode, as well as a few other stories (reprinted in Neil Gaiman's book Don't Panic: The Official Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Companion) that could potentially be used in the series.

According to Adams, the idea for the title occurred to him while he lay drunk in a field in Innsbruck, Austria, gazing at the stars. He was carrying a copy of The Hitchhiker's Guide to Europe, and it occurred to him that "somebody ought to write a Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy". He later said that the constant repetition of this anecdote had obliterated his memory of the actual event.[15]

Despite the original outline, Adams was said to make up the stories as he wrote. He turned to John Lloyd for help with the final two episodes of the first series. Lloyd contributed bits from an unpublished science fiction book of his own, called GiGax.[16] Very little of Lloyd's material survived in later adaptations of Hitchhiker's, such as the novels and the TV series. The TV series itself was based on the first six radio episodes, and sections contributed by Lloyd were largely re-written.

BBC Radio 4 broadcast the first radio series weekly in the UK in March and April 1978. The series was distributed in the United States by National Public Radio. Following the success of the first series, another episode was recorded and broadcast, which was commonly known as the Christmas Episode. A second series of five episodes was broadcast one per night, during the week of 21–25 January 1980.

While working on the radio series (and with simultaneous projects such as The Pirate Planet) Adams developed problems keeping to writing deadlines that only got worse as he published novels. Adams was never a prolific writer and usually had to be forced by others to do any writing. This included being locked in a hotel suite with his editor for three weeks to ensure that So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish was completed.[17] He was quoted as saying, "I love deadlines. I love the whooshing noise they make as they go by."[18] Despite the difficulty with deadlines, Adams wrote five novels in the series, published in 1979, 1980, 1982, 1984, and 1992.

The books formed the basis for other adaptations, such as three-part comic book adaptations for each of the first three books, an interactive text-adventure computer game, and a photo-illustrated edition, published in 1994. This latter edition featured a 42 Puzzle designed by Adams, which was later incorporated into paperback covers of the first four Hitchhiker's novels (the paperback for the fifth re-used the artwork from the hardback edition).[19]

In 1980 Adams also began attempts to turn the first Hitchhiker's novel into a movie, making several trips to Los Angeles, and working with a number of Hollywood studios and potential producers. The next year, the radio series became the basis for a BBC television mini-series[20] broadcast in six parts. When he died in 2001 in California, he had been trying again to get the movie project started with Disney, which had bought the rights in 1998. The screenplay finally got a posthumous re-write by Karey Kirkpatrick, and the resulting movie was released in 2005.

Radio producer Dirk Maggs had consulted with Adams, first in 1993, and later in 1997 and 2000 about creating a third radio series, based on the third novel in the Hitchhiker's series.[21] They also discussed the possibilities of radio adaptations of the final two novels in the five-book "trilogy". As with the movie, this project was only realised after Adams's death. The third series, The Tertiary Phase, was broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in September 2004 and was subsequently released on audio CD. With the aid of a recording of his reading of Life, the Universe and Everything and editing, Adams can be heard playing the part of Agrajag posthumously. So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish and Mostly Harmless made up the fourth and fifth radio series, respectively (on radio they were titled The Quandary Phase and The Quintessential Phase) and these were broadcast in May and June 2005, and also subsequently released on Audio CD. The last episode in the last series (with a new, "more upbeat" ending) concluded with, "The very final episode of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams is affectionately dedicated to its author."[22]

Dirk Gently series

In between Adams's first trip to Madagascar with Mark Carwardine in 1985, and their series of travels that formed the basis for the radio series and non-fiction book Last Chance to See, Adams wrote two other novels with a new cast of characters. Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency was first published in 1987, and was described by its author as "a kind of ghost-horror-detective-time-travel-romantic-comedy-epic, mainly concerned with mud, music and quantum mechanics."[23] It was derived from two Doctor Who serials Adams had written.

A sequel novel, The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul, was published a year later. This was an entirely original work, Adams's first since So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish. After the book tour, Adams set off on his round-the-world excursion which supplied him with the material for Last Chance to See.

Doctor Who

Adams sent the script for the HHGG pilot radio programme to the Doctor Who production office in 1978, and was commissioned to write The Pirate Planet (see below). He had also previously attempted to submit a potential movie script, called "Doctor Who and the Krikkitmen," which later became his novel Life, the Universe and Everything (which in turn became the third Hitchhiker's Guide radio series). Adams then went on to serve as script editor on the show for its seventeenth season in 1979. Altogether, he wrote three Doctor Who serials starring Tom Baker as the Doctor:

- "The Pirate Planet" (the second serial in the "Key To Time" arc, in Season 16)

- "City of Death" (with producer Graham Williams, from an original storyline by writer David Fisher. It was transmitted under the pseudonym "David Agnew")

- "Shada" (only partially filmed; not televised due to production industry disputes)

The episodes authored by Adams are some of the few that have not been novelised as Adams would not allow anyone else to write them, and asked for a higher price than the publishers were willing to pay.[24] "Shada" was later novelised by Gareth Roberts in 2012.

Adams was also known to allow in-jokes from The Hitchhiker's Guide to appear in the Doctor Who stories he wrote and other stories on which he served as Script Editor. Subsequent writers have also inserted Hitchhiker's references, even as recently as 2013. Conversely, at least one reference to Doctor Who was worked into a Hitchhiker's novel. In Life, the Universe and Everything, two characters travel in time and land on the pitch at Lord's Cricket Ground. The reaction of the radio commentators to their sudden appearance is very similar to the reactions of commentators in a scene in the eighth episode of the 1965–66-story The Daleks' Master Plan, which has the Doctor's TARDIS materialise on the pitch at Lord's.

Elements of Shada and City of Death were reused in Adams's later novel Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency, in particular the character of Professor Chronotis. Big Finish Productions eventually remade Shada as an audio play starring Paul McGann as the Doctor. Accompanied by partially animated illustrations, it was webcast on the BBC website in 2003, and subsequently released as a two-CD set later that year. An omnibus edition of this version was broadcast on the digital radio station BBC7 on 10 December 2005.

In the Doctor Who 2012 Christmas episode The Snowmen, writer Steven Moffat was inspired by a storyline that Adams pitched called The Doctor Retires.[25]

When he was at school he wrote and performed a play called Doctor Which.[26]

Music

Adams played the guitar left-handed and had a collection of twenty-four left-handed guitars when he died (having received his first guitar in 1964). He also studied piano in the 1960s with the same teacher as Paul Wickens, the pianist who plays in Paul McCartney's band (and composed the music for the 2004–2005 editions of the Hitchhiker's Guide radio series).[27] Pink Floyd and Procol Harum had important influence on Adams's work.

Pink Floyd

Adams included a reference to Pink Floyd in the original radio version of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, in which he describes the main characters surveying the landscape of an alien planet while Marvin, their android companion, hums Pink Floyd's "Shine on You Crazy Diamond". This was cut out of the CD version. Adams also compared the various noises that the kakapo makes to "Pink Floyd studio out-takes" in his non-fiction book on endangered species, Last Chance to See.

Adams's official biography shares its name with the song "Wish You Were Here" by Pink Floyd. Adams was friends with Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour and, on Adams's 42nd birthday (the number 42 having special significance, being the Answer to the Ultimate Question of Life, the Universe, and Everything), he was invited to make a guest appearance at Pink Floyd's 28 October 1994 concert at Earls Court in London, playing guitar on the songs "Brain Damage" and "Eclipse".[28] Adams chose the name for Pink Floyd's 1994 album, The Division Bell, by picking the words from the lyrics to one of its tracks, "High Hopes".[28] Gilmour also performed at Adams's memorial service in 2001, and what would have been Adams's 60th birthday party in 2012.

Procol Harum

Douglas Adams was a friend of Gary Brooker, the lead singer, pianist and songwriter of Procol Harum. Adams invited Brooker to one of the many parties that Adams held at his house. On one such occasion Gary Brooker performed the full (4 verse) version of "A Whiter Shade of Pale". Brooker also performed at Adams's memorial service.

Adams appeared on stage with Brooker to perform "In Held 'Twas in I" at Redhill when the band's lyricist Keith Reid was not available. On several other occasions he introduced Procol Harum at their gigs.

Adams would listen to music while writing, and this would occasionally influence his work. On one occasion the title track from the Procol Harum album Grand Hotel was playing when

Suddenly in the middle of the song there was this huge orchestral climax that came out of nowhere and did not seem to be about anything. I kept wondering what was this huge thing happening in the background? And I eventually thought ... it sounds as if there ought to be some sort of floorshow going on. Something huge and extraordinary, like, well, like the end of the universe. And so that was where the idea for The Restaurant at the End of the Universe came from.

— Douglas Adams, Procol Harum at The Barbican[29]

Computer games and projects

Douglas Adams created an interactive fiction version of HHGG with Steve Meretzky from Infocom in 1984. In 1986 he participated in a week-long brainstorming session with the Lucasfilm Games team for the game Labyrinth. Later he was also involved in creating Bureaucracy (also by Infocom, but not based on any book; Adams wrote it as a parody of events in his own life).

Adams was a founder-director and Chief Fantasist of The Digital Village, a digital media and Internet company with which he created Starship Titanic, a Codie Award-winning and BAFTA-nominated adventure game, which was published in 1998 by Simon and Schuster.[30][31] Terry Jones wrote the accompanying book, entitled Douglas Adams Starship Titanic, since Adams was too busy with the computer game to do both. In April 1999, Adams initiated the h2g2 collaborative writing project, an experimental attempt at making The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy a reality, and at harnessing the collective brainpower of the internet community. It found a new home at BBC Online in 2001.[30]

In 1990 Adams wrote and presented a television documentary programme Hyperland[32] which featured Tom Baker as a "software agent" (similar to the assistant pictured in Apple's Knowledge Navigator video of future concepts from 1987), and interviews with Ted Nelson, the co-inventor of hypertext and the person who coined the term. Although Adams did not invent hypertext, he was an early adopter and advocate of it. This was the same year that Tim Berners-Lee used the idea of hypertext in his HTML.

Personal beliefs and activism

Atheism and views on religion

Adams described himself as a "radical atheist", adding radical for emphasis so he would not be asked if he meant agnostic. He told American Atheists that this made things easier, but most importantly it conveyed the fact that he really meant it. "I am convinced that there is not a god," he said. Despite this, he remained fascinated by religion because of its effect on human affairs. "I love to keep poking and prodding at it. I've thought about it so much over the years that that fascination is bound to spill over into my writing."[33]

The evolutionary biologist and atheist Richard Dawkins in The God Delusion uses Adams's influence throughout to exemplify arguments for non-belief; Dawkins jokingly states that Adams is "possibly [my] only convert" to atheism.[34] The book is dedicated to Adams, quoting Ford Prefect from The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, "Isn't it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?"

Environmental activism

Adams was also an environmental activist who campaigned on behalf of endangered species. This activism included the production of the non-fiction radio series Last Chance to See, in which he and naturalist Mark Carwardine visited rare species such as the Kakapo and Baiji, and the publication of a tie-in book of the same name. In 1992 this was made into a CD-ROM combination of audio book, e-book and picture slide show.

Adams and Mark Carwardine contributed the 'Meeting a Gorilla' passage from Last Chance to See to the book The Great Ape Project.[35] This book, edited by Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer launched a wider-scale project in 1993, which calls for the extension of moral equality to include all great apes, human and non-human.

In 1994 he participated in a climb of Mount Kilimanjaro while wearing a rhino suit for the British charity organisation Save the Rhino International. Puppeteer William Todd-Jones, who had originally worn the suit in the London Marathon to raise money and bring awareness to the group, also participated in the climb wearing a rhino suit; Adams wore the suit while travelling to the mountain before the climb proper began. About £100,000 were raised through that event, benefiting schools in Kenya and a Black Rhinoceros preservation programme in Tanzania. Adams was also an active supporter of the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund.

In 1998, Adams published an essay bemoaning the wasteful profusion and confusion of power adapters, and calling for more standardisation.[36] In 2009, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) announced support of the Open Mobile Terminal Platform's (OMTP) "Common Charging and Local Data Connectivity" standard which specifies the use of micro-USB receptacles on mobile phones and standard USB receptacles on (common / interchangeable) chargers.[37] The hope is to markedly reduce the profusion of non-interchangeable power adapters needed for each year's new output of mobile phone models.

Since 2003, Save the Rhino has held an annual Douglas Adams Memorial Lecture around the time of his birthday to raise money for environmental campaigns.[38] The lectures in the series are:

- 2003 Richard Dawkins – Queerer than we can suppose: the strangeness of science

- 2004 Robert Swan – Mission Antarctica

- 2005 Mark Carwardine – Last Chance to See... Just a bit more

- 2006 Robert Winston – Is the Human an Endangered Species?

- 2007 Richard Leakey – Wildlife Management in East Africa – Is there a future?

- 2008 Steven Pinker – The Stuff of Thought, Language as a Window into Human Nature

- 2009 Benedict Allen – Unbreakable

- 2010 Marcus du Sautoy – 42: the answer to life, the universe and prime numbers

- 2011 Brian Cox – The Universe and Why We Should Explore It

- 2012 Lecture replaced by "Douglas Adams The Party"[39]

- 2013 Adam Rutherford – Creation: the origin and the future of life[40]

- 2014 Roger Highfield and Simon Singh - The Science of Harry Potter and the Mathematics of The Simpsons[41]

Technology and innovation

Though he did not buy his first word processor until 1982, he had considered one as early as 1979. He was quoted as saying that until 1982, he had difficulties with "the impenetrable barrier of jargon. Words were flying backwards and forwards without concepts riding on their backs." In 1982 his first purchase was a 'Nexus'. In 1983, when he and Jane Belson went out to Los Angeles, he bought a DEC Rainbow. Upon their return to England, Adams bought an Apricot, then a BBC Micro and a Tandy 1000.[42] In Last Chance to See Adams mentions his Cambridge Z88, which he had taken to Zaire on a quest to find the Northern White Rhinoceros.[43]

Adams's posthumously published work, The Salmon of Doubt, features multiple articles by him on the subject of technology, including reprints of articles that originally ran in MacUser magazine, and in The Independent on Sunday newspaper. In these Adams claims that one of the first computers he ever saw was a Commodore PET, and that he has "adored" his Apple Macintosh ("or rather my family of however many Macintoshes it is that I've recklessly accumulated over the years") since he first saw one at Infocom's offices in Boston in 1984.[44]

Adams was a Macintosh user from the time they first came out in 1984 until his death in 2001. He was the first person to buy a Mac in Europe (the second being Stephen Fry – though some accounts differ on this, saying Fry bought his Mac first. Fry claims he was second to Adams[45]). Adams was also an "Apple Master", one of several celebrities whom Apple made into spokespeople for its products (other Apple Masters included John Cleese and Gregory Hines). Adams's contributions included a rock video that he created using the first version of iMovie with footage featuring his daughter Polly. The video was available on Adams's .Mac homepage. Adams installed and started using the first release of Mac OS X in the weeks leading up to his death. His very last post to his own forum was in praise of Mac OS X and the possibilities of its Cocoa programming framework. He said it was "awesome...", which was also the last word he wrote on his site.[46] Adams can also be seen in the Omnibus tribute included with the Region One/NTSC DVD release of the TV adaptation of The Hitchhiker's Guide using Mac OS X on his PowerBook G3.

Adams used e-mail extensively long before it reached popular awareness, using it to correspond with Steve Meretzky during the pair's collaboration on Infocom's version of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.[42] While living in New Mexico in 1993 he set up another e-mail address and began posting to his own USENET newsgroup, alt.fan.douglas-adams, and occasionally, when his computer was acting up, to the comp.sys.mac hierarchy.[47] Many of his posts are now archived through Google. Challenges to the authenticity of his messages later led Adams to set up a message forum on his own website to avoid the issue. In 1996, Adams was a keynote speaker at The Microsoft Professional Developers Conference (PDC) where he described the personal computer as being a modelling device. The video of his keynote speech is archived on Channel 9.[48] Adams was also a keynote speaker for the April 2001 Embedded Systems Conference in San Francisco, one of the major technical conferences on embedded system engineering. In his keynote speech, he shared his vision of technology and how it should contribute in everyday – and every man's – life.[49]

Personal life

Adams moved to Upper Street, Islington, in 1981[50] and to Duncan Terrace in Islington in the late 1980s.[50]

In the early 1980s Adams had an affair with novelist Sally Emerson, who was separated from her husband at that time. Adams later dedicated his book Life, the Universe and Everything to Emerson. In 1981 Emerson returned to her husband, Peter Stothard, a contemporary of Adams's at Brentwood School, and later editor of The Times. Adams was soon introduced by friends to Jane Belson, with whom he later became romantically involved. Belson was the "lady barrister" mentioned in the jacket-flap biography printed in his books during the mid-1980s ("He [Adams] lives in Islington with a lady barrister and an Apple Macintosh"). The two lived in Los Angeles together during 1983 while Adams worked on an early screenplay adaptation of Hitchhiker's. When the deal fell through, they moved to London, and after several separations ("He is currently not certain where he lives, or with whom")[51] and an aborted engagement, they married on 25 November 1991. Adams and Belson had one daughter together, Polly Jane Rocket Adams, born on 22 June 1994, shortly after Adams turned 42. In 1999 the family moved from London to Santa Barbara, California, where they lived until his death. Following the funeral, Jane Belson and Polly Adams returned to London.[52] Jane died on 7 September 2011.[53][54]

Death and legacy

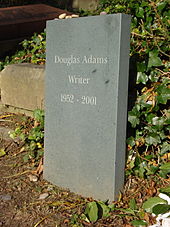

Adams died of a heart attack on 11 May 2001, aged 49, after resting from his regular workout at a private gym in Montecito, California. He had unknowingly suffered a gradual narrowing of the coronary arteries, which led at that moment to a myocardial infarction and a fatal cardiac arrhythmia. Adams had been due to deliver the commencement address at Harvey Mudd College on 13 May.[55] His funeral was held on 16 May in Santa Barbara, California. His remains were subsequently cremated and the ashes placed in Highgate Cemetery in north London in June 2002.[56]

A memorial service was held on 17 September 2001 at St. Martin-in-the-Fields church, Trafalgar Square, London. This became the first church service broadcast live on the web by the BBC.[57] Video clips of the service are still available on the BBC's website for download.[58]

One of his last public appearances was a talk given at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Parrots, the universe and everything, recorded days before his death.[59] A full transcript of the talk is available.[60]

The Minor Planet Centre space agency has named an asteroid Arthurdent, coincidentally announcing its plan the day Adams died.[30] There is also an asteroid named after Adams himself.[61]

In May 2002 The Salmon of Doubt was published, containing many short stories, essays, and letters, as well as eulogies from Richard Dawkins, Stephen Fry (in the UK edition), Christopher Cerf (in the US edition), and Terry Jones (in the US paperback edition). It also includes eleven chapters of his long-awaited but unfinished novel, The Salmon of Doubt, which was originally intended to become a new Dirk Gently novel, but might have later become the sixth Hitchhiker novel.[62][63]

Other events after Adams's death included a webcast production of Shada, allowing the complete story to be told, radio dramatisations of the final three books in the Hitchhiker's series, and the completion of the film adaptation of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. The film, released in 2005, posthumously credits Adams as a producer, and several art design elements – most notably a head-shaped planet seen near the end of the film – incorporated Adams's features.

A 12-part radio series based on the Dirk Gently novels was announced in 2007, with annual transmissions starting in October.[64]

BBC Radio 4 also commissioned a third Dirk Gently radio series based on the incomplete chapters of The Salmon of Doubt, and written by Kim Fuller;[65] however, this was dropped in favour of a BBC TV series based on the two completed novels.[66] A sixth Hitchhiker novel, And Another Thing..., by Artemis Fowl author Eoin Colfer, was released on 12 October 2009 (the 30th anniversary of the first book), published with the full support of Adams's estate. A BBC Radio 4 Book at Bedtime adaptation and an audio book soon followed.

On 25 May 2001, two weeks after Adams's death, his fans organised a tribute known as Towel Day, which has been observed every year since then.

In 2011, over 3000 people took part in a public vote to choose the subjects of People's Plaques in Islington.[50] Adams received 489 votes, and a plaque is due to be erected in his honour.[50]

On 11 March 2013, Adams's 61st birthday was celebrated with an interactive Google Doodle.[67][68]

Works

- Monty Python's Flying Circus Episode 45, Party Political Broadcast on Behalf of the Liberal Party (1972)

- The Private Life of Genghis Khan (1975), based on a comedy sketch Adams co-wrote with Graham Chapman (short story)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1978) (radio series)

- The Pirate Planet, a Doctor Who serial first broadcast in 1978

- Doctor Snuggles, contributed to a children's TV series (1979)

- City of Death, a Doctor Who serial, cowritten with Graham Williams, based on a story by David Fisher, first broadcast October 1979

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979) (novel)

- Shada (1979–1980), a Doctor Who serial

- The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (1980) (novel)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1981) (TV series)

- Life, the Universe and Everything (1982) (novel)

- The Meaning of Liff (1983 (book), with John Lloyd)

- So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (1984) (novel)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1984, with Steve Meretzky) (computer game)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts (1985, with Geoffrey Perkins)

- Young Zaphod Plays It Safe (short story) (1986)

- A Christmas Fairly Story [sic] (1986, with Terry Jones), and

- Supplement to The Meaning of Liff (1986, with John Lloyd and Stephen Fry), both part of

- The Utterly Utterly Merry Comic Relief Christmas Book (1986, edited with Peter Fincham)

- Bureaucracy (1987) (computer game)

- Dirk Gently's Holistic Detective Agency (1987) (novel)

- The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul (1988) (novel)

- Hyperland (TV documentary) (1990)

- The Deeper Meaning of Liff (1990, with John Lloyd)

- Last Chance to See (1990, with Mark Carwardine) (book)

- Mostly Harmless (1992) (novel)

- The Illustrated Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1994)

- Douglas Adams's Starship Titanic (1997), written by Terry Jones, based on an idea by Adams

- Starship Titanic (computer game) (1998)

- h2g2 (internet project) (1999)

- The Internet: The Last Battleground of the 20th century (radio series) (2000)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Future (radio series) (2001) final project for BBC Radio 4 before his death

- Parrots, the universe and everything (2001)

- The Salmon of Doubt (2002), unfinished novel manuscript (11 chapters), short stories, essays, and interviews (also available as an audiobook, read by Simon Jones)

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (2005) (film)

Articles by others

- Herbert, R. (1980). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (Book Review). Library Journal, 105(16), 1882.

- Adams, J., & Brown, R. (1981). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (Book Review). School Library Journal, 27(5), 74.

- Nickerson, S. L. (1982). The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Book). Library Journal, 107(4), 476.

- Nickerson, S. L. (1982). Life, the Universe, and Everything (Book). Library Journal, 107(18), 2007.

- Morner, C. (1982). The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Book Review). School Library Journal, 28(8), 87.

- Morner, C. (1983). Life, the Universe and Everything (Book Review). School Library Journal, 29(6), 93.

- Shorb, B. (1985). So Long, and Thanks for All the Fish (Book). School Library Journal, 31(6), 90.

- The Long Dark Tea-Time of the Soul (Book). (1989). Atlantic (02769077), 263(4), 99.

- Hoffert, B., & Quinn, J. (1990). Last Chance To See (Book). Library Journal, 115(16), 77.

- Reed, S. S., & Cook, I. I. (1991). Dances with kakapos. People, 35(19), 79.

- Last Chance to See (Book). (1991). Science News, 139(8), 126.

- Field, M. M., & Steinberg, S. S. (1991). Douglas Adams. Publishers Weekly, 238(6), 62.

- Dieter, W. (1991). Last Chance to See (Book). Smithsonian, 22(3), 140.

- Dykhuis, R. (1991). Last Chance To See (Book). Library Journal, 116(1), 140.

- Beatty, J. (1991). Good Show (Book). Atlantic (02769077), 267(3), 131.

- A guide to the future. (1992). Maclean's, 106(44), 51.

- Zinsser, J. (1993). Audio reviews: Fiction. Publishers Weekly, 240(9), 24.

- Taylor, B., & Annichiarico, M. (1993). Audio reviews. Library Journal, 118(2), 132.

- Good reads. (1995). NetGuide, 2(4), 109.

- Stone, B. (1998). The unsinkable starship. Newsweek, 131(15), 78.

- Gaslin, G. (2001). Galaxy Quest. Entertainment Weekly, (599), 79.

- So long, and thanks for all the fish. (2001). Economist, 359(8222), 79.

- Geier, T., & Raftery, B. M. (2001). Legacy. Entertainment Weekly, (597), 11.

- Passages. (2001). Maclean's, 114(21), 13.

- Don't panic! Douglas Adams to keynote Embedded show. (2001). Embedded Systems Programming, 14(3), 10.

- Ehrenman, G. (2001). World Wide Weird. InternetWeek, (862), 15.

- Zaleski, J. (2002). The Salmon of Doubt (Book). Publishers Weekly, 249(15), 43.

- Mort, J. (2002). The Salmon of Doubt (Book). Booklist, 98(16), 1386.

- Lewis, D. L. (2002). Last Time Round The Galaxy. Quadrant Magazine, 46(9), 84.

- Burns, A. (2002). The Salmon of Doubt (Book). Library Journal, 127(15), 111.

- Burns, A., & Rhodes, B. (2002). The Restaurant at the End of the Universe (Book). Library Journal, 127(19), 118.

- Kaveney, R. (2002). A cheerful whale. TLS, (5173), 23.

- Pearl, N., & Welch, R. (2003). The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy (Book). Library Journal, 128(11), 124.

- Preying on composite materials. (2003). R&D Magazine, 45(6), 44.

- Webb, N. (2003). The Berkeley Hotel hostage. Bookseller, (5069), 25.

- The author who toured the universe. (2003). Bookseller, (5060), 35.

- Osmond, A. (2005). Only human. Sight & Sound, 15(5), 12–15.

- Culture vulture. (2005). Times Educational Supplement, (4640), 19.

- Maughan, S. (2005). Audio Bestsellers/Fiction. Publishers Weekly, 252(30), 17.

- Hitchhiker At The Science Museum. (2005). In Britain, 14(10), 9.

- Rea, A. (2005). The Adams asteroids. New Scientist, 185(2488), 31.

- Most Improbable Adventure. (2005). Popular Mechanics, 182(5), 32.

- The Hitchhiker's Guide To The Galaxy: The Tertiary Phase. (2005). Publishers Weekly, 252(14), 21.

- Bartelt, K. R. (2005). Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams. Library Journal, 130(4), 86.

- Larsen, D. (2005). I was a teenage android. New Zealand Listener, 198(3390), 37–38.

- Tanner, J. C. (2005). Simplicity: it's hard. Telecom Asia, 16(6), 6.

- Nielsen Bookscan Charts. (2005). Bookseller, (5175), 18–21.

- Buena Vista launches regional site to push Hitchhiker's movie. (2005). New Media Age, 9.

- Shynola bring Beckland to life. (2005). Creative Review, 25(3), 24–26.

- Carwardine, M. (15 September 2007). The baiji: So long and thanks for all the fish. New Scientist. pp. 50–53.

- Czarniawska, B. (2008). Accounting and gender across times and places: An excursion into fiction. Accounting, Organizations & Society, 33(1), 33–47.

- Pope, M. (2008). Life, the Universe, Religion and Science. Issues, (82), 31–34.

- Bearne, S. (2008). BBC builds site to trail Last Chance To See TV series. New Media Age, 08.

- Arrow to reissue Adams. (2008). Bookseller, (5352), 14.

- Page, B. (2008). Colfer is new Hitchhiker. Bookseller, (5350), 7.

- I've got a perfect puzzle for you. (2009). Bookseller, (5404), 42.

- Mostly Harmless.... (2009). Bookseller, (5374), 46.

- Penguin and PanMac hitch a ride together. (2009). Bookseller, (5373), 6.

- Adams, Douglas. Britannica Biographies [serial online]. October 2010;:1

- Douglas (Noël) Adams (1952–2001). Hutchinson's Biography Database [serial online]. July 2011;:1

- My life in books. (2011). Times Educational Supplement, (4940), 27.

Notes

- ^ "The Radio Academy Hall of Fame". The Radio Academy. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Adams 1998; Dawkins 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (13 May 2001). "Lament for Douglas Adams". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d Webb 2005b

- ^ a b Adams 2002, pp. xix

- ^ Webb 2005a, p. 32.

- ^ Adams 2002, pp. 7

- ^ Botti, Nicholas. "Interview with Frank Halford". Life, DNA, and H2G2. 2009. Web. Retrieved 13 March 2012. (Click on link at bottom for facsimile page from Daily News article, 7 March 1998.)

- ^ Simpson 2003, pp. 9

- ^ Flood, Alison (March 2014). "Lost poems of Douglas Adams and Griff Rhys Jones found in school cupboard", The Guardian, 19 March 2014. Accessed 2 July 2014

- ^ Simpson 2003, pp. 30–40

- ^ "Terry Jones remembers Douglas Adams, 'the last of the Pythons'". The Times. 10 October 2009.

- ^ Webb 2005a, p. 93.

- ^ Adams 2002, pp. prologue

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2003). Geoffrey Perkins (ed.), Additional Material by M. J. Simpson (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: The Original Radio Scripts (25th Anniversary Edition ed.). Pan Books. p. 10. ISBN 0-330-41957-9.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ Webb 2005a, p. 120.

- ^ Felch 2004

- ^ Simpson 2003, pp. 236

- ^ Internet Book List page, with links to all five novels, and reproductions of the 1990s paperback covers that included the 42 Puzzle.

- ^ The Hitch Hiker's Guide to the Galaxy, Internet Movie Database

- ^ Adams, Douglas. (2005). Dirk Maggs, dramatisations and editor (ed.). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy Radio Scripts: The Tertiary, Quandary and Quintessential Phases. Pan Books. xiv. ISBN 0-330-43510-8.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Adams, Dirk Maggs, Page 356.

- ^ Gaiman, Neil (2003). Don't Panic: Douglas Adams & The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (Second U.S. edition ed.). Titan Books. p. 169. ISBN 1-84023-742-2.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "A 1990s Doctor Who FAQ". Skepticfiles.org. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ Moffat, Steven (24 December 2012). "Doctor Who Christmas special: Steven Moffat, Matt Smith and Jenna-Louise Coleman reveal all". Radio Times. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- ^ Adams 2002, pp. xx

- ^ Webb, page 49.

- ^ a b Mabbett, Andy (2010). Pink Floyd — The Music and the Mystery. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84938-370-7.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (8 February 1996). "Text of one of Douglas Adams's introductions of Procol Harum in concert". Retrieved 21 August 2006.

- ^ a b c BBC Online (no date) "The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy: DNA (1952-2001)" Accessed 9 July 2014

- ^ Botti, Nicolas (2009). "Life, DNA & h2g2: Douglas Adams's Biography" Accessed 9 July 2014

- ^ Internet Movie Database's page for Hyperland

- ^ Silverman, Dave (1998–1999). "Interview: Douglas Adams". American Atheist. 37 (1). Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bunce, Kim (5 November 2006). "Observer, ''The God Delusion'', 5 November 2006". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ Cavalieri, Paola and Peter Singer, editors (1994). The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity (U.S. Paperback ed.). St. Martin's Griffin. pp. 19–23. ISBN 0-312-11818-X.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Adams, Douglas. "Dongly things". douglasadams.com. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ OMTP: Common Charging and Local Data Connectivity (link), 11 February 2009

- ^ "The Ninth Douglas Adams Memorial Lecture". Save the Rhino International. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Douglas Adams The Party". Save the Rhino International. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Douglas Adams Memorial Lecture 2013". Save the Rhino International. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- ^ "Douglas Adams Memorial Lecture 2014". Save the Rhino International. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ^ a b Simpson 2003, pp. 184–185

- ^ Adams, Douglas and Mark Carwardine (1991). Last Chance to See (First U.S. Hardcover ed.). Harmony Books. p. 59. ISBN 0-517-58215-5.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (2002). The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time (First UK hardcover edition ed.). Macmillan. pp. 90–1. ISBN 0-333-76657-1.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "Craig Ferguson 23 February, 2010B Late Late show Stephen Fry PT2". YouTube. 21 June 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Adams's final post on his forums at". Douglasadams.com. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ "Discussions – alt.fan.douglas-adams | Google Groups". Google. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ Adams, Douglas (15 May 2001). "PDC 1996 Keynote with Douglas Adams". channel9.msdn.com. Channel 9. Retrieved 22 March 2013.

- ^ Cassel, David (15 May 2001). "So long, Douglas Adams, and thanks for all the fun". Salon. Salon Media Group. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d "Islington People's Plaques". 25 July 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Bowers, Keith (6 July 2011). "Big Three". SF Weekly. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Webb, Chapter 10.

- ^ "Obituary & Guest Book Preview for Jane Elizabeth BELSON". The Times. 9 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jane Belson, Douglas Adams's widow, passed away". h2g2. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ Lewis, Judith; Shulman, Dave (24 May 2001). "Lots of Screamingly Funny Sentences. No Fish. – page 1". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on 24 May 2001. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Simpson 2003, pp. 337–338

- ^ Gaiman, 204.

- ^ "BBC Online – Cult – Hitchhiker's – Douglas Adams – Service of Celebration". BBC. 17 September 2001. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Parrots, the universe and everything, recorded May 2001". YouTube. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Transcript of "Parrots, the Universe and Everything"". Navarroj.com. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ Asteroid named after 'Hitchhiker' humorist: Late British sci-fi author honored after cosmic campaign by Alan Boyle, MSNBC, 25 January 2005

- ^ Murray, Charles Shaar (10 May 2002). "The Salmon of Doubt by Douglas Adams". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

- ^

"Cover Stories: Douglas Adams, Narnia Chronicles, Something like a House". The Independent. London. 5 January 2002. Retrieved 2 August 2009.

{{cite news}}:|first=missing|last=(help) - ^ "Dirk Maggs News and New Projects page". Archived from the original on 9 February 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 27 April 2008 suggested (help) - ^ Matthew Hemley (5 May 2009). "The Stage / News / Douglas Adams's final Dirk Gently novel to be adapted for Radio 4". The Stage. Retrieved 20 August 2009.

- ^ "BBC plans Dirk Gently TV series". Chortle.co.uk. 11 October 2009. Retrieved 11 October 2009.

- ^ "Don't Panic! Google Doodle Honors Author Douglas Adams". abc News. 11 March 2013. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ "Douglas Adams' 61st Birthday". Retrieved 11 March 2013.

References

- Adams, Douglas (1998). Is there an Artificial God?, speech at Digital Biota 2, Cambridge, England, September 1998.

- Adams, Douglas (2002). The Salmon of Doubt: Hitchhiking the Galaxy One Last Time. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-76657-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dawkins, Richard (2003). "Eulogy for Douglas Adams," in A devil's chaplain: reflections on hope, lies, science, and love. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Felch, Laura (2004). Don't Panic: Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy by Neil Gaiman, May 2004

- Ray, Mohit K (2007). Atlantic Companion to Literature in English, Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. ISBN 81-269-0832-7

- Simpson, M. J. (2003). Hitchhiker: A Biography of Douglas Adams (1st ed.). Boston, Mass.: Justin, Charles & Co. ISBN 1-932112-17-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Webb, Nick (2005a). Wish You Were Here: The Official Biography of Douglas Adams. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-47650-6

- Webb, Nick (2005b). "Adams, Douglas Noël (1952–2001)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, January 2005. Retrieved 25 October 2005.

Further reading

- Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, established by him, and still operated by The Digital Village

- Douglas Adams at TED

- Douglas Adams speech at Digital Biota 2 (1998) (The audio of the speech)

- Guardian Books "Author Page", with profile and links to further articles.

- Template:Worldcat id

- Douglas Adams & his Computer article about his Mac IIfx

- BBC2 "Omnibus" tribute to Adams, presented by Kirsty Wark, 4 August 2001

- Mueller, Rick and Greengrass, Joel (2002).Life, The Universe and Douglas Adams, documentary.

- Simpson, M.J. (2001). The Pocket Essential Hitchhiker's Guide. ISBN 1-903047-40-4. Updated April 2005 ISBN 1-904048-46-3

External links

Media related to Douglas Adams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Douglas Adams at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Douglas Adams at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Douglas Adams at Wikiquote- Douglas Adams at Find a Grave

- Douglas Adams at IMDb

- Towel Day, 25 May

- Douglas Adams

- 1952 births

- 2001 deaths

- Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge

- Animal rights advocates

- Atheism activists

- Audio book narrators

- BBC radio producers

- British child writers

- Burials at Highgate Cemetery

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- English atheists

- English comedy writers

- English humanists

- English humorists

- English novelists

- English radio writers

- English science fiction writers

- English television writers

- Infocom

- Interactive fiction writers

- Monty Python

- Non-fiction environmental writers

- People educated at Brentwood School (Essex)

- People from Cambridge

- Usenet people

- Critics of religions

- 20th-century British novelists

- 21st-century British novelists