Epitestosterone

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| ATC code |

|

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.169.813 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C19H28O2 |

| Molar mass | 288.42 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

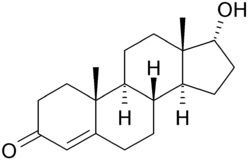

Epitestosterone is an endogenous antiandrogen[1] steroid, an epimer of the hormone testosterone. It is a weak competitive antagonist of the androgen receptor (AR) and a potent 5α-reductase inhibitor.[2]

Structurally, it differs from testosterone only in the configuration at the OH-bearing carbon, C17. Epitestosterone is believed to form in a similar way to testosterone; a 1993 study found that around 50% of epitestosterone production in human males can be ascribed to the testis,[3] although the exact pathway of its formation is still the subject of research. It has been shown to accumulate in mammary cyst fluid and in the prostate.[3] Epitestosterone levels are typically highest in young males; however, by adulthood, most healthy males exhibit a testosterone to epitestosterone ratio (T/E ratio) of about 1:1.[4]

Epitestosterone and testosterone

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (January 2009) |

This article contains weasel words: vague phrasing that often accompanies biased or unverifiable information. (November 2009) |

It has been shown that exogenous administration of testosterone does not affect levels of epitestosterone in the body. As a result, tests to determine the ratio of testosterone to epitestosterone in urine are used to find athletes who are doping.[5] A study of Australian athletes found that the mean T/E ratio in the study was 1.15:1.[6] Another study found that the max T/E ratio for the 95th percentile of athletes was 3.71:1, and the max T/E ratio for the 99th percentile was 5.25:1 [7]

Epitestosterone has not been shown to enhance athletic performance, although administration of epistestosterone can be used to mask a high level of testosterone if the standard T/E ratio test is used. As such, epitestosterone is banned by many sporting authorities as a masking agent for testosterone.

In 1996 the US athlete Mary Decker failed a T/E test with a T/E ratio of greater than 6, the limit in force at the time. She took the case to arbitration, arguing that birth control pills can cause false positives for the test, but the arbitration panel ruled against her.

On September 20, 2007 Floyd Landis was stripped of his title as winner of the Tour de France, and was subjected to a two-year ban from professional racing after a second test showing an elevated T/E ratio. Landis won the 17th stage of the tour; however, tests taken immediately after the stage victory showed a T/E ratio of 11:1, more than double the 4:1 imposed limit (recently lowered from prior limits of 8:1 and 6:1). On August 1, 2006, media reports said that synthetic testosterone had been detected in the A sample, using the carbon isotope ratio test CIR. The presence of synthetic testosterone means that some of the testosterone in Landis’s body came from an external source and was not naturally produced by his own system. These results conflict with Landis's public speculation that it was a natural occurrence.[8] Landis originally denied the charges, but in 2010 Landis admitted to doping during much of his career,[9] but continued to adamantly deny taking testosterone that would have led to the positive test in the 2006 Tour de France.[10]

Notes

- ^ P. Michael Conn (29 May 2013). Animal Models for the Study of Human Disease. Academic Press. pp. 376–. ISBN 978-0-12-415912-9.

- ^ Stárka L, Bicíková M, Hampl R (1989). "Epitestosterone--an endogenous antiandrogen?". J. Steroid Biochem. 33 (5): 1019–21. doi:10.1016/0022-4731(89)90255-0. PMID 2532272.

- ^ a b Dehennin L (February 1993). "Secretion by the human testis of epitestosterone, with its sulfoconjugate and precursor androgen 5-androstene-3 beta,17 α-diol". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 44 (2): 171–7. doi:10.1016/0960-0760(93)90025-R. PMID 8439521.

- ^ Bellemare V, Faucher F, Breton R, Luu-The V (2005). "Characterization of 17α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity (17α-HSD) and its involvement in the biosynthesis of epitestosterone". BMC Biochem. 6: 12. doi:10.1186/1471-2091-6-12. PMC 1185520. PMID 16018803.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Aguilera R, Hatton CK, Catlin DH (2002). "Detection of epitestosterone doping by isotope ratio mass spectrometry". Clin. Chem. 48 (4): 629–36. PMID 11901061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://doping-info.de/proceedings/proceedings_10_pdf/10_261.pdf

- ^ http://scienceblogs.com/purepedantry/upload/2006/07/te.jpg

- ^ "Synthetic testosterone found in Landis urine sample". Associated Press. 2006-07-31. Archived from the original on 2007-12-12. Retrieved 2007-09-25.

- ^ Albergotti, Reed (2010-05-20). "Cyclist Floyd Landis Admits Doping, Alleges Use by Armstrong and Others". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-05-20.

- ^ Bonnie D. Ford (2010-05-20). "Landis admits doping, accuses Lance". ESPN.

External links

- Landis has T/E ratio twice the tour limit

- Stárka L (October 2003). "Epitestosterone". J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 87 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00383-2. PMID 14630088.

- Sanders BK (2007). "Sex, drugs and sports: prostaglandins, epitestosterone and sexual development". Med. Hypotheses. 69 (4): 829–35. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.058. PMID 17382481.

- Loraine JA, Ismail AA, Adamopoulos DA, Dove GA (November 1970). "Endocrine Function in Male and Female Homosexuals". Br Med J. 4 (5732): 406–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.4.5732.406. PMC 1819981. PMID 5481520.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Griffiths PD, Merry J, Browning MC; et al. (December 1974). "Homosexual women: an endocrine and psychological study". J. Endocrinol. 63 (3): 549–56. doi:10.1677/joe.0.0630549. PMID 4452820.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)